A Local Analysis of Ethnic Group Population Trends and Projections for the UK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tuberculosis in London: Annual Review (2013 Data)

Tuberculosis in London: Annual review (2013 data) Data from 1999 to 2013 Tuberculosis in London (2013) About Public Health England Public Health England exists to protect and improve the nation's health and wellbeing, and reduce health inequalities. It does this through world-class science, knowledge and intelligence, advocacy, partnerships and the delivery of specialist public health services. PHE is an operationally autonomous executive agency of the Department of Health. Public Health England Wellington House 133-155 Waterloo Road London SE1 8UG Tel: 020 7654 8000 http://www.gov.uk/phe Twitter: @PHE_uk Facebook: www.facebook.com/PublicHealthEngland Prepared by: Field Epidemiology Services (Victoria) For queries relating to this document, please contact: [email protected] © Crown copyright 2014 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v2.0. To view this licence, visit OGL or email [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to [email protected]. Published October 2014 PHE gateway number: 2014448 This document is available in other formats on request. Please call 020 8327 7018 or email [email protected] Tuberculosis in London (2013) Contents About Public Health England 2 Contents 2 Executive summary 5 Background 8 Objectives 8 Tuberculosis -

Spectral Latinidad: the Work of Latinx Migrants and Small Charities in London

The London School of Economics and Political Science Spectral Latinidad: the work of Latinx migrants and small charities in London Ulises Moreno-Tabarez A thesis submitted to the Department of Geography and Environment of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, December 2018 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 93,762 words. Page 2 of 255 Abstract This thesis asks: what is the relationship between Latina/o/xs and small-scale charities in London? I find that their relationship is intersectional and performative in the sense that political action is induced through their interactions. This enquiry is theoretically guided by Derrida's metaphor of spectrality and Massey's understanding of space. Derrida’s spectres allow for an understanding of space as spectral, and Massey’s space allows for spectres to be understood in the context of spatial politics. -

Institutionalising Diaspora Linkage the Emigrant Bangladeshis in Uk and Usa

Ministry of Expatriates’ Welfare and Overseas Employmwent INSTITUTIONALISING DIASPORA LINKAGE THE EMIGRANT BANGLADESHIS IN UK AND USA February 2004 Ministry of Expatriates’ Welfare and Overseas Employment, GoB and International Organization for Migration (IOM), Dhaka, MRF Opinions expressed in the publications are those of the researchers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an inter-governmental body, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and work towards effective respect of the human dignity and well-being of migrants. Publisher International Organization for Migration (IOM), Regional Office for South Asia House # 3A, Road # 50, Gulshan : 2, Dhaka : 1212, Bangladesh Telephone : +88-02-8814604, Fax : +88-02-8817701 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : http://www.iow.int ISBN : 984-32-1236-3 © [2002] International Organization for Migration (IOM) Printed by Bengal Com-print 23/F-1, Free School Street, Panthapath, Dhaka-1205 Telephone : 8611142, 8611766 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher. -

Download Full Publication

Pau[ Iganski Vicky Kielinger Susan Paterson 5*r KEY FINDINGS 1 KEY FINDINGS Trends in antisemitic incidents · The number of incidents recorded by the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) each month fluctuates. Peaks are commonly attributed to international political events, and especially conflicts in the Middle East and flare-ups in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Troughs indicate a pos- sible seasonal trend. · An early upward trend in recorded incidents between 1996 and 2000 may reflect a real increase in incidents, but it may be wholly or partly an artefact resulting from devel- opments in the policing of antisemitic crime by the MPS. · A downward trend in incidents since 2001 is evident, but it cannot be concluded from the police data alone whether this represents an actual decline in victimisation, espe- cially as it runs counter to the trend recorded by the Community Security Trust (CST). · Racist incidents recorded by the MPS from January 2001 to December 2004 also show a downward trend in the frequency of incidents across the four years. · An analysis of a sub-sample of antisemitic incidents re- corded by the MPS suggests that many incidents appear to be opportunistic and indirect in nature. 1 HATE CRIMES AGAINST LONDON’S JEWS Location of antisemitic incidents · One-third of antisemitic incidents are recorded as occur- ring in the London Borough of Barnet. This matches the proportion of London’s Jewish population that live in the borough. Incidents reported in Barnet, Hackney, Westminster and Camden account for just under two- thirds of all incidents reported. · Most incidents occur either at identifiably Jewish locations (such as places of worship and schools) or in public loca- tions where the victims are identifiably Jewish. -

