Australian Government Department of the Environment and Energy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native Title in the News – November & December 2000

We are busily completing the final production of the proceedings from last year’s Native Title Representative Bodies Legal Conference, held in Melbourne in April 2000. Bryan Keon-Cohen QC has been working furiously to edit the papers, a selection of which will be published in the book with a great deal of additional material to be included on an accompanying CD. The result will be an exciting and very important publication. So, look out for Native Title in the New Millennium. Hot on the heels of the proceedings we are working on the next NTRB Legal Conference which will be a celebration of the 20 year Anniversary of the Townsville conference that initiated the Mabo litigation. The conference will be held in Townsville on the 28-30 August 2001. We will keep you posted on developments with the organisation of the event. NATIVE TITLE IN THE NEWS – NOVEMBER & DECEMBER 2000 New South Wales Land holders and other interest holders affected by the Muthi Muthi native title application over 23,829 square kilometres in south western New South Wales have been invited by the National Native Title Tribunal to register for mediation talks. The application covers land in Balranald Shire bounded by Euston, the Murray and Edward Rivers to Moolpa, Maude, Booligal, Willandra Creek and Mungo National Park and excludes private freehold land. (NNTT Media Release, 13 Dec) The National Native Title Tribunal has advertised five native title applications in western New South Wales inviting interest holders to register as parties to the mediation proceedings. The applications in the Balranald, Bourke, Broken Hill, Central Darling, Cobar, Wentworth and Unincorporated Area do not cover any private freehold land. -

Ken Hill and Darling River Action Group Inc and the Broken Hill Menindee Lakes We Want Action Facebook Group

R. A .G TO THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN MURRAY DARLING BASIN ROYAL COMMISSION SUBMISSION BY: The Broken Hill and Darling River Action Group Inc and the Broken Hill Menindee Lakes We Want Action Facebook Group. With the permission of the Executive and Members of these Groups. Prepared by: Mark Hutton on behalf of the Broken Hill and Darling River Action Group Inc and the Broken Hill Menindee Lakes We Want Action Facebook Group. Chairman of the Broken Hill and Darling River Action Group and Co Administrator of the Broken Hill Menindee Lakes We Want Action Facebook Group Mark Hutton NSW Date: 20/04/2018 Index The Effect The Cause The New Broken Hill to Wentworth Water Supply Pipeline Environmental health Floodplain Harvesting The current state of the Darling River 2007 state of the Darling Report Water account 2008/2009 – Murray Darling Basin Plan The effect on our communities The effect on our environment The effect on Indigenous Tribes of the Darling Background Our Proposal Climate Change and Irrigation Extractions – Reduced Flow Suggestions for Improvements Conclusion References (Fig 1) The Darling River How the Darling River and Menindee Lakes affect the Plan and South Australia The Effect The flows along the Darling River and into the Menindee Lakes has a marked effect on the amount of water that flows into the Lower Murray and South Australia annually. Alought the percentage may seem small as an average (Approx. 17% per annum) large flows have at times contributed markedly in times when the Lower Murray River had periods of low or no flow. This was especially evident during the Millennium Drought when a large flow was shepherded through to the Lower Lakes and Coorong thereby averting what would have been a natural disaster and the possibility of Adelaide running out of water. -

Industry & Investment NSW – Fisheries Research Report Series

Industry & Investment NSW – Fisheries Research Report Series: 28 Lower Murray-Darling Catchment Action Plan: Fish Community Monitoring Report Card for 2009/10 by Dean Gilligan November 2010 ISSN 1837-2120 Industry & Investment NSW – Fisheries Research Report Series This series presents scientific and technical information on general fisheries research and the documents in the series are intended to be progress reports on ongoing investigations. Titles in this series may be cited as publications, with the correct citation on the front cover. Fisheries Research in New South Wales Fisheries research activities in the NSW Department of Primary Industries are based at various centres throughout the state. The studies conducted cover commercial and recreational fisheries and aquaculture, and conservation issues in coastal and riverine areas. The major role of the research is to provide information upon which relevant fisheries management policies and strategies are developed, monitored and assessed in terms of the Department’s obligations under the NSW Fisheries Management Act, 1994. Title: Lower Murray-Darling Catchment Action Plan: Fish Community Monitoring Report Card for 2009/10 Authors: Dean Gilligan Published By: Industry & Investment NSW (now incorporating NSW Department of Primary Industries) Postal Address: PO Box 21, Cronulla, NSW, 2230 Internet: www.dpi.nsw.gov.au © Industry & Investment NSW (Industry & Investment NSW) This work is copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this reproduction may be reproduced by any process, electronic or otherwise, without the specific written permission of the copyright owners. Neither may information be stored electronically in any form whatsoever without such permission. DISCLAIMER The publishers do not warrant that the information in this report is free from errors or omissions. -

