Labor and Vaginal Delivery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preventing the First Cesarean Delivery

Current Commentary Preventing the First Cesarean Delivery Summary of a Joint Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Society for Maternal- Fetal Medicine, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Workshop Catherine Y. Spong, MD, Vincenzo Berghella, MD, Katharine D. Wenstrom, MD, Brian M. Mercer, MD, and George R. Saade, MD points were identified to assist with reduction in cesar- With more than one third of pregnancies in the United ean delivery rates including that labor induction should States being delivered by cesarean and the growing be performed primarily for medical indication; if done knowledge of morbidities associated with repeat cesar- for nonmedical indications, the gestational age should be ean deliveries, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Insti- at least 39 weeks or more and the cervix should be favor- tute of Child Health and Human Development, the able, especially in the nulliparous patient. Review of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and the American current literature demonstrates the importance of adher- College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists convened ing to appropriate definitions for failed induction and a workshop to address the concept of preventing the first arrest of labor progress. The diagnosis of “failed induc- cesarean delivery. The available information on maternal tion” should only be made after an adequate attempt. and fetal factors, labor management and induction, and Adequate time for normal latent and active phases of nonmedical factors leading to the first cesarean delivery the first stage, and for the second stage, should be was reviewed as well as the implications of the first allowed as long as the maternal and fetal conditions per- cesarean delivery on future reproductive health. -

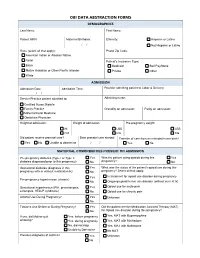

2020 CDA Paper Abstraction Forms

2020 OBI DATA ABSTRACTION FORMS DEMOGRAPHICS Hospital Name: Patient Last Name: Patient First Name: Medical Record Number (MRN): Maternal Birthdate (MM/DD/YY): Postal Zip Hispanic Ethnicity: Code: Hispanic or Latino Not Hispanic or Latino Race (select all that apply): Unknown American Indian or Alaskan Native Asian Patient's Insurance Type: Black or African American Medicaid Self Pay/None Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander Private Other: __________ White Unknown LABOR MANAGEMENT: Admission L&D Admission Date: L&D Admission Time: Provider admitting patient to Labor & Delivery (Last Name, First Name): Service/Practice patient admitted to: Admitting Nurse (Last name, First name): Certified Nurse Midwife Family Practice / Family Medicine Gravidity on admission: Parity on admission: Maternal Fetal Medicine Obstetrics Physician Maternal Height at admission: Maternal Weight at admission: Pre-pregnancy Weight: IN LBS LBS CM K G KG Did the patient receive prenatal care? If yes, date prenatal care Transfer of care from an intended home birth? started: Yes No Unable to determine Yes No LABOR MANAGEMENT: Maternal Comorbidities Present On Admission Pre-pregnancy diabetes (Type I or Type II Yes Was the patient using opioids during this Yes diabetes diagnosed prior to this pregnancy) No pregnancy? No Gestational diabetes (diagnosis in this pregnancy Yes What was the status of the patient's opioid use during this with or without medication tx) No pregnancy? (select all that apply): In treatment for opioid use disorder during pregnancy Pre-pregnancy -

