Saint Columba's Avian Pilgrim: the Grus in Irish Hagiography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Liturgical Year 2020 of the Celtic Orthodox Church Wednesday 1St

Liturgical Year 2020 of the Celtic Orthodox Church Wednesday 1st January 2020 Holy Name of Jesus Circumcision of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ Basil the Great, Bishop of Caesarea of Palestine, Father of the Church (379) Beoc of Lough Derg, Donegal (5th or 6th c.) Connat, Abbess of St. Brigid’s convent at Kildare, Ireland (590) Ossene of Clonmore, Ireland (6th c.) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 3:10-19 Eph 3:1-7 Lk 6:5-11 Holy Name of Jesus: ♦ Vespers: Ps 8 and 19 ♦ 1st Nocturn: Ps 64 1Tm 2:1-6 Lk 6:16-22 ♦ 3rd Nocturn: Ps 71 and 134 Phil 2:6-11 ♦ Matins: Jn 10:9-16 ♦ Liturgy: Gn 17:1-14 Ps 112 Col 2:8-12 Lk 2:20-21 ♦ Sext: Ps 53 ♦ None: Ps 148 1 Thursday 2 January 2020 Seraphim, priest-monk of Sarov (1833) Adalard, Abbot of Corbie, Founder of New Corbie (827) John of Kronstadt, priest and confessor (1908) Seiriol, Welsh monk and hermit at Anglesey, off the coast of north Wales (early 6th c.) Munchin, monk, Patron of Limerick, Ireland (7th c.) The thousand Lichfield Christians martyred during the reign of Diocletian (c. 333) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:1-6 Eph 3:8-13 Lk 8:24-36 Friday 3 January 2020 Genevieve, virgin, Patroness of Paris (502) Blimont, monk of Luxeuil, 3rd Abbot of Leuconay (673) Malachi, prophet (c. 515 BC) Finlugh, Abbot of Derry (6th c.) Fintan, Abbot and Patron Saint of Doon, Limerick, Ireland (6th c.) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:7-14a Eph 3:14-21 Lk 6:46-49 Saturday 4 January 2020 70 Disciples of Our Lord Jesus Christ Gregory, Bishop of Langres (540) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:14b-20 Eph 4:1-16 Lk 7:1-10 70 Disciples: Lk 10:1-5 2 Sunday 5 January 2020 (Forefeast of the Epiphany) Syncletica, hermit in Egypt (c. -

The Lives of the Saints of His Family

'ii| Ijinllii i i li^«^^ CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Cornell University Libraru BR 1710.B25 1898 V.16 Lives of the saints. 3 1924 026 082 689 The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924026082689 *- ->^ THE 3Ltt3e0 of ti)e faints REV. S. BARING-GOULD SIXTEEN VOLUMES VOLUME THE SIXTEENTH ^ ^ «- -lj« This Volume contains Two INDICES to the Sixteen Volumes of the work, one an INDEX of the SAINTS whose Lives are given, and the other u. Subject Index. B- -»J( »&- -1^ THE ilttieg of tt)e ^amtsi BY THE REV. S. BARING-GOULD, M.A. New Edition in i6 Volumes Revised with Introduction and Additional Lives of English Martyrs, Cornish and Welsh Saints, and a full Index to the Entire Work ILLUSTRATED BY OVER 400 ENGRAVINGS VOLUME THE SIXTEENTH LONDON JOHN C. NIMMO &- I NEW YORK : LONGMANS, GREEN, CO. MDCCCXCVIII I *- J-i-^*^ ^S^d /I? Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson &' Co. At the Ballantyne Press >i<- -^ CONTENTS The Celtic Church and its Saints . 1-86 Brittany : its Princes and Saints . 87-120 Pedigrees of Saintly Families . 121-158 A Celtic and English Kalendar of Saints Proper to the Welsh, Cornish, Scottish, Irish, Breton, and English People 159-326 Catalogue of the Materials Available for THE Pedigrees of the British Saints 327 Errata 329 Index to Saints whose Lives are Given . 333 Index to Subjects . ... 364 *- -»J< ^- -^ VI Contents LIST OF ADDITIONAL LIVES GIVEN IN THE CELTIC AND ENGLISH KALENDAR S. -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 74/Thursday, April 16, 2020/Notices

