Archaeolingua

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Act Cciii of 2011 on the Elections of Members Of

Strasbourg, 15 March 2012 CDL-REF(2012)003 Opinion No. 662 / 2012 Engl. only EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) ACT CCIII OF 2011 ON THE ELECTIONS OF MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT OF HUNGARY This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int CDL-REF(2012)003 - 2 - The Parliament - relying on Hungary’s legislative traditions based on popular representation; - guaranteeing that in Hungary the source of public power shall be the people, which shall pri- marily exercise its power through its elected representatives in elections which shall ensure the free expression of the will of voters; - ensuring the right of voters to universal and equal suffrage as well as to direct and secret bal- lot; - considering that political parties shall contribute to creating and expressing the will of the peo- ple; - recognising that the nationalities living in Hungary shall be constituent parts of the State and shall have the right ensured by the Fundamental Law to take part in the work of Parliament; - guaranteeing furthermore that Hungarian citizens living beyond the borders of Hungary shall be a part of the political community; in order to enforce the Fundamental Law, pursuant to Article XXIII, Subsections (1), (4) and (6), and to Article 2, Subsections (1) and (2) of the Fundamental Law, hereby passes the following Act on the substantive rules for the elections of Hungary’s Members of Parliament: 1. Interpretive provisions Section 1 For the purposes of this Act: Residence: the residence defined by the Act on the Registration of the Personal Data and Resi- dence of Citizens; in the case of citizens without residence, their current addresses. -

Original File Was Neolithicadmixture4.Tex

Supplementary Information: Parallel ancient genomic transects reveal complex population history of early European farmers Table of Contents Supplementary note 1: Archaeological summary of the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods in the region of today’s Hungary………………………………………………………………………....2 Supplementary note 2: Description of archaeological sites………………………………………..8 Supplementary note 3: Y chromosomal data……………………………………………………...45 Supplementary note 4: Neolithic Anatolians as a surrogate for first European farmers..………...65 Supplementary note 5: WHG genetic structure and admixture……………………………….......68 Supplementary note 6: f-statistics and admixture graphs………………………………………....72 Supplementary note 7: ALDER.....……..…………………………………………………...........79 Supplementary note 8: Simulations……………………………………………….…...................83 1 Supplementary note 1: Archaeological summary of the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods in the region of today’s Hungary The Carpathian Basin (including the reagion of today’s Hungary) played a prominent role in all prehistoric periods: it was the core territory of one cultural complex and, at the same time, the periphery of another, and it also acted as a mediating or contact zone. The archaeological record thus preserves evidence of contacts with diverse regions, whose vestiges can be found on settlements and in the cemeteries (grave inventories) as well. The earliest farmers arrived in the Carpathian Basin from southeastern Europe ca. 6000–5800 BCE and they culturally belonged to the Körös-Çris (east) and Starčevo (west) archaeological formations [1, 2, 3, 4]. They probably encountered some hunter-gatherer groups in the Carpathian Basin, whose archaeological traces are still scarce [5], and bioarchaeological remains are almost unknown from Hungary. The farmer communities east (Alföld) and west (Transdanubia) of the Danube River developed in parallel, giving rise around 5600/5400 BCE to a number of cultural groups of the Linearband Ceramic (LBK) culture [6, 7, 8]. -

Editors RICHARD FOSTER FLINT GORDON

editors EDWARD S RICHARD FOSTER FLINT GORDON EN, III ---IRKING ROUSE YALE U IVE, R T ' HAVEN, _ONNEC. ICUT RADIOCARBON Editors: EDWARD S. DEEVEY-RICHARD FOSTER FLINT-J. GORDON OG1 EN, III-IRVING ROUSE Managing Editor: RENEE S. KRA Published by THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SCIENCE Editors: JOHN RODGERS AND JOHN H. OSTROI7 Published semi-annually, in Winter and Summer, at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. Subscription rate $30.00 (for institutions), $20.00 (for individuals), available only by volume. All correspondence and manuscripts should be addressed to the Managing Editor, RADIOCARBON, Box 2161, Yale Station, New Haven, Connecticut 06520. INSTRUCTIONS TO CONTRIBUTORS Manuscripts of radiocarbon papers should follow the recommendations in Sugges- tions to Authors, 5th ed. All copy must be typewritten in double space (including the bibliography): manuscripts for vol. 13, no. 1 must be submitted in duplicate by February 1, 1971, and for vol. 13, no. 2 by August 1, 1971. Description of samples, in date lists, should follow as closely as possible the style shown in this volume. Each separate entry (date or series) in a date list should be considered an abstract, prepared in such a way that descriptive material is distinguished from geologic or archaeologic interpretation, but description and interpretation must be both brief and informative. Date lists should therefore not be preceded by abstracts, but abstracts of the more usual form should accompany all papers (e.g. geochemical contributions) that are directed to specific problems. Each description should include the following data, if possible in the order given: 1. Laboratory number, descriptive name (ordinarily that of the locality of collec- tion), and the date expressed in years B.P. -

