Molecular Elucidation of a Urate Oxidase from Deinococcus Radiodurans for Hyperuricemia and Gout Therapy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table S1. List of Genes Up- Or Down-Regulated in H99 When Bound by 18B7

Table S1. List of genes up- or down-regulated in H99 when bound by 18B7. Up-regulated Genes Classification CNF03470: Formate dehydrogenase Metabolism CNC03960: Phosphate transporter, putative Metabolism CND00530: Putative urea transporter Secretion CNA02250: Ammonium transporter MEP1 Secretion CNC06440: Inositol 1-phosphate synthase Metabolism CND03490: Chitin deacetylase-like mannoprotein MP98 Cell wall CNA04560: Hypothetical protein Hypothetical CNF02180: Acetyl-CoA carboxylase, putative Metabolism CNJ00690: Uracil permease, putative Secretion CNF02510: Alcohol dehydrogenase, putative Metabolism CNE04360: Fatty acid synthase, alpha subunit-related Metabolism CNM00180: Cyclohydrolase, putative Metabolism CNL03740: AF540951 catalase isozyme P Stress CNE04370: Fatty acid synthase, beta subunit Metabolism CNA01790: Expressed protein Hypothetical CNA05700: Expressed protein Hypothetical CND03840: Vacuole fusion, non-autophagic-related protein, putative Cell wall CNM00980: Hypothetical protein Hypothetical CNI02420: Uricase (Urate oxidase), putative Metabolism CNJ01090: Xylitol dehydrogenase-related Cell wall CNC03430: Alpha-1,6-mannosyltransferase, putative Cell wall CNF04120: Expressed protein Hypothetical CNB01810: Short chain dehydrogenase, putative Metabolism CNJ01200: Hypothetical protein Hypothetical CNA01160: LSDR putative Metabolism CNH03430: Hypothetical protein Hypothetical CNM02410: Putative proteine disulfate isomerase Housekeeping CNG04200: Alpha-amylase, putative Cell wall CNC00920: NADP-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase Metabolism -

Nucleotide Metabolism 22

Nucleotide Metabolism 22 For additional ancillary materials related to this chapter, please visit thePoint. I. OVERVIEW Ribonucleoside and deoxyribonucleoside phosphates (nucleotides) are essential for all cells. Without them, neither ribonucleic acid (RNA) nor deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) can be produced, and, therefore, proteins cannot be synthesized or cells proliferate. Nucleotides also serve as carriers of activated intermediates in the synthesis of some carbohydrates, lipids, and conjugated proteins (for example, uridine diphosphate [UDP]-glucose and cytidine diphosphate [CDP]- choline) and are structural components of several essential coenzymes, such as coenzyme A, flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD[H2]), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD[H]), and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP[H]). Nucleotides, such as cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), serve as second messengers in signal transduction pathways. In addition, nucleotides play an important role as energy sources in the cell. Finally, nucleotides are important regulatory compounds for many of the pathways of intermediary metabolism, inhibiting or activating key enzymes. The purine and pyrimidine bases found in nucleotides can be synthesized de novo or can be obtained through salvage pathways that allow the reuse of the preformed bases resulting from normal cell turnover. [Note: Little of the purines and pyrimidines supplied by diet is utilized and is degraded instead.] II. STRUCTURE Nucleotides are composed of a nitrogenous base; a pentose monosaccharide; and one, two, or three phosphate groups. The nitrogen-containing bases belong to two families of compounds: the purines and the pyrimidines. A. Purine and pyrimidine bases Both DNA and RNA contain the same purine bases: adenine (A) and guanine (G). -

