Magical Realism and the Space Between Spaces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Postmodernist Narrative: in Search of an Altemative

Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingleses 12 (1999): 19-36 Postmodernist Narrative: In Search of an Altemative. Brian Crews Universidad de Sevilla ABSTRACT The development of the novel form is an exploration of the possibilities for realistic representation which is increasingly informed by an understanding that distortion and fabrication are inevitable consequences of the mediating process of narrative. The search for alternatives to conventional modes of representation as a way of defamiliarizing this state of affairs draws attention to the fact that the ordered human constructs that compose knowledge are fictitious systems that inevitably invade reality. A number of contemporary authors, through a variety of strategies emphasize the inevitable distortion involved in representation. The world is always transposed, reality is always framed in terms of the conventions we know and becomes an unfamiliar absence continually deferred by the fictitious construct we cali knowledge. Martin Amis, Angela Cárter and Ian McEwan are just a few of the authors who question existing realisms and posit alternatives but in the knowledge that reality is always other than what we make it. Postmodernism is really all about forms of representation and the ways in which we depict and come to terms with what we cali reality (no matter the médium involved); or even if we can talk about reality or truth at all. J.F. Lyotard suggests that all forms of representation rely upon narrative in order to validare themselves, and it could be said that all knowledge is primarily narrative as, no matter their médium, all artistic and cultural representations require some metanarrative to explain, validate or justify them (1984: 7). -

13Th FLOOR ELEVATORS

13th FLOOR ELEVATORS With such a seminal album, it’s not surprising that the cover for The Psychedelic Sounds Of The 13th Floor Elevators (1966 : International Artists Artwork : John Cleveland) has been borrowed such a lot, often by psych upstarts (also leaning on the music) and CD compliers wanting some of the early sixties garage ambience to rub off on them. The result is a great display of primary colours. Artist : The Suicidal Flowers Title : The Psychedevilic Sounds Of The Suicidal Flowers / 1997 Album / Suicidal Flowers Artwork : Unknown Artist : Artist : Various Various Artists Artists Title : The Title : The Pseudoteutonic Psychedelic Sounds Of The Sounds Of The Prae-Kraut Sonic Cathedral Pandaemonium # / 2010 14 / 2003 Album / Sonic Album / Lost Cathedral Continence Recordings Artwork / Artwork : Jimmy Reinhard Gehlen Young - Andrea Duwa - Splash 1 COVERED! PAGE 6 1 LEONA ANDERSON ASH RA TEMPEL Leona Anderson’s 1958 long-player Music To Suffer By (Unique Records) This copy of Ash Ra Tempel’s 1973 album is a gem, though I must admit I’ve never been able to get vinyl albums Starring Rosi lovingly recreates Peter to shatter quite like that (or the Buzzcocks TV show intro). The Makers Geitner’s original (cover photo : Claus have actually copied the original image for their EP and then just Kranz). added a new label design. Artist : Magic Aum Gigi Title : Starring Keiko/ 2000? Album / Fractal Records Artwork : Peter Artist : The Geitner (Photo : Makers Magic Aum Gigi) Title : Music To Suffer By / 1995 3 track EP / Estrus Wreckers Artwork : Art Chantry Artist : Smiff-N- Artist : Pavement Wessum Title : Watery, Title : Dah Shinin’ Domestic / 1992 / 1995 EP / Matador Album / Wreck Records Records Artwork : Unknown Artwork : C.M.O.N. -

The Success and Ambiguity of Young Adult Literature: Merging Literary Modes in Contemporary British Fiction Virginie Douglas

The Success and Ambiguity of Young Adult Literature: Merging Literary Modes in Contemporary British Fiction Virginie Douglas To cite this version: Virginie Douglas. The Success and Ambiguity of Young Adult Literature: Merging Literary Modes in Contemporary British Fiction. Publije, Le Mans Université, 2018. hal-02059857 HAL Id: hal-02059857 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02059857 Submitted on 7 Mar 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Abstract: This paper focuses on novels addressed to that category of older teenagers called “young adults”, a particularly successful category that is traditionally regarded as a subpart of children’s literature and yet terminologically insists on overriding the adult/child divide by blurring the frontier between adulthood and childhood and focusing on the transition from one state to the other. In Britain, YA fiction has developed extensively in the last four decades and I wish to concentrate on what this literary emergence and evolution has entailed since the beginning of the 21st century, especially from the point of view of genre and narrative mode. I will examine the cases of recognized—although sometimes controversial—authors, arguing that although British YA fiction is deeply indebted to and anchored in the pioneering American tradition, which proclaimed the end of the Romantic child as well as that of the compulsory happy ending of the children’s book, there seems to be a recent trend which consists in alleviating the roughness, the straightforwardness of realism thanks to elements or touches of fantasy. -