From Early Trade and Communication Networks to the Internet, the Internet of Things and the Global Intelligent Machine (GIM)

Advances in Historical Studies, 2019, 8, 1-23 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ahs ISSN Online: 2327-0446 ISSN Print: 2327-0438 From Early Trade and Communication Networks to the Internet, the Internet of Things and the Global Intelligent Machine (GIM) Teun Koetsier Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Science, VU University, Amsterdam, The Netherlands How to cite this paper: Koetsier, T. Abstract (2019). From Early Trade and Communi- cation Networks to the Internet, the Inter- The present paper offers a sketch of the history of networks from the Stone net of Things and the Global Intelligent Age until the present. I argue that man is a creator of networks, a homo reti- Machine (GIM). Advances in Historical culorum. Over the course of time more and more networks were created and Studies, 8, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.4236/cm.2019.81001 they have become increasingly technologized. It seems inevitable that they will all be incorporated in the successor of the Internet of Things, the Global Received: December 21, 2018 Intelligent Machine (GIM). Accepted: January 29, 2019 Published: February 1, 2019 Keywords Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and History of Networks, Global Intelligent Machine Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0). 1. Introduction http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Open Access Although we nowadays also use the word tool in a more general sense, tools and machines are traditionally physical devices invented to perform a task. They have a material existence and they operate on the basis of the laws of physics. -

Chapter 8 Glossary

Technology: Engineering Our World © 2012 Chapter 8: Machines—Glossary friction. A force that acts like a brake on moving objects. gear. A rotating wheel-like object with teeth around its rim used to transmit force to other gears with matching teeth. hydraulics. The study and technology of the characteristics of liquids at rest and in motion. inclined plane. A simple machine in the form of a sloping surface or ramp, used to move a load from one level to another. lever. A simple machine that consists of a bar and fulcrum (pivot point). Levers are used to increase force or decrease the effort needed to move a load. linkage. A system of levers used to transmit motion. lubrication. The application of a smooth or slippery substance between two objects to reduce friction. machine. A device that does some kind of work by changing or transmitting energy. mechanical advantage. In a simple machine, the ability to move a large resistance by applying a small effort. mechanism. A way of changing one kind of effort into another kind of effort. moment. The turning force acting on a lever; effort times the distance of the effort from the fulcrum. pneumatics. The study and technology of the characteristics of gases. power. The rate at which work is done or the rate at which energy is converted from one form to another or transferred from one place to another. pressure. The effort applied to a given area; effort divided by area. pulley. A simple machine in the form of a wheel with a groove around its rim to accept a rope, chain, or belt; it is used to lift heavy objects. -

Editor Associate Editors

VOLUME 29 / NUMBER 1 / 1987 Published by THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SCIENCE Editor MINZE STUIVER Associate Editors To serve until January 1, 1989 STEPHEN C PORTER Seattle, Washington To serve until January 1, 1988 W G MOOK Groningen, The Netherlands HANS OESCHGER Bern, Switzerland To serve until January 1, 1990 ANDREW MOORE New Haven, Connecticut To serve until January 1, 1992 CALVIN J HEUSSER Tuxedo, New York Managing Editor RENEE S KRA Kline Geology Laboratory Yale University New Haven, Connecticut 06511 ISSN: 0033-8222 NOTICE TO READERS AND CONTRIBUTORS Since its inception, the basic purpose of RADIOCARBON has been the publication of compilations of 14C dates produced by various laboratories. These lists are extremely useful for the dissemination of basic 14C information. In recent years, RADIOCARBON has also been publishing technical and interpretative articles on all aspects of 14C. We would like to encourage this type of publication on a regular basis. In addition, we will be publishing compilations of published and unpublished dates along with interpretative text for these dates on a regional basis. Authors who would like to compose such an article for his/her area of interest should contact the Managing Editor for infor- mation. Another section is added to our regular issues, "Notes and Comments." Authors are invited to extend discussions or raise pertinent questions to the results of scientific inves- tigations that have appeared on our pages. The section includes short, technical notes to relay information concerning innovative sample preparation procedures. Laboratories may also seek assistance in technical aspects of radiocarbon dating. Book reviews will also be included for special editions. -

