Fragmentation and Connectivity of Island Forests In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ED45E Rare and Scarce Species Hierarchy.Pdf

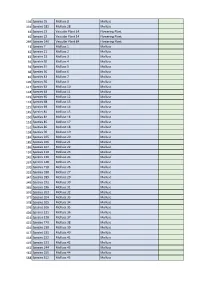

104 Species 55 Mollusc 8 Mollusc 334 Species 181 Mollusc 28 Mollusc 44 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 45 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 269 Species 149 Vascular Plant 84 Flowering Plant 13 Species 7 Mollusc 1 Mollusc 42 Species 21 Mollusc 2 Mollusc 43 Species 22 Mollusc 3 Mollusc 59 Species 30 Mollusc 4 Mollusc 59 Species 31 Mollusc 5 Mollusc 68 Species 36 Mollusc 6 Mollusc 81 Species 43 Mollusc 7 Mollusc 105 Species 56 Mollusc 9 Mollusc 117 Species 63 Mollusc 10 Mollusc 118 Species 64 Mollusc 11 Mollusc 119 Species 65 Mollusc 12 Mollusc 124 Species 68 Mollusc 13 Mollusc 125 Species 69 Mollusc 14 Mollusc 145 Species 81 Mollusc 15 Mollusc 150 Species 84 Mollusc 16 Mollusc 151 Species 85 Mollusc 17 Mollusc 152 Species 86 Mollusc 18 Mollusc 158 Species 90 Mollusc 19 Mollusc 184 Species 105 Mollusc 20 Mollusc 185 Species 106 Mollusc 21 Mollusc 186 Species 107 Mollusc 22 Mollusc 191 Species 110 Mollusc 23 Mollusc 245 Species 136 Mollusc 24 Mollusc 267 Species 148 Mollusc 25 Mollusc 270 Species 150 Mollusc 26 Mollusc 333 Species 180 Mollusc 27 Mollusc 347 Species 189 Mollusc 29 Mollusc 349 Species 191 Mollusc 30 Mollusc 365 Species 196 Mollusc 31 Mollusc 376 Species 203 Mollusc 32 Mollusc 377 Species 204 Mollusc 33 Mollusc 378 Species 205 Mollusc 34 Mollusc 379 Species 206 Mollusc 35 Mollusc 404 Species 221 Mollusc 36 Mollusc 414 Species 228 Mollusc 37 Mollusc 415 Species 229 Mollusc 38 Mollusc 416 Species 230 Mollusc 39 Mollusc 417 Species 231 Mollusc 40 Mollusc 418 Species 232 Mollusc 41 Mollusc 419 Species 233 -

Lamiales Newsletter

LAMIALES NEWSLETTER LAMIALES Issue number 4 February 1996 ISSN 1358-2305 EDITORIAL CONTENTS R.M. Harley & A. Paton Editorial 1 Herbarium, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3AE, UK The Lavender Bag 1 Welcome to the fourth Lamiales Universitaria, Coyoacan 04510, Newsletter. As usual, we still Mexico D.F. Mexico. Tel: Lamiaceae research in require articles for inclusion in the +5256224448. Fax: +525616 22 17. Hungary 1 next edition. If you would like to e-mail: [email protected] receive this or future Newsletters and T.P. Ramamoorthy, 412 Heart- Alien Salvia in Ethiopia 3 and are not already on our mailing wood Dr., Austin, TX 78745, USA. list, or wish to contribute an article, They are anxious to hear from any- Pollination ecology of please do not hesitate to contact us. one willing to help organise the con- Labiatae in Mediterranean 4 The editors’ e-mail addresses are: ference or who have ideas for sym- [email protected] or posium content. Studies on the genus Thymus 6 [email protected]. As reported in the last Newsletter the This edition of the Newsletter and Relationships of Subfamily Instituto de Quimica (UNAM, Mexi- the third edition (October 1994) will Pogostemonoideae 8 co City) have agreed to sponsor the shortly be available on the world Controversies over the next Lamiales conference. Due to wide web (http://www.rbgkew.org. Satureja complex 10 the current economic conditions in uk/science/lamiales). Mexico and to allow potential partici- This also gives a summary of what Obituary - Silvia Botta pants to plan ahead, it has been the Lamiales are and some of their de Miconi 11 decided to delay the conference until uses, details of Lamiales research at November 1998. -