Environmental Water Management Plan for the Murray River from Lock 6 – Lock 10

Environmental Water Management Plan for the Murray River from Lock 6 – Lock 10 Environmental Water Management Plan for the Murray River from Lock 6 to Lock 10 Environmental Water Management Plan for the Murray River from Lock 6 – Lock 10 DOCUMENT CONTROL Revision and Distribution Version no. Description Issued to Issue date Environmental Water Management 1 Plan for the Murray River from Lock 6 Jane White 9 January 2015 to Lock 10 - System Characterisation 2 Review Simone Wilkie, Riverness 27 April 2015 3 Final Draft Jane White 30 April 2015 Citation Ecological Associates (2015). Environmental Water Management Plan for the Murray River from Lock 6 to Lock 10 - System Characterisation. Ecological Associates report AL043-1-A prepared for Mallee Catchment Management Authority, Irymple. Contact For queries regarding this document, please contact: Louise Chapman [email protected] Waterways Coordinator Mallee Catchment Management Authority This publication may be of assistance to you but the Mallee Catchment Management Authority and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purpose and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence that may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Environmental Water Management Plan for the Murray River from Lock 6 – Lock 10 Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................i -

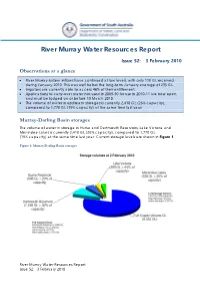

River Murray Water Resources Report

River Murray Water Resources Report Issue 52: 3 February 2010 Observations at a glance River Murray system inflows have continued at low levels, with only 110 GL received during January 2010. This was well below the long-term January average of 235 GL. Irrigators are currently able to access 48% of their entitlement. Applications to carry-over water not used in 2009-10 for use in 2010-11 are now open, and must be lodged on or before 19 March 2010. The volume of water in upstream storages is currently 2,418 GL (26% capacity), compared to 1,770 GL (19% capacity) at the same time last year. Murray-Darling Basin storages The volume of water in storage in Hume and Dartmouth Reservoirs, Lake Victoria and Menindee Lakes is currently 2,418 GL (26% capacity), compared to 1,770 GL (19% capacity) at the same time last year. Current storage levels are shown in Figure 1. Figure 1: Murray-Darling Basin storages River Murray Water Resources Report Issue 52: 3 February 2010 Of the above volume, the amount of water currently held within the main Murray-Darling Basin Authority-operated storages (Hume, Dartmouth and Lake Victoria) is currently 2,080 GL or 27% capacity. The volume of water held in Menindee Lakes has been increasing due to improved flows along the Darling River and is currently 338 GL or 20% capacity. Releases will continue from Hume and Dartmouth Reservoirs over the coming months to assist in supplying downstream requirements, including irrigation diversions. Rainfall and River Murray inflows Southern Murray-Darling Basin River Murray system inflows have continued at low levels. -

Environmental Flows in the Darling River to Support Native Fish Populations 2016–17

Environmental flows in the Darling River to support native fish populations 2016–17. 1 Environmental flows in the Darling River to support native fish populations 2016–17 Citation: Sharpe, C. and Stuart, I. (2018). Environmental flows in the Darling River to support native fish populations. CPS Enviro report to The Commonwealth Environmental Water Office. Acknowledgements: This project was funded by the Commonwealth Environmental Water Office. From NSW OEH; Paula D’Santos, Sascha Healy and Paul Childs provided tireless leadership in flow planning and coordination to the lower Darling River and Great Darling Anabranch throughout 2016–17 to promote the maintenance and recovery of fish populations in the Darling River and Southern-Connected Basin. From NSW DPI Fisheries; Iain Ellis provided expert ecological input and support to flow planning, agency and community engagement of the project findings. From CEWO Alana Wilkes, Irene Wegener, Hilton Taylor, Hilary Johnson, and Sean Kelly and from the Murray–Darling Basin Authority, Adam Sluggett, Adam McLean, Kerry Greenwood, John Waterworth and Tristan Skinner provided operational guidelines for hydrograph development and delivery to the lower Darling River and Great Darling Anabranch. From CPS Enviro, Sheridan Stephens for project administration and Steve Campbell-Brown and Mark Henderson for technical support in field sampling the Darling River (Walgett-Wentworth), Great Darling Anabranch and in the Menindee Lakes. We thank landholders along the Darling River and Anabranch for access through their properties. This work was conducted under NSW Fisheries Permit P12/0004 and Griffith University ACEC ENV0414AEC. Disclaimer: The results and comments contained in this report have been provided on the basis that the recipient assumes the sole responsibility for the interpretation and application of them. -

