Times of War and War Over Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fellowship Primer

The Fellowship Primer Excerpts from the Paul Solomon Source Work-Readings for the Fellowship of the Inner Light Compiled and Edited by Grace de Rond Editor’s Note The purpose of The Fellowship Primer is to share the message of the Paul Solomon Source and to help individuals better understand the story, the nature and the purposes of the Fellowship of the Inner Light. I first heard of Paul Solomon in 1974 through the initial book on Paul’s work as a spiritual teacher and a psychic channel: Excerpts from the Paul Solomon Tapes compiled by Daniel Emmanuel and Tom Johnson. Within a year of reading the book, I made my way to Virginia Beach, VA and showed up at the door of Paul’s organization to volunteer. This was 1975, and I was assigned the task of indexing Paul’s trance readings low-tech style, using a cassette tape player, enormous old-fashioned headphones on a spiral cord, and a notepad and pencil. From the first audible word, I fell in love. More than three decades later, much of who I am is a result of my study of Paul’s work and my experience of him as a personal teacher. In 1977, I received a personal reading from Paul that described my role with his work. “Let your direction be in cataloging, indexing and making of value the information that is set before you. Through the categorizing, become an authority on what is given and said. Spare no moment in sharing it. Be of assistance in every way, in allowing the facts, ideas and concepts that are here to become more and better known. -

Mark at the Threshold

Mark at the Threshold WEBB_f1_i-xii.indd i 3/26/2008 6:57:46 PM Biblical Interpretation Series Editors R. Alan Culpepper Ellen van Wolde Associate Editors David E. Orton Rolf Rendtorff Editorial Advisory Board Janice Capel Anderson – Phyllis A. Bird Erhard Blum – Werner H. Kelber Ekkehard W. Stegemann – Vincent L. Wimbush Jean Zumstein VOLUME 95 WEBB_f1_i-xii.indd ii 3/26/2008 6:57:50 PM Mark at the Threshold Applying Bakhtinian Categories to Markan Characterisation By Geoff R. Webb LEIDEN • BOSTON 2008 WEBB_f1_i-xii.indd iii 3/26/2008 6:57:50 PM This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Webb, Geoff R. Mark at the threshold : applying Bakhtinian categories to Markan characterisation / by Geoff R. Webb. p. cm. — (Biblical interpretation series ; v. 95) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-16774-2 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Bible. N.T. Mark—Criticism, interpretation, etc. 2. Bakhtin, M.M. (Mikhail Mikhailovich), 1895–1975. I. Title. II. Series. BS2585.52.W43 2008 226.3’066—dc22 2008009736 ISSN 0928-0731 ISBN 978 90 04 16774 2 Copyright 2008 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Devin Townsend Epicloud Rar

Devin Townsend Epicloud Rar 1 / 4 Devin Townsend Epicloud Rar 2 / 4 3 / 4 Check out Epicloud by Devin Townsend Project on Amazon Music. Stream ad-free or purchase CD's and MP3s now on Amazon.com.. Read {MP3 ZIP} Download Epicloud by Devin Townsend Proje from the story Meteor by minbu2018 with 6 reads. pocket, spoon, garden. Simple Way to Listen .... Devin Townsend Project. Epicloud. 01. Effervescent! 02. True North 03. Lucky Animals 04. Liberation 05. Where We Belong 06. Save Our Now. "DEVIN TOWNSEND PROJECT" fue previsto para una serie de cuatro álbumes. ... 2012 - EPICLOUD ... cual es la contraseña de los rar??. Epicloud is the fifteenth studio album by Canadian musician Devin Townsend, and the fifth album in the Devin Townsend Project series. The album was .... Название: Devin Townsend Project - Epicloud (2012), Atmospheric ... c744c19a18782551adb894126d21fd1/DTPE(metalarea.org).rar.html). DEVIN TOWNSEND announces new album 'Empath' ... I'd like to make the art available for people to download and print if they'd like… to make it complete .... Devin Townsend Epicloud Rar > http://urlin.us/3qaom Devin Townsend Epicloud Rar 056d9d66da However, this is not new territory for .... DEVIN TOWNSEND PROJECT Releases New Album EPICLOUD ... and digital download on iTunes with two exclusive bonus tracks, “Cry .... Watch the video for Angel from Devin Townsend Project's Epicloud for free, and see the artwork, lyrics and similar artists.. Here you can download Album - Epicloud 2012 by Devin Townsend. You can buy Album - Epicloud - Devin Townsend. Listen online top songs Devin .... Deluxe two CD edition includes bonus CD containing 10 demos. -