The Insect Fauna Associated with Horehound (Marrubium Vulgare L

Plant Protection Quarterly Vol.15(1) 2000 21 belonging to eight orders were found feeding on the plant (Figure 2, Table 2). The insect fauna associated with horehound The insects included 12 polyphagous spe- (Marrubium vulgare L.) in western Mediterranean cies (44%), 8 oligophagous species (30%) and 7 monophagous species (26%). At the Europe and Morocco: potential for biological control larval stage, there were five root-feeding in Australia species (22%), one stem-boring species (4%), nine leaf-feeding species (39%), eight flower, ovary or seed feeding species A Jean-Louis Sagliocco , Keith Turnbull Research Institute, Victorian (34%). Based on adult feeding behaviour Department of Natural Resources and Environment, CRC for Weed there was one root-boring species (74%), Management Systems, PO Box 48, Frankston, Victoria 3199, Australia. six leaf-feeding species (40%) and eight A Previous address: CSIRO European Laboratory, Campus International de species feeding on flowers or ovaries or Baillarguet, 34980 Montferrier sur Lez, Cedex, France. seeds (53%). Wheeleria spilodactylus (Curtis) Summary were preserved. Immature stages were (Lepidoptera: Pterophoridae) Marrubium vulgare L. (Lamiaceae) was kept with fresh plant material until the Wheeleria spilodactylus was abundant at surveyed in western Mediterranean Eu- adult stage for identification. Insects most sites in France and Spain, and had rope and Morocco to identify the phy- were observed either in the field or the been recorded feeding on M. vulgare tophagous insect fauna associated with laboratory to confirm that they fed on the (Gielis 1996) and Ballota nigra (Bigot and this weed and to select species having plant. Insects were sent to museum spe- Picard 1983). -

Ballota Nigral. – an Overview of Pharmacological Effects And

International journal edited by the Institute of Natural Fibres and Medicinal Plants Vol. 66 No. 3 2020 Received: 2020-09-02 DOI: 10.2478/hepo-2020-0014 Accepted: 2020-09-22 Available online: 2020-09-30 EXPERIMENTALREVIEW PAPER PAPER Ballota nigra L. – an overview of pharmacological effects and traditional uses FILIP PRZERWA1 , ARNOLD KUKOWKA1 , IZABELA UZAR2* 1Student Science Club Department of General Pharmacology and Pharmacoeconomics Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin Żołnierska 48 71-210 Szczecin, Poland 2Department of General Pharmacology and Pharmacoeconomics Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin Żołnierska 48 71-210 Szczecin, Poland * corresponding author: e-mail: [email protected] Summary Ballota nigra, also known as black horehound is a common medical herb used in folk medicine around the world. First reported mentions of its medical properties and use goes as far as the 13th century. The use of black horehound depends on regions and countries. It is used mostly to treat e.g. mild sleep disorders, nervousness, upset stomach, wound healing. It can be used as an anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antipro- tozoal, antifungal drug. Moreover, it has been reported as a potential cancer drug. This extensive usage is particularly interesting for us. The aim of this review is to present available data on B. nigra pharmacological effects and known traditional uses gathered from a wide range of scientific articles published in 1997–2020. Key words: Ballota nigra L., black horehound, pharmacology, medical herb Słowa kluczowe: Ballota nigra L., mierznica czarna, farmakologia, roślina lecznicza Herba Pol 2020; 66(3): 56-65 Ballota nigra L. – an overview of pharmacological effects and traditional uses 57 INTRODUCTION responsible for a given effect. -

