2020 Digest Chapter 18

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keesep Starts Sunday, Right on Time

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 13, 2020 KEESEP STARTS SUNDAY, BREEDERS= CUP BACK TO KEENELAND IN 2022, PURSES MAINTAINED IN 2020 RIGHT ON TIME The Breeders= Cup will return to Keeneland Race Course in Lexington, Ky. as the host site for the 2022 Breeders= Cup World Championships, the Breeders= Cup announced Saturday. Keeneland, which is also scheduled to host this year=s World Championships Nov. 6-7, will hold the 39th Breeders= Cup Nov. 4-5, 2022. It will be the third time the Breeders= Cup has been held at Keeneland since 2015. Del Mar will remain the host of the 2021 event. The announcement of Keeneland as host of the 2022 championships was made in conjunction with two other pieces of news: first, attendance at this year=s event will be limited to the connections of race participants and essential staff, and without fans on-site, due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Cont. p6 Keeneland sales grounds | Keeneland photo IN TDN EUROPE TODAY by Jessica Martini MAGICAL TAKES CHAMPION THRILLER LEXINGTON, KY - While the coronavirus pandemic wreaked Magical (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}) turned the tables on Ghaiyyath havoc with sales across the globe from March through August, (Ire) (Dubawi {Ire}) to record back-to-back wins in the G1 Irish the calendar will return to some semblance of normalcy when Champion S. the Keeneland September Yearling Sale kicks off right on Click or tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. schedule in Lexington Sunday at noon. ASo many sales companies in the Northern Hemisphere have had to rearrange some things, but we have been very fortunate that the September sale is taking place in September at Keeneland,@ said Keeneland=s Director of Sales Operations Geoffrey Russell. -

The United Nations Human Rights Council: Background and Policy Issues

The United Nations Human Rights Council: Background and Policy Issues Luisa Blanchfield Specialist in International Relations Michael A. Weber Analyst in Foreign Affairs Updated April 20, 2020 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov RL33608 SUMMARY RL33608 The United Nations Human Rights Council: April 20, 2020 Background and Policy Issues Luisa Blanchfield Over the years, many Members of Congress have demonstrated an ongoing interest in the role Specialist in International and effectiveness of the United Nations (U.N.) Human Rights Council (the Council). The Relations Council is the primary intergovernmental body mandated with addressing human rights on a [email protected] global level. The United States was a member of the Council for two three-year terms during the Michael A. Weber Obama Administration, and a third term during the first part of the Trump Administration. In Analyst in Foreign Affairs June 2018, the Trump Administration withdrew from the Council, noting concerns with the [email protected] Council’s focus on Israel, overall ineffectiveness in addressing human rights issues, and lack of reform. Some of the Council’s activities are suspended or being implemented remotely due to For a copy of the full report, concerns about COVID-19. please call 7-.... or visit www.crs.gov. Background The U.N. General Assembly established the Human Rights Council in 2006 to replace the Commission on Human Rights, which was criticized for its ineffectiveness in addressing human rights abuses and for the number of widely perceived human rights abusers that served as its members. Since 2006, many governments and observers have expressed serious concerns with the Council’s disproportionate attention to Israel and apparent lack of attention to other pressing human rights situations. -

Iraq: Summary of U.S

Order Code RL31763 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Iraq: Summary of U.S. Forces Updated March 14, 2005 Linwood B. Carter Information Research Specialist Knowledge Services Group Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Iraq: Summary of U.S. Forces Summary This report provides a summary estimate of military forces that have reportedly been deployed to and subsequently withdrawn from the U.S. Central Command (USCENTCOM) Area of Responsibility (AOR), popularly called the Persian Gulf region, to support Operation Iraqi Freedom. For background information on the AOR, see [http://www.centcom.mil/aboutus/aor.htm]. Geographically, the USCENTCOM AOR stretches from the Horn of Africa to Central Asia. The information about military units that have been deployed and withdrawn is based on both official government public statements and estimates identified in selected news accounts. The statistics have been assembled from both Department of Defense (DOD) sources and open-source press reports. However, due to concerns about operational security, DOD is not routinely reporting the composition, size, or destination of units and military forces being deployed to the Persian Gulf. Consequently, not all has been officially confirmed. For further reading, see CRS Report RL31701, Iraq: U.S. Military Operations. This report will be updated as the situation continues to develop. Contents U.S. Forces.......................................................1 Military Units: Deployed/En Route/On Deployment Alert ..............1 -

