10 Year Report 1996 - 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

50 Years of Oregon Senior and Disability Policy and Advocacy: an Historical Chronology 1969-2019

50 Years of Oregon Senior and Disability Policy and Advocacy: An Historical Chronology 1969-2019 By Dr. James (Jim) Davis Oregon State Council for Retired Citizens United Seniors of Oregon December 2020 0 Table of Contents Introduction Page 3 Yearly Chronology of Senior and Disability Policy and Advocacy 5 1969 5 1970 5 1971 6 1972 7 1973 8 1974 10 1975 11 1976 12 1977 13 1978 15 1979 17 1980 19 1981 22 1982 26 1983 28 1984 30 1985 32 1986 35 1987 36 1988 38 1989 41 1990 45 1991 47 1992 50 1993 53 1994 54 1995 55 1996 58 1997 60 1998 62 1999 65 2000 67 2001 68 2002 75 2003 76 2004 79 2005 80 2006 84 2007 85 2008 89 1 2009 91 2010 93 2011 95 2012 98 2013 99 2014 102 2015 105 2016 107 2017 109 2018 114 2019 118 Conclusion 124 2 50 Years of Oregon Senior and Disability Policy and Advocacy: An Historical Chronology 1969-2019 Introduction It is my pleasure to release the second edition of the 50 Years of Oregon Senior and Disability Policy and Advocacy: An Historical Chronology 1969-2019, a labor of love project that chronicles year-by-year the major highlights and activities in Oregon’s senior and disability policy development and advocacy since 1969, from an advocacy perspective. In particular, it highlights the development and maintenance of our nationally-renown community-based long term services and supports system, as well as the very strong grassroots, coalition-based advocacy efforts in the senior and disability communities in Oregon. -

1993 Fall Advancesheet

A newsletter published by Oregon Women Lawyers Volume 4, No.4 Fall1993 L::::s OREGON WOMEN 1LAWYJER§~ llllll Who He Are & Where He're Going ,~ OREGO,Nwomen By Mary Beth Allen lAW Y E R s'" hile the official genesis of Oregon them for breakfast and a discussion about form W Women Lawyers might be open to ing a statewide women's bar organization. Fol President Diana Craine debate, four of the group's founders agree on lowing that meeting, at which The Hon. Betty thesiteofits unofficial origins: KatherineO'Neil's Roberts and The Hon. Mercedes Deiz spoke, a President Elect/ Vice President living room. brainstorming Helie Rode " It was like a session was held Secretary salon," says in November at Susana A lba Nell Hoffman the state bar Treasurer Bonaparte of headquarters. Phylis Myles the experience The women de Historian Tru dy A llen ofmeetingwith cided that day to other women at form their own Board Members Colette Boehmer 0' eiJ's_hous_e..._ bar asso.ciation julie Levie Caron to discuss form to forward their jeanean West Craig ing Oregon' s goal of advanc Michele Longo Eder Susa n Eggum first statewid~ ing women and Susa n Evans Grabe women's bar minorities in the jennifer Harrington association. "A legal profession. Susa n Isaacs political, social, Oregon Kay Kinsley Trudy Allen (OWLS and Queen's Bench board member), janet Lee Knottnerus educational sa Women Lawyers Andrea Swanner Redding Regnell (Mary Leonard Society president), Kathryn Ricciardelli Kathryn Ri cciardelli lon. It was excit (outgoing OWLS president), Nancy Moriarty (Queen's Bench held its first Noreen Saltveit ingtobeinvolved president) and Loree Devery (Queen's Bench treasurer) proudly conference on Cristina Sanz with so many dy April1, 1989 in Shelley Smith show off their OWLS' shirts and mugs. -

