Walking the 'Willett Way'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London Loop. Section 3 of 24

Transport for London. London Loop. Section 3 of 24. Jubilee Country Park to Gates Green Road, Wickham Common. Section start: Jubilee Country Park. Nearest station Petts Wood to start: Section finish: Gates Green Road, Wickham Common. Nearest station Hayes (Kent) to finish: Section distance: 9 miles (14.5 kilometres). Introduction. This section of the LOOP passes through attractive countryside with strong links to Charles Darwin who described the countryside around the village of Downe as 'the extreme verge of the world'. The walking is generally easy, but with a few longish, steep slopes, stiles and kissing gates and some small flights of steps. Much of it is through commons, parks and along tracks. There are cafes and pubs at many places along the way and you can picnic at High Elms, where there are also public toilets. The walk starts at Jubilee Country Park and finishes at Hayes station. There are several bus routes along this walk. Continues Continues on next page Directions. To get to the start of this walk from Petts Wood station exit on the West Approach side of the station and turn right at the T-junction with Queensway. Follow the street until it curves round to the left, and carry straight on down Crest View Drive. Take Tent Peg Lane on the right and keep to the footpath through the trees to the left of the car park. After 100 metres enter Jubilee Country Park, and join the LOOP. From the car park on Tent Peg Lane enter the park and at the junction of several paths and go through the gate on the left and follow the metalled path for about 150 metres, then branch left. -

Buses from St. Mary Cray

Buses from St. Mary Cray Plumstead Granville Bexley Maylands Hail & Ride Albany Blendon Crook Log Common Road Swingate Willersley Sidcup section 51 Herbert Road Lane Welling Avenue Sidcup Police Station Road Lane Drive Park Penhill Road Woolwich Beresford Square Plumstead Edison Hook Lane Halfway Street Bexleyheath Route finder for Woolwich Arsenal Common Road Cray Road Friswell Place/Broadway Shopping Centre Ship Sidcup B14 Bus route Towards Bus stops Queen Marys Hospital WOOLWICH WELLING SIDCUP R11 51 Orpington ɬ ɭ ɹ Lewisham Lewisham R1 St. Pauls Cray BEXLEYHEATH Grovelands Road Sevenoaks Way ɨ ɯ ɻ Conington Road/ High Street Lee High Road Hail & Ride section Midfield Way Woolwich Tesco Clock Tower Belmont Park 273 273 Lewisham ɦ ɩ ɯ ɼ Midfield Way Midfield Way Lewisham Manor Park St. Pauls Wood Hill N199 Breakspears Drive &KLSSHUÀHOG5RDG Croxley Green Petts Wood ɧ ɬ ɭ ɹ ɽ Mickleham Road continues to LEWISHAM Hither Green Beddington Road Chipperfield Road Sevenoaks Way B14 Bexleyheath ɦ ɩ ɯ ɻ Trafalgar Square Cotmandene Crescent Walsingham Road for Charing Cross Lee Orpington ɧ ɬ ɭ ɹ Mickleham Road The yellow tinted area includes every Mickleham Road Goose Green Close Baring Road Chorleywood Crescent bus stop up to about one-and-a-half R1 ɧ ɬ ɭ ɹ miles from St. Mary Cray. Main stops Green Street Green Marvels Lane are shown in the white area outside. ɦ ɩ ɯ ɻ St. Pauls Wood Hill Sevenoaks Way St. Pauls Cray Lewisham Hospital Brenchley Road Broomwood Road R3 Locksbottom ɶ ɽ H&R2 Dunkery Road St. Pauls Wood Hill Orpington ɷ ɼ H&R1 Chislehurst St. -

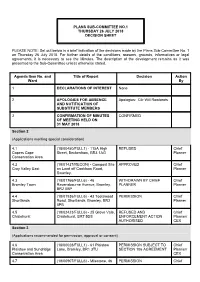

PLEASE NOTE: Set out Below Is a Brief Indication of the Decisions Made by the Plans Sub-Committee No