21262 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 74 / Thursday, April 16, 2020 / Notices acquisition were not included in the 5275 Leesburg Pike, Falls Church, VA Comment (1): We received one calculation for TDC, the TDC limit would not 22041–3803; (703) 358–2376. comment from the Western Energy have exceeded amongst other items. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Alliance, which requested that we Contact: Robert E. Mulderig, Deputy include European starling (Sturnus Assistant Secretary, Office of Public Housing What is the purpose of this notice? vulgaris) and house sparrow (Passer Investments, Office of Public and Indian Housing, Department of Housing and Urban The purpose of this notice is to domesticus) on the list of bird species Development, 451 Seventh Street SW, Room provide the public an updated list of not protected by the MBTA. 4130, Washington, DC 20410, telephone (202) ‘‘all nonnative, human-introduced bird Response: The draft list of nonnative, 402–4780. species to which the Migratory Bird human-introduced species was [FR Doc. 2020–08052 Filed 4–15–20; 8:45 am]‘ Treaty Act (16 U.S.C. 703 et seq.) does restricted to species belonging to biological families of migratory birds BILLING CODE 4210–67–P not apply,’’ as described in the MBTRA of 2004 (Division E, Title I, Sec. 143 of covered under any of the migratory bird the Consolidated Appropriations Act, treaties with Great Britain (for Canada), Mexico, Russia, or Japan. We excluded DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 2005; Pub. L. 108–447). The MBTRA states that ‘‘[a]s necessary, the Secretary species not occurring in biological Fish and Wildlife Service may update and publish the list of families included in the treaties from species exempted from protection of the the draft list. -

Spatio-Temporal Use of the Urban Habitat by Feral Pigeons (Columba Livia)

Spatio-temporal Use of the Urban Habitat by Feral Pigeons (Columba livia) Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Würde eines Doktors der Philosophie vorgelegt der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Basel von Eva Rose aus St-Sulpice (NE), Schweiz Basel, 2005 Genehmigt von der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät auf Antrag von Prof. Dr. Peter Nagel, Institut für Natur-, Landschafts- und Umweltschutz Prof. Dr. Daniel Haag-Wackernagel, Integrative Biologie, Anatomisches Institut PD Dr. Jakob Zinsstag, Schweizerisches Tropeninstitut Basel, den 8.2.2005 Prof. Dr. Hans-Jakob Wirz, Dekan Diese Arbeit wurde geleitet von: Prof. Dr. Daniel Haag-Wackernagel Forschungsgruppe Integrative Biologie Anatomisches Institut Departement Klinisch-Biologische Wissenschaften Universität Basel und Prof. Dr. Peter Nagel Institut für Natur-, Landschafts- und Umweltschutz Universität Basel Die Dissertation wurde von der Freiwilligen Akademischen Gesellschaft Basel unterstützt. Table of Contents Abstract......................................................................................................................1 Zusammenfassung.....................................................................................................3 Résumé......................................................................................................................5 Chapter 1 General Introduction...................................................................................................7 Chapter 2 Suitability of Using the -

Cury Gunwalloe

' ‘ CH U RCH ES AN D AN T I Q U I I I ES WALLO E C U RY G U N , C IN THE LI ZARD DISTRI T, I NCLUDI N G L O C A L T R A D I T I O N S . U MM I N GS ALFRED HAYMAN F , E R . ' the B ti h ha lo i l s tion i r a t Paul J Tram q/ ri s A w c g m As ocia ; V ca f s . , . te r n l and la Vica q/Cmy and Gu mal ac. E h R BORO H CO . LON DON . MA L U G , W. E R RO. LAK , T U TH E RI GHT REVEREND FREDERI CK R I P T LO D B SH O OF H E DI OCESE, OF W I U AN D GU W LL M A PART H CH C RY N A OE FOR , TH I S EFFORT TO PRESERVE SOM E OF TH E ANCI ENT TRADI TI ONS OF WEST CORNWALL I S AFFECTI ONATELY AN D RES PECTFU LLY DEDI CATED BY TH E A U T H OR. 4 0 1 0 1 0 O N C TE N TS . Saint Corantyn Cury Church Restoration of the Church B ochym Ancient Stone I mplements and Celtic Remains B onyth on Antiquities of Cury and Gunwalloe Cury Great Tree Saint Winwaloe Gunwalloe Church Wreck s Wreck of the Coquette The Dollar Wreck H oly Well at Gunwalloe The Caerth of Camden Reminiscences of the C ornish Language West Country Folk The Supernatural Traditions and Old Customs Manor of Wynyanton Looe Pool Whereby may be discerned that so fervent was the zeal of those ' elder times to ods service and honour that the freel endowed G , y y the Church with some part of their possessions and that in those ood works ev en the meaner sort of men as we as the ious g , ll p ” ’ o nders w —D u d s A i uit f u ere not bac ward. -