OBGYN-Study-Guide-1.Pdf

OBSTETRICS PREGNANCY Physiology of Pregnancy: • CO input increases 30-50% (max 20-24 weeks) (mostly due to increase in stroke volume) • SVR anD arterial bp Decreases (likely due to increase in progesterone) o decrease in systolic blood pressure of 5 to 10 mm Hg and in diastolic blood pressure of 10 to 15 mm Hg that nadirs at week 24. • Increase tiDal volume 30-40% and total lung capacity decrease by 5% due to diaphragm • IncreaseD reD blooD cell mass • GI: nausea – due to elevations in estrogen, progesterone, hCG (resolve by 14-16 weeks) • Stomach – prolonged gastric emptying times and decreased GE sphincter tone à reflux • Kidneys increase in size anD ureters dilate during pregnancy à increaseD pyelonephritis • GFR increases by 50% in early pregnancy anD is maintaineD, RAAS increases = increase alDosterone, but no increaseD soDium bc GFR is also increaseD • RBC volume increases by 20-30%, plasma volume increases by 50% à decreased crit (dilutional anemia) • Labor can cause WBC to rise over 20 million • Pregnancy = hypercoagulable state (increase in fibrinogen anD factors VII-X); clotting and bleeding times do not change • Pregnancy = hyperestrogenic state • hCG double 48 hours during early pregnancy and reach peak at 10-12 weeks, decline to reach stead stage after week 15 • placenta produces hCG which maintains corpus luteum in early pregnancy • corpus luteum produces progesterone which maintains enDometrium • increaseD prolactin during pregnancy • elevation in T3 and T4, slight Decrease in TSH early on, but overall euthyroiD state • linea nigra, perineum, anD face skin (melasma) changes • increase carpal tunnel (median nerve compression) • increased caloric need 300cal/day during pregnancy and 500 during breastfeeding • shoulD gain 20-30 lb • increaseD caloric requirements: protein, iron, folate, calcium, other vitamins anD minerals Testing: In a patient with irregular menstrual cycles or unknown date of last menstruation, the last Date of intercourse shoulD be useD as the marker for repeating a urine pregnancy test. -

Pretest Obstetrics and Gynecology

Obstetrics and Gynecology PreTestTM Self-Assessment and Review Notice Medicine is an ever-changing science. As new research and clinical experience broaden our knowledge, changes in treatment and drug therapy are required. The authors and the publisher of this work have checked with sources believed to be reliable in their efforts to provide information that is complete and generally in accord with the standards accepted at the time of publication. However, in view of the possibility of human error or changes in medical sciences, neither the authors nor the publisher nor any other party who has been involved in the preparation or publication of this work warrants that the information contained herein is in every respect accurate or complete, and they disclaim all responsibility for any errors or omissions or for the results obtained from use of the information contained in this work. Readers are encouraged to confirm the information contained herein with other sources. For example and in particular, readers are advised to check the prod- uct information sheet included in the package of each drug they plan to administer to be certain that the information contained in this work is accurate and that changes have not been made in the recommended dose or in the contraindications for administration. This recommendation is of particular importance in connection with new or infrequently used drugs. Obstetrics and Gynecology PreTestTM Self-Assessment and Review Twelfth Edition Karen M. Schneider, MD Associate Professor Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences University of Texas Houston Medical School Houston, Texas Stephen K. Patrick, MD Residency Program Director Obstetrics and Gynecology The Methodist Health System Dallas Dallas, Texas New York Chicago San Francisco Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi San Juan Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto Copyright © 2009 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. -

Obi Data Abstraction Forms Demographics

OBI DATA ABSTRACTION FORMS DEMOGRAPHICS Last Name: First Name: Patient MRN: Maternal Birthdate: Ethnicity: Hispanic or Latino / / Not Hispanic or Latino Race (select all that apply): Postal Zip Code: American Indian or Alaskan Native Asian Patient's Insurance Type: Black Medicaid Self Pay/None Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander Private Other White ADMISSION Admission Date: Admission Time: Provider admitting patient to Labor & Delivery: / / Service/Practice patient admitted to: Admitting nurse: Certified Nurse Midwife Family Practice Gravidity on admission: Parity on admission: Maternal Fetal Medicine Obstetrics Physician Height at admission: Weight at admission: Pre-pregnancy weight: IN LBS LBS CM KG KG Did patient receive prenatal care? Date prenatal care started: Transfer of care from an intended home birth? Yes No Unable to determine / / Yes No MATERNAL COMORBIDITIES PRESENT ON ADMISSION Pre-pregnancy diabetes (Type I or Type II Yes Was the patient using opioids during this Yes diabetes diagnosed prior to this pregnancy) No pregnancy? No Gestational diabetes (diagnosis in this Yes What was the status of the patient's opioid use during this pregnancy with or without medication tx) No pregnancy? Select all that apply: Yes In treatment for opioid use disorder during pregnancy Pre-pregnancy hypertension (chronic) No Ongoing opioid/heroin use disorder (without current tx) Gestational hypertension (PIH, preeclampsia, Yes Opioid use for acute pain eclampsia, HELLP syndrome) No Opioid use for chronic pain Alcohol Use During Pregnancy? -