2017 City of York Biodiversity Action Plan

CITY OF YORK Local Biodiversity Action Plan 2017 City of York Local Biodiversity Action Plan - Executive Summary What is biodiversity and why is it important? Biodiversity is the variety of all species of plant and animal life on earth, and the places in which they live. Biodiversity has its own intrinsic value but is also provides us with a wide range of essential goods and services such as such as food, fresh water and clean air, natural flood and climate regulation and pollination of crops, but also less obvious services such as benefits to our health and wellbeing and providing a sense of place. We are experiencing global declines in biodiversity, and the goods and services which it provides are consistently undervalued. Efforts to protect and enhance biodiversity need to be significantly increased. The Biodiversity of the City of York The City of York area is a special place not only for its history, buildings and archaeology but also for its wildlife. York Minister is an 800 year old jewel in the historical crown of the city, but we also have our natural gems as well. York supports species and habitats which are of national, regional and local conservation importance including the endangered Tansy Beetle which until 2014 was known only to occur along stretches of the River Ouse around York and Selby; ancient flood meadows of which c.9-10% of the national resource occurs in York; populations of Otters and Water Voles on the River Ouse, River Foss and their tributaries; the country’s most northerly example of extensive lowland heath at Strensall Common; and internationally important populations of wetland birds in the Lower Derwent Valley. -

NVEO 2017, Volume 4, Issue 4, Pages 14-27

Nat. Volatiles & Essent. Oils, 2017: 4(4): 14-27 Celep & Dirmenci REVIEW Systematic and Biogeographic overview of Lamiaceae in Turkey Ferhat Celep1,* and Tuncay Dirmenci2 1 Mehmet Akif Ersoy mah. 269. cad. Urankent Prestij Konutları, C16 Blok, No: 53, Demetevler, Ankara, TURKEY 2 Biology Education, Necatibey Education Faculty, Balıkesir University, Balıkesir, TURKEY *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Lamiaceae is the third largest family based on the taxon number and fourth largest family based on the species number in Turkey. The family has 48 genera and 782 taxa (603 species, 179 subspecies and varieties), 346 taxa (271 species, 75 subspecies and varieties) of which are endemic (ca. 44%) (data updated 1th February 2017) in the country. There are also 23 hybrid species, 19 of which are endemic (82%). The results proven that Turkey is one of the centers of diversity for Lamiaceae in the Old World. In addition, Turkey has about 10% of all Lamiaceae members in the World. The largest five genera in the country based on the taxon number are Stachys (118 taxa), Salvia (107 taxa), Sideritis (54 taxa), Phlomis (53 taxa) and Teucrium (49 taxa). According to taxon number, five genera with the highest endemism ratio are Dorystaechas (1 taxon, 100%), Lophantus (1 taxon, 100%), Sideritis (54 taxa, 74%), Drymosiphon (9 taxa, 67%), and Marrubium (27 taxa, 63%). There are two monotypic genera in Turkey as Dorystaechas and Pentapleura. Turkey sits on the junction of three phytogeographic regions with highly diverse climate and the other ecologic features. Phytogeographic distribution of Turkish Lamiaceae taxa are 293 taxa in the Mediterranean (37.4%), 267 taxa in the Irano-Turanian (36.7%), 90 taxa in the Euro-Siberian (Circumboreal) phytogeographic region, and 112 taxa in Unknown or Multiregional (14.3%) phytogeographical elements. -

Antioxidant Activity of Tissue Culture-Raised Ballota Nigra L

Acta Poloniae Pharmaceutica ñ Drug Research, Vol. 72 No. 4 pp. 769ñ775, 2015 ISSN 0001-6837 Polish Pharmaceutical Society ANTIOXIDANT ACTIVITY OF TISSUE CULTURE-RAISED BALLOTA NIGRA L. PLANTS GROWN EX VITRO JOANNA MAKOWCZY—SKA*, IZABELA GRZEGORCZYK-KAROLAK and HALINA WYSOKI—SKA Department of Biology and Pharmaceutical Botany, Medical University of £Ûdü, 1 MuszyÒskiego St., 90-151 £Ûdü, Poland Abstract: Antioxidant properties and total phenolic and flavonoid contents were evaluated in methanolic extracts of shoots from Ballota nigra plants initiated in vitro (from nodal explants) and in vivo (from seeds). The plants were grown in greenhouse and in the field, and were analyzed at the vegetative and flowering stages. The shoot extract of wild-grown plants of B. nigra was also investigated. The results indicate that antioxidant poten- tial of the B. nigra extracts seems to be due to their scavenging of free radicals (DPPH assay) and metal reduc- ing (FRAP test), while they were less effective at the prevention of linoleic acid peroxidation (LPO test). The extracts from shoots of in vitro derived plants were found to exhibit the greatest antioxidant properties. The extracts were also characterized by the highest content of phenolic compounds and their level was affected by plant developmental stage. The extracts of shoots collected at the flowering period exhibited higher amounts of phenolics and flavonoids than in the extracts of immature plants. A close correlation between the total pheno- lic content and flavonoid content and antioxidant activity using the DPPH and FRAP assays was obtained. The results of the present study suggest the use in vitro-derived plants of B. -