Then Arthur Fought the MATTER of BRITAIN 378 – 634 A.D

Then Arthur Fought THE MATTER OF BRITAIN 378 – 634 A.D. Howard M. Wiseman Then Arthur Fought is a possible history centred on a possi- bly historical figure: Arthur, battle-leader of the dark-age (5th- 6th century) Britons against the invading Anglo-Saxons. Writ- ten in the style of a medieval chronicle, its events span more than 250 years, and most of Western Europe, all the while re- specting known history. Drawing upon hundreds of ancient and medieval texts, Howard Wiseman mixes in his own inventions to forge a unique conception of Arthur and his times. Care- fully annotated, Then Arthur Fought will appeal to anyone in- terested in dark-age history and legends, or in new frameworks for Arthurian fiction. Its 430 pages include Dramatis Personae, genealogies, notes, bibliography, and 20 maps. —— Then Arthur Fought is an extraordinary achievement. ... An absorbing introduction to the history and legends of the period [and] ... a fascinating synthesis. — from the Foreword by Patrick McCormack, author of the Albion trilogy. —— A long and lavishly detailed fictional fantasia on the kind of primary source we will never have for the Age of Arthur. ... soaringly intelligent and, most unlikely of all, hugely entertaining. It is a stunning achievement, enthusiastically recommended. — Editor’s Choice review by Steve Donoghue, Indie Reviews Editor, Historical Novel Society. Contents List of Figures x Foreword, by Patrick McCormack xi Preface, by the author xv Introduction: history, literature, and this book xix Dramatis Personae xxxi Genealogies xxxix -

The Pigeon Names Columba Livia, ‘C

Thomas M. Donegan 14 Bull. B.O.C. 2016 136(1) The pigeon names Columba livia, ‘C. domestica’ and C. oenas and their type specimens by Thomas M. Donegan Received 16 March 2015 Summary.—The name Columba domestica Linnaeus, 1758, is senior to Columba livia J. F. Gmelin, 1789, but both names apply to the same biological species, Rock Dove or Feral Pigeon, which is widely known as C. livia. The type series of livia is mixed, including specimens of Stock Dove C. oenas, wild Rock Dove, various domestic pigeon breeds and two other pigeon species that are not congeners. In the absence of a plate unambiguously depicting a wild bird being cited in the original description, a neotype for livia is designated based on a Fair Isle (Scotland) specimen. The name domestica is based on specimens of the ‘runt’ breed, originally illustrated by Aldrovandi (1600) and copied by Willughby (1678) and a female domestic specimen studied but not illustrated by the latter. The name C. oenas Linnaeus, 1758, is also based on a mixed series, including at least one Feral Pigeon. The individual illustrated in one of Aldrovandi’s (1600) oenas plates is designated as a lectotype, type locality Bologna, Italy. The names Columba gutturosa Linnaeus, 1758, and Columba cucullata Linnaeus, 1758, cannot be suppressed given their limited usage. The issue of priority between livia and domestica, and between both of them and gutturosa and cucullata, requires ICZN attention. Other names introduced by Linnaeus (1758) or Gmelin (1789) based on domestic breeds are considered invalid, subject to implicit first reviser actions or nomina oblita with respect to livia and domestica. -

The Lives of the Saints. with Introd. and Additional Lives of English Martyrs, Cornish, Scottish, and Welsh Saints, and a Full I

* -* This Volume ronttiim Two Indices to the Sixteen Volumes of the work, one an Index of the Saints whose Lives are given, ami the other a Subject Index. First Edition fiiHished rSyj Second Edition , iSgy .... , New and Hevised Kditioti, i6 vols. ,, i9^'t- *- Appendix Vol. , Fronlispiece.j ^^^' * ' * THE 5LitiC0 of t|)c ^aint0 BY THE REV. S. BARINCJ-GOUU:), M.A. With Introduction and Additional Lives of English Martyrs, Cornish, Scottish, and Welsh Saints, and a full Index to the Entire Work New and Revised Edition ILLUSTRATED BY 473 ENGRAVINGS VOLUME THE SIXTEENTH SlppruDix Foluiuf EDINBURGH: JOHN GRANT 31 GEORGE IV BRIDGE 1914 * * BX 63 \ OjlLf Printed liy BAi.t.ANiVNK, Hanson »V Co. at the Dallaitlync Press, ICJinljurgh I *- -* CONTENTS PAGHS The Celtic Church and its Saints . 1-86 Brittany : its Pkincks and Saints . Pi uiGREES OF Saintly Families .... A Celtic and Eni;lish Kalendar of Saints Proper to the Welsh, Cornish, Scottish, Irish, Breton, and English People . Catalogue of the Materials Available for THE Pedigrees of the British Saints Err.\ta Index to Saints whose Lives are Given Index to Subjects -* VI Contents LIST OF ADDITIONAL LIVES C.IVEN IN THE CELTIC AND ENGLISH KALENDAR S, Calhvcn 288 S. Aaron 245 Cano}; 279 „ Ai'lliaiani .... 288 Caranoy or Carantoji 222 „ Alan 305 Caron '93 „ Aidan 177 Callian ., Albuiga .... 324 Calliciinc Aiidlcy 314 „ Alilalc 179 Cawrdaf 319 „ Alfred tlie Great . 285 Ceachvalla 213 „ Alfric 305 Ceitlio . 287 „ Alnicdlia .... 258 Cclynin, son of „ Aniacllilu .... 325 Cynyr F irfdrwcli 287 „ Arniel 264 Celynin, son of „ Arniilf 268 Ilelig 3'o „ Austell 243 Cewydd 245 „ Auxilius . -