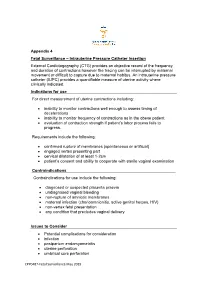

Intrauterine Pressure Catheter Insertion External Cardiotogography

Appendix 4 Fetal Surveillance – Intrauterine Pressure Catheter Insertion External Cardiotogography (CTG) provides an objective record of the frequency and duration of contractions however the tracing can be interrupted by maternal movement or difficult to capture due to maternal habitus. An intrauterine pressure catheter (IUPC) provides a quantifiable measure of uterine activity where clinically indicated. Indications for use For direct measurement of uterine contractions including: inability to monitor contractions well enough to assess timing of decelerations inability to monitor frequency of contractions as in the obese patient evaluation of contraction strength if patient’s labor process fails to progress. Requirements include the following: confirmed rupture of membranes (spontaneous or artificial) engaged vertex presenting part cervical dilatation of at least 1-2cm patient’s consent and ability to cooperate with sterile vaginal examination Contraindications Contraindications for use include the following: diagnosed or suspected placenta praevia undiagnosed vaginal bleeding non-rupture of amniotic membranes maternal infection (chorioamnionitis, active genital herpes, HIV) non-vertex fetal presentation any condition that precludes vaginal delivery Issues to Consider Potential complications for consideration infection postpartum endomyometritis uterine perforation umbilical core perforation CPP0487-Fetal Surveillance May 2019 cord entanglement extra-membranous catheter placement leading to complications (e.g. placental abruption, fetal distress, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and rarely anaphylactoid syndrome) Considerations To be discussed with the consultant on call and only inserted by senior registrar or consultant who is experienced in the procedure The intrauterine pressure catheter (IUPC) should not be left in situ for longer than 24 hours. Prior to attempting insertion the manufacturer’s product instructions should be read - different companies may have product insertion variations. -

Understanding Uterine Activity

Power and Passenger: Understanding Uterine Activity Michelle Flowers RNC-OB Emily Hamilton MDCM © 2017 PeriGen, Inc. Featuring Michelle Flowers, RNC-OB Program Manager Michelle Flowers serves as a PeriGen Program Manager & Clinical Consultant. Her 20+ year career also includes experience as a Clinical Quality Coordinator, Educator for obstetric services, and L&D charge nurse. Her more recent experience has focused on designing and executing OB documentation workflows and training programs. Her education credentials have included AWHONN Intermediate/Advanced Fetal Monitoring Instructor, ICEA Approved Trainer and Certified Childbirth Educator and AAP NRP Instructor. Featuring Emily Hamilton, MDCM Senior Vice President of Clinical Research An experienced obstetrician, Dr. Hamilton is currently an Adjunct Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at McGill University, as well as leading PeriGen’s clinical research team. Dr. Hamilton is the inventor of the PeriCALM advanced fetal monitoring system, holding 32 US and international patents for her research work. She is an internationally-known clinical thought leader on the use of technology to improve obstetric outcomes. She presents her research regularly at obstetric conferences and in peer-reviewed journals. Objectives 1. Review definitions related to uterine activity 2. Review etiology and physiology of uterine tachysystole 3. Analyze impact of UT on the fetal heart rate Uterine Contractions Quantified as the number of contractions in 10 minutes averaged over 30 minutes. • Uterine activity terminology used to assess and describe contractions: o Frequency – Beginning of contraction to beginning of next one o Duration – Length of contraction from beginning to end – Measured in seconds o Intensity – Strength of contraction – Assessed via palpation or mmHg (Montevideo units) o Resting Tone – Intrauterine pressure when uterus is not contracting – Assessed via palpation or mmHg Uterine Palpaon Palpation of uterine contractions is one of the key components of labor assessment. -