CBD First National Report

FIRST NATIONAL REPORT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA TO THE UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION ON BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY July 2010 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................... 3 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 4 2. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Geographic Profile .......................................................................................... 5 2.2 Climate Profile ...................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Population Profile ................................................................................................. 7 2.4 Economic Profile .................................................................................................. 7 3 THE BIODIVERSITY OF SERBIA .............................................................................. 8 3.1 Overview......................................................................................................... 8 3.2 Ecosystem and Habitat Diversity .................................................................... 8 3.3 Species Diversity ............................................................................................ 9 3.4 Genetic Diversity ............................................................................................. 9 3.5 Protected Areas .............................................................................................10 -

Spathulenol As the Most Abundant Component of Essential Oil of Moluccella Aucheri (Boiss.) Scheen

Nat. Volatiles & Essent. Oils, 2021; 8(2): 37-41 Doorandishan et al. DOI: 10.37929/nveo.817562 RESEARCH ARTICLE Spathulenol as the most abundant component of essential oil of Moluccella aucheri (Boiss.) Scheen Mina Doorandishan1,2, Morteza Gholami1, Pouneh Ebrahimi1 and Amir Reza Jassbi2, * 1Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Sciences, Golestan University, Gorgan, IRAN 2Medicinal and Natural Products Chemistry Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, IRAN *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Submitted: 01.11.2020; Accepted: 17.03.2021 Abstract The genus Moluccella (Lamiaceae) encompasses eight species among which Moluccella aucheri (Boiss.) Scheen and M. laevis L. are available in Iran. The aim of this study is characterizing the essential oil of dried aerial parts of M. aucheri collected from the South of Iran. The essential oil was hydrodistilled and then analysed by GC-MS. Twenty-one compounds were identified in the oil of M. aucheri. The most abundant components of the oil were an aromadendrane sesquiterpene; spathulenol (63.3%) together with a diterpenoid; phytol (3.5%) and a linear sesquiterpene, E-nerolidol (3.1%). Keywords: Essential oil, Moluccella aucheri, spathulenol, Lamiaceae Introduction Moluccella aucheri (Boiss.) Scheen (syn. Otostegia aucheri Boiss.) belongs to Moluccella genus and is native to Iran and Pakistan (Scheen & Albert, 2007, 2009). This genus encompasses eight species which are widely distributed in South-Western Asia and the Mediterranean (http://wcsp.science.kew.org/). There are only two species of Moluccella genus reported from Iran; M. aucheri and M. laevis L. of which the earlier is growing wild in the South of the country (Mozaffarian, 2013). -

Pharmacological Activities of Ballota Acetabulosa (L.) Benth: a Mini Review

Pharmacy & Pharmacology International Journal Mini Review Open Access Pharmacological activities of Ballota acetabulosa (L.) Benth: A mini review Abstract Volume 8 Issue 3 - 2020 The Ballota L. genera belonging to the Lamiaceae family found mainly in the Mediterranean Sanjay Kumar,1 Reshma Kumari2 area, Middle East, and North Africa. From the ancient times this genus has been largely 1Department of Botany, Govt. P.G. College, India explored for their biological properties. Phytochemical investigations of Ballota species 2Department of Botany and Microbiology, Gurukula Kangri have revealed that diterpenoids are the main constituents of the genera. A large number Vishwavidhyalaya, India of flavonoids and other metabolites were also identified. This mini review covers the traditional and pharmacological properties of Ballota acetabulosa (L.) Benth species. Correspondence: Reshma Kumari, Department of Botany and Microbiology, Gurukula Kangri Vishwavidhyalaya, Haridwar-249404, India, Tel +918755388132, Email Received: May 15, 2020 | Published: June 22, 2020 Introduction Pharmacological activity All over the world various plants have been used as medicine. Dugler and Dugler investigated the antimicrobial activities of More recently, plant extracts have been developed and proposed for methanolic leaf extracts of B. acetabulosa by disc diffusion and various biological process. In developing countries herbal medicine microdilution method against Enterococcus faecalis, Escherichia has been improved as a substitute solution to health problems coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus and costs of pharmaceutical products. The development of drug mirabilis and Candida albicans pathogens causing complicated resistance pathogens against antibiotics has required a search for new urine tract infections. They observed strong antimicrobial activity antimicrobial substances from other sources, including plants. -