SUPPY Liglucosexlmtdh

US 20100314248A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/0314248 A1 Worden et al. (43) Pub. Date: Dec. 16, 2010 (54) RENEWABLE BOELECTRONIC INTERFACE Publication Classification FOR ELECTROBOCATALYTC REACTOR (51) Int. Cl. (76) Inventors: Robert M. Worden, Holt, MI (US); C25B II/06 (2006.01) Brian L. Hassler, Lake Orion, MI C25B II/2 (2006.01) (US); Lawrence T. Drzal, Okemos, GOIN 27/327 (2006.01) MI (US); Ilsoon Lee, Okemo s, MI BSD L/04 (2006.01) (US) C25B 9/00 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. ............... 204/403.14; 204/290.11; 204/400; Correspondence Address: 204/290.07; 427/458; 204/252: 977/734; PRICE HENEVELD COOPER DEWITT & LIT 977/742 TON, LLP 695 KENMOOR, S.E., PO BOX 2567 (57) ABSTRACT GRAND RAPIDS, MI 495.01 (US) An inexpensive, easily renewable bioelectronic device useful for bioreactors, biosensors, and biofuel cells includes an elec (21) Appl. No.: 12/766,169 trically conductive carbon electrode and a bioelectronic inter face bonded to a surface of the electrically conductive carbon (22) Filed: Apr. 23, 2010 electrode, wherein the bioelectronic interface includes cata lytically active material that is electrostatically bound directly Related U.S. Application Data or indirectly to the electrically conductive carbon electrode to (60) Provisional application No. 61/172,337, filed on Apr. facilitate easy removal upon a change in pH, thereby allowing 24, 2009. easy regeneration of the bioelectronic interface. 7\ POWER 1 - SUPPY|- LIGLUCOSEXLMtDH?till pi 6.0 - esses&aaaas-exx-xx-xx-xx-xxxxixax-e- Patent Application Publication Dec. 16, 2010 Sheet 1 of 18 US 2010/0314248 A1 Potential (nV) Patent Application Publication Dec. -

Monitoring the Redox Status in Multiple Sclerosis

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 31 July 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202007.0737.v1 Review Monitoring the Redox Status in Multiple Sclerosis Masaru Tanaka 1,2 and László Vécsei 1,2,* 1 MTA-SZTE, Neuroscience Research Group, Semmelweis u. 6, Szeged, H-6725 Hungary; [email protected] 2 Department of Neurology, Interdisciplinary Excellence Centre, Faculty of Medicine, University of Szeged, Semmelweis u. 6, H-6725 Szeged, Hungary * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +36-62-545-351 Received: date; Accepted: date; Published: date Abstract: Worldwide, over 2.2 million people are suffered from multiple sclerosis (MS), a multifactorial demyelinating disease of the central nervous system, characterized by multifocal inflammatory or demyelinating attacks associated with neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. The blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and postmortem brain samples of MS patients evidenced the presence of reduction-oxidation (redox) homeostasis disturbance such as the alternations of oxidative and antioxidative enzyme activities and the presence of degradation products. This review article discussed the components of redox homeostasis including reactive chemical species, oxidative enzymes, antioxidative enzymes, and degradation products. The reactive chemical species covered frequently discussed reactive oxygen/nitrogen species, rarely featured reactive chemicals such as sulfur, carbonyls, halogens, selenium, and nucleophilic species that potentially act as reductive as well as pro-oxidative stressors. The antioxidative enzyme systems covered the nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2 (NRF2)-Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1) signaling pathway, a possible biomarker sensitive to the initial phase of oxidative stress. Altered components of the redox homeostasis in MS were discussed, some of which turned to be MS subtype- or treatment-specific and thus potentially become diagnostic, prognostic, predictive, and/or therapeutic biomarkers. -

Source: the Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR);

