Teeth Mammalian Teeth Differ from Teeth of Earlier Vertebrates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tooth Size Proportions Useful in Early Diagnosis

#63 Ortho-Tain, Inc. 1-800-541-6612 Tooth Size Proportions Useful In Early Diagnosis As the permanent incisors begin to erupt starting with the lower central, it becomes helpful to predict the sizes of the other upper and lower adult incisors to determine the required space necessary for straightness. Although there are variations in the mesio-distal widths of the teeth in any individual when proportions are used, the sizes of the unerupted permanent teeth can at least be fairly accurately pre-determined from the mesio-distal measurements obtained from the measurements of already erupted permanent teeth. As the mandibular permanent central breaks tissue, a mesio-distal measurement of the tooth is taken. The size of the lower adult lateral is obtained by adding 0.5 mm.. to the lower central size (see a). (a) Width of lower lateral = m-d width of lower central + 0.5 mm. The sizes of the upper incisors then become important as well. The upper permanent central is 3.25 mm.. wider than the lower central (see b). (b) Size of upper central = m-d width of lower central + 3.25 mm. The size of the upper lateral is 2.0 mm. smaller mesio-distally than the maxillary central (see c), and 1.25 mm. larger than the lower central (see d). (c) Size of upper lateral = m-d width of upper central - 2.0 mm. (d) Size of upper lateral = m-d width of lower central + 1.25 mm. The combined mesio-distal widths of the lower four adult incisors are four times the width of the mandibular central plus 1.0 mm. -

Specialized Stem Cell Niche Enables Repetitive Renewal of Alligator Teeth

Specialized stem cell niche enables repetitive renewal PNAS PLUS of alligator teeth Ping Wua, Xiaoshan Wua,b, Ting-Xin Jianga, Ruth M. Elseyc, Bradley L. Templed, Stephen J. Diverse, Travis C. Glennd, Kuo Yuanf, Min-Huey Cheng,h, Randall B. Widelitza, and Cheng-Ming Chuonga,h,i,1 aDepartment of Pathology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90033; bDepartment of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Hunan 410008, China; cLouisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge, Grand Chenier, LA 70643; dEnvironmental Health Science and eDepartment of Small Animal Medicine and Surgery, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602; fDepartment of Dentistry and iResearch Center for Wound Repair and Regeneration, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan City 70101, Taiwan; and gSchool of Dentistry and hResearch Center for Developmental Biology and Regenerative Medicine, National Taiwan University, Taipei 10617, Taiwan Edited by Edward M. De Robertis, Howard Hughes Medical Institute/University of California, Los Angeles, CA, and accepted by the Editorial Board March 28, 2013 (received for review July 31, 2012) Reptiles and fish have robust regenerative powers for tooth renewal. replaced from the dental lamina connected to the lingual side of However, extant mammals can either renew their teeth one time the deciduous tooth (15). Human teeth are only replaced one time; (diphyodont dentition) or not at all (monophyodont dentition). however, a remnant of the dental lamina still exists (16) and may Humans replace their milk teeth with permanent teeth and then become activated later in life to form odontogenic tumors (17). lose their ability for tooth renewal. -

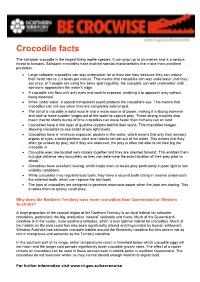

Crocodile Facts and Figures

Crocodile facts The saltwater crocodile is the largest living reptile species. It can grow up to six metres and is a serious threat to humans. Saltwater crocodiles have evolved special characteristics that make them excellent predators. • Large saltwater crocodiles can stay underwater for at least one hour because they can reduce their heart rate to 2-3 beats per minute. This means that crocodiles can wait underwater until they see prey, or if people are using the same spot regularly, the crocodile can wait underwater until someone approaches the water’s edge. • A crocodile can float with only eyes and nostrils exposed, enabling it to approach prey without being detected. • When under water, a special transparent eyelid protects the crocodile’s eye. This means that crocodiles can still see when they are completely submerged. • The tail of a crocodile is solid muscle and a major source of power, making it a strong swimmer and able to make sudden lunges out of the water to capture prey. These strong muscles also mean that for shorts bursts of time crocodiles can move faster than humans can on land. • Crocodiles have a thin layer of guanine crystals behind their retina. This intensifies images, allowing crocodiles to see better at low light levels. • Crocodiles have a ‘minimum exposure’ posture in the water, which means that only their sensory organs of eyes, cranial platform, ears and nostrils remain out of the water. This means that they often go unseen by prey, but if they are observed, the prey is often not able to tell how big the crocodile is. -