PLANS SUB-COMMITTEE NO.1 THURSDAY 26 JULY 2018 DECISION SHEET PLEASE NOTE: Set out below is a brief indication of the decisions made by the Plans Sub-Committee No. 1 on Thursday 26 July 2018. For further details of the conditions, reasons, grounds, informatives or legal agreements, it is necessary to see the Minutes. The description of the development remains as it was presented to the Sub-Committee unless otherwise stated. Agenda Item No. and Title of Report Decision Action Ward By 1 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST None 2 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Apologies: Cllr Will Rowlands AND NOTIFICATION OF SUBSTITUTE MEMBERS 3 CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES CONFIRMED OF MEETING HELD ON 31 MAY 2018 Section 12 (Applications submittedmeriting special by the consideration) London Borough of Bromley) 4.1 (18/00450/FULL1) - 115A High REFUSED Chief Copers Cope Street, Beckenham, BR3 1AG Planner Conservation Area 4.2 (18/01427/RECON) - Compost Site APPROVED Chief Cray Valley East on Land off Cookham Road, Planner Swanley. 4.3 (18/01766/FULL6) - 46 WITHDRAWN BY CHIEF Chief Bromley Town Ravensbourne Avenue, Bromley, PLANNER Planner BR2 0BP 4.4 (18/01936/FULL6) - 43 Tootswood PERMISSION Chief Shortlands Road, Shortlands, Bromley, BR2 Planner 0PB 4.5 (18/02423/FULL6) - 25 Grove Vale, REFUSED AND Chief Chislehurst Chislehurst, BR7 5DS ENFORCEMENT ACTION Planner/ AUTHORISED CEX Section 3 (Applications recommended for permission, approval or consent) 4.6 (18/00028/FULL1) - 61 Plaistow PERMISSION SUBJECT TO Chief Plaistow and Sundridge Lane, Bromley, BR1 3TU SECTION 106 AGREEMENT Planner/ Conservation Area CEX 4.7 (18/00907/FULL6) - Milestone, 46 PERMISSION Chief London Borough of Bromley – Decisions taken by Plans Sub-Committee No. -

Petts Wood and District RA (773).Pdf

Sadiq Khan Mayor of London Greater London Authority City Hall London SE1 28 February 2018 Dear Mr Khan/GLA Draft New London Plan team, Re: Draft New London Plan I write in my capacity as the planning representative for the Petts Wood & District Residents’ Association (PWDRA). By way of information, PWDRA represents over 3000 households in the Petts Wood & District areas of the London Borough of Bromley. The full PWDRA committee discussed aspects of the Draft New London Plan (DNLP) at out last committee meeting on 7 February 2018. As a result of our discussions, PWDRA would like to register our strong objection to certain aspects of the DNLP. Our concerns centre upon the following aspects: 1. The removal of protection for garden land. 2. The lack of protection afforded to Areas of Special Residential Character. 3. The presumption in favour of small housing development for proposals (up to 25 units) within 800 metres of a transport hub/town centre. 4. Medium residential growth potential identified for Petts Wood I will outline the PWDRA objections to each one of these points. 1. The removal of protection for garden land (Policy D4/Policy H2) This would appear to be contrary to the National Planning Framework. Secondly, in terms of our area, this would run contrary to the local designation of large areas of Petts Wood being designated an Area of Special Residential Character(ASRC) by Bromley Council. Petts Wood is Bromley Borough’s largest ASRC, designated in 1990 (please see attachments – Petts Wood ASRC descriptions from Bromley Council’s current UDP (2006) and Draft Local Plan (2017)). -