D:\AN12034\Wholechapters\AN Chaps PDF.Vp

CHAPTER 1 MISSION AND HISTORY OF NAVAL AVIATION INTRODUCTION in maintaining command of the seas. Accomplishing this task takes five basic operations: Today's naval aircraft have come a long way from the Wright Brothers' flying machine. These modern 1. Eyes and ears of the fleet. Naval aviation has and complex aircraft require a maintenance team that is over-the-horizon surveillance equipment that provides far superior to those of the past. You have now joined vital information to our task force operation. this proud team. 2. Protection against submarine attack. Anti- You, the Airman Apprentice, will get a basic submarine warfare operations go on continuously for introduction to naval aviation from this training the task force and along our country's shoreline. This manual. In the Airman manual, you will learn about the type of mission includes hunter/killer operations to be history and organization of naval aviation; the design of sure of task force protection and to keep our coastal an aircraft, its systems, line operations, and support waterways safe. equipment requirements; and aviation safety, rescue, 3. Aid and support operations during amphibious crash, and fire fighting. landings. From the beginning to the end of the In this chapter, you will read about some of the operations, support occurs with a variety of firepower. historic events of naval aviation. Also, you will be Providing air cover and support is an important introduced to the Airman rate and different aviation function of naval aviation in modern, technical warfare. ratings in the Navy. You will find out about your duties 4. -

The UN Security Council and Climate Change

Research Report The UN Security Council and Climate Change Dead trees form an eerie tableau Introduction on the shores of Maubara Lake in Timor-Leste. UN Photo/Martine Perret At the outset of the Security Council’s 23 Feb- particular the major carbon-emitting states, will ruary 2021 open debate on climate and security, show the level of commitment needed to reduce world-renowned naturalist David Attenborough carbon emissions enough to stave off the more dire delivered a video message urging global coopera- predictions of climate modellers. tion to tackle the climate crisis. “If we continue on While climate mitigation and adaptation 2021, No. #2 21 June 2021 our current path, we will face the collapse of every- measures are within the purview of the UN thing that gives us our security—food production; Framework Convention on Climate Change This report is available online at securitycouncilreport.org. access to fresh water; habitable, ambient tempera- (UNFCCC) and contributions to such measures tures; and ocean food chains”, he said. Later, he are outlined in the Paris Agreement, many Secu- For daily insights by SCR on evolving Security Council actions please added, “Please make no mistake. Climate change rity Council members view climate change as a subscribe to our “What’s In Blue” series at securitycouncilreport.org is the biggest threat to security that humans have security threat worthy of the Council’s attention. or follow @SCRtweets on Twitter. ever faced.” Such warnings have become common. Other members do not. One of the difficulties in And while the magnitude of this challenge is widely considering whether or not the Council should accepted, it is not clear if the global community, in play a role (and a theme of this report) is that Security Council Report Research Report June 2021 securitycouncilreport.org 1 1 Introduction Introduction 2 The Climate-Security Conundrum 4 The UN Charter and Security there are different interpretations of what is on Climate and Security, among other initia- Council Practice appropriate for the Security Council to do tives. -

The Demand for Responsiveness in Past U.S. Military Operations for More Information on This Publication, Visit

C O R P O R A T I O N STACIE L. PETTYJOHN The Demand for Responsiveness in Past U.S. Military Operations For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR4280 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0657-6 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. 2021 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: U.S. Air Force/Airman 1st Class Gerald R. Willis. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface The Department of Defense (DoD) is entering a period of great power competition at the same time that it is facing a difficult budget environment. -

Confronting the Rise in Anti-Semitic Domestic Terrorism

CONFRONTING THE RISE IN ANTI-SEMITIC DOMESTIC TERRORISM HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE AND COUNTERTERRORISM OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JANUARY 15, 2020 Serial No. 116–58 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 41–310 PDF WASHINGTON : 2020 VerDate Mar 15 2010 09:11 Sep 22, 2020 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\116TH\20IC0115\41310.TXT HEATH Congress.#13 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi, Chairman SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas MIKE ROGERS, Alabama JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island PETER T. KING, New York CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas DONALD M. PAYNE, JR., New Jersey JOHN KATKO, New York KATHLEEN M. RICE, New York MARK WALKER, North Carolina J. LUIS CORREA, California CLAY HIGGINS, Louisiana XOCHITL TORRES SMALL, New Mexico DEBBIE LESKO, Arizona MAX ROSE, New York MARK GREEN, Tennessee LAUREN UNDERWOOD, Illinois VAN TAYLOR, Texas ELISSA SLOTKIN, Michigan JOHN JOYCE, Pennsylvania EMANUEL CLEAVER, Missouri DAN CRENSHAW, Texas AL GREEN, Texas MICHAEL GUEST, Mississippi YVETTE D. CLARKE, New York DAN BISHOP, North Carolina DINA TITUS, Nevada BONNIE WATSON COLEMAN, New Jersey NANETTE DIAZ BARRAGA´ N, California VAL BUTLER DEMINGS, Florida HOPE GOINS, Staff Director CHRIS VIESON, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE AND COUNTERTERRORISM MAX ROSE, New York, Chairman SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas MARK WALKER, North Carolina, Ranking JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island Member ELISSA SLOTKIN, Michigan PETER T. KING, New York BENNIE G. -