Management of Labor

Health Care Guideline Management of Labor How to cite this document: Creedon D, Akkerman D, Atwood L, Bates L, Harper C, Levin A, McCall C, Peterson D, Rose C, Setterlund L, Walkes B, Wingeier R. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Management of Labor. Updated March 2013. Copies of this ICSI Health Care Guideline may be distributed by any organization to the organization’s employees but, except as provided below, may not be distributed outside of the organization without the prior written consent of the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, Inc. If the organization is a legally constituted medical group, the ICSI Health Care Guideline may be used by the medical group in any of the following ways: • copies may be provided to anyone involved in the medical group’s process for developing and implementing clinical guidelines; • the ICSI Health Care Guideline may be adopted or adapted for use within the medical group only, provided that ICSI receives appropriate attribution on all written or electronic documents and • copies may be provided to patients and the clinicians who manage their care, if the ICSI Health Care Guideline is incorporated into the medical group’s clinical guideline program. All other copyright rights in this ICSI Health Care Guideline are reserved by the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. The Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement assumes no liability for any adap- tations or revisions or modifications made to this ICSI Health Care Guideline. www.icsi.org Copyright © 2013 by Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement Health Care Guideline and Order Set: Management of Labor 1 Pregnant patient > 20 Text in blue in this algorithm weeks with symptoms indicates a linked corresponding of labor Fifth Edition annotation. -

Labour Dystocia: Risk Factors and Consequences for Mother and Infant

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Publications from Karolinska Institutet Department of Medicine, Solna Clinical Epidemiology Unit Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden Labour dystocia: Risk factors and consequences for mother and infant Anna Sandström Stockholm 2016 All previously published papers were reproduced with permission from the publisher. Published by Karolinska Institutet. Printed by AJ E-print AB © Anna Sandström, 2016 ISBN 978-91-7676-414-5 Department of Medicine, Solna Clinical Epidemiology Unit Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden Labour dystocia: Risk factors and consequences for mother and infant THESIS FOR DOCTORAL DEGREE (Ph.D) To be publicly defended in Skandiasalen, Astrid Lindgrens Children’s Hospital, Karolinska University Hospital, Solna Friday October 14th, 2016 at 09.00 By Anna Sandström Principal Supervisor: Opponent: Olof Stephansson, Associate Professor Aaron B. Caughey, Professor Karolinska Institutet Oregon Health and Science University Department of Medicine, Solna Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinical Epidemiology Unit Examination Board: Co-supervisor: Ulf Högberg, Professor Sven Cnattingius, Professor Uppsala University Karolinska Institutet Department of Women’s and Children’s Health Department of Medicine, Solna Division of Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinical Epidemiology Unit Karin Petersson, Associate Professor Karolinska Insitutet Department of Clinical Science, Intervention and Technology (Clintec) Division of Obstetrics and Gynecology Ingela Rådestad, Professor Sophiahemmet University To my family Abstract Background: Labour dystocia (prolonged labour) occurs in the active first stage or in the second stage of labour. Dystocia affects approximately 21-37% of nulliparous, and 2-10% of parous women. The condition is associated with increased risks of maternal morbidities, instrumental vaginal deliveries and is the most common indication for a primary caesarean section. -

![Roberto Caldeyro-Barcia (1921–1996) [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3497/roberto-caldeyro-barcia-1921-1996-1-2843497.webp)

Roberto Caldeyro-Barcia (1921–1996) [1]

Published on The Embryo Project Encyclopedia (https://embryo.asu.edu) Roberto Caldeyro-Barcia (1921–1996) [1] By: Mandile, Olivia Keywords: Obstetrics [2] Roberto Caldeyro-Barcia studied fetal health in Uruguay during the second half of the twentieth century. Caldeyro-Barcia developed Montevideo units, which are used to quantify intrauterine pressure, or the force of contractions during labor. Intrauterine pressure is a useful measure of the progression of labor and the health of a fetus [3]. Caldeyro-Barcia’s research on fetal health often contradicted common obstetric practices, prompting him to publically challenge practices such as induction [4] of labor using oxytocin, forced pushing during labor, and birth position in which the woman lays on her back during labor. Caldeyro- Barcia’s methods of monitoring intrauterine pressure and development of Montevideo units furthered research in maternal and fetal health and improved the use of medical interventions during labor and delivery. Caldeyro-Barcia was born on 26 September 1921 in Montevideo, Uruguay. His mother, Elvira Barcia, came from a family with a medical background and his father, Joaquin Caldeyro, was a physician. Caldeyro-Barcia attended primary school at the English School in Montevideo, where he met fellow student Ofelia Stajano, whom he would later marry. As a teenager, Caldeyro-Barcia attended the Elbro Fernandez School in Montevideo, and began to court Stajano. In 1938, Caldeyro-Barcia entered the University of Uruguay’s Faculty of Medicine in Montevideo, where he studied medicine. During his time in school, Caldeyro-Barcia and Stajano became engaged. The couple married a year later in January 1946 and had six children, Ofelia, Lucia, Roberto, Carlos, Eduardo, and Martin. -