The Epistemic Value of Speculative Fiction JOHAN DE SMEDT and HELEN DE CRUZ

bs_bs_banner MIDWEST STUDIES IN PHILOSOPHY Midwest Studies In Philosophy, XXXIX (2015) The Epistemic Value of Speculative Fiction JOHAN DE SMEDT and HELEN DE CRUZ 1. STORYTELLING AND PHILOSOPHIZING In Daniel F. Galouye’s novel Simulacron-3 (1964), a team of computer scientists employs an elaborate computer simulation to reduce the need for marketing research in the actual world.The agents in the simulation are conscious and do not realize they live in a simulated world. When Morton Lynch, one of the scientists, mysteriously disappears, his colleague Douglas Hall attempts to find out what happened to him, only to realize that nobody else even remembers the vanished man. Gradually, it transpires that the world Hall inhabits is also a simulation, and thus that their creation is a simulation within a simulation. The fact that Hall remembers Lynch is a computer glitch. The novel explores several philosophical topics: If the creator of a simulated world turns out to be a malicious sadist (as is the case in the novel), can he be considered a god to his creation? Do simulated beings have souls? If there is an afterlife, will only “real” people go there, or also simulated beings? Can you fall in love with a simulated being? How do people from the level above know they are living in the real physical world, or do they perhaps also inhabit a simulation? Schwitzgebel and Bakker (2013) explore similar issues in their short story Reinstalling Eden, focusing on the moral responsibilities of creators of simulations to their simulated entities. Nick Bostrom (2003), in his philosophical paper “Are We Living in a Com- puter Simulation?,” uses a weak indifference principle and probability calculus to argue that it is either highly likely that we are living in a computer simulation, or that future generations will never run any simulations (for instance, because they © 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. -

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

Monsters and Near-Death Experiences in Eric Mccormack's First Blast Of

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0374-y OPEN Monsters and near-death experiences in Eric McCormack’s First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women Martin Kuester1* ABSTRACT Following Linda Hutcheon’sdefinition of parody as “repetition with a differ- ence”, this essay exposes how a contemporary Canadian novel parodically responds to 1234567890():,; seminal Early Modern English pre-texts. Eric McCormack is not only a Canadian post- modernist (and postcolonial) writer born in Scotland but also a specialist in Early Modern English literature and thus an ideal representative of the intertextual situation of Canadian writing between literary tradition and the challenges of postmodern/postcolonial writing. The essay interprets McCormack’s sexual gothic novel First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women discussing the way in which a literal or even literalist—rather than metaphorical—interpretation of literary and religious texts of the Early Modern period can make an important and sometimes harrowing difference in the lives of somewhat unsophisticated literary characters. McCormack’s ominously named character Andrew Halfnight literally interprets religious and literary texts he sees as signposts and guidelines of his personal behavior, thus showing how a literal interpretation of “canonical” texts limits the character’s ability to lead a self-determined happy life. The texts he refers to include the pamphlet The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women by Scottish reformer John Knox, Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy and John Milton’s Paradise Lost, and these subtexts are more than challenged through their intertextual transfer into erotic or perhaps even pornographic contexts which probably would have shocked the Early Modern authors (although, for example, Milton was at least not unwilling or unable to include ero- ticism in his work). -

An Original Album} an Honors Thesis (HONR 499} by Grant

The College Experience (An Original Album} An Honors Thesis (HONR 499} by Grant Armstrong Thesis Advisor Dr. Laurie Lindberg Ball State University Muncie, Indiana April2018 Expected Date of Graduation May 2018 Abstract Music has always been a way for people to express feelings and experiences. College is a major part of many people's lives, and everyone has a different experience. There are many situations, however, that a lot of college students experience. I created an album titled "The College Experience," consisting of three songs which I feel highlight some of the struggles and landmarks of college. The songs are "Undeclared," "Leftovers," and "What Have You Learned?" Each one describes a college student through a different experience in college. Acknowledgments I would like to thank Dr. Laurie Lindberg for advising me through this project. She provided much needed encouragement during times when I felt my songs weren't very good, and she kept me on track to help me finish on time. SrC-o/1 Under3rc,d The~.,.::-_, LD d. '-/(j;~ . Ll/ :J.-.0/lf' Process Analysis . r17G I first became interested in music when I was in middle school. The first instrument I learned to play was the drums. I took lessons for a few years and even played in my church's worship band for a while. Around this time, I began to play around on the piano, and I liked listening to songs and then figuring out how to play them. I even started writing original songs . The first song I ever wrote was for my brother when he went off to college. -

THE HANDBOOK Your South Beach Success Starts Here!