Times Are Changing at Sydenham Hill

This autumn, we’ll be running an amended weekday timetable shown below affecting Times are changing Off-Peak* metro services, but only on days when we expect the weather to be at its worst. at Sydenham Hill Check your journey up to 3 days in advance at southeasternrailway.co.uk/autumn Trains to London Mondays to Fridays There will be a minimum of 2 trains per hour Off-Peak, mainly at 18 and 48 minutes past the hour towards London. Sydenham Hill d 0518 0548 0618 0630 0650 0703 0710 0734 0740 0749 0803 0810 0817 0840 0847 0903 0910 0917 0933 0949 1003 1018 1048 1103 1118 1133 West Dulwich d 0520 0550 0620 0632 0652 0705 0712 — 0742 0752 0806 0812 0820 0842 0850 0905 0912 0920 0935 0951 1005 1020 1050 1105 1120 1135 Herne Hill a 0522 0552 0622 0634 0654 0707 0715 0737 0745 0754 0808 0815 0822 0845 0852 0907 0915 0922 0937 0953 1007 1022 1052 1107 1122 1137 Loughborough Jn d — — — — — — 0719 — 0749 — — 0819 — 0849 — — 0919 — — — — — — — — — Elephant & Castle d — — — — — — 0723 — 0753 — — 0823 — 0853 — — 0923 — — — — — — — — — London Blackfriars a — — — — — — 0729 — 0759 — — 0829 — 0859 — — 0929 — — — — — — — — — Brixton d 0526 0556 0626 0638 0658 0711 — 0741 — 0758 0812 — 0826 — 0856 0911 — 0926 0941 0957 1011 1026 1056 1111 1126 1141 London Victoria a 0535 0605 0635 0647 0707 0720 — 0750 — 0807 0821 — 0835 — 0905 0921 — 0935 0950 1004 1020 1033 1103 1118 1133 1148 Sydenham Hill d 1148 1218 1248 1518 1548 1603 1618 1648 1718 1733 1748 1803 1818 1833 1848 1918 1948 2018 2033 2048 2103 2118 2133 2148 West Dulwich d 1150 1220 1250 and at 1520 -

A British Summer Time Walk

Bromley Pub Walks A British Summer Time Walk Chislehurst to Petts Wood Station A walk through National Trust woods and farmland, focused on William Willett, the campaigner for daylight saving time. William Willett (1856-1915) the campaigner for ‘daylight saving time’ lived for much of his life in Chislehurst. Although he did not survive to see daylight saving become law, he is generally credited with bringing the idea to public attention. He is buried in St Nicholas' Churchyard in Chislehurst, there is a memorial sundial in Petts Wood (that’s the actual wood, not the suburb) and of course there is also the Daylight Inn near Petts Wood Station. Also in Petts Wood there is a road called Willett Way, and the Willett Recreation Ground. It’s possible to take a pleasant two and a quarter mile walk from Chislehurst War Memorial to Petts Wood Station (or vice-versa) which takes you past his grave, the memorial sundial and the Daylight Inn. Most of the walk is through National Trust woods and farmland. In addition to the Grade II Listed Daylight Inn, there is also the opportunity to visit the two other pubs and a club in Petts Wood, plus the many pubs in Chislehurst, two of which are directly on this walking route. In the subsequent pages we describe the route, using the standard ‘Bromley Pub Walks’ format, plus we’ve also included some photographs taken along the route. Petts Wood and Hawkwood are owned and managed by the National Trust, and most of the former Hawkwood estate is still a working farm. -

231 Poverest Road, Petts Wood, BR5 1GY Asking Price: £750,000

231 Poverest Road, Petts Wood, BR5 1GY Asking Price: £750,000 • 4 Bedroom, 2 Bathroom Detached House • Modern Fitted Kitchen/Diner • Well Located for St. Mary Cray and Petts Wood Stations • Off Street Parking Property Description Thomas Brown Estates are delighted to offer this very well presented and deceptively spacious, four bedroom two bathroom detached property, boasting flexible accommodation, walking distance to Petts Wood and St. Mary Cray Stations and close to local shops including the popular Nugent Retail Park and Petts Wood High Street. The accommodation on offer comprises: large entrance hall, lounge, modern fitted kitchen/diner with part vaulted ceiling, dining room that is open plan to the conservatory, bedroom four, utility room and WC to the ground floor. To the first floor are three spacious doubles bedrooms, family bathroom with a free standing roll top bath and a shower room with vaulted ceiling. Externally there is a rear garden mainly laid to lawn with a large decked area perfect for alfresco dining and a drive to the front for numerous vehicles. Poverest Road is well located for local schools, shops, bus routes, and St. Mary Cray and Petts Wood mainline stations. ENTRANCE HALL Opaque windows and wooden door to front, double doors to lounge, solid oak flooring, radiator. LOUNGE 16' 6" x 11' 5" (5.03m x 3.48m) (open plan to conservatory) Fireplace, two double glazed opaque windows to side, carpet, two radiators. CONSERVATORY 13' 2" x 11' 8" (4.01m x 3.56m) (open plan to dining room) Double glazed windows to rear and side, double glazed French doors to rear, tiled effect flooring, radiator. -