Historical Development of the Wheel

HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE WHEEL Next to controlled fire, the wheel was clearly early man’s most significant invention. It advanced transportation, manufacturing, and warfare significantly and to this day is present in multiple forms from rotary tools, electric generators, trains, automobiles and jet engines to cooling fans in electronic computers and drills used in dentistry. We want here to speculate on how the wheel and all its later refinements were probably invented. It is likely that there were multiple sources for this invention driven by local needs. Certainly pottery wheels and war chariots were in use in ancient Mesopotamia by 3000BC and pictures of wagons found on pottery in eastern Europe, dated via carbon dating , also indicate the early use of wheels in wagons at about the same time. It is our contention that the concept of the wheel predate these times by thousands of years. Here are our thoughts on the matter. Early man clearly would have been aware of the circular shape of the sun and the moon and the periodicity involved in the movement of celestial objects. Certainly Cro-Magnon man some twenty thousand years ago would also have noticed that certain spherically shaped rocks found along beaches have the interesting characteristic that they roll down inclines. Soon someone would have made a toy using such rocks by inserting an axle into the center of several of such stones. Before long someone else would have come along and recognized that such rolling toys would work even better by replacing the drilled spherical pebbles with round stone or wooden discs in the shape suggested by the full moon and sun as they appeared in the sky. -

For Creative Minds

For Creative Minds The For Creative Minds educational section may be photocopied or printed from our website by the owner of this book for educational, non-commercial uses. Cross-curricular teaching activities, interactive quizzes, and more are available online. Go to www.ArbordalePublishing.com and click on the book’s cover to explore all the links. Simple Machines Simple machines have been used for hundreds of years. There are six simple machines—the wedge, wheel and axle, lever, inclined plane, screw, and pulley. They have few or no moving parts and they make work easier. When you use simple machines, you use a force—a push or a pull—to make something move over a distance. There are six types of simple machines. Use the color coding to match the machine’s description to its picture. A lever is a stiff bar that turns on a fixed point called a fulcrum. When one side of the lever is pushed down, the other side of the lever lifts up. A lever helps to lift or move things. An inclined plane is a slanted surface that connects a lower level to a higher level. Objects can be pushed or pulled along the inclined plane to move them from a high place to a low place, or a low place to a high place. A pulley has a grooved wheel and rope to raise and lower a load. Pulling on the rope causes the wheel to turn and raise the object on the other end of the rope. A screw has an inclined plane (a thread) wrapped around a shaft. -

Drávától a Balatonig a Dél-Dunántúli Vízügyi Igazgatóság Időszaki Lapja

DRÁVÁTÓL A BALATONIG a Dél-Dunántúli Vízügyi igazgatóság iDőszaki lapja 2020 | II. A tartalomból: kitüntetettjeink nemzeti ünnepünk, március 15. és a Víz Világnapja alkalmából tározási lehetőségek vizsgálata a Völgységi-patak vízgyűjtőjén a beruházás tapasztalatai az Ordacsehi szivattyútelep felújításáról 2. a tetves-patak fejlesztése a pécs, Edison úti kármentesítés múltja, jelene és jövője a Dráva – Fotó: szappanos Ferenc Tartalom KÖSZÖNTŐ BEncs zoltán Előszó 3 HÍREK jusztingEr Brigitta Kitüntetések a Víz Világnapja alkalmából 4 jusztingEr Brigitta Vezetőink elismerése Nemzeti Ünnepünk, március 15. és a Víz Világnapja alkalmából 5 jusztingEr Brigitta Online szakmai előadások a Víz Világnapja alkalmából – 2020. március 25. 6 HORVÁTH gábor Megkezdődött a duzzasztás a Cún-Szaporca holtág-rendszeren 7 jusztingEr Brigitta A MI VÍZÜGYÜNK 8 jusztingEr Brigitta A Föld napja – Április 22. 9 klEin judit Országos Szakmai Tanulmányi Verseny döntője 11 VÍZTUDOMÁNY FOnóD andrás Tározási lehetőségek vizsgálata a Völgységi-patak vízgyűjtőjén 12 VÍZ-ÜGYÜNK HORVÁTH gábor, pál irina, jakaB róbert, kulcsár lászló Első negyedéves hidrometeorológiai tájékoztató – 2020. január-március 17 ErB zsolt A beruházás tapasztalatai az Ordacsehi szivattyútelep felújításáról – II. rész 25 juhász zoltán A Tetves-patak védképességének javítása 29 GAÁL Erzsébet A Pécs, Edison úti kármentesítés múltja, jelene és jövője 31 HATÁRAINKON TÚL jusztingEr Brigitta A Trianoni békeszerződés vízügyes vonatkozásai 33 VÍZ-TÜKÖR jusztingEr Brigitta Interjú Sindler Csabával 36 EGY KIS -