Longitudinal Studies on Tooth Replacement in the Leopard

LONGITUDINAL STUDIES ON TOOTH REPLACEMENT IN THE LEOPARD GECKO by Andrew Carlton Edward Wong BMSc, DDS, The University of Alberta, 2011 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Craniofacial Science) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) July 2015 © Andrew Carlton Edward Wong, 2015 Abstract The leopard gecko is an emerging reptilian model for the molecular basis of indefinite tooth replacement. Here we characterize the tooth replacement frequency and pattern of tooth loss in the normal adult gecko. We chose to perturb the system of tooth replacement by activating the Wingless signaling pathway (Wnt). Misregulation of Wnt leads to supernumerary teeth in mice and humans. We hypothesized by activating Wnt signaling with LiCl, tooth replacement frequency would increase. To measure the rate of tooth loss and replacement, weekly dental wax bites of 3 leopard geckos were taken over a 35-week period. The present/absent tooth positions were recorded. During the experimental period, the palate was injected bilaterally with NaCl (control) and then with LiCl. The geckos were to be biological replicates. Symmetry was analyzed with parametric tests (repeated measures ANOVA, Tukey’s post-hoc), while time for emergence and total absent teeth per week were analyzed with non- parametric tests (Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA, Mann-Whitney U post-hoc and Bonferroni Correction). The average replacement frequency was 6-7 weeks and posterior-to-anterior waves of replacement were formed. Right to left symmetry between individual tooth positions was high (>80%) when all teeth were included but dropped to 50% when only absent teeth were included. -

Veterinary Dentistry Basics

Veterinary Dentistry Basics Introduction This program will guide you, step by step, through the most important features of veterinary dentistry in current best practice. This chapter covers the basics of veterinary dentistry and should enable you to: ü Describe the anatomical components of a tooth and relate it to location and function ü Know the main landmarks important in assessment of dental disease ü Understand tooth numbering and formulae in different species. ã 2002 eMedia Unit RVC 1 of 10 Dental Anatomy Crown The crown is normally covered by enamel and meets the root at an important landmark called the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ). The CEJ is anatomically the neck of the tooth and is not normally visible. Root Teeth may have one or more roots. In those teeth with two or more roots the point where they diverge is called the furcation angle. This can be a bifurcation or a trifurcation. At the end of the root is the apex, which can have a single foramen (humans), a multiple canal delta arrangement (cats and dogs) or remain open as in herbivores. In some herbivores the apex closes eventually (horse) whereas whereas in others it remains open throughout life. The apical area is where nerves, blood vessels and lymphatics travel into the pulp. Alveolar Bone The roots are encased in the alveolar processes of the jaws. The process comprises alveolar bone, trabecular bone and compact bone. The densest bone lines the alveolus and is called the cribriform plate. It may be seen radiographically as a white line called the lamina dura. -