Table S1 List of targeted loci and information about their function in Arabidopsis thaliana (source: The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR); https://www.arabidopsis.org/tools/bulk/genes/index.jsp). Locus Gene Model Gene Model Description Gene Model Primary Gene Symbol All Gene Symbols Identifier Name Type AT1G78800 AT1G78800.1 UDP-Glycosyltransferase superfamily protein_coding protein;(source:Araport11) AT5G06830 AT5G06830.1 hypothetical protein;(source:Araport11) protein_coding AT2G31740 AT2G31740.1 S-adenosyl-L-methionine-dependent methyltransferases protein_coding superfamily protein;(source:Araport11) AT5G11960 AT5G11960.1 magnesium transporter, putative protein_coding (DUF803);(source:Araport11) AT4G00560 AT4G00560.4 NAD(P)-binding Rossmann-fold superfamily protein_coding protein;(source:Araport11) AT1G80510 AT1G80510.1 Encodes a close relative of the amino acid transporter ANT1 protein_coding (AT3G11900). AT2G21250 AT2G21250.1 NAD(P)-linked oxidoreductase superfamily protein_coding protein;(source:Araport11) AT5G04420 AT5G04420.1 Galactose oxidase/kelch repeat superfamily protein_coding protein;(source:Araport11) AT4G34910 AT4G34910.1 P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases protein_coding superfamily protein;(source:Araport11) AT5G66120 AT5G66120.2 3-dehydroquinate synthase;(source:Araport11) protein_coding AT1G45110 AT1G45110.1 Tetrapyrrole (Corrin/Porphyrin) protein_coding Methylase;(source:Araport11) AT1G67420 AT1G67420.2 Zn-dependent exopeptidases superfamily protein_coding protein;(source:Araport11) AT3G62370 -

O O2 Enzymes Available from Sigma Enzymes Available from Sigma

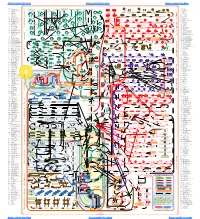

COO 2.7.1.15 Ribokinase OXIDOREDUCTASES CONH2 COO 2.7.1.16 Ribulokinase 1.1.1.1 Alcohol dehydrogenase BLOOD GROUP + O O + O O 1.1.1.3 Homoserine dehydrogenase HYALURONIC ACID DERMATAN ALGINATES O-ANTIGENS STARCH GLYCOGEN CH COO N COO 2.7.1.17 Xylulokinase P GLYCOPROTEINS SUBSTANCES 2 OH N + COO 1.1.1.8 Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase Ribose -O - P - O - P - O- Adenosine(P) Ribose - O - P - O - P - O -Adenosine NICOTINATE 2.7.1.19 Phosphoribulokinase GANGLIOSIDES PEPTIDO- CH OH CH OH N 1 + COO 1.1.1.9 D-Xylulose reductase 2 2 NH .2.1 2.7.1.24 Dephospho-CoA kinase O CHITIN CHONDROITIN PECTIN INULIN CELLULOSE O O NH O O O O Ribose- P 2.4 N N RP 1.1.1.10 l-Xylulose reductase MUCINS GLYCAN 6.3.5.1 2.7.7.18 2.7.1.25 Adenylylsulfate kinase CH2OH HO Indoleacetate Indoxyl + 1.1.1.14 l-Iditol dehydrogenase L O O O Desamino-NAD Nicotinate- Quinolinate- A 2.7.1.28 Triokinase O O 1.1.1.132 HO (Auxin) NAD(P) 6.3.1.5 2.4.2.19 1.1.1.19 Glucuronate reductase CHOH - 2.4.1.68 CH3 OH OH OH nucleotide 2.7.1.30 Glycerol kinase Y - COO nucleotide 2.7.1.31 Glycerate kinase 1.1.1.21 Aldehyde reductase AcNH CHOH COO 6.3.2.7-10 2.4.1.69 O 1.2.3.7 2.4.2.19 R OPPT OH OH + 1.1.1.22 UDPglucose dehydrogenase 2.4.99.7 HO O OPPU HO 2.7.1.32 Choline kinase S CH2OH 6.3.2.13 OH OPPU CH HO CH2CH(NH3)COO HO CH CH NH HO CH2CH2NHCOCH3 CH O CH CH NHCOCH COO 1.1.1.23 Histidinol dehydrogenase OPC 2.4.1.17 3 2.4.1.29 CH CHO 2 2 2 3 2 2 3 O 2.7.1.33 Pantothenate kinase CH3CH NHAC OH OH OH LACTOSE 2 COO 1.1.1.25 Shikimate dehydrogenase A HO HO OPPG CH OH 2.7.1.34 Pantetheine kinase UDP- TDP-Rhamnose 2 NH NH NH NH N M 2.7.1.36 Mevalonate kinase 1.1.1.27 Lactate dehydrogenase HO COO- GDP- 2.4.1.21 O NH NH 4.1.1.28 2.3.1.5 2.1.1.4 1.1.1.29 Glycerate dehydrogenase C UDP-N-Ac-Muramate Iduronate OH 2.4.1.1 2.4.1.11 HO 5-Hydroxy- 5-Hydroxytryptamine N-Acetyl-serotonin N-Acetyl-5-O-methyl-serotonin Quinolinate 2.7.1.39 Homoserine kinase Mannuronate CH3 etc. -