Cray Riverway Village

How to get there... 9 Turn left down Edgington Lane for 100 metres to a footbridge, cross and turn right to head back to the BUSES: roundabout and turn left into Maidstone Road. Walk on R6 Orpington to St Mary Cray 400 metres to Foots Cray High Street. Cross the road to Wa l k s R4 St Paul’s Cray to Locksbottom the Seven Stars public house c.1753 on the right. In 1814 51 Woolwich to Orpington a red lantern was hung outside this pub to guide travellers around the Borough 61 Chislehusrt to Bromley through the ford and it was once an important staging post for coaches from Maidstone to London. 273 Lewisham to Petts Wood R1 St Pauls Cray to Green Street Green R11 Sidcup to Green Street Green 10 Continue past the Tudor Cottages on the left to the end B14 Bexleyheath to Orpington of the High Street. Turn right into Rectory Lane, the listed R2 Petts Wood to Biggin Hill Georgian Terrace on the left c. 1737 bears the original R3 Locksbottom to Chelsfield road plaques. Continue on to Harenc School c.1815, a clock tower was added to commemorate Queen Victoria’s TRAIN: Jubilee. Nearest station: Orpington CAR: Image © David Griffiths 11 Walk on 300 metres. Ahead is the parish church of All Turn into the High Street, Orpington at the junction with Saints Foots Cray. Originally a wood and thatch building Station Road (A232). Continue north along the High c.900 AD, it was rebuilt in 1330. Take the signposted Street and turn into Church Hill. -

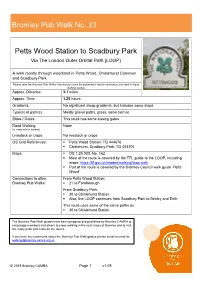

Petts Wood Station to Scadbury Park Via the London Outer Orbital Path (LOOP)

Bromley Pub Walk No. 23 Petts Wood Station to Scadbury Park Via The London Outer Orbital Path (LOOP) A walk mostly through woodland in Petts Wood, Chislehurst Common and Scadbury Park Please read the Bromley Pub Walks introductory notes for explanation about information provided in these walking guides Approx. Distance: 3.1 miles Approx. Time: 1.25 hours Gradients: No significant steep gradients, but includes some steps Type(s) of path(s): Mostly gravel paths, grass, some tarmac Stiles / Gates: This route has some kissing gates Road Walking: None (ie. roads without footway) Livestock or crops: No livestock or crops OS Grid References: . Petts Wood Station: TQ 444676 . Chislehurst, Scadbury Park: TQ 453704 Maps: . OS 1:25 000, No. 162 . Most of the route is covered by the TFL guide to the LOOP, including maps: https://tfl.gov.uk/modes/walking/loop-walk . Part of the route is covered by the Bromley Council walk guide ‘Petts Wood’ Connections to other From Petts Wood Station: Bromley Pub Walks: . 21 to Farnborough From Scadbury Park: . 30 to Chislehurst Station . Also, the LOOP continues from Scadbury Park to Bexley and Erith This route uses some of the same paths as: . 30 to Chislehurst Station The Bromley Pub Walk guides have been prepared and published by Bromley CAMRA to encourage members and others to enjoy walking in the rural areas of Bromley and to visit the many pubs and clubs on the routes. If you have any comments about the Bromley Pub Walk guides please send an email to: [email protected] © 2019 Bromley CAMRA Page 1 v1.05 Bromley Pub Walk No. -