ETHNIC MINORITIES in GREAT BRITAIN: Social and Economic Circumstances

UNIVERSITY OF WARWICK CENTRE FOR RESEARCH IN ETHNIC RELATIONS NATIONAL ETHNIC MINORITY DATA ARCHIVE 1991 Census Statistical Paper No 8 CHINESE PEOPLE AND "OTHER" ETHNIC MINORITIES IN GREAT BRITAIN: Social and economic circumstances David Owen COMMISSION FOR RACIAL EQUALITY E.-S-R--C December 1994 ECONOMIC & S C) C I A L RESEARCH COUNCIL CHINESE PEOPLE AND "OTHER" ETHNIC MINORITIES IN GREAT BRITAIN: Social and economic circumstances 1991 Census Statistical Paper no, 8 by David Owen National Ethnic Minority Data Archive Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations, December 1994 University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL. The Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations is a Research Centre of the Economic and Social Research Council. The Centre publishes a series of Research, Policy, Statistical and Occasional Papers, as well as Bibliographies and Research Monographs, The views expressed in our publications are the responsibility of the authors. The National Ethnic Minority Data Archive was established with financial support from the Commission for Racial Equality. © Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations 1994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recorded or otherwise, without the prior permission of the authors. Orders for Centre publications should be addressed to the Publications Manager, Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations, Arts Building, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL. Cheques and Postal Orders should be made payable to the University of Warwick, Please enclose remittance with order. ISSN 0969-2606 ISBN 0 948303 58 1 Acknowledgements This paper uses the Local Base Statistics from the 1991 Census of Population aggregated to the regional and Great Britain levels. -

The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

THE ROYAL BOROUGH OF KENSINGTON AND CHELSEA BOROUGH COMMUNITY RELATIONS COMMITTEE 8th FEBRUARY 2001 A REPORT BY THE COMMUNITY RELATIONS ADVISOR WITHOUT PREJUDICE: EXPLORING ETHNIC DIFFERENCES IN LONDON INTRODUCTION This report provides members with a summary of the recently compiled Greater London Authority (GLA) study which examined the differences between ethnic groups in London. FOR INFORMATION 1. METHODOLOGY 1.1 The study mainly utilised 1991 Census information. 1.2 In terms of size, “Without Prejudice” is a comprehensive 160 page study. This report will concentrate only on the study’s examination of the diversity of the London population, and of migration patterns. 1.3 The tables reproduced in this document were commissioned by the London Research Centre. 2. DEMOGRAPHY 2.1 Of the 120 countries or regions included in the study, nine of these are countries not included in the standard Census output: Country of Size of Main Boroughs of Residence Birth Community Brazil 4,630 Westminster (635), RBK&C (588) Columbia 3,991 RBK&C (454), Lambeth (444) Iraq 8,353 Ealing (1,339), Westminster (831) Jordan 909 Westminster (158), RBK&C (129) Lebanon 6,444 Westminster (1,230), RBK&C (1,206) Saudi Arabia 1,200 Westminster (212) Syria 1,505 Westminster (247), Ealing (186), RBK&C (169) Taiwan 743 Barnet (93), Westminster (74) Thailand 3,117 RBK7C (370), Westminster (249) Source: 1991 Census, LRC Commissioned Table LRCT14 2.2 Of the 6.7 million people resident in London at the time of the 1991 Census, 78% were born in the UK. 5,002,000 were born in England, 113,000 were born in Scotland, 71,000 in Wales, and 42,000 in Northern Ireland. -

