Labour Dystocia: Risk Factors and Consequences for Mother and Infant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preventing the First Cesarean Delivery

Current Commentary Preventing the First Cesarean Delivery Summary of a Joint Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Society for Maternal- Fetal Medicine, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Workshop Catherine Y. Spong, MD, Vincenzo Berghella, MD, Katharine D. Wenstrom, MD, Brian M. Mercer, MD, and George R. Saade, MD points were identified to assist with reduction in cesar- With more than one third of pregnancies in the United ean delivery rates including that labor induction should States being delivered by cesarean and the growing be performed primarily for medical indication; if done knowledge of morbidities associated with repeat cesar- for nonmedical indications, the gestational age should be ean deliveries, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Insti- at least 39 weeks or more and the cervix should be favor- tute of Child Health and Human Development, the able, especially in the nulliparous patient. Review of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and the American current literature demonstrates the importance of adher- College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists convened ing to appropriate definitions for failed induction and a workshop to address the concept of preventing the first arrest of labor progress. The diagnosis of “failed induc- cesarean delivery. The available information on maternal tion” should only be made after an adequate attempt. and fetal factors, labor management and induction, and Adequate time for normal latent and active phases of nonmedical factors leading to the first cesarean delivery the first stage, and for the second stage, should be was reviewed as well as the implications of the first allowed as long as the maternal and fetal conditions per- cesarean delivery on future reproductive health. -

NUR 306- MIDWIWERY-II.Pdf

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF EASTERN AFRICA P.O. Box 62157 A. M. E. C. E. A 00200 Nairobi - KENYA Telephone: 891601-6 Fax: 254-20-891084 MAIN EXAMINATION E-mail:[email protected] SEPTEMBER-DECEMBER 2020 TRIMESTER SCHOOL OF NURSING REGULAR PROGRAMME NUR/UNUR 306: MIDWIFERY II-LABOUR Date: DECEMBER2020 Duration: 3 Hours INSTRUCTIONS: i. All questions are compulsory ii. Indicate the answers in the answer booklet provided PART -I: MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS (MCQs) (20 MARKS): Q1.The following are two emergencies that can occur in third stage of labour: a) Cord prolapsed, foetal distress. b) Ruptured uterus ,foetal distress. c) Uterine inversion, cord pulled off. d) Cord round the neck, foetal distress. Q2 A woman in preterm labor at 30 weeks of gestation receives two 12-mg doses of betamethasone intramuscularly. The purpose of this pharmacologic treatment is to: a). Stimulate fetal surfactant production. b). Reduce maternal and fetal tachycardia associated with ritodrine administration. c). Suppress uterine contractions. d). Maintain adequate maternal respiratory effort and ventilation during magnesium sulfate therapy. Q3. Episiotomy should only be considered in case of : a) Breech, vacuum delivery, scarring from genital cutting, fetal distress. b) Primigravida, disturbed woman, genital cutting, obstructed labor. c) Obstructed labor, hypertonic contractions, multigravida, forceps delivery. Cuea/ACD/EXM/APRIL 2020/SCHOOL OF NURSING Page 1 ISO 9001:2015 Certified by the Kenya Bureau of Standards d) Primigravida, hypotonic contractions, fetal distress, genital cutting. Q4.A multiporous woman in labour tells the midwife “I feel like opening the bowels”.How should the midwife respond? a) Allow the woman to use the bedpan. -

Delivery Mode for Prolonged, Obstructed Labour Resulting in Obstetric Fistula: a Etrr Ospective Review of 4396 Women in East and Central Africa

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eCommons@AKU eCommons@AKU Obstetrics and Gynaecology, East Africa Medical College, East Africa 12-17-2019 Delivery mode for prolonged, obstructed labour resulting in obstetric fistula: a etrr ospective review of 4396 women in East and Central Africa C. J. Ngongo T. J. Raassen L. Lombard J van Roosmalen S. Weyers See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/eastafrica_fhs_mc_obstet_gynaecol Part of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Commons Authors C. J. Ngongo, T. J. Raassen, L. Lombard, J van Roosmalen, S. Weyers, and Marleen Temmerman DOI: 10.1111/1471-0528.16047 www.bjog.org Delivery mode for prolonged, obstructed labour resulting in obstetric fistula: a retrospective review of 4396 women in East and Central Africa CJ Ngongo,a TJIP Raassen,b L Lombard,c J van Roosmalen,d,e S Weyers,f M Temmermang,h a RTI International, Seattle, WA, USA b Nairobi, Kenya c Cape Town, South Africa d Athena Institute VU University Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands e Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden, The Netherlands f Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Ghent University Hospital, Ghent, Belgium g Centre of Excellence in Women and Child Health, Aga Khan University, Nairobi, Kenya h Faculty of Medicine and Health Science, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium Correspondence: CJ Ngongo, RTI International, 119 S Main Street, Suite 220, Seattle, WA 98104, USA. Email: [email protected] Accepted 3 December 2019. Objective To evaluate the mode of delivery and stillbirth rates increase occurred at the expense of assisted vaginal delivery over time among women with obstetric fistula. -