A Conserved Role of the Insulin-Like Signaling Pathway in Diet-Dependent Uric Acid Pathologies in Drosophila Melanogaster

RESEARCH ARTICLE A conserved role of the insulin-like signaling pathway in diet-dependent uric acid pathologies in Drosophila melanogaster 1¤ 1,2 1,2 1 Sven Lang *, Tyler A. Hilsabeck , Kenneth A. WilsonID , Amit SharmaID , 1 3 1 4 Neelanjan Bose , Deanna J. Brackman , Jennifer N. BeckID , Ling Chen , Mark 1 5 4 1 3 A. WatsonID , David W. KillileaID , Sunita Ho , Arnold Kahn , Kathleen GiacominiID , Marshall L. Stoller6, Thomas Chi6, Pankaj Kapahi1* a1111111111 1 The Buck Institute for Research on Aging, Novato, California, United States of America, 2 Davis School of Gerontology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, United States of America, a1111111111 3 Department of Bioengineering and Therapeutic Sciences, University of California San Francisco, San a1111111111 Francisco, California, United States of America, 4 Division of Biomaterials and Bioengineering, University of a1111111111 California San Francisco, San Francisco, California, United States of America, 5 Nutrition & Metabolism a1111111111 Center, Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute, Oakland, California, United States of America, 6 Department of Urology, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California, United States of America ¤ Current address: Department of Medical Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Saarland University, Homburg, Germany. OPEN ACCESS * [email protected] (SL); [email protected] (PK) Citation: Lang S, Hilsabeck TA, Wilson KA, Sharma A, Bose N, Brackman DJ, et al. (2019) A conserved role of the insulin-like signaling pathway in diet- Abstract dependent uric acid pathologies in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Genet 15(8): e1008318. Elevated uric acid (UA) is a key risk factor for many disorders, including metabolic syn- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1008318 drome, gout and kidney stones. -

Modeling Uric Acid Kidney Stones Disease in D. Melanogaster Using Rnai and Dietary Modulation

Dominican Scholar Graduate Master's Theses, Capstones, and Culminating Projects Student Scholarship 5-2015 Modeling Uric Acid Kidney Stones Disease in D. melanogaster using RNAi and Dietary Modulation Hai T.H. Lu Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2015.bio.05 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Lu, Hai T.H., "Modeling Uric Acid Kidney Stones Disease in D. melanogaster using RNAi and Dietary Modulation" (2015). Graduate Master's Theses, Capstones, and Culminating Projects. 178. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2015.bio.05 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Master's Theses, Capstones, and Culminating Projects by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modeling Uric Acid Kidney Stones Disease in D. melanogaster using RNAi and Dietary Modulation a thesis submitted to faculty of Dominican University of California and the Buck Institute for Research on Aging in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree Master of Science in Biology By Hai Lu San Rafael, California 2014 Copyright by Hai Lu 2014 Certification of Approval I certify that I have read Modeling Uric Acid Kidney Stones Disease in D. melanogaster using RNAi and Dietary Modulation By Hai Lu, and I approved this thesis to be submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree: Master of Sciences in Biology at Dominican University of California & the Buck Institute for Research on Ageing. -

