She Flies with Her Own Wings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Jennifer E. Manning Information Research Specialist Colleen J. Shogan Deputy Director and Senior Specialist November 26, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30261 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Summary Ninety-four women currently serve in the 112th Congress: 77 in the House (53 Democrats and 24 Republicans) and 17 in the Senate (12 Democrats and 5 Republicans). Ninety-two women were initially sworn in to the 112th Congress, two women Democratic House Members have since resigned, and four others have been elected. This number (94) is lower than the record number of 95 women who were initially elected to the 111th Congress. The first woman elected to Congress was Representative Jeannette Rankin (R-MT, 1917-1919, 1941-1943). The first woman to serve in the Senate was Rebecca Latimer Felton (D-GA). She was appointed in 1922 and served for only one day. A total of 278 women have served in Congress, 178 Democrats and 100 Republicans. Of these women, 239 (153 Democrats, 86 Republicans) have served only in the House of Representatives; 31 (19 Democrats, 12 Republicans) have served only in the Senate; and 8 (6 Democrats, 2 Republicans) have served in both houses. These figures include one non-voting Delegate each from Guam, Hawaii, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Currently serving Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-MD) holds the record for length of service by a woman in Congress with 35 years (10 of which were spent in the House). -

50 Years of Oregon Senior and Disability Policy and Advocacy: an Historical Chronology 1969-2019

50 Years of Oregon Senior and Disability Policy and Advocacy: An Historical Chronology 1969-2019 By Dr. James (Jim) Davis Oregon State Council for Retired Citizens United Seniors of Oregon December 2020 0 Table of Contents Introduction Page 3 Yearly Chronology of Senior and Disability Policy and Advocacy 5 1969 5 1970 5 1971 6 1972 7 1973 8 1974 10 1975 11 1976 12 1977 13 1978 15 1979 17 1980 19 1981 22 1982 26 1983 28 1984 30 1985 32 1986 35 1987 36 1988 38 1989 41 1990 45 1991 47 1992 50 1993 53 1994 54 1995 55 1996 58 1997 60 1998 62 1999 65 2000 67 2001 68 2002 75 2003 76 2004 79 2005 80 2006 84 2007 85 2008 89 1 2009 91 2010 93 2011 95 2012 98 2013 99 2014 102 2015 105 2016 107 2017 109 2018 114 2019 118 Conclusion 124 2 50 Years of Oregon Senior and Disability Policy and Advocacy: An Historical Chronology 1969-2019 Introduction It is my pleasure to release the second edition of the 50 Years of Oregon Senior and Disability Policy and Advocacy: An Historical Chronology 1969-2019, a labor of love project that chronicles year-by-year the major highlights and activities in Oregon’s senior and disability policy development and advocacy since 1969, from an advocacy perspective. In particular, it highlights the development and maintenance of our nationally-renown community-based long term services and supports system, as well as the very strong grassroots, coalition-based advocacy efforts in the senior and disability communities in Oregon. -

Download the Report

Oregon Cultural Trust fy2011 annual report fy2011 annual report 1 Contents Oregon Cultural Trust fy2011 annual report 4 Funds: fy2011 permanent fund, revenue and expenditures Cover photos, 6–7 A network of cultural coalitions fosters cultural participation clockwise from top left: Dancer Jonathan Krebs of BodyVox Dance; Vital collaborators – five statewide cultural agencies artist Scott Wayne 8–9 Indiana’s Horse Project on the streets of Portland; the Museum of 10–16 Cultural Development Grants Contemporary Craft, Portland; the historic Astoria Column. Oregonians drive culture Photographs by 19 Tatiana Wills. 20–39 Over 11,000 individuals contributed to the Trust in fy2011 oregon cultural trust board of directors Norm Smith, Chair, Roseburg Lyn Hennion, Vice Chair, Jacksonville Walter Frankel, Secretary/Treasurer, Corvallis Pamela Hulse Andrews, Bend Kathy Deggendorfer, Sisters Nick Fish, Portland Jon Kruse, Portland Heidi McBride, Portland Bob Speltz, Portland John Tess, Portland Lee Weinstein, The Dalles Rep. Margaret Doherty, House District 35, Tigard Senator Jackie Dingfelder, Senate District 23, Portland special advisors Howard Lavine, Portland Charlie Walker, Neskowin Virginia Willard, Portland 2 oregon cultural trust December 2011 To the supporters and partners of the Oregon Cultural Trust: Culture continues to make a difference in Oregon – activating communities, simulating the economy and inspiring us. The Cultural Trust is an important statewide partner to Oregon’s cultural groups, artists and scholars, and cultural coalitions in every county of our vast state. We are pleased to share a summary of our Fiscal Year 2011 (July 1, 2010 – June 30, 2011) activity – full of accomplishment. The Cultural Trust’s work is possible only with your support and we are pleased to report on your investments in Oregon culture. -