Labor and Vaginal Delivery

VI LABOR, DELIVERY, AND POSTPARTUM LABOR AND VAGINAL DELIVERY Kelly A. Best, MD CHAPTER 61 1. What is the definition of labor? Labor begins when uterine contractions of sufficient frequency, intensity, and duration are attained to bring about effacement and progressive dilation of the cervix. 2. What two steps are theorized to be crucial to the initiation of labor in human pregnancy? 1. Retreat from pregnancy maintenance 2. Uterotonic induction Despite extensive investigation into the associated physiologic and biochemical changes, the physiologic processes in human pregnancy that result in the onset of labor are still not defined. 3. In which patients is induction of labor considered? Awaiting the onset of normal labor may not be an option in certain circumstances. At preterm gestations, indications for labor induction include severe preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction with abnormal antepartum surveillance or other evidence of fetal compromise, and deterioration of maternal disease to the point that continuation of pregnancy is believed to be detrimental. In cases of rupture of membranes without labor (i.e., premature rupture of membranes) at term (37 to 42 weeks) or postterm (≥42 weeks), induction of labor is often performed. 4. What is a Bishop score, and how is it used? A Bishop score is a quantifiable method to assess the likelihood of a successful induction. Elements include dilation, effacement, station, consistency, and position of the cervix (Table 61-1). A score of 6 or less trans- lates into a need to ripen the cervix and is associated with less successful inductions. A score 8 or greater generally means the cervix does not need ripening and induction is more likely to be successful. -

A Guide to Obstetrical Coding Production of This Document Is Made Possible by Financial Contributions from Health Canada and Provincial and Territorial Governments

ICD-10-CA | CCI A Guide to Obstetrical Coding Production of this document is made possible by financial contributions from Health Canada and provincial and territorial governments. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada or any provincial or territorial government. Unless otherwise indicated, this product uses data provided by Canada’s provinces and territories. All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be reproduced unaltered, in whole or in part and by any means, solely for non-commercial purposes, provided that the Canadian Institute for Health Information is properly and fully acknowledged as the copyright owner. Any reproduction or use of this publication or its contents for any commercial purpose requires the prior written authorization of the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Reproduction or use that suggests endorsement by, or affiliation with, the Canadian Institute for Health Information is prohibited. For permission or information, please contact CIHI: Canadian Institute for Health Information 495 Richmond Road, Suite 600 Ottawa, Ontario K2A 4H6 Phone: 613-241-7860 Fax: 613-241-8120 www.cihi.ca [email protected] © 2018 Canadian Institute for Health Information Cette publication est aussi disponible en français sous le titre Guide de codification des données en obstétrique. Table of contents About CIHI ................................................................................................................................. 6 Chapter 1: Introduction .............................................................................................................. -

Chapter 9 Risk Factors

Chapter 9 Risk factors 9.1 Introduction The previous chapters have all focused on adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes as risk factors for foetal loss and neonatal death. The present chapter takes the discussion and analysis one layer further to the underlying risk factors for the selected adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes themselves. These risk factors are more remote in the causal chain and include maternal factors, complications of the placenta, cord, and membranes, and birth complications. These have been referred to earlier, in Chapter 3, in the operationalisation of the conceptual model (Figure 3.6). Besides their direct effect on pregnancy/birth outcome, they are believed to affect foetal loss (i.e. spontaneous abortion and stillbirth), both directly and indirectly, and neonatal death indirectly through the intermediate outcomes (i.e. adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes). As became clear in Chapter 3, many different causes and risk factors underlie the adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes, but what appear to be main risk factors? Are these risk factors also important in regions in transition and, more specifically, in Kerala? Moreover, does the relative importance of these risk factors change during the epidemiologic transition? A region’s position within the transition could very well be reflected by its specific combination of underlying risk factors. Factors such as infections and malnutrition are likely to be important during the early of the transition, while others such as diabetes and advanced maternal age may become more significant during later stages. This could lead to a redefinition of the concepts of endogenous and exogenous mortality (see Chapter 2). -