Bromleag Magazine Index from 1974 to 2020

Bromleag Magazine Index from 1974 to 2020 Title Year Month Page Location or Subject A A21, 1950s film 2017 Dec 17 Borough wide A Disorderly Chinee 1998 Jun 13 Beckenham A Peep into History – Hilda Sibella 1994 Jun 40 Bromley College Ack-Ack guns at Petts Wood WWII 2020 Dec 29 Petts Wood/Southborough Addison Road School 2002 Mar 12 Bromley Common Air raid shelters 2005 Dec 14 Beckenham Air Raids, WWII 2011 Mar 26 Borough wide Airmail, centenary of first British flight 2002 Mar 5 Beckenham Alexandra Estate 1996 Mar 2 Beckenham/Penge Allnut, Tony retiring BBLH chairman 2015 Dec 3 Chislehurst/ BBLHS Allnut, Tony retirement presentation 2016 Jun 4 Chislehurst/BBLHS All Saint’s, Orpington, parish records 1975 May 14 Orpington All Saints old churchyard 1982 Nov 4 Orpington Allen, George 2008 Sep 16 Orpington Allen, George and Sunnyside 2015 Jun 7 Orpington Almshouses 2003 Sep 4 Penge Alms-houses 2017 Dec 12 Penge Alms-houses Bromley Road 1988 Sep 2 Bromley Ancient Order of Froth Blowers 2014 Mar 18 West Wickham Anglican Churches in Bromley 1999 Dec 22 Borough wide Anerley, history 2019 Sep 19 Anerley Anglo Saxon treasure 2010 Sep 10 Farnborough Arcadia Overwhelmed 1996 Jun 5 West Wickham Arcadia Overwhelmed 1996 May 5 West Wickham Arcadia Overwhelmed 1996 Oct 10 West Wickham Arcadia Overwhelmed 1997 Jun 9 West Wickham Arcadia Overwhelmed 1997 Mar 10 West Wickham Arcadia Overwhelmed 1997 Sep 11 West Wickham Archbishop Arnold Harris Mathew 2015 Dec 16 Chelsfield Archivist’s job 2017 Dec 10 General ARP posts in Beckenham 2006 Mar 10 Beckenham ARP -

Petts Wood 9 Station Square, Br5 1Lr Ground Floor Former Bank Premises, Approx 2443Sq.Ft

TO LET PETTS WOOD 9 STATION SQUARE, BR5 1LR GROUND FLOOR FORMER BANK PREMISES, APPROX 2443SQ.FT THE PROPERTY MISDESCRIPTIONS ACT 1991 The agent has not tested ay apparatus, equipment, fixtures and fittings or services and so cannot verify that they are in working order of fit for the purpose. Prospective Purchasers/Lessees are advised to obtain verification from their Solicitor or Surveyor. References to the tenure of this property are based on information supplied by our Clients. The Agent has not had sight of the Title Documents and prospective Purchasers/Lessees are advised to obtain verification from their Solicitor. These Particulars do not form, nor form any part of, an offer or contract. Neither Linays Commercial nor any of their employees has any authority to make or give further representations or warranties to the property. LOCATION/ DESCRIPTION ASSESSMENTS Petts Wood is located within the London Borough We are advised that the Valuation Office Agency (VOA) is of Bromley and lies to the North of Orpington and to assess the rates liability on completion of the building to the South East of Bromley. The town is well works. Prospective tenants should contact the London served for road transport with the M25 London Borough of Bromley Business Rates Department for more orbital, the M20 and the M2 within 15 minutes’ drive. information. The town is popular with commuters and Petts EPC Wood Railway Station is located approx. 100m away Details available on request. Rating E-115. providing rail connections to London Victoria, Cannon Street, Charing Cross and London Bridge. VAT VAT is applicable on rental amounts. -

Blue Plaque Chislehurst & Petts Wood

Blue Plaque Chislehurst & Petts Wood Start from Chislehurst Station, Station Approach, off Summer Hill, A222. Turn left down Station Approach. Turn right into Old Hill, then right again into Caveside Close. Bear left to the entrance to Chislehurst Caves (conducted tours; closed Mondays and Tuesdays), on the outside wall of which is a Blue Plaque recording the use of Chislehurst Caves as an overnight air raid shelter during the Second World War. Free entry to historical display area (also café and toilets). Return to Old Hill, then turn right. At the top of the hill is ‘The Cedars’ (left), a large house with a Blue Plaque to William Willett (1856-1915), noted house builder and initiator of British Summer Time. Turn left along Camden Park (private) Road. Fork left into Bonchester Close to ‘Bonchester’, on the wall of which is a Blue Plaque to Sir Malcolm Campbell, MBE (1885-1948), world land and water speed record holder, who lived at ‘Rossmore’ (now ‘West Witheridge’) in Prince Imperial Road from his birth in 1885 until 1894, and at ‘Northwood’ in Manor Park Road between 1895 and 1908. (Despite the misleading wording on the plaque, he never lived at ‘Bonchester’, his parents’ home!). Return to the end of Camden Park Road. Turn left along the drive to Camden Place, now a golf clubhouse. To the left of its entrance a rectangular white marble wall plaque inscribed in French records that Napoleon III (1808-1873) lived here from 1871 until his death in 1873, as did the Empress Eugene from 1870 until 1879 and the Prince Imperial from 1870 until 1879.