House Concurrent Resolution 0213

OREGON LAWS 2018 HCR 213 HOUSE CONCURRENT RESOLUTION 213 city through a period of tremendous social change, growth and revitalization; and Whereas as mayor, Vera Katz championed the Whereas Vera Katz was born on August 3, 1933, arts and education, fought discrimination and cele- in Dusseldorf, Germany, to Lazar and Raissa Pistrak; brated diversity; and and Whereas Vera Katz, a TriMet user herself, was Whereas the Pistrak family left Germany for a tireless advocate for public transportation in Port- France when Vera was just two months old, and in land, leading the way to many lasting improvements, 1940 they fled invading German armies for Spain on including the Portland Streetcar; and foot over the Pyrenees Mountains, a journey that Whereas Vera Katz’s legacy as mayor can be ultimately led them to New York City; and seen all over Portland’s urban landscape, from the Whereas Vera Katz attended Brooklyn College, Pearl District to South Waterfront to the Eastbank where she studied dance under the legendary Esplanade that was named in her honor; and Martha Graham and received a degree in sociology; Whereas Vera Katz was a fierce protector of the and city she dearly loved, and she personally manned Whereas Vera Katz and her husband, Mel Katz, Portland’s sandbag brigade when the Willamette River swelled above flood stage in 1996; and moved to Portland, Oregon, in the early 1960s, where Whereas after leaving City Hall in 2005, Vera they raised their young son, Jesse; and Katz remained very active in civic life, selflessly Whereas Vera Katz first became involved in volunteering in the community and working for politics as a volunteer in Robert F. -

She Flies with Her Own Wings

Courtesy of Paulus Norma TARA WATSON AND MELODY ROSE She Flies With Her Own Wings Women in the 1973 Oregon Legislative Session DURING THE 1973 OREGON legislative session, a bipartisan group of female legislators — almost half in their first session — worked with political activists and allies in the state capitol to pass eleven explicitly feminist bills into law. That such a small number of relatively inexperienced legislators was able to pass such a substantial portion of a feminist legislative agenda Tom McCall signs equal rights legislation. Witnesses are (left to right): Senate in just one session is unprecedented in the history of the Oregon legislature President Jason Boe, Speaker of the House Richard Eyman, Secretary of State Clay Myers, Representative Nancie Fadeley (Chair of the House Environment and and is due some historical analysis. It also makes for a great story. Natural Resources Committee), Representative Norma Paulus, and Representative Oregon’s female legislators were successful in the 17 session because Grace Peck. McCall’s note on the bottom reads, “Warm thanks, Norma, for that unique window of time produced a favorable political climate, sup- championing equal rights! Gov. Tom McCall Feb, 1973.” port of the male governor and male legislators, organizational strength of Oregon’s women’s organizations, and a sense of overall optimism within the Oregon women’s movement. Because of their experience, organizational competence, and ability to work together as a woman-identified group, ORAL HISTORY TRANSCRIPTS from Norma Paulus and Betty Roberts female legislators were able to utilize this brief period of ideal conditions — both members of the legislature during the 17 session — and Gretchen to pass feminist legislation rapidly into law. -

Nificant Natural Area Sites and Interconnections

.~ ". \ i' .- / ,.• --- ./ \. \ ~ • I. • h j . .LC .' \. \ \ '.', ."'- /_ ,I • ~, I • ,{ \ I j .' ,,'" "..', r -, " (. ) ./ ..~, / / --)" ( , / '- L • r-( ."• \ " • ." L •~ rr ('., r I" ~••. / r ~ ). ," , \ . ) / ) •. ~ \ '-: '.' / -' ", ,'; ---' -, ", - ( '..\~ , " ' '. ,J \. ) .~ .\ / -" ,e.' ·r ","." ~ METROPOLITAN - e> )~ .' \ I" e :\(?-reel1space~, :- J • 'f /' r: /. ..../ .J \ • ~.' / l .. 'v' /". • '> I / I e-, ~ ./ ,I \ • .>" ) Master-Piait ) e• .,/ r ", / Ij .'-..... L e "'" '. \ e ( r e /. e e, , --- '~. e j -.', ,. ;' r .. •er, ) r / -'. ~ \' - ( . ~ . ., ~ ~' -\ A Cooperative Regio!lal$ystem ofNa.tural Areas, "Open Space, T~f!:..ils a~¢ Gree.nways / /', ' '.)' " forWilcJlife and p,!ople . ./( . ./ ,... ' .... / r • '. X- •.\ / e ! -, "e- ( \ - '- '\ .J • r~gional go~ernmeht (As' ofJuly 1992) "- (. • Metro is the 'directly elected thatserves , .. ,/ Clackamas, Multnomah and Washington cOUlities andilie 24 Policy Advisory COn:'!m,ittee M,ember;s: • \'citiesThat make up the P~rtlana metropolita~;rea. " "'- Ri~hard Devlin, Metro councilor and chair •e- Metr~is ;~spon~ible f~r soli~:~aste management, op~ration/of Ruth~cFariana, Metro,co~n;ilor rmd vice-chair ,_ .i ,'-- M~tro us~ \, the Washington Park Zoo, transportation-and land Sandi Hansen/Metro councilor " "- ~" ' pl~nping, 1da~inerstad, commissi~ne~ urban growth boundary management, technical ." J Judie Clackamas County . ,. services to local go\\ernments and, 'through the Metropolitan Pauline Anderson, Multnomah County commissioner ) r·, ) : fxposition)Recre,ation Gommission,man~gementofthe -