Minerals Council of Australia

MINERALS COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA SUBMISSION TO THE SENATE INQUIRY INTO THE IMPACT OF MINING OPERATIONS ON THE ENVIRONMENTAL VALUES OF THE MURRAY-DARLING BASIN 13 OCTOBER 2009 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Members of the Minerals Council of Australia (MCA), representing over 85% of minerals production in Australia, have a long-standing commitment to sustainable development including the responsible stewardship of natural resources. Minerals operations contribute significantly to Australia‘s economic prosperity, including: 8% national GDP; 42% of goods and services exports; and tax and royalties in 2007/8 of $13.04 billion and in 2008/9 of $21.019 billion. This economic contribution is delivered from a limited natural resources base, including a landscape footprint of just 0.3% and a water usage of 3% of national consumptive use. Much of the water used by minerals operations is not fit for other purposes (e.g. being hyper-saline) and is recycled internally to minimise freshwater input requirements. Mining in the Murray-Darling Basin accounts for approximately 5% of total national minerals production. The Basin accounts for just over 8% of total minerals industry employees, approximately 10,000 employees. Currently 35 minerals operations are in the Basin, with few projected significant developments beyond pre-feasibility stage. Environmental Values in the Murray-Darling Basin This Senate inquiry is examining the impact of mining operations on environmental values in the Murray-Darling Basin. The Murray-Darling Basin Authority (MDBA) identifies the following key values and functions of the Basin: high environmental value assets (biodiversity, recreational, amenity); water supply and distribution (human water consumption, irrigation, navigation); and agricultural production (irrigated agriculture). -

The Murray-Lower Darling Catchment and the Long Term Water Plan Explained

DEPARTMENT OF PLANNING, INDUSTRY AND ENVIRONMENT The Murray-Lower Darling catchment and the Long Term Water Plan explained 1 © 2019 State of NSW and Department of Planning Industry and Environment With the exception of photographs, the State of NSW and Department of Planning Industry and Environment are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. The Department of Planning Industry and Environment (DPIE) has compiled this report in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. DPIE shall not be liable for any damage which may occur to any person or organisation taking action or not on the basis of this publication. Readers should seek appropriate advice when applying the information to their specific needs. All content in this publication is owned by DPIE and is protected by Crown Copyright, unless credited otherwise. It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0), subject to the exemptions contained in the licence. The legal code for the licence is available at Creative Commons. DPIE asserts the right to be attributed as author of the original material in the following manner: © State of New South Wales and Department of Planning Industry -

Sun R a Y Sia R Eg Io

swimming spots, walks and drives. drives. and drives. walks and spots, walks drives. and spots, swimming walks swimming spots, swimming and and fishing and fishing beaches, and as well beaches, fishing as as well as facilities beaches, as picnic well facilities as and picnic facilities and picnic and camping camping of camping plenty of e r a e r plenty camping e The r a of e. r e r hi The plenty e. e r r canoe hi a e r and The canoe e. boat r hi and boat canoe and boat November 2015 2015 November November 2015 November cruises, cruises, river cruises, riding, river bike cruises, riding, tours, river bike drives, tours, riding, tours, bike drives, tours, guided tours, drives, guided tours, guided www.mda.asn.au www.mda.asn.au www.mda.asn.au self- self- include They include self- close. They up include close. up They onment r envi close. onment r up envi unique onment r unique envi unique For more information: 03 5480 3805 5480 3805 03 5480 03 3805 information: 5480 03 more information: For more For information: more For egion’s egion’s r the egion’s r the experience egion’s r to the experience ways to many ways e r experience a to e r many e The r a ways e r The many e r a e r The Murray Darling Association Inc. Inc. Association Inc. Association Darling Darling Murray Association Murray Darling Murray The Murray Valley Trail is an initiative of the the of the of initiative an the is initiative of Trail an is initiative Trail Valley an is Valley Murray Trail The Murray Valley The Murray The UP CLOSE AND PERSONAL AND PERSONAL AND CLOSE PERSONAL UP CLOSE AND UP CLOSE UP Basin Authority. -

Connecting Rivers to Recover Native Fish Communities

1 Towards a southern connected basin flow plan: connecting rivers to recover native fish communities Ivor Stuart and Clayton Sharpe December 2017 Kingfisher Research and CPS Enviro 2 Citation: Stuart, I. and Sharpe, C. (2017). Towards a southern connected basin flow plan: connecting rivers to recover native fish communities. Kingfisher Research and CPS Enviro report to the Murray-Darling Basin Authority. Acknowledgements: This document has benefited by discussions with many riparian landholders, scientists and managers. Specifically we thank: Kat Cheshire (NSW DPI), Sam Davis (NSW DPI), Iain Ellis (NSW DPI), Tony Townsend (NSW DPI), Jarod Lyon (ARI), Martin Mallen-Cooper (Fishway Consulting Services), Wayne Smith (‘Karoola’ Station, Darling River) and Brenton Zampatti (SARDI). We appreciate help from Brayden Dykes (MDBA) who drafted many of the graphics used. Our thanks to Heleena Bamford and Stuart Little from the Murray-Darling Basin Authority for funding and supporting this work. Disclaimer: This publication may be of assistance to you but CPS Enviro Pty Ltd and Kingfisher Research Pty Ltd and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. This project was funded by the Murray-Darling Basin Authority. The contents of this publication do not purport to represent the position of the copyright holders or the Murray-Darling Basin Authority in any way and are presented for the purpose of informing and stimulating discussion for improved management of Basin's natural resources. -