THE HANDBOOK Your South Beach Success Starts Here! Instructions, food lists, recipes and exercises to lose weight and get into your best shape ever CONTENTS HOW TO USE THIS HANDBOOK You’ve already taken the biggest step: committing to losing weight and learning to live a life of strength, energy PHASE 1 and optimal health. The South Beach Diet will get you there, and this handbook will show you the way. The 14-Day Body Reboot ....................... 4 The goal of the South Beach Diet® program is to help Diet Details .................................................................6 you lose weight, build a strong and fit body, and learn to Foods to Enjoy .......................................................... 10 live a life of optimal health without hunger or deprivation. Consider this handbook your personal instruction manual. EXERCISE: It’s divided into the three phases of the South Beach Beginner Shape-Up: The Walking Workouts ......... 16 Diet® program, color-coded so it’ll be easy to locate your Walking Interval Workout I .................................... 19 current phase: Walking Interval Workout II .................................. 20 PHASE 1 PHASE 2 PHASE 3 10-Minute Stair-Climbing Interval ...........................21 What you’ll find inside: PHASE 2 • Each section provides instructions on how to eat for that specific phase so you’ll always feel confident that Steady Weight Loss ................................. 22 you’re following the program properly. Diet Details .............................................................. 24 • Phases 1 and 2 detail which foods to avoid and provide Foods to Enjoy ......................................................... 26 suggestions for healthy snacks between meals. South Beach Diet® Recipes ....................................... 31 • Phase 2 lists those foods you may add back into your diet and includes delicious recipes you can try on EXERCISE: your own that follow the healthy-eating principles Beginner Body-Weight Strength Circuit .............. -

The Happy Ending – Will It Happen to Me Too? Mako Nagasawa Last Modified: October 2, 2007 for BCACF

The Happy Ending – Will It Happen to Me Too? Mako Nagasawa Last modified: October 2, 2007 for BCACF Introduction: What Story Do You Live In? This morning I want to ask you, ‘What story do you live in?’ All of us live in a story. We have a storyline running through our heads. And we play a major role in it. Let me give you some examples. Do you live in the hero story? This is a story where someone who makes a difference in the world and makes a name for himself or herself. You start off with some kind of hidden talent. You face obstacles, adversity, mountains and valleys of hard work, only to overcome in the end. What matters is the quest, the challenge, and the victory. It is the story of Harry Potter, the unlikely hero who is given a burden that no one else could carry, who fulfills his destiny. It is the story of King Leonidas, who gives his life against King Xerxes and the Persian Empire. Here’s a clip from 300 on that. [clip from Scene 17, where Xerxes is calling Leonidas to submit to him.] Notice how the threat of Xerxes is to wipe out Leonidas’ story. But as we know, the story is being retold by Dilios, who finishes his story on a new battlefield. As he finishes his story of the 300, he says, ‘Here they stare now, across the plain, at 10,000 Spartans, commanding 30,000 free Greeks,’ who are now united behind Sparta. Did you know that that story was retold in World War II. -

Genre and Subgenre

Genre and Subgenre Categories of Writing Genre = Category All writing falls into a category or genre. We will use 5 main genres and 15 subgenres. Fiction Drama Nonfiction Folklore Poetry Realistic Comedy Informational Fiction Writing Fairy Tale Tragedy Historical Persuasive Legend Fiction Writing Tall Tale Science Biography Fiction Myth Fantasy Autobiography Fable 5 Main Genres 1. Nonfiction: writing that is true 2. Fiction: imaginative or made up writing 3. Folklore: stories once passed down orally 4. Drama: a play or script 5. Poetry: writing concerned with the beauty of language Nonfiction Subgenres • Persuasive Writing: tries to influence the reader • Informational Writing: explains something • Autobiography: life story written by oneself • Biography: Writing about someone else’s life Latin Roots Auto = Self Bio = Life Graphy = Writing Fiction Subgenres • Historical Fiction: set in the past and based on real people and/or events • Science Fiction: has aliens, robots, futuristic technology and/or space ships • Realistic Fiction: has no elements of fantasy; could be true but isn’t • Fantasy: has monsters, magic, or characters with superpowers Folklore Subgenres Folklore/Folktales usually has an “unknown” author or will be “retold” or “adapted” by the author. • Fable: short story with personified animals and a moral Personified: given the traits of people Moral: lesson or message of a fable • Myth: has gods/goddesses and usually accounts for the creation of something Folklore Subgenres (continued) Tall Tale • Set in the Wild West, the American frontier • Main characters skills/size/strength is greatly exaggerated • Exaggeration is humorous Legend • Based on a real person or place • Facts are stretched beyond nonfiction • Exaggerated in a serious way Folklore Subgenres (continued) Fairytale: has magic and/or talking animals. -