OJL WEB (1).Pdf

JULY 2013 SERVING OREGON AND SW WASHINGTON Denise & AnnA WEtHEREll Mother-Daughter Duo Pamper Portlanders, Aid African Refugees SPeciAl SecTiOn | FOOD chefs, Restaurants, Stores: They Want You To eat Well MACCABIAH Ten Oregonians Bound for Jewish Olympics in Israel ENERGY Renewables Are Big in Green Northwest Northwest Investment Counselors Team 15 years of Independent Advice and Integrity You’ve always known this day would come. We value transparency, prudence and creating Whether your wealth was part of an employer tailored portfolios for our clients, freeing them savings plan, locked up in a family trust, part from the worry about their fi nancial future. We of a loved one’s will or simply someone else’s align with our clients’ interests, charging solely responsibility, the worry of managing those a fee for management services, never any sales investments wasn’t yours. Now it is. commissions, account set-up fees or research fees. At NWIC, we are experts in helping clients with If that day has come, let us help shoulder the the sudden burden of responsibility for wealth. burden with you. 340 Oswego Pointe Drive, Suite 100 • Lake Oswego, Oregon, 97034 Offi ce: (503) 607-0032 • Toll-free (800) 685-7884 [email protected] • www.nwic.net Northwest Investment Counselors Team TRUSTWORTHY 15 years of Independent Advice and Integrity COMPREHENSIVE SOLUTIONS You’re Invited July 10th, 2013 FEDERAL INCOME TAXES, THEN AND NOW How the new tax laws might affect you. visit our website or call to register for this complimentary event GRETCHEN STANGIER, CFP® WWW.STANGIERWEALTHMANAGEMENT.COM 9955 SE WASHINGTON, SUITE 101 • PORTLAND, OR 97216 • 877-257-0057 • [email protected] SECURITIES AND ADVISORY SERVICES OFFERED THROUGH LPL FINANCIAL. -

Religion, Ethnicity and Contested Nationhood in the Former Ottoman Space Religion, Ethnicity and Contested Nationhood in the Former Ottoman Space

Religion, Ethnicity and Contested Nationhood in the Former Ottoman Space Religion, Ethnicity and Contested Nationhood in the Former Ottoman Space Edited by Jørgen Nielsen LEIDEN • BOSTON 2012 Cover photo taken from Gül McMillan and John Andrew McMillan, eds., Karaman Albümü. Kültür ve Tarih Kenti/City of Culture & History, Konya: McM Medya İletişim ve Tic. Ltd., 2001, p. 4. Th is book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Religion, ethnicity and contested nationhood in the former Ottoman space / edited by Jorgen Nielsen. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-90-04-21133-9 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Turkey--History--Mehmed VI, 1918-1922. 2. Balkan Peninsula--History--1918-1945. 3. Middle East--History--20th century. I. Nielsen, Jørgen S. DR589.R45 2012 956’.03--dc23 2011036719 ISBN 9789004211339 Copyright 2012 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, Th e Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to Th e Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. CONTENTS Contributors ...............................................................................................vii Introduction: New Perspectives on Ottoman History ............................1 Jørgen S. Nielsen PART ONE PERSPECTIVES ON OTTOMAN HISTORY 1. -

OWLS Honors Judge Tennyson, Elisa Dozono by Adele Ridenour N March 8, Over 550 Judge Katherine E