OWLS Honors Judge Darleen Ortega and Secretary of State Kate Brown

Published Quarterly by Oregon Women Lawyers Volume 22, No. 2 Spring 2011 22 years of breaking barriers OWLS Honors Judge Darleen Ortega 1989 -2011 and Secretary of State Kate Brown By Rose Alappat and the 2010 recipient of the Justice Betty Rob- President erts Award. The second auction item, a trip to Concetta Schwesinger Ashland, went to Julia Markley, also a partner Vice President, at Perkins Coie. President-Elect Heather L. Weigler During dessert, OWLS President Concetta Secretary Schwesinger thanked the dinner sponsors, in- Cashauna Hill cluding title sponsor Miller Nash, and recognized Treasurer the distinguished judges, political leaders, and Megan Livermore guests in attendance. A thoughtful slide show Historian presented views on women in the legal profession Kathleen J. Hansa Rastetter and highlighted the accomplishments of Justice Board Members Betty Roberts and Judge Mercedes Deiz. Sally Anderson-Hansell The Justice Betty Roberts Award was then Hon. Frances Burge Photo by Jodee Jackson Megan Burgess presented to Oregon Secretary of State Kate Bonnie Cafferky Carter Judge Darleen Ortega (left) and Alec Esquivel Brown. The award recognizes an individual Dana Forman Gina Hagedorn our hundred fifty people gathered on Heather Hepburn March 11 at the Governor Hotel in Port- Kendra Matthews land to celebrate the OWLS community Linda Meng F Elizabeth Tedesco Milesnick and honor two people who have supported Hon. Julia Philbrook and inspired women and minorities in the legal Cassandra SkinnerLopata Hon. Katherine Tennyson profession. The Roberts-Deiz Awards Dinner Shannon Terry sold out especially quickly this year, perhaps in Heather Walloch recognition of the influence and achievements Hon. -

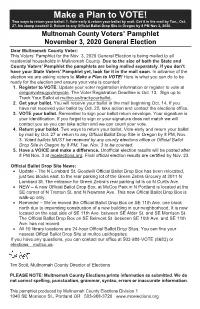

Make a Plan to VOTE! Two Ways to Return Your Ballot: 1

Make a Plan to VOTE! Two ways to return your ballot: 1. Vote early & return your ballot by mail. Get it in the mail by Tue., Oct. 27. No stamp needed! 2. Return to any Official Ballot Drop Site in Oregon by 8 PM Nov 3, 2020. Multnomah County Voters’ Pamphlet November 3, 2020 General Election Dear Multnomah County Voter: This Voters’ Pamphlet for the Nov. 3, 2020 General Election is being mailed to all residential households in Multnomah County. Due to the size of both the State and County Voters’ Pamphlet the pamphlets are being mailed separately. If you don’t have your State Voters’ Pamphlet yet, look for it in the mail soon. In advance of the election we are asking voters to Make a Plan to VOTE! Here is what you can do to be ready for the election and ensure your vote is counted: 1. Register to VOTE. Update your voter registration information or register to vote at oregonvotes.gov/myvote. The Voter Registration Deadline is Oct. 13. Sign up to Track Your Ballot at multco.us/trackyourballot. 2. Get your ballot. You will receive your ballot in the mail beginning Oct. 14. If you have not received your ballot by Oct. 22, take action and contact the elections office. 3. VOTE your ballot. Remember to sign your ballot return envelope. Your signature is your identification. If you forget to sign or your signature does not match we will contact you so you can take action and we can count your vote. 4. Return your ballot. -

*Vaten&' 'Pamftatet

3 . OS 27 £ ) r 3 1 ) Q ( d & I # STATE OF OREGON »_ / 3 ’'* L. *£• v / * '■* iOUJEGTlOII *Vaten&’ ’Pam ftA tet General Election November 6, 1962 Compiled and Distributed by HOWELL APPLING, Jr. Secretary of State Marion County INFORMATION FOR VOTERS (1) Requirements for a citizen to of election year). Applicatio qualify as a voter: includes: Citizen of the United States. Your signature. Twenty-one or more years of