Identification Notes &~@~-/~: ~~*~@~,~ 'PTILE

CATEGORY Identification Notes &~@~-/~: ~~*~@~,~ ‘PTILE for wildlife law enforcement ~ C.rnrn.n N.rn./s: Al@~O~, c~~~dil., ~i~.xl, Gharial PROBLEM: Skulls of Crocodilians are often imported as souvenirs. nalch (-”W 4(JI -“by ieeth ??la&ularJy+i9 GUIDE TO PRELIMINARY IDENTIFICATION OF CROCODILL4N SKULLS 1. Nasal bones separated from nasal aperture; mandibular symphysis extends to the 15th tooth. 2. Gavialis gangeticus Nasal bones entering the nasal aperture; mandibular symphysisdoes not extend beyond the8th tooth . Tomistoma schlegelii 2. Nasal bones separated from premaxillary bones; 27 -29maxi11aryteeth,25 -26mandibularteeth Nasal bones in contact with premaxillaq bo Qoco@khs acutus teeth, 18-19 mandibular teeth . Tomiitomaschlegelii 3. Fourth mandibular tooth usually fitting into a notch in the maxilla~, 16-19 maxillary teeth, 14-15 mandibular teeth . .4 Osteolaemus temaspis Fourth mandibular tooth usually fitting into a pit in the maxilla~, 14-20 maxillary teeth, 17-22 mandibular teeth . .5 4. Nasal bones do not divide nasal aperture. .. CrocodylW (12 species) Alligator m&siss@piensh Nasalboncx divide nasal aperture . Osteolaemustetraspk. 5. Nasal bones do not divide nasal aperture. .6 . Paleosuchus mgonatus Bony septum divides nasal aperture . .. Alligator (2 species) 6. Fiveteethinpremaxilla~ bone . .7 . Melanosuchus niger Four teeth in premaxillary bone. ...Paleosuchus (2species) 7. Vomerexposed on the palate . Melanosuchusniger Caiman crocodiles Vomer not exposed on palate . ...”..Caiman (2species) Illustrations from: Moo~ C. C 1921 Me&m, F. 19S1 L-.. Submitted by: Stephen D. Busack, Chief, Morphology Section, National Fish& Wildlife Forensics LabDate submitted 6/3/91 Prepared in cooperation with the National Fkh & Wdlife Forensics Laboratoy, Ashlar@ OR, USA ‘—m More on reverse side>>> IDentMcation Notes CATEGORY: REPTILE for wildlife law enforcement -- Crocodylia II CAmmom Nda Alligator, Crocodile, Caiman, Gharial REFERENCES Medem, F. -

SHARK FACTS There Are 510 Species of Sharks

1 SHARK FACTS There are 510 species of sharks. Let’s learn more about a few of them. Common Six-gilled Thresher Shark Shark • Known for its 10 foot tail • Can grow up to 16 feet long • Stuns and herds fish with its long tail • Has six pairs of gills instead of the average of five • Warm blooded • Has one dorsal fin at the back of its body • Feeds on squid and schooling fish • Also known as cow shark or mud shark • Prefers to stay towards the top of deep bodies • Deep water shark of water Shortfin Great Mako Hammerhead Shark Shark • Bluish gray on top part of body and white on • Eyes are at opposite sides of its rectangular the belly shaped head • Has extremely sharp teeth, that stick out even when • Feeds on crustaceans, octopuses, rays and its mouth is shut small sharks • Feeds on sharks, swordfish and tuna • Usually found around tropical reefs • Jumps high in the air to escape fishing hooks • Can give birth to over 40 pups in one litter • Fastest of all the sharks as it can swim over 30 mph • Has a heigtened sense of electro-reception 2 SHARK FACTS Bull Nurse Shark Shark • Can grow up to 11 feet long and over 200 pounds • Has long, fleshy appendages called barbels that hang below its snout • Gray to brown in color with a white belly • Feeds on crab, lobster, urchins and fish • Feeds on fish, dolphins, sea turtles and other sharks • Usually found near rocky reefs, mudflats • Found in fresh and salt water and sandbars • Aggressive species • Enjoys laying on the ocean floor • Nocturnal animal Great Epaulette White Shark Shark • Can grow -