TM Published Quarterly by Oregon Women Lawyers Volume 30, No. 2 SPRING 2019 OWLS Honors Judge Tennyson, Elisa Dozono By Adele Ridenour n March 8, over 550 Judge Katherine E. Tennyson guests, including Gover- has served on the Multnomah Onor Kate Brown and At- County Circuit Court since 2002 torney General Ellen Rosenblum, and is currently its acting chief gathered at the Portland Art probate judge. Judge Tennyson Museum to honor Elisa Dozono, began her career as an attorney In This Issue a partner at Miller Nash Graham in the 1980s. She is a former & Dunn, and Judge Katherine board member of OWLS and the Roberts & Deiz Award Dinner Tennyson, of the Multnomah founder of the OWLS Judicial Time’s Up Program on May 8 County Circuit Court, with the Work Group, which helps recruit Past President’s Message 2019 OWLS Roberts and prepare attor- & Deiz Award.1 neys from outside Upcoming OWLS Events Elisa Dozono is a the dominant culture 30th Anniversary Celebration native Oregonian to apply for state Workplace Leader Nominations and a 2006 graduate and federal judicial of Lewis & Clark Law positions. She is also Capitol Update School. At Miller the founder of the Judge Rebecca Guptill Nash, Elisa special- OWLS First Gener- Fall CLE on Pay Equity izes in litigation ation Professionals and governmental Discussion Group, Thank You, Dinner Sponsors affairs work. She is an informal monthly When OWLS Was Formed also a volunteer pro Top: Elisa Dozono, Governor Kate Brown luncheon gathering Judges’ Forum tem judge on the Above: Governor Brown, Judge Katherine Tennyson, of attorneys who are and her spouse, Katie Meyer Meet Judge Debra Velure Washington County the first in their fam- Circuit Court. -

Oregon Benchmarks Spring 2001

Ore on BE CH THE U.S. DISTRICT COURT OF OREGON HISTORICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER Famous Federal Cases Series The Japanese Exclusion Case of United States v. Yasui By JOHN W. STEPHENS inoruYasui-born and raised in Hood River and elected citizenship of Japan by reason of his employ- Meducated at the University of Oregon-was just ment with the Consulate General of Japan in Chicago another American, or so he thought. But in March 1942 until December 8, 1941 (the first Monday immedi- Yasui's loyalty, and that of other Americans of Japa- ately following the attack on Pearl Harbor). Judge Fee nese descent, was called into question during the anti- sentenced Yasui to one year's imprisonment and a Japanese hysteria that followed the December 7, 1941 $5,000 fine. bombing of Pearl Harbor. The case was certified directly to the United States Yasui's case, United States v. Yasui, is the subject of Supreme Court, and on June 21, 1943-the same day the next program in the United States District Court of the Court in Hirabayashi v. United States upheld the Oregon Historical Society's "Famous Federal Cases" constitutionality of the curfew order as applied-that series. The panel presentation will be Thursday, May body also sustained the conviction of Yasui. The Court 24,2001 at 4:00 p.m. on the 16th floor of the Mark O. reversed Judge Fee's finding that Yasui had renounced Hatfield United States Courthouse, 1000 S.W Third his U.S. citizenship, but it upheld the constitutionality Avenuein Portland. The presentation will last 90 min- of the curfew order in light of its decision in utes, with time for questions and discussion following. -

Decolonizing Methodologies: Traditional and Digital Archives

the propensity of the academy to view historical purveyors of intellectual thought as overwhelmingly European, and the invisibility of subaltern agents in Decolonizing Methodologies: traditional and digital archives. Sites of subaltern experience drift in and out of the historical record Recovery and Access Amidst often leaving no tangible signifiers to how these events the Ruins inform the racialized, gendered, and class based systems of power which influenced many of the Christy Hyman negotiations that subaltern agents contended with in [email protected] initiating action and decision-making in an oppressive University of Nebraska-Lincoln world. Historical recovery in the digital humanities United States of America play a vital role in enabling users with access to new knowledge as well as helping to shape meaning and Anelise Shrout interpretation of the cataclysmic phenomena [email protected] embedded within its mediums. Anelise Shrout’s call California State University-Fullerton, United States of for history from below is essential to creating digital America content which enables accessibility and users potentiality of increased awareness of the historical Kathryn Kaczmarek-Frew underpinnings related to structural inequality- Shrout [email protected] rightly declares that digital methodologies are ideally University of Maryland, United States of America suited for these interventions (Shrout 2016). This panel offers several approaches to historical Hilary Green recovery through showcasing digital projects which [email protected] utilize technologies designed to foreground subaltern University of Alabama, United States of America histories while preserving contextual integrity. We bring together three approaches- geospatial, alternate Nishani Frazier reality gaming, and online digital collections for a [email protected] conversation that will highlight the methods and Miami University, United States of America values involved in the digitization, visualization, user interaction and theoretical analysis of content. -