Launch It! Lesson Overview Suggested Grade Levels

Launch It! Lesson Overview Students will investigate simple and compound machines. Suggested Grade Levels: 3-8 Standards for Lesson Content Standard A: Science as Inquiry Content Standard B: Physical Science VA SOL: 3.1 a, b, c; 3.2 a, b, c, d; 4.1 a, b; 5.1 e, f, h; 6.1 a, b, f, g, h, i; LS.1 a, b, e, f, i; PS.1 a, g, k, l, m; PS.10 d Time Needed This lesson can be completed in one class period. Materials for Lesson • 1-2 bags of jumbo marshmallows • Various objects that could be used as a lever such as ruler, plastic spoons, meter stick, paint stick, CD case • Small buckets or boxes to be used as a target for the marshmallows. Content Background Information for teacher: The simple machine lessens the effort needed to do the same amount of work, making it appear to be easier. The payoff is that we may have to exert less force over a greater distance. There are six basic or simple machines, which alone or in combination make up most of the machines and mechanical devices we use. These simple machines are the lever, the pulley, the wheel and axle, the incline, the wedge, and the screw. Compound machines are used to make work easier. A compound machine is made up of more than one type of simple machine. Common examples include scissors, shovel, wheelbarrow, pencil sharpener, and can opener. Simple and compound machines help us with our daily lives. Many of them are located at school, at home, and in our means of transportation. -

Rendelete Ordacsehi Község Helyi Hulladékgazdálkodási Tervéről

ORDACSEHI KÖZSÉG ÖNKORMÁNYZATÁNAK 19/2009. (IX. 21.) rendelete Ordacsehi község helyi hulladékgazdálkodási tervér ıl Kihirdetett szöveg A Képvisel ı-testület a hulladékgazdálkodásról szóló 2000. évi XLIII. törvény 35. §-ában kapott felhatalma- zás alapján - tekintettel a bels ı piaci szolgáltatásokról szóló, az Európai Parlament és a Tanács 2006/123/EK. irányelvre - a következ ı rendeletet alkotja: 1. § E rendelet hatálya Ordacsehi Község Önkormányzat közigazgatási területére terjed ki. 2. § (1) Ordacsehi község 2008-2013. év tervezési id ıszakra szóló helyi hulladékgazdálkodási terve szervesen beépül a Fonyód Kistérség Többcélú Társulás 2008-2013. év tervezési id ıszakra szóló hulladékgazdálkodási tervébe. (2) A „Fonyód Kistérség Többcélú Társulás Hulladékgazdálkodási Terve 2008-2013. év” dokumentum e rendelet mellékletét képezi. 3. § (1) E rendelet 2009. október 1-jén lép hatályba. (2) E rendelet hatálybalépésével Ordacsehi Község Önkormányzatának a Dél-nyugat Balatoni Kistérségi Önkormányzati Területfejlesztési Társulás hulladékgazdálkodási és Ordacsehi Község helyi hulladékgazdál- kodási terve (2004-2008) – r ıl szóló 21/2004.(X. 05.) rendelete hatályát veszti. (3) E rendelet a bels ı piaci szolgáltatásokról szóló, az Európai Parlament és a Tanács 2006/123/EK. irányelvnek való megfelelést szolgálja. ______________________________ Kiss Miklós Feikusné Horváth Erzsébet polgármester jegyz ı Kihirdetve 2009. szeptember 21-én. Feikusné Horváth Erzsébet jegyz ı Melléklet a 19/2009. (IX. 21.) rendelethez 1 FONYÓD KISTÉRSÉG TÖBBCÉ- LÚ TÁRSULÁS -

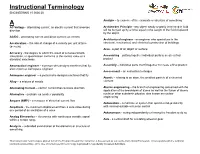

Instructional Terminology A

Instructional Terminology ENGINEERING 15.0000.00 Analyze – to examine of the elements or structure of something A AC Voltage - alternating current; an electric current that reverses Archimedes Principle - any object wholly or partly immersed in fluid direction will be buoyed up by a force equal to the weight of the fluid displaced by the object AC/DC - alternating current and direct current; an electric Architectural engineer - an engineer who specializes in the Acceleration – the rate of change of a velocity per unit of time structural, mechanical, and electrical construction of buildings (a=∆v/∆t) Area - a part of an object or surface Accuracy - the degree to which the result of a measurement, calculation, or specification conforms to the correct value or a Assembling – putting together individual parts to create a final standard; exactness product Aeronautical engineer – a person who designs machines that fly; Assembly – individual parts that fit together to create a final product also known as Aerospace engineer Assessment – an evaluation technique Aerospace engineer —a person who designs machines that fly Atomic – relating to an atom, the smallest particle of a chemical Alloy – a mixture of metals element Alternating Current – electric current that reverses direction Atomic engineering – the branch of engineering concerned with the application of the breakdown of atoms as well as the fusion of atomic Alternative - available as another possibility nuclei or other subatomic physics; also known as nuclear engineering Ampere (AMP) – a