From Molecules to Mastication: the Development and Evolution of Teeth Andrew H

Advanced Review From molecules to mastication: the development and evolution of teeth Andrew H. Jheon,1,† Kerstin Seidel,1,† Brian Biehs1 and Ophir D. Klein1,2∗ Teeth are unique to vertebrates and have played a central role in their evolution. The molecular pathways and morphogenetic processes involved in tooth development have been the focus of intense investigation over the past few decades, and the tooth is an important model system for many areas of research. Developmental biologists have exploited the clear distinction between the epithelium and the underlying mesenchyme during tooth development to elucidate reciprocal epithelial/mesenchymal interactions during organogenesis. The preservation of teeth in the fossil record makes these organs invaluable for the work of paleontologists, anthropologists, and evolutionary biologists. In addition, with the recent identification and characterization of dental stem cells, teeth have become of interest to the field of regenerative medicine. Here, we review the major research areas and studies in the development and evolution of teeth, including morphogenesis, genetics and signaling, evolution of tooth development, and dental stem cells. © 2012 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. How to cite this article: WIREs Dev Biol 2013, 2:165–182. doi: 10.1002/wdev.63 MORPHOGENESIS AND of natural selection in response to the environmental DEVELOPMENT pressures provided by various types of food (Figure 2). Teeth, or tooth-like structures called odontodes he formation of a head with complex jaws or denticles, are present in all vertebrate groups, Tand networked sensory organs was a central although they have been lost in some lineages. Most innovation in the evolution of vertebrates, allowing fish and reptiles, and many amphibians, possess 1 the shift to an active predatory lifestyle. -

PA Marketplace Glossary of Dental Terms

Glossary of Dental Terms DENTAQUEST Pennsylvania INSURANCE TERMS ACA: The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (Pub. L. 111-148). For example, if the health insurance or plan’s allowed amount for an office visit is $100 and Adverse determination: means a decision by the Plan you’ve met your deductible, your co- or a representative of the Plan to deny, reduce, or insurance payment of 20% would be $20. modify the availability of any dental care services, The health insurance or plan pays the rest of because your condition failed to meet the require- the allowed amount. ments for coverage based on necessity, appropriate- ness of care, level of care, or effectiveness. Co-payment: A fixed amount (for example, $15) you pay for a covered health care Agreement: refers to the Account Dental Service service, usually when you receive the service. Agreement, a contract between the Plan and the Plan The amount can vary by the type of covered Sponsor that provides benefits for dental services. health care service. The Account Dental Service Agreement includes the Subscriber’s Certificate, Schedule of Benefits, Coverage decision: an initial determination by Group Application, Enrollment Form, rates identified in the Plan, or a representative of the Plan that Attachment A, and any applicable Riders, Endorse- results in noncoverage of a health care ments and Supplemental Agreements. service. Coverage decision includes nonpayment of all or any part of a claim, but Appeal: a protest filed by a Covered Individual or a does not include an adverse determination as health care provider with the Plan under its internal defined above. -

Autocrine and Paracrine Shh Signaling Are Necessary for Tooth Morphogenesis, but Not Tooth Replacement in Snakes and Lizards (Squamata)

Developmental Biology 337 (2010) 171–186 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Developmental Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/developmentalbiology Evolution of Developmental Control Mechanisms Autocrine and paracrine Shh signaling are necessary for tooth morphogenesis, but not tooth replacement in snakes and lizards (Squamata) Gregory R. Handrigan, Joy M. Richman ⁎ Department of Oral Health Sciences, Faculty of Dentistry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada article info abstract Article history: Here we study the role of Shh signaling in tooth morphogenesis and successional tooth initiation in snakes Received for publication 30 August 2009 and lizards (Squamata). By characterizing the expression of Shh pathway receptor Ptc1 in the developing Revised 12 October 2009 dentitions of three species (Eublepharis macularius, Python regius, and Pogona vitticeps) and by performing Accepted 12 October 2009 gain- and loss-of-function experiments, we demonstrate that Shh signaling is active in the squamate tooth Available online 20 October 2009 bud and is required for its normal morphogenesis. Shh apparently mediates tooth morphogenesis by separate paracrine- and autocrine-mediated functions. According to this model, paracrine Shh signaling Keywords: Reptile induces cell proliferation in the cervical loop, outer enamel epithelium, and dental papilla. Autocrine Evolution signaling within the stellate reticulum instead appears to regulate cell survival. By treating squamate dental Development explants with Hh antagonist cyclopamine, we induced tooth phenotypes that closely resemble the Odontogenesis morphological and differentiation defects of vestigial, first-generation teeth in the bearded dragon P. Sonic hedgehog vitticeps. Our finding that these vestigial teeth are deficient in epithelial Shh signaling further corroborates Patched1 that Shh is needed for the normal development of teeth in snakes and lizards. -