House Concurrent Resolution 213 Sponsored by COMMITTEE on RULES (At the Request of Representative Jennifer Williamson)

79th OREGON LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY--2018 Regular Session Enrolled House Concurrent Resolution 213 Sponsored by COMMITTEE ON RULES (at the request of Representative Jennifer Williamson) Whereas Vera Katz was born on August 3, 1933, in Dusseldorf, Germany, to Lazar and Raissa Pistrak; and Whereas the Pistrak family left Germany for France when Vera was just two months old, and in 1940 they fled invading German armies for Spain on foot over the Pyrenees Mountains, a journey that ultimately led them to New York City; and Whereas Vera Katz attended Brooklyn College, where she studied dance under the legendary Martha Graham and received a degree in sociology; and Whereas Vera Katz and her husband, Mel Katz, moved to Portland, Oregon, in the early 1960s, where they raised their young son, Jesse; and Whereas Vera Katz first became involved in politics as a volunteer in Robert F. Kennedy’s 1968 presidential campaign; and Whereas Vera Katz was elected in 1972 to the Oregon House of Representatives, where she represented the people of her Multnomah County district for two decades; and Whereas Vera Katz joined with two other legendary Oregon politicians, Norma Paulus and Betty Roberts, to form the Legislative Assembly’s first-ever Women’s Caucus; and Whereas in 1977, Vera Katz became the first woman in Oregon history to serve as chair of the Ways and Means Committee; and Whereas Vera Katz was Speaker of the House of Representatives from 1985 to 1990, becoming Oregon’s first female Speaker and just the second woman nationwide to serve in that capacity; -

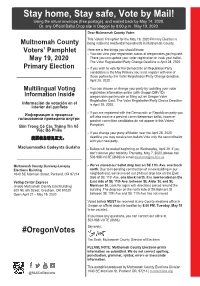

Stay Home, Stay Safe, Vote by Mail! Using the Return Envelope (Free Postage), and Mailed Back by May 14, 2020

Stay home, Stay safe, Vote by Mail! Using the return envelope (free postage), and mailed back by May 14, 2020. Or, any Official Ballot Drop site in Oregon by 8:00 p.m., May 19, 2020. Dear Multnomah County Voter: This Voters’ Pamphlet for the May 19, 2020 Primary Election is Multnomah County being mailed to residential households in Multnomah County. Here are a few things you should know: Voters’ Pamphlet • You can view your registration status at oregonvotes.gov/myvote. There you can update your voter registration or track your ballot. May 19, 2020 The Voter Registration/Party Change Deadline is April 28, 2020. Primary Election • If you wish to vote for the Democratic or Republican Party candidates in the May Primary you must register with one of __________________ those parties by the Voter Registration/Party Change deadline, April 28, 2020. Multilingual Voting • You can choose or change your party by updating your voter registration information online (with Oregon DMV ID) Information Inside oregonvotes.gov/myvote or filling out an Oregon Voter Registration Card. The Voter Registration/Party Choice Deadline Información de votación en el is April 28, 2020. interior del panfleto • If you are registered with the Democratic or Republican party you Информация о процессе will also receive a precinct committeeperson ballot, however голосовании приведена внутри precinct committee candidates do not appear in this Voters’ Bên Trong Có Các Thông Tin Về Pamphlet. Việc Bỏ Phiếu • If you change your party affiliation near the April 28, 2020 投票信息请见正文。 deadline you may receive two ballots Vote only the second ballot with your new party.