Nr Kat Artysta Tytuł Title Supplement Nośnik Liczba Nośników Data

nr kat artysta tytuł title nośnik liczba data supplement nośników premiery 9985841 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us black LP+CD LP / Longplay 2 2015-10-30 9985848 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2015-10-30 88697636262 *NSYNC The Collection CD / Longplay 1 2010-02-01 88875025882 *NSYNC The Essential *NSYNC Essential Rebrand CD / Longplay 2 2014-11-11 88875143462 12 Cellisten der Hora Cero CD / Longplay 1 2016-06-10 88697919802 2CELLOSBerliner Phil 2CELLOS Three Language CD / Longplay 1 2011-07-04 88843087812 2CELLOS Celloverse Booklet Version CD / Longplay 1 2015-01-27 88875052342 2CELLOS Celloverse Deluxe Version CD / Longplay 2 2015-01-27 88725409442 2CELLOS In2ition CD / Longplay 1 2013-01-08 88883745419 2CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb DVD-V / Video 1 2013-11-05 88985349122 2CELLOS Score CD / Longplay 1 2017-03-17 0506582 65daysofstatic Wild Light CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 0506588 65daysofstatic Wild Light Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 88985330932 9ELECTRIC The Damaged Ones CD Digipak CD / Longplay 1 2016-07-15 82876535732 A Flock Of Seagulls The Best Of CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88883770552 A Great Big World Is There Anybody Out There? CD / Longplay 1 2014-01-28 88875138782 A Great Big World When the Morning Comes CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-13 82876535502 A Tribe Called Quest Midnight Marauders CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 82876535512 A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Travels And CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88875157852 A Tribe Called Quest People'sThe Paths Instinctive Of Rhythm Travels and the CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-20 82876535492 A Tribe Called Quest ThePaths Low of RhythmEnd Theory (25th Anniversary CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88985377872 A Tribe Called Quest We got it from Here.. -

A Monster Is Coming! Free

FREE A MONSTER IS COMING! PDF David L Harrison,Hans Wilhelm | 32 pages | 22 Feb 2011 | Random House USA Inc | 9780375866777 | English | New York, United States Is Monster Hunter Rise Coming to PC? Answered The track was released on 5 June in the UK and subsequently reached No. It is The Automatic's highest charting single to date in the United Kingdom. The track's music was composed by James Frost and Robin Hawkinswith the original incarnation featuring a different chorus, both musically and lyrically. However the band decided first to change the music before deciding to rewrite the chorus's lyrics. The chorus was planned to have a fairytale- esque theme to it, with keyboardist and vocalist A Monster Is Coming! Pennie penning the idea which would become the track's famous lyric "What's that coming over the hill? Is it a monster? Originally however, the lyric was used just to fill the chorus until a more suitable A Monster Is Coming! was A Monster Is Coming!, but over time the lyric stuck and so was eventually used when the band recorded a demo of it in Many of the lyrics used in "Monster" are metaphors for drug and drink intoxication; "brain fried tonight through misuse" and "without these pills you're let loose"with the chorus 'monster' lyric A Monster Is Coming! a metaphor for the monster that comes out when people are intoxicated. The original demo of "Monster" featured more prominent synthesizers, with some different vocals, including more gang vocals during the chorus and distorted backing vocals during the verses and bridge. -