REVIEW Treatment by Design in Leukemia, a Meeting Report

Leukemia (2003) 17, 2358–2382 & 2003 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0887-6924/03 $25.00 www.nature.com/leu REVIEW Treatment by design in leukemia, a meeting report, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, December 2002 RA Larson1, GQ Daley2, CA Schiffer3, P Porcu4, C-H Pui5, J-P Marie6, LS Steelman7, FE Bertrand7 and JA McCubrey7,8 1Section of Hematology/Oncology, University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA; 2Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research and Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA, USA; 3Wayne State University School of Medicine, Karmanos Cancer Institute, Detroit, MI, USA; 4Division of Hematology Oncology, Ohio State University College of Medicine and Public Health, Columbus, OH, USA; 5St Jude Children’s Research Hospital and the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN, USA; 6Onco-Hematology Department, Hoˆtel-Dieu de Paris, Paris, AP-HP, France; 7Department of Microbiology and Immunology, The Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University, Greenville, NC, USA; and 8Leo Jenkins Cancer Center, The Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University, Greenville, NC, USA Novel approaches have been designed to treat leukemia based disseminated cancer was ushered in approximately 50 years on our understanding of the genetic and biochemical lesions ago, when investigators recognized that inhibiting folate present in different malignancies. This meeting report sum- marizes some of the recent advances in leukemia treatment. metabolism led to the death of childhood leukemia cells. Based on the discoveries of cellular oncogenes, chromosomal Methotrexate, which inhibits dihydrofolate reductase and other translocations, monoclonal antibodies, multidrug resistance enzymes, is still a cornerstone of treatment for acute lympho- pumps, signal transduction pathways, genomics/proteonomic blastic leukemia (ALL), although it has a minimal role in acute approaches to clinical diagnosis and mutations in biochemical myeloid leukemia (AML). -

Uric Acid Degrading Enzymes, Urate Oxidase and Allantoinase, Are Associated with Different Subcellular Organelles in Frog Liver and Kidney

Journal of Cell Science 107, 1073-1081 (1994) 1073 Printed in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists Limited 1994 Uric acid degrading enzymes, urate oxidase and allantoinase, are associated with different subcellular organelles in frog liver and kidney Nobuteru Usuda1,*, Sueko Hayashi1,†, Satoko Fujiwara2, Tomoo Noguchi2, Tetsuji Nagata3, M. Sambasiva Rao1, Keith Alvares1, Janardan K. Reddy1 and Anjana V. Yeldandi1,‡ 1Department of Pathology, Northwestern University Medical School, Chicago, Illinois 60611, USA 2Department of Biochemistry, Kyushu Dental College, Kokura, Kitakyushu 803, Japan 3Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, Shinshu University School of Medicine, Matsumoto 390, Japan *Present address: Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, Shinshu University School of Medicine, Matsumoto 390, Japan †Present address: Kyushu Dental College, Kokura, Kitakyushu 803, Japan ‡Author for correspondence SUMMARY On the basis of differential and density gradient centrifu- found to be the exclusive site of urate oxidase localization. gation studies, the site of the uric acid degrading enzymes, Allantoinase was detected within mitochondria, but not in urate oxidase and allantoinase, in amphibia was previously peroxisomes of hepatocytes or proximal tubular epithe- assigned to the hepatic peroxisomes. Using specific anti- lium. No allantoinase was detected in the mitochondria of bodies against frog urate oxidase and allantoinase, we have nonhepatic parenchymal cells in liver and of the cells lining undertaken an immunocytochemical study of the localiza- the distal convoluted tubules of the kidney. These results tion of these two proteins in frog liver and kidney, and demonstrate that, unlike rat kidney peroxisomes which demonstrate that whereas urate oxidase is present in per- lack urate oxidase, peroxisomes of frog kidney contain this oxisomes, allantoinase is localized in mitochondria. -