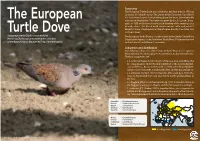

The European Turtle Dove Was Named for the First Time in 1758 by Linnaeus As Columba Turtur

Taxonomy The European Turtle Dove was named for the first time in 1758 by Linnaeus as Columba turtur. The genus of the European Turtle Dove has had several name changes throughout the years, but eventually The European was named Streptopelia. This name was given by Carolo Luciano Bona- parte in 1855 and is based on the neck drawing of the many species of turtle doves. The Greek word streptos means collar and peleia is Greek for dove. Streptopelia can therefore be directly translated into Turtle Dove ‘collared doves’. Text composed by Charles van de Kerkhof The European Turtle Dove is closely related to the Dusky Turtle Dove Photos by Charles van de Kerkhof in the collection (Streptopelia lugens), to the Adamawa Turtle Dove (S. hypopyrrha) and of the Natural History Museum at Tring, United Kingdom to the Oriental Turtle Dove (S. orientalis). Subspecies and distribution Currently four subspecies of the European Turtle Dove are recognised, the previously described subspecies isabellina is included in rufescens. The four subspecies are: • S. t. turtur (Linnaeus, 1758) is found in Europe, Asia and Africa, the breeding grounds stretch from Great Britain in the west to Kazakh- stan in the east, Russia in the north to the North-African Mediter- ranean cost in the south, including Madeira and the Canary Islands. • S. t. arenicola (Hartert, 1894) is found in Africa and Asia, from Mo- rocco to Tripoli and from Iraq and Iran to north-western China in the east. • S. t. hoggara (Geyr von Schweppenburg, 1916) is found in Africa, in the Hoggar mountains in Algeria and the Aïr mountains in Niger. -

Of the Mascarene Islands, with Three New Species

Zootaxa 3124: 1–62 (2011) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2011 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) ZOOTAXA 3124 Systematics, morphology, and ecology of pigeons and doves (Aves: Columbidae) of the Mascarene Islands, with three new species JULIAN PENDER HUME Correspondence Address: Bird Group, The Department of Zoology, Natural History Museum, Akeman St, Tring, Herts HP23 6AP. E-mail: [email protected] Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by S. Olson: 11 Oct. 2011; published: 08 Dec. 2011 JULIAN PENDER HUME Systematics, morphology, and ecology of pigeons and doves (Aves: Columbidae) of the Mascarene Islands, with three new species (Zootaxa 3124) 62 pp.; 30 cm. 08 Dec. 2011 ISBN 978-1-86977-825-5 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-86977-826-2 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2011 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2011 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) 2 · Zootaxa 3124 © 2011 Magnolia Press HUME Table of contents Abstract . 3 Introduction . 3 Materials and methods . 5 Systematics . 6 Discussion . -

Periodic Status Review for the Peregrine Falcon

STATE OF WASHINGTON October 2016 Periodic Status Review for the Peregrine Falcon Mark S. Vekasy and Gerald E. Hayes Washington Department of FISH AND WILDLIFE Wildlife Program The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife maintains a list of endangered, threatened, and sensitive species (Washington Administrative Codes 232-12-014 and 232-12-011). In 1990, the Washington Wildlife Commission adopted listing procedures developed by a group of citizens, interest groups, and state and federal agencies (Washington Administrative Code 232-12-297). The procedures include how species listings will be initiated, criteria for listing and delisting, a require¬ment for public review, the development of recovery or management plans, and the periodic review of listed species. The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife is directed to conduct reviews of each endangered, threatened, or sensitive wildlife species at least every five years after the date of its listing by the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission. The periodic status reviews are designed to include an update of the species status report to determine whether the status of the species warrants its current listing status or deserves reclassification. The agency notifies the general public and specific parties who have expressed their interest to the Department of the periodic status review at least one year prior to the five-year period so that they may submit new scientific data to be included in the review. The agency notifies the public of its findings at least 30 days prior to presenting the findings to the Fish and Wildlife Commission. In addition, if the agency determines that new information suggests that the classification of a species should be changed from its present state, the agency prepares documents to determine the environmental consequences of adopting the recommendations pursuant to requirements of the State Environmental Policy Act.