Proces Wymiany Zębów U Wybranych Grup Ssaków W Ujęciu Ewolucyjnym

Tom 70 2021 Numer 1 (330) Strony 83–93 Paweł Muniak Wydział Biologii Uniwersytet Jagielloński Gronostajowa 7, 30-387 Kraków E-mail: [email protected] PROCES WYMIANY ZĘBÓW U WYBRANYCH GRUP SSAKÓW W UJĘCIU EWOLUCYJNYM WSTĘP pod względem wymiany zębowej wyjątkowe, gdyż tylko u nich widać kształtującą się w Wymiana zębów u zwierząt kręgowych ciągu ewolucji tendencję do difiodoncji, czy- jest ważnym zjawiskiem zarówno w ska- li wytwarzania jedynie dwóch pokoleń zę- li osobnika, zwiększającym jego dostosowa- bów: mlecznych i stałych, wymienianych w nie do środowiska i co za tym idzie, szan- skoordynowany sposób w ciągu krótkiego se przeżycia, jak i w szerszej perspektywie czasu życia zwierzęcia (zazwyczaj pomiędzy ewolucyjnej, pokazując trendy ewolucyjne w ukończeniem stadium oseska a dojrzałością obrębie całych grup. płciową) (SZARSKI 1998). Wymiana uzębienia jest powszechna wśród zwierząt. Większość zwierząt posiada- TERMINOLOGIA jących zęby wymienia je na nowe, stosując różne strategie. Najczęstszym typem wymia- W niniejszej pracy będę posługiwał się ny jest polifiodoncja. Polega ona na tym, że ogólnie przyjętymi skrótami z terminolo- utracony ząb jest zastępowany przez nowy, gii anatomicznej, gdzie zęby szczęki (górne) wyrastający na jego miejscu. W taki sposób będą oznaczane wielką literą: I, C, P, M, a wymienia zęby większość gadów, u których zęby żuchwy (dolne) małą literą: i, c, p, m. wymieniane są one w sposób przypadko- I tak: wy: gdy jeden ulegnie złamaniu lub wypad- nie, na jego miejsce wyrasta nowy. U ryb I/i – siekacz, chrzęstnoszkieletowych, w tym rekinów, zna- C/c – kieł, ne są inne mechanizmy wymiany uzębienia, P/p – ząb przedtrzonowy, tzn. spirale zębowe, pozwalające na wymianę M/m – ząb trzonowy. -

Tooth Anatomy

Tooth Anatomy To understand some of the concepts and terms that we use in discussing dental conditions, it is helpful to have a picture of what these terms represent. This picture is from the American Veterinary Dental College. Pulp Dentin Crown Enamel Gingiva Root Periodontal Ligament Alveolar Bone supporting the tooth Crown: The portion of the tooth projecting from the gums. It is covered by a layer of enamel, though dentin makes up the bulk of the tooth structure. The crown is the working part of the tooth. In dogs and cats, most teeth are conical or pyramidal in shape for cutting and shearing action. Gingiva: The gum tissue surrounds the crown of the tooth and protects the root and bone which are subgingival (below the gum line). The gingiva is the first line of defense against periodontal disease. The space where the gingiva meets the crown is where periodontal pockets develop. Measurements are taken here with a periodontal probe to assess the stage of periodontal disease. When periodontal disease progresses it can involve the Alveolar Bone, leading to bone loss and root exposure. Root Canal: The root canal contains the pulp. This living tissue is protected by the crown and contains blood vessels, nerves and specialized cells that produce dentin. Dentin is produced throughout the life of the tooth, which causes the pulp canal to narrow as pets age. Damage to the pulp causes endodontic disease which is painful, and can lead to infection and loss of the tooth. Periodontal Ligament: This tissue is what connects the tooth root to the bone to keep it anchored to its socket.