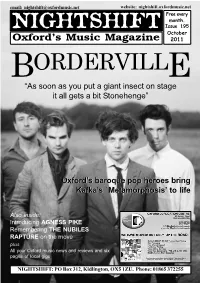

Issue 195.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 195 October Oxford’s Music Magazine 2011 BORDERVILLE “As soon as you put a giant insect on stage it all gets a bit Stonehenge” Oxford’sOxford’s baroquebaroque poppop heroesheroes bringbring Kafka’sKafka’s `Metamorphosis’`Metamorphosis’ toto lifelife Also inside: Introducing AGNESS PIKE Remembering THE NUBILES RAPTURE on the move plus All your Oxford music news and reviews and six pages of local gigs NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Truck Store is set to bow out with a weekend of live music on the 1st and 2nd October. Check with the shop for details. THE SUMMER FAYRE FREE FESTIVAL due to be held in South Park at the beginning of September was cancelled two days beforehand TRUCK STORE on Cowley Road after the organisers were faced with is set to close this month and will a severe weather warning for the be relocating to Gloucester Green weekend. Although the bad weather as a Rapture store. The shop, didn’t materialise, Gecko Events, which opened back in February as based in Milton Keynes, took the a partnership between Rapture in decision to cancel the festival rather Witney and the Truck organisation, than face potentially crippling will open in the corner unit at losses. With the festival a free Gloucester Green previously event the promoters were relying on bar and food revenue to cover occupied by Massive Records and KARMA TO BURN will headline this year’s Audioscope mini-festival. -

Nr Kat EAN Code Artist Title Nośnik Liczba Nośników Data Premiery Repertoire 19075816441 190758164410 '77 Bright Gloom Vinyl

nr kat EAN code artist title nośnik liczba nośników data premiery repertoire 19075816441 190758164410 '77 Bright Gloom Vinyl Longplay 33 1/3 2 2018-04-27 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 19075816432 190758164328 '77 Bright Gloom CD Longplay 1 2018-04-27 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 9985848 5051099858480 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us CD Longplay 1 2015-10-30 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 88697636262 886976362621 *NSYNC The Collection CD Longplay 1 2010-02-01 POP 88875025882 888750258823 *NSYNC The Essential *NSYNC CD Longplay 2 2014-11-11 POP 19075906532 190759065327 00 Fleming, John & Aly & Fila Future Sound of Egypt 550 CD Longplay 2 2018-11-09 DISCO/DANCE 88875143462 888751434622 12 Cellisten der Berliner Philharmoniker, Die Hora Cero CD Longplay 1 2016-06-10 CLASSICAL 88697919802 886979198029 2CELLOS 2CELLOS CD Longplay 1 2011-07-04 CLASSICAL 88843087812 888430878129 2CELLOS Celloverse CD Longplay 1 2015-01-27 CLASSICAL 88875052342 888750523426 2CELLOS Celloverse CD Longplay 2 2015-01-27 CLASSICAL 88725409442 887254094425 2CELLOS In2ition CD Longplay 1 2013-01-08 CLASSICAL 19075869722 190758697222 2CELLOS Let There Be Cello CD Longplay 1 2018-10-19 CLASSICAL 88883745419 888837454193 2CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb DVD Video Longplay 1 2013-11-05 CLASSICAL 88985349122 889853491223 2CELLOS Score CD Longplay 1 2017-03-17 CLASSICAL 88985461102 889854611026 2CELLOS Score (Deluxe Edition) CD Longplay 2 2017-08-25 CLASSICAL 19075818232 190758182322 4 Times Baroque Caught in Italian Virtuosity CD Longplay 1 2018-03-09 CLASSICAL 88985330932 889853309320 9ELECTRIC The Damaged Ones -