Lamiales – Synoptical Classification Vers

Lamiales – Synoptical classification vers. 2.6.2 (in prog.) Updated: 12 April, 2016 A Synoptical Classification of the Lamiales Version 2.6.2 (This is a working document) Compiled by Richard Olmstead With the help of: D. Albach, P. Beardsley, D. Bedigian, B. Bremer, P. Cantino, J. Chau, J. L. Clark, B. Drew, P. Garnock- Jones, S. Grose (Heydler), R. Harley, H.-D. Ihlenfeldt, B. Li, L. Lohmann, S. Mathews, L. McDade, K. Müller, E. Norman, N. O’Leary, B. Oxelman, J. Reveal, R. Scotland, J. Smith, D. Tank, E. Tripp, S. Wagstaff, E. Wallander, A. Weber, A. Wolfe, A. Wortley, N. Young, M. Zjhra, and many others [estimated 25 families, 1041 genera, and ca. 21,878 species in Lamiales] The goal of this project is to produce a working infraordinal classification of the Lamiales to genus with information on distribution and species richness. All recognized taxa will be clades; adherence to Linnaean ranks is optional. Synonymy is very incomplete (comprehensive synonymy is not a goal of the project, but could be incorporated). Although I anticipate producing a publishable version of this classification at a future date, my near- term goal is to produce a web-accessible version, which will be available to the public and which will be updated regularly through input from systematists familiar with taxa within the Lamiales. For further information on the project and to provide information for future versions, please contact R. Olmstead via email at [email protected], or by regular mail at: Department of Biology, Box 355325, University of Washington, Seattle WA 98195, USA. -

A Synoptical Classification of the Lamiales

Lamiales – Synoptical classification vers. 2.0 (in prog.) Updated: 13 December, 2005 A Synoptical Classification of the Lamiales Version 2.0 (in progress) Compiled by Richard Olmstead With the help of: D. Albach, B. Bremer, P. Cantino, C. dePamphilis, P. Garnock-Jones, R. Harley, L. McDade, E. Norman, B. Oxelman, J. Reveal, R. Scotland, J. Smith, E. Wallander, A. Weber, A. Wolfe, N. Young, M. Zjhra, and others [estimated # species in Lamiales = 22,000] The goal of this project is to produce a working infraordinal classification of the Lamiales to genus with information on distribution and species richness. All recognized taxa will be clades; adherence to Linnaean ranks is optional. Synonymy is very incomplete (comprehensive synonymy is not a goal of the project, but could be incorporated). Although I anticipate producing a publishable version of this classification at a future date, my near-term goal is to produce a web-accessible version, which will be available to the public and which will be updated regularly through input from systematists familiar with taxa within the Lamiales. For further information on the project and to provide information for future versions, please contact R. Olmstead via email at [email protected], or by regular mail at: Department of Biology, Box 355325, University of Washington, Seattle WA 98195, USA. Lamiales – Synoptical classification vers. 2.0 (in prog.) Updated: 13 December, 2005 Acanthaceae (~201/3510) Durande, Notions Elém. Bot.: 265. 1782, nom. cons. – Synopsis compiled by R. Scotland & K. Vollesen (Kew Bull. 55: 513-589. 2000); probably should include Avicenniaceae. Nelsonioideae (7/ ) Lindl. ex Pfeiff., Nomencl.