2020 CDA Paper Abstraction Forms

2020 OBI DATA ABSTRACTION FORMS DEMOGRAPHICS Hospital Name: Patient Last Name: Patient First Name: Medical Record Number (MRN): Maternal Birthdate (MM/DD/YY): Postal Zip Hispanic Ethnicity: Code: Hispanic or Latino Not Hispanic or Latino Race (select all that apply): Unknown American Indian or Alaskan Native Asian Patient's Insurance Type: Black or African American Medicaid Self Pay/None Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander Private Other: __________ White Unknown LABOR MANAGEMENT: Admission L&D Admission Date: L&D Admission Time: Provider admitting patient to Labor & Delivery (Last Name, First Name): Service/Practice patient admitted to: Admitting Nurse (Last name, First name): Certified Nurse Midwife Family Practice / Family Medicine Gravidity on admission: Parity on admission: Maternal Fetal Medicine Obstetrics Physician Maternal Height at admission: Maternal Weight at admission: Pre-pregnancy Weight: IN LBS LBS CM K G KG Did the patient receive prenatal care? If yes, date prenatal care Transfer of care from an intended home birth? started: Yes No Unable to determine Yes No LABOR MANAGEMENT: Maternal Comorbidities Present On Admission Pre-pregnancy diabetes (Type I or Type II Yes Was the patient using opioids during this Yes diabetes diagnosed prior to this pregnancy) No pregnancy? No Gestational diabetes (diagnosis in this pregnancy Yes What was the status of the patient's opioid use during this with or without medication tx) No pregnancy? (select all that apply): In treatment for opioid use disorder during pregnancy Pre-pregnancy -

OBGYN-Study-Guide-1.Pdf

OBSTETRICS PREGNANCY Physiology of Pregnancy: • CO input increases 30-50% (max 20-24 weeks) (mostly due to increase in stroke volume) • SVR anD arterial bp Decreases (likely due to increase in progesterone) o decrease in systolic blood pressure of 5 to 10 mm Hg and in diastolic blood pressure of 10 to 15 mm Hg that nadirs at week 24. • Increase tiDal volume 30-40% and total lung capacity decrease by 5% due to diaphragm • IncreaseD reD blooD cell mass • GI: nausea – due to elevations in estrogen, progesterone, hCG (resolve by 14-16 weeks) • Stomach – prolonged gastric emptying times and decreased GE sphincter tone à reflux • Kidneys increase in size anD ureters dilate during pregnancy à increaseD pyelonephritis • GFR increases by 50% in early pregnancy anD is maintaineD, RAAS increases = increase alDosterone, but no increaseD soDium bc GFR is also increaseD • RBC volume increases by 20-30%, plasma volume increases by 50% à decreased crit (dilutional anemia) • Labor can cause WBC to rise over 20 million • Pregnancy = hypercoagulable state (increase in fibrinogen anD factors VII-X); clotting and bleeding times do not change • Pregnancy = hyperestrogenic state • hCG double 48 hours during early pregnancy and reach peak at 10-12 weeks, decline to reach stead stage after week 15 • placenta produces hCG which maintains corpus luteum in early pregnancy • corpus luteum produces progesterone which maintains enDometrium • increaseD prolactin during pregnancy • elevation in T3 and T4, slight Decrease in TSH early on, but overall euthyroiD state • linea nigra, perineum, anD face skin (melasma) changes • increase carpal tunnel (median nerve compression) • increased caloric need 300cal/day during pregnancy and 500 during breastfeeding • shoulD gain 20-30 lb • increaseD caloric requirements: protein, iron, folate, calcium, other vitamins anD minerals Testing: In a patient with irregular menstrual cycles or unknown date of last menstruation, the last Date of intercourse shoulD be useD as the marker for repeating a urine pregnancy test. -

Pretest Obstetrics and Gynecology

Obstetrics and Gynecology PreTestTM Self-Assessment and Review Notice Medicine is an ever-changing science. As new research and clinical experience broaden our knowledge, changes in treatment and drug therapy are required. The authors and the publisher of this work have checked with sources believed to be reliable in their efforts to provide information that is complete and generally in accord with the standards accepted at the time of publication. However, in view of the possibility of human error or changes in medical sciences, neither the authors nor the publisher nor any other party who has been involved in the preparation or publication of this work warrants that the information contained herein is in every respect accurate or complete, and they disclaim all responsibility for any errors or omissions or for the results obtained from use of the information contained in this work. Readers are encouraged to confirm the information contained herein with other sources. For example and in particular, readers are advised to check the prod- uct information sheet included in the package of each drug they plan to administer to be certain that the information contained in this work is accurate and that changes have not been made in the recommended dose or in the contraindications for administration. This recommendation is of particular importance in connection with new or infrequently used drugs. Obstetrics and Gynecology PreTestTM Self-Assessment and Review Twelfth Edition Karen M. Schneider, MD Associate Professor Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences University of Texas Houston Medical School Houston, Texas Stephen K. Patrick, MD Residency Program Director Obstetrics and Gynecology The Methodist Health System Dallas Dallas, Texas New York Chicago San Francisco Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi San Juan Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto Copyright © 2009 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. -