Personal Music Collection

Christopher Lee :: Personal Music Collection electricshockmusic.com :: Saturday, 25 September 2021 < Back Forward > Christopher Lee's Personal Music Collection | # | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | | DVD Audio | DVD Video | COMPACT DISCS Artist Title Year Label Notes # Digitally 10CC 10cc 1973, 2007 ZT's/Cherry Red Remastered UK import 4-CD Boxed Set 10CC Before During After: The Story Of 10cc 2017 UMC Netherlands import 10CC I'm Not In Love: The Essential 10cc 2016 Spectrum UK import Digitally 10CC The Original Soundtrack 1975, 1997 Mercury Remastered UK import Digitally Remastered 10CC The Very Best Of 10cc 1997 Mercury Australian import 80's Symphonic 2018 Rhino THE 1975 A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships 2018 Dirty Hit/Polydor UK import I Like It When You Sleep, For You Are So Beautiful THE 1975 2016 Dirty Hit/Interscope Yet So Unaware Of It THE 1975 Notes On A Conditional Form 2020 Dirty Hit/Interscope THE 1975 The 1975 2013 Dirty Hit/Polydor UK import {Return to Top} A A-HA 25 2010 Warner Bros./Rhino UK import A-HA Analogue 2005 Polydor Thailand import Deluxe Fanbox Edition A-HA Cast In Steel 2015 We Love Music/Polydor Boxed Set German import A-HA East Of The Sun West Of The Moon 1990 Warner Bros. German import Digitally Remastered A-HA East Of The Sun West Of The Moon 1990, 2015 Warner Bros./Rhino 2-CD/1-DVD Edition UK import 2-CD/1-DVD Ending On A High Note: The Final Concert Live At A-HA 2011 Universal Music Deluxe Edition Oslo Spektrum German import A-HA Foot Of The Mountain 2009 Universal Music German import A-HA Hunting High And Low 1985 Reprise Digitally Remastered A-HA Hunting High And Low 1985, 2010 Warner Bros./Rhino 2-CD Edition UK import Digitally Remastered Hunting High And Low: 30th Anniversary Deluxe A-HA 1985, 2015 Warner Bros./Rhino 4-CD/1-DVD Edition Boxed Set German import A-HA Lifelines 2002 WEA German import Digitally Remastered A-HA Lifelines 2002, 2019 Warner Bros./Rhino 2-CD Edition UK import A-HA Memorial Beach 1993 Warner Bros. -

Devin Townsend Epicloud Rar

Devin Townsend Epicloud Rar 1 / 4 Devin Townsend Epicloud Rar 2 / 4 3 / 4 Epicloud is the fifteenth studio album by Canadian musician Devin Townsend, and the fifth album in the Devin Townsend Project series. The album was .... Although I don't think Devin Townsend's Project series has ever come close to matching the jaw-dropping quality of his masterpiece “Terria”, it's exciting to hear .... DEVIN TOWNSEND PROJECT Releases New Album EPICLOUD ... and digital download on iTunes with two exclusive bonus tracks, “Cry .... Read {MP3 ZIP} Download Epicloud by Devin Townsend Proje from the story Meteor by minbu2018 with 6 reads. pocket, spoon, garden. Simple Way to Listen .... Here you can download Album - Epicloud 2012 by Devin Townsend. You can buy Album - Epicloud - Devin Townsend. Listen online top songs Devin .... Devin Townsend Epicloud Rar > http://urlin.us/3qaom Devin Townsend Epicloud Rar 056d9d66da However, this is not new territory for .... Devin Townsend Project: Epicloud is a music studio album recording by DEVIN ... free MP3 download (stream), buy online links: amazon, ratings and detailled .... r/DevinTownsend: Heavy Devy fans, get in here! This is a place for everything related to DEVIN TOWNSEND and his projects/bands --- Visit …. Название: Devin Townsend Project - Epicloud (2012), Atmospheric ... c744c19a18782551adb894126d21fd1/DTPE(metalarea.org).rar.html). DEVIN TOWNSEND announces new album 'Empath' ... I'd like to make the art available for people to download and print if they'd like… to make it complete .... "DEVIN TOWNSEND PROJECT" fue previsto para una serie de cuatro álbumes. ... 2012 - EPICLOUD ... cual es la contraseña de los rar??. Epicloud. -