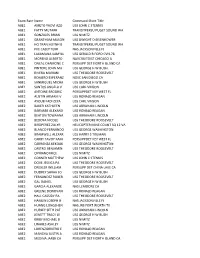

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE1 FATTY MUTARR TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 GONZALES BRIAN USS NIMITZ ABE1 GRANTHAM MASON USS DWIGHT D EISENHOWER ABE1 HO TRAN HUYNH B TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 IVIE CASEY TERR NAS JACKSONVILLE FL ABE1 LAXAMANA KAMYLL USS GERALD R FORD CVN-78 ABE1 MORENO ALBERTO NAVCRUITDIST CHICAGO IL ABE1 ONEAL CHAMONE C PERSUPP DET NORTH ISLAND CA ABE1 PINTORE JOHN MA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 RIVERA MARIANI USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE1 ROMERO ESPERANZ NOSC SAN DIEGO CA ABE1 SANMIGUEL MICHA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 SANTOS ANGELA V USS CARL VINSON ABE2 ANTOINE BRODRIC PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 AUSTIN ARMANI V USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 AYOUB FADI ZEYA USS CARL VINSON ABE2 BAKER KATHLEEN USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BARNABE ALEXAND USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 BEATON TOWAANA USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BEDOYA NICOLE USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 BIRDPEREZ ZULYR HELICOPTER MINE COUNT SQ 12 VA ABE2 BLANCO FERNANDO USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 BRAMWELL ALEXAR USS HARRY S TRUMAN ABE2 CARBY TAVOY KAM PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 CARRANZA KEKOAK USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 CASTRO BENJAMIN USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 CIPRIANO IRICE USS NIMITZ ABE2 CONNER MATTHEW USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE2 DOVE JESSICA PA USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 DREXLER WILLIAM PERSUPP DET CHINA LAKE CA ABE2 DUDREY SARAH JO USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 FERNANDEZ ROBER USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 GAL DANIEL USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 GARCIA ALEXANDE NAS LEMOORE CA ABE2 GREENE DONOVAN USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 HALL CASSIDY RA USS THEODORE -

U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons Piracy

U.S. Naval War College U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons CIWAG Case Studies 8-2012 Piracy Martin Murphy Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/ciwag-case-studies Recommended Citation Murphy, Martin, "MIWS_05 - Piracy" (2012). CIWAG Maritime Irregular Warfare Studies. 5. https://digital- commons.usnwc.edu/ciwag-case-studies/11 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in CIWAG Case Studies by an authorized administrator of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Draft as of 121916 ARF R W ARE LA a U nd G A E R R M R I E D n o G R R E O T U N P E S C U N E IT EG ED L S OL TA R C TES NAVAL WA Piracy Dr. Martin Murphy United States Naval War College Newport, Rhode Island Piracy Martin Murphy Center on Irregular Warfare & Armed Groups (CIWAG) US Naval War College, Newport, RI [email protected] Murphy: Piracy CIWAG Case Studies Water Wars: The Brahmaputra River and Sino-Indian Relations— Mark Christopher Taliban Networks in Afghanistan—Antonio Giustozzi Operationalizing Intelligence Dominance—Roy Godson El Salvador in the 1980s: War by Other Means—Donald R. Hamilton Operational Strategies to Counter IED Threat in Iraq—Michael Iacobucci Sovereign Wealth Funds as Tools of National Strategy: Singapore’s Approach—Devadas Krishnadas Varieties of Insurgency and Counterinsurgency in Iraq, 2003-2009— Jon Lindsay and Roger Petersen Piracy—Martin Murphy An Operator’s Guide to Human Terrain Teams—Norman Nigh Revolutionary Risks: Cyber Technology and Threats in the 2011 Libyan Revolution—John Scott-Railton Organizational Learning and the Marine Corps: The Counterinsurgency Campaign in Iraq—Richard Shultz Reading the Tea Leaves: Proto-Insurgency in Honduras—John D. -