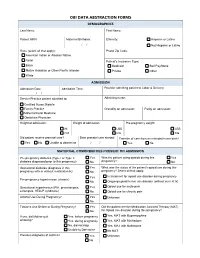

Obi Data Abstraction Forms Demographics

OBI DATA ABSTRACTION FORMS DEMOGRAPHICS Last Name: First Name: Patient MRN: Maternal Birthdate: Ethnicity: Hispanic or Latino / / Not Hispanic or Latino Race (select all that apply): Postal Zip Code: American Indian or Alaskan Native Asian Patient's Insurance Type: Black Medicaid Self Pay/None Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander Private Other White ADMISSION Admission Date: Admission Time: Provider admitting patient to Labor & Delivery: / / Service/Practice patient admitted to: Admitting nurse: Certified Nurse Midwife Family Practice Gravidity on admission: Parity on admission: Maternal Fetal Medicine Obstetrics Physician Height at admission: Weight at admission: Pre-pregnancy weight: IN LBS LBS CM KG KG Did patient receive prenatal care? Date prenatal care started: Transfer of care from an intended home birth? Yes No Unable to determine / / Yes No MATERNAL COMORBIDITIES PRESENT ON ADMISSION Pre-pregnancy diabetes (Type I or Type II Yes Was the patient using opioids during this Yes diabetes diagnosed prior to this pregnancy) No pregnancy? No Gestational diabetes (diagnosis in this Yes What was the status of the patient's opioid use during this pregnancy with or without medication tx) No pregnancy? Select all that apply: Yes In treatment for opioid use disorder during pregnancy Pre-pregnancy hypertension (chronic) No Ongoing opioid/heroin use disorder (without current tx) Gestational hypertension (PIH, preeclampsia, Yes Opioid use for acute pain eclampsia, HELLP syndrome) No Opioid use for chronic pain Alcohol Use During Pregnancy? -

Table of Contents

Problem-Based Clinical Cases Obstetrics and Gynecology Rotation Gyn Cases Updated December 2004 OB Cases Updated June 2005 By Dr. Manisha Patel Table of Contents Section I: General Gynecology Page 4. Breast Disorders..................................................................................................................................... 1 5. Contraception ......................................................................................................................................... 2 7. Dysmenorrhea........................................................................................................................................ 3 8. Dyspareunia ........................................................................................................................................... 5 9. Ectopic Pregnancy.................................................................................................................................. 8 10. Enlarged Uterus...................................................................................................................................... 9 19. Menorrhagia ......................................................................................................................................... 10 23. Pelvic Relaxation .................................................................................................................................. 12 25. Postmenopausal Bleeding................................................................................................................... -

Appendix 1. Coding of All Adverse Maternal and Newborn Outcomes

Appendix 1. Coding of All Adverse Maternal and Newborn Outcomes Adverse Outcome Source Variables Coding Preeclampsia Superimposed preeclampsia ICD-10 Pre-existing hypertensive disorder with O11.001- superimposed proteinuria O11.004, O11.009 Preeclampsia ICD-10 Gestational (pregnancy-induced) O13.001- hypertension without significant O13.004, proteinuria (includes gHTN and mild pre- O13.009 eclampsia) Gestational (pregnancy-induced) O14.001- hypertension with significant proteinuria O14.004, O14.009 ICD-10 Unspecified maternal hypertension O16.001- O16.004, O16.009 ICD-10 Eclampsia in pregnancy, labour, O15.001- puerperium, unspecified time O15.909 Gestational diabetes mellitus Gestational diabetes ICD-10 Diabetes mellitus arising in pregnancy O24.801- (gestational) O24.804, O24.809 Gestational diabetes BCPDR Insulin-dependent or non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus in pregnancy Spontaneous preterm birth <32 weeks Gestational age <32 weeks BCPDR Final estimate of gestational age per BCPDR algorithm Induction of labor BCPDR Labour initiation No PROM ICD-10 Premature rupture of membranes O42.011- O42.909 Indicated preterm birth <37 weeks Schummers L, Hutcheon JA, Bodnar LM, Lieberman E, Himes KP. Risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes by prepregnancy body mass index: a population-based study to inform prepregnancy weight loss counseling. Obstet Gynecol 2014;125. The authors provided this information as a supplement to their article. © Copyright 2014 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Page 1 of 7 Gestational age <37 weeks