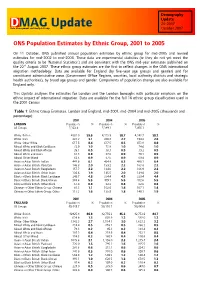

DMAG Update 20-2007 Data Management and Analysis Group October 2007

Demography Update DMAG Update 20-2007 Data Management and Analysis Group October 2007 ONS Population Estimates by Ethnic Group, 2001 to 2005 On 11 October, ONS published annual population estimates by ethnic group for mid-2005 and revised estimates for mid-2002 to mid-2004. These data are experimental statistics (ie they do not yet meet the quality criteria to be ‘National Statistics’) and are consistent with the ONS mid-year estimates published on the 22nd August 2007. These ethnic group estimates are the first to reflect changes in the ONS international migration methodology. Data are available for England (by five-year age groups and gender) and for constituent administrative areas (Government Office Regions, counties, local authority districts and strategic health authorities), by broad age groups and gender. Components of population change are also available for England only. This Update analyses the estimates for London and the London boroughs with particular emphasis on the ethnic impact of international migration. Data are available for the full 16 ethnic group classification used in the 2001 Census. Table 1: Ethnic Group Estimates, London and England, mid-2001, mid-2004 and mid-2005 (thousands and percentage) 2001 2004 2005 LONDON Population % Population % Population % All Groups 7,322.4 7,389.1 7,456.1 White: British 4363.9 59.6 4,335.9 58.7 4,342.7 58.2 White: Irish 223.7 3.1 200.8 2.7 194.2 2.6 White: Other White 617.5 8.4 627.5 8.5 653.8 8.8 Mixed: White and Black Caribbean 72.0 1.0 73.8 1.0 74.6 1.0 Mixed: White and Black -

London's Poverty Profile

London’s Poverty Profile Tom MacInnes and Peter Kenway London’s Poverty Profile Tom MacInnes and Peter Kenway www.londonspovertyprofile.org.uk A summary of this report can be downloaded in PDF format from www.londonspovertyprofile.org.uk We are happy for the free use of material from this report for non-commercial purposes provided City Parochial Foundation and New Policy Institute are acknowledged. © New Policy Institute, 2009 ISBN 1 901373 40 1 Contents 5 Foreword Acknowledgements 6 7 Introduction and summary 11 Chapter one: An overview of London London’s boroughs: ‘cities’ in their own right 11 The changing populations of Inner and Outer London 12 London’s diverse population 12 London’s age structure 15 London’s ‘sub-regions’ 16 At London’s margins 17 19 Chapter two: Income poverty Key points 19 Context 20 Headline poverty statistics, ‘before’ and ‘after’ housing costs 21 Before or after housing costs? 22 Poverty in London compared with other English regions 23 Poverty in Inner and Outer London 26 In-work poverty 27 29 Chapter three: Receiving non-work benefits Key points 29 Context 30 Working-age adults receiving out-of-work benefits 30 Children and pensioners in households receiving benefits 34 37 Chapter four: Income and pay inequality Key points 37 Context 38 Income inequality in London compared with other English regions 39 Inequalities within London boroughs 40 43 Chapter five:Work and worklessness Key points 43 Context 44 Working-age adults lacking work 45 Children in workless households 48 Lone parent employment rates 49 The -

Westminsterresearch

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch Crime and disorder Sacha Darke School of Law This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © The Author, 2007. This is a scanned reproduction of the paper copy held by the University of Westminster library. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Users are permitted to download and/or print one copy for non-commercial private study or research. Further distribution and any use of material from within this archive for profit-making enterprises or for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: (http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] lsolýl ý11ý pHD Crime and Disorder SachaDarke A thesissubmitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degreeof Doctor of Philosophy May 2007 ST COPY AVAILA L Variable print quality Abstract This thesis investigates growing use of civil and public law orders as tools of crime control by crime prevention partnerships.This development has been little explored in criminology. The proliferation of crime prevention partnerships is viewed by many criminologists as forming part of a bifurcation in criminal policy between serious crime and anti-social behaviour, in which the 'enforcement approach' of the criminal justice system is being focused upon the former and a non-legal 'partnership approach' advanced for the control of the latter. -