Binding Political Commitments

BINDING POLITICAL COMMITMENTS Farshad Ghodoosi* INTRODUCTION The recent unprecedented rift, in particular between the US and its Euro- pean allies, in the Security Council vis-à-vis the Iran deal can be seen as the culmination of the American First policy of recent years. The United States de- cided to ignore the UN Security Council’s overwhelming rejection on its move to snap back the UN sanctions on Iran and proceeded unilaterally with the UN sanctions.1 This means that the United States plans to enforce UN Security Coun- cil resolutions that other members of the same council believe are terminated.2 Relatedly and more importantly, the stand-off can also be seen as the culmination of years of framing international law away from basic notions of law and though notions of soft law and political commitments. Contrary to the US position, which is partly premised on the nonbinding characterization of the deal, this short piece argues that the deal is binding while outlining the inadequacy of the pre- vailing approaches in framing international commitments.3 On August 20, 2020 the US submitted its notification to the UN Secretary General and the Security Council President that the US is initiating the snap back 4 mechanism of the Iran deal due to “Iran’s significant non-performance.” This * Assistant Professor, California State University, Northridge, Nazarian College of Business & Econom- ics, Department of Business Law, JSD, LL.M, Yale Law School, LLM in Business Law, U.C. Berkeley. 1. Compare UN Security Council rejects US demand to 'snapback' sanctions on Iran, DEUTSCHE WELLE, https://www.dw.com/en/un-security-council-rejects-us-demand-to-snapback-sanctions-on-iran/a-54697653 [https://perma.cc/JM6Z-KCRG] (last visited Oct. -

Speakers BLUEGRASS REGION's FEDERAL POLICY FORUM

Bluegrass Region’s Federal Policy Forum Presented By A NiSource Company September 8-9, 2020 Agenda A NiSource Company TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 8, 2020 EVENT NOTE: Those who registered for the Federal Policy Forum will be e-mailed a Zoom link in advance for each day of the virtual event. Participants will use one link to access all sessions on September 8th, and a different link for sessions on September 9th. 9:45 a.m. Welcome Remarks The opening session offers a brief overview of the Central Kentucky Policy Group’s key priorities for federal advocacy. Bob Quick Kimra Cole President & CEO President & Chief Operating Officer Commerce Lexington Inc. Columbia Gas of Kentucky 10:00 a.m. Kentuckians in Washington Spotlight Kelly Craft, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Join the conversation with Ambassador Craft to learn about her unique role in rep- resenting America at the United Nations and the impact of federal policy on the global economy and national security. BREAK 11:30 a.m. Federal Business Advocacy Update Neil Bradley Executive Vice President & Chief Policy Officer U.S. Chamber of Commerce Neil Bradley provides a recap of federal issues important to the business commu- nity and analysis of the situation in Congress as negotiations continue over the next federal relief package. FEDERAL POLICY FORUM - 3 TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 8, 2020 BREAK 1:00 p.m. Congressional Member Update Congressman Andy Barr (KY-6) As a member of the Financial Services Committee, Rep. Barr has been a tire- less advocate for businesses seeking financial relief during the pandemic and a liaison between businesses and key officials at the SBA, Treasury and Federal Reserve. -

Women Appointed to Presidential Cabinets

WOMEN APPOINTED TO PRESIDENTIAL CABINETS Eleven women have been confirmed to serve in cabinet (6) and cabinet level (5) positions in the Biden administration.1 A total of 64 women have held a total of 72 such positions in presidential administrations, with eight women serving in two different posts. (These figures do not include acting officials.) Among the 64 women, 41 were appointed by Democratic presidents and 23 by Republican presidents. Only 12 U.S presidents (5D, 7R) have appointed women to cabinet or cabinet-level positions since the first woman was appointed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933.2 Party breakdown of women appointed to Presidential Cabinets: 41D 23R Cabinet or Cabinet-level Firsts: First Woman First Black Woman First Latina First Asian Pacific First Native Appointed Appointed Appointed Islander Woman American Woman Appointed Appointed Frances Perkins Patricia Roberts Aída Álvarez Elaine Chao Debra Haaland Secretary of Labor Harris Administrator, Secretary of Labor Secretary of the 1933 (Roosevelt) Secretary of Small Business 2001 (G.W. Bush) Interior Housing and Urban Administration 2021 (Biden) Development 1997 (Clinton) 1977 (Carter) To date, 27 cabinet or cabinet-level posts have been filled by women. Cabinet and cabinet-level positions vary by presidential administration. Our final authority for designating cabinet or cabinet-level in an 1 This does not include Shalanda Young, who currently serves as Acting Director of the Office of Management and Budget. 2 In addition, although President Truman did not appoint any women, Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, a holdover from the Roosevelt administration, served in his cabinet. © COPYRIGHT 2021 Center for American Women and Politic, Eagleton Institute of Politics, Rutgers University 4/6/2021 administration is that president's official library.