Murray-Darling Basin Annual Report 2014-15

ANNUAL REPORT 2015–16 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF THE TRADITIONAL OWNERS OF THE MURRAY–DARLING BASIN The Murray–Darling Basin Authority acknowledges and 'The environment that pays respect to the Traditional Aboriginal people know Owners, and their Nations, as Country has not been of the Murray–Darling Basin, allowed to have a voice in who have a deep cultural, contemporary Australia. social, environmental, spiritual Aboriginal First Nations have and economic connection to been listening to Country for their lands and waters. The many thousands of years MDBA understands the need and can speak for Country so for recognition of Traditional that others can know what Owner knowledge and cultural values in natural resource Country needs. Through the management associated with the basin. Murray Lower Darling Rivers Indigenous Nations and the The approach of Traditional Owners to caring for the Northern Basin Aboriginal natural landscape, including water, can be expressed in Nations the voice of Country the words of Darren Perry (Chair of the Murray Lower Darling Rivers Indigenous Nations) can be heard by all.' BARAPA BARAPA BARKINDJI (PAAKANTYI) NARI NARI NGARRINDJERI BARUNGGAM BIDJARA NGEMBA NGINTAIT BIGAMBUL BUDJITI NGIYAMPAA NYERI NYERI DHUDHUROA DJA DJA WURRUNG TATTI TATTI TAUNGURUNG EUAHLAYI GAMILAROI WADI WADI WAILWAN GITHABUL GUNGGARI WAMBA WAMBA WAKKA WAKKA GWAMU (KOOMA) JAROWAIR WAYWURRU WEGI WEGI KAMBUWAL KUNJA WERGAIA WIRADJURI KWIAMBUL LATJI LATJI WOLGALU WOTJABALUK MALJANGAPA MANDANDANJI YAITMATHANG YITA YITA MARAURA MARDIGAN YORTA YORTA MURRAWARRI MUTTI MUTTI This report may contain photographs or quotes by Aboriginal people who have passed away. Most Aboriginal words can be spelt more than one way in English so spellings may vary in this publication. -

Darling Longitudinal Profile

1 120 140 160 0 20 40 60 80 0 0 Elevation (m) 0 Darling River flow into Barwon rivers Culgoa and Irrigation Area Bourke Bourke (F2) at Bourke Bourke Weir irrigation canal Orange Tree lagoon Darling River Weir 19A Salt Interception Scheme (10) ― Upper Darling Yanda Creek DARLING RIVER 2 0 0 Warrego River Darling River Weir 20A Louth (F2) at Louth Kerrigundi Creek Louth Weir (Darling River Weir 21) 4 0 Acres Billabong 0 Tilpa Weir (Darling River Weir 24) Tilpa Acres Billabong Talywalka Anabranch Lakes on Talywalka Creek (699 GL) ( F90) Wongalara Lake (233 GL) Poopelloe Lake (1,050 GL) Talywalka Creek 6 0 0 at BarrierHighwayWilcania Wilcannia (F3) at Wilcannia Lake Woytchugga Darling 120 100 2 4 6 8 0 0 0 0 0 Distance Elevation (m) R i v 8 8 0 0 e 0 0 r ( k P m r ) 1 o Darling River flows from Menidee lakesis2,049GL) f Lake Balaka i Coonalhugga Creek l e Lake Bijijie (total storagefor Basin Lake, Long Lake, Lake Are and Travellers Lake Lake Wetherell (262 GL) Lake Tandure Lake Tandou Menindee Main Weir Lake Pamamaroo (353 GL) Anabranch Lakes Menindee Lake Mindona Yartla Lake G Lake Menindee (729 GL) R Menindee Weir 32 (F40) at Menindee Weir Weir 32 E A Talywalka Anabranch Emu Lake T Travellers Lake D Lake Cawndilla (705 GL) Popio Lake A Coonalhugga Creek Popiltah Creek Popiltah Lake R 1,0 L 1,0 Nialia Lake I Yelta Lake N 0 0 1 G 0 Great Darling Anabranch 0 Nearie Lake 1014 Nitchie Lake 1018 A Warrawenia1030 Lake N Lake Milkengay 1040 A River Murray Anabranch (locality) B weir Toora Lake R 1070 A Yartla Lake N C H River System River System