Projecting Employment by Ethnic Group to 2022

REPORT PROJECTING EMPLOYMENT BY ETHNIC GROUP TO 2022 David Owen, Lynn Gambin, Anne Green and Yuxin Li As the proportion of the UK population from ethnic minorities increases and the structure of employment by industrial sector and occupation changes, there is policy interest in what the future profile of employment by ethnic group could look like. This report presents projections of employment by ethnic group in 2022 and identifies challenges for policy and practice associated with access to and progression in employment. The report explores: • the faster than average growth of the working age population from ethnic minorities; • variations in labour market participation by ethnic group and gender; • ethnic group differentials in experience of professionalisation and polarisation of employment; and • the likely persistence of existing ethnic inequalities in the labour market. MARCH 2015 WWW.JRF.ORG.UK CONTENTS Executive summary 06 1 Introduction 10 2 Data and methods 13 3 The future population and labour market 18 4 Labour market participation of ethnic groups in the UK 30 5 The changing employment profile of ethnic groups 49 6 Conclusions and implications 77 Notes 82 References 83 Acknowledgements 85 About the authors 86 List of figures 1 Projected population change by five-year age group, UK 21 2 White and ethnic minority working age population in 2012 and 2022 by five-year age group: UK 22 3 Projected employment change by industry sector, 2012–22 25 4 Projected employment change by SOC Major Group, 2012–22 27 5 UK male economic activity -

Focus on London 2007 Part 4.Qxp

Focus on London 2007 © Crown copyright 2007 A National Statistics publication Published with the permission of the Controller of Her National Statistics are produced to high professional standards Majesty's Stationery Office (HMSO) set out in the National Statistics Code of Practice. They are produced free from political influence. You may re-use this publication (excluding logos) free of charge in any format for research, private study or internal circulation within an organisation. You must re-use it accurately and not use it in a misleading context. The material About the Office for National Statistics must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and you must give The Office for National Statistics (ONS) is the government the title of the source publication. Where we have identified agency responsible for compiling, analysing and disseminating any third party copyright material you will need to obtain economic, social and demographic statistics about the United permission from the copyright holders concerned. Kingdom. It also administers the statutory registration of births, This publication is also available at the National Statistics marriages and deaths in England and Wales. website: www.statistics.gov.uk The Director of ONS is also the National Statistician and the For any other use of this material please apply for a Click-Use Registrar General for England and Wales. Licence for core material at www.opsi.gov.uk/click- use/system/online/pLogin.asp or by writing to: About the Greater London Authority Office of Public Sector Information The Greater London Authority was created in 2000 as a new Information Policy Team form of strategic citywide government, consisting of an elected St Clements House Mayor and a separately elected Assembly. -

Road Safety of London's Black and Asian Minority Ethnic Groups

Road Safety of London’s Black and Asian Minority Ethnic Groups A report to the London Road Safety Unit Rebecca Steinbach, Phil Edwards Judith Green, Chris Grundy London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Table of Contents Acknowledgements 2 Summary 3 Part A: Relationships and Risks 10 1. Introduction 11 2. Methods 14 3. Results 20 3.1 Person 20 3.2 Place 24 3.3 Time 29 3.4 Multivariable analysis 32 3.5 Exposure to risk 38 4. Discussion 43 5. Recommendations 48 Appendices 49 Part B: Policy and Practice 60 1. Aims 61 2. Introduction 61 3. Methods 63 4. Findings 64 4.1 How important is the issue to BAME communities? 64 4.2 The boroughs’ perspective 65 4.3 Accounting for ethnic inequalities 70 4.4 Young people’s transport choices 73 4.5 Addressing inequalities 77 5. Discussion 79 6. Conclusion 82 References 84 1 Acknowledgements Relationships & Risks – Traffic flow and speed data were supplied by Martin Obee at Road Network Monitoring, Transport for London. The road network used was OS ITN layer supplied by Transport for London under licence and is copyright Ordnance Survey. 2001 census data were supplied with the support of ESRC and is crown copyright. Digital boundaries are Crown and OS copyright. Dale Campbell at Transport for London provided access to LATS 2001. Athanasios Nikolentzos helped with data extraction for Part B of the report. We thank those who agreed to talk with us about their views and experiences. This work was undertaken by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine who received funding from Transport for London.