Intrauterine Migration of the Porcine Embryo

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF WILLIAM FREDERICK POPE for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in ANIMAL SCIENCE (PHYSIOLOGY) presented on November 6, 1981 Title: INTRAUTERINE MIGRATION OF THE PORCINE EMBYRO Abstract appoved: Redacted for privacy Fredrick Stormshak The mechanism(s) involved with intrauterine migration of the por- cine embryo was investigated. Twenty-four gilts on Days 6, 9 and 12 of gestation (Day 0 = 1st day of estrus) were utilized to examine the relationship between myometrial activity and intrauterine migration. On Day 2, embryos were flushed from one oviduct and transferred to the opposite oviduct. Myometrial contractility increased concomitant with embryo migration through the uterus (day x side interaction, P<.10). Uterine flushings contained a short-acting component that mimicked, in part, the stimulatory influence(s) of the porcine embryo on myometrial activity. Furthermore, only flushings from the uterine segment con- taining the Day 12 embryos could overcome the inhibitory effects of indomethacin (P<.01) on myometrial activity. The porcine embryo coin- cubated with myometrial strips could not directly stimulate myometrial activity. The role of estradio1-17B (E2) and histamine in migration of the porcine embryo was examined. The involvement of E2in embryo migra- tion was examined by observing the distribution of silastic beads impregnated with cholesterol (five gilts) or E2 (five gilts) on Day 12 of the estrous cycle (after 5 days in utero). Beads impregnated with E2 migrated further (P<.05) than those impregnated with cholesterol. Twenty additional gilts and sows were assigned to four groups (n = 5) and were used to determine if histamine was involved with intrauterine migration. -

![Intrauterine Pressure Catheter [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4592/intrauterine-pressure-catheter-1-3534592.webp)

Intrauterine Pressure Catheter [1]

Published on The Embryo Project Encyclopedia (https://embryo.asu.edu) Intrauterine Pressure Catheter [1] By: Mandile, Olivia An intrauterine pressure catheter (IUPC) is a device placed inside a pregnant woman’su terus [2] to monitor uterine contractions during labor. During labor, a woman’s uterus [2] contracts to dilate, or open, the cervix [3] and push the fetus [4] into the birth canal. The catheter measures the pressure within the amniotic space during contractions and allows physicians to evaluate the strength, frequency, and duration of contractions. Those measurements enable physicians to evaluate the progression of labor and intervene when contractions are too weak to properly dilate a laboring woman’s cervix [3] to successfully deliver a fetus [4]. Though IUPCs are not used routinely, they are important in cases where external fetal monitoring is not sufficient to monitor a difficult labor. Intrauterine pressure catheters give physicians an extremely accurate measurement of intrauterine pressure, making it possible to determine whether intervention is needed to progress the labor. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, physicians attempted to monitor the progression of labor through the study of uterine contractions. In the late 19th century, physicians developed a microballoon that could be inserted between the membranes of the uterus [2] and the uterine wall to measure intrauterine pressure. In the early 20th century, physicians began inserting catheters through the pregnant woman’s abdomen and the uterus [2] into the amniotic space. However, both these procedures were considered experimental, not performed frequently, and often not reported until later in the twentieth century. In the mid-twentieth century, physicians developed an intrauterine pressure catheter that could be inserted transcervically, or through the cervix [3].