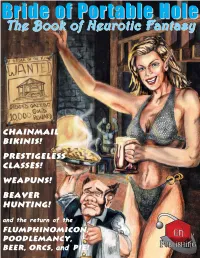

Bride of Portable Hole: the Book of Neurotic Fantasy

BrideBride ofof PorPortabletable HoleHole TThhee BBooookk ooff NNeeuurroottiicc FFaannttaassyy ChainmailChainmail Bikinis!Bikinis! PrestigelessPrestigeless Classes!Classes! WeaPuns!WeaPuns! BeaverBeaver hunting!hunting! and the return of the Flumphinomicon,Flumphinomicon, Poodlemancy,Poodlemancy, BEER,BEER, Orcs,Orcs, andand PIE!PIE! this page intentionally left blank TheThe BookBook ofof NeuroticNeurotic FantasyFantasy CREDITS TABLE OF CONTENTS Written by M Jason Parent & Denise Robinson with d200 Result Chad Barr, Arthur Borko, Leonard “Half-Mad” Briden, Cameron “Fitz” Burns, Matt B Carter, Mike Chapin, Michael 00 Cover Dallaire, Mike “Ralts” Downs, Danny S Dyche, Horacio 01 Credits & Table of Contents Gonzales, Gareth Hanrahan, Brannon Hollingsworth, Neal 02-003 Introductions Levin, Peter Lustig, Joe Mucchiello, Shawn “Zanatose” 04-005 Eric and the Dread Gazebo Muder, Ryan Nock, Hong Ooi, M Jason Parent, Darren 06-442 Prestigeless Classes Pearce, Stefan Pietraszak, Charles Plemons III, Johnathan M. 44-552 Feats Richards, Chris Richardson, Chrystine Robinson, Geneviève 54-778 Encounters Robinson, W. Shade, John Henry Stam, Samuel Terry, Beau 54-60 Return to the Orc & the Pastry Yarbrough, Zjelani 61-66 Revenge of the Orc & the Pastry 67-68 Lost Penguin Colony 69-71 Himover, Poodlemancer 72-75 Elemental Plane of Candy Illustrations by 76-77 Deus Ex Machina Tony ìSquidheadî Monorchio 78-1101 Monsters 78-85 Flumphonomicon with 86-94 Monsters of the Metagame Matthew Cuenca, Johnathan Fuller, J.L.Jones, Kayvan Koie, 95-101 Templates Frank -

Campus Press April May 2018 Online Edition

C_ P7 C773: “Striving to Report the News Accurately, Fairly and Fully” TheTheThe Campus Press Student Newspaper of Camden County College www.camdencc.edu Volume 32, Issue 3 April/May 2018 COMMENCEMENT DAY How to Conquer the Real World and Look Sharp While Doing It! Friday, May 11, 2018 B1 KJYJ M-G77 slacks, a blouse or sweater, and an optional 10 a.m. Campus Press Co-Editor and News Reporter blazer. For men, business casual attire is dress slacks or trousers, a collared shirt or dress shirt Truman Courtyard oining the workforce may seem daunting, with or without a tie, dark socks, and dress but while you may feel nervous on the Blackwood Campus shoes. J inside, a professional wardrobe is the key to looking more confident than you feel. Men: Keep a Jacket and Tie Handy BYY7J`...BYY7J` According to Allison Green, a Professor and Ladies: Blazer and Heels are Must Wear the Coordinator of Speech at Camden County This all may seem like a lot, but after College, and our resident fashionista, “What you speaking with Green, it’s not as difficult as it May 1: 2018-2019 Financial Aid Priority choose to wear is an expression of respect not Filing Deadline seems. According only for the job, but to Green, men May 9: Final Exams Begin for yourself.” DRESSING TO IMPRESS AND FOR SUCCESS should keep a May 11: Commencement Day With what you ADVICE COLUMN: Timely Advice to jacket and a tie wear portraying who Graduates and Those Planning for in their backseat you are, it is for emergencies.