2019-Legionnaire-Summer-BW.Pdf

The American Legion 720 Lyon Street, Des Moines, Iowa 50309 Iowa Moines, Des Street, Lyon 720 Department of Iowa and Legionnaire Iowa The Iowa Legionnaire & Auxiliary Communiqué Communiqu An Official Publication of The American Legion, Department of Iowa: June 2019 é Call For Convention on Page 6 with Schedule on Page 15 U.S. POSTAGE PAID POSTAGE U.S. Dubuque County Repeats NONPROFIT ORG. WEBSTER CITY, IA WEBSTER CITY, PERMIT #27 Spring is in the air, we hope it stays, and we are quickly heading into Iowa Summer. Along with the many activities that families and individuals enjoy, America’s favorite pastime of baseball is in full swing (pun intended). American Legion Baseball in Iowa had a challenging start to an early season Deadlines & Dates June 8 due to unpredictable weather. Many of the post Membership Meeting - Dept. HQ sponsored teams did not have the opportunity Aspen Dental Day of Service - Various to play as many games due to some form of June 9-14 Central Plains Regionals August 7-11, 2019, in Sioux Falls, South Boys State - Camp Dodge - Johnston precipitation or its aftermath on fields. Nevertheless, teams Dakota. The winner from that regional tournament will move on June 11 kept their resolve and The Department of Iowa had four Area Legionnaire’s Day - Camp Dodge to play in the American Legion Baseball World Series hosted in Tournaments to determine which teams had their opportunity June 15 Shelby, North Carolina August 15-20, 2019. Consolidated Post Reports Due to play in the Department Tournament, May 4-5, 2019 in Sioux The Proctor brothers were in attendance, Legionnaire of the Year Nominations Due City. -

Jaimeo Brown Takes Jazz to Church

A DIXON KIT $ WIN VALUED OVER 9,250 • DRUM-OFF FINALS • ZZ TOP THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE June 2014 The Rhythm of Hot The Voice New Gear! 150+ Photos From Winter Nate NAMM Morton Jaimeo Brown Takes Jazz to Church Steve Goulding Pub-Rocking Hollywood MODERNDRUMMER.com GEARING UP WITH THE EAGLES’ SCOTT CRAGO ON REVIEW: PORK PIE ROSEWOOD/ZEBRAWOOD KIT JAZZ DRUMMER’S WORKSHOP: SYNCOPATION REVISITED STANDING OUT NEVER SOUNDED SO GOOD Orange County Drum and Percussion Venice kits continue OCDP’s legacy of high-performance drum kits, offering lots of loud, tons of tone, and no-compromise features so you can play your best. Features like 45-degree bearing edges for sharp attack, 20 kick drum lugs for precise tuning, and OCDP’s standard suspension system for full tone and natural resonance make these Venice kits ideal for any musical genre. © 2014 OCDP Available at these preferred resellers. VENICE KIT in TUSCAN RED (also available in DESERT SAND) Your Passion. Our Commitment. Helping musicians for over 30 years. Over 85,000 Unique Products. Free Shipping, No Minimum. 45-Day Returns. 45-Day Lowest Price Guarantee. Call 855-272-1088 musiciansfriend.com JASONBITTNER SHADOWS FALL IT STARTS HERE. “During my formative years, one of my first kits was a Pearl Export. I learned how to play on it, jammed in a few of my first bands with it, and now many years later I teach my own students on a new Pearl Export kit, and it still lights me up when I hear them! I’ve played every brand of drums out there and now I’ve come home to where it all started.. -

The Death Ship by B

The Death Ship by B. Traven (Originally written in English in 1923 or 1924, translated into German by B. Traven himself and first published as Das Totenschiff.Die Geschichte eines amerikanischen Seemanns in Berlin, 1926. The first edition in English appeared in 1934) Song of an American Sailor Now stop that crying, honey dear, The Jackson Square remains still here In sunny New Orleans In lovely Louisiana. She thinks me buried in the sea, No longer does she wait for me In sunny New Orleans In lovely Louisiana. The death ship is it I am in, All I have lost, nothing to win So far off sunny New Orleans So far off lovely Louisiana. 2 THE FIRST BOOK 3 1 We had brought, in the holds of the S.S. Tuscaloosa, a full cargo of cotton from New Orleans to Antwerp. The Tuscaloosa was a fine ship, an excellent ship, true and honest down to the bilge. First-rate freighter. Not a tramp. Made in the United States of America. Home port New Orleans. Oh, good old New Orleans, with your golden sun above you and your merry laughter within you! So unlike the frosty towns of the Puritans with their sour faces of string-savers. What a ship the Tuscaloosa was! The swellest quarters for the crew you could think of. There was a great shipbuilder indeed. A man, an engineer, an architect who for the first time in the history of shipbuilding had the communistic idea that the crew of a freighter might consist of human beings, not merely of hands.