Purine Metabolism

PURINE METABOLISM CH O-P CH O-P CH O-P CH O-P NH NH NH NH 2 2 2 2 H C 2 H C HC O H O H O O NHCOCH NH 2 2 H2C NH2 2 2 Formyl- CHO CHO CH Glutamine Glutamate OC OC C C H H H H H H Glycine H H or NH H folate NH ADP N H OH H H H H 4 ATP Pi HN = NH ADP ATP AMP O-P-O-P HO H ATP ADP+P Gln H O Glu H N 2 PP H folate 2 ATP Pi 2 OH OH OH OH OH OH OH OH Ribose-P 4 Ribose-P Ribose-P Ribose-P 5-P-ribose 5-P-ribosyl- 5-P-Ribosylamine N1-(5-P-ribosyl)glycinamide N2-formyl-N1-(5-P-ribosyl) 2-(formamido)-N1- 5-amino-1-(P-ribosyl)- 2.7.6.1 pyrophosphate 2.4.2.14 6.3.4.13 2.1.2.2 6.3.5.3 (5-P-ribosyl)acetamidine 6.3.3.1 ADP GDP AMP GTP glycinamide - imidazole (PRPP) GDP ADP ATP ATPGMP -OOCCHCH COO- -OOCCHCH COO- 2 2 O O O CO NH - - - - 2 OOCCHCH COO C HN CO OOCCHCH2COO - C NH 2 C N C NH NH NH OOC 4.1.1.21 N 2 HN H N + NH N C C H2N C 2 C C Aspartate NH3 C CH GDP CH CH Formyl- CH CH Aspartate CH ADP HC C HC C OHC C H4folate C C Pi N Pi N H O N N N ADP C N GTP N 2 N H N H N N H4folate 2 Fumarate 2 P H N H i ATP 2 Ribose-P Ribose-P Ribose-P Ribose-P Ribose-P Ribose-P CLE 4.3.2.2 CY 4.3.2.2 E Adenylosuccinate Inosine- 5-formamido-1-(5-P-ribosyl)- 5-amino-1-(5-P-ribosyl)- 5-amino-1-(5-P-ribosyl-) 5-amino-1-(5-P-ribosyl) ID P 2.1.2.3 T 3.5.4.10 6.3.2.6 O imidazole-4-carboxamide imidazole-4-(N)-[1,2-dicarboxy- imidazole-4-carboxylate E IMP imidazole-4-carboxamide L ethyl]-carboxamide C U N E RNA N I 2.7.7.6 2.7.7.6 R Fumarate TCA U CYCLE P RNA ACIDS RNA RNA n NUCLEIC n n+1 RNAn+1 DNA NH2 NH C 2.7.7.7 2.7.7.7 2 N O C N N C N C CH DNA DNA DNA C N CH HC C n n+1 DNAn+1 -

Chinese Multidisciplinary Expert Consensus on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Hyperuricemia and Related Diseases

Expert Consensus Chinese Multidisciplinary Expert Consensus on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Hyperuricemia and Related Diseases Multidisciplinary Expert Task Force on Hyperuricemia and Related Diseases Key words: Consensus; Gout; Hyperuricemia; Recommendation; Uric Acid INTRODUCTION factors. A nationwide epidemiological survey of HUA is still lacking in China. The data from different regions at The prevalence of hyperuricemia (HUA) has increased various times have shown an overall increasing prevalence in China in the recent years in relation to socioeconomic of HUA in the recent years.[1,2] Epidemiological studies have developments and changing lifestyles and diets, with a trend shown that the prevalence of HUA varies greatly among toward onset at younger age. HUA has become the second geographical regions in China over the previous 10 years, most common metabolic disease after diabetes mellitus. ranging from 5.46% to 19.30%, specifically 9.2–26.2% Like gout, HUA is also associated with the occurrence and in males and 0.7–10.5% in females.[3‑7] The prevalence progression of disorders of the urinary, endocrine, metabolic, of gout varies from 0.86% to 2.20% among geographical cardio‑cerebrovascular, and other systems. Different expert regions in China, specifically 1.42–3.58% in males and panels have developed guidelines and consensuses on 0.28–0.90% in females.[1,3,8] The prevalence of both HUA HUA and gout in their respective fields. This consensus and gout increases with age and is more prevalent in males has been formulated in accordance with a systematic than that in females, in cities than that in rural areas, and medical model by a task force including rheumatologists, in coastal than that in inland areas.[9] nephrologists, endocrinologists, cardiologists, neurologists, urologists, and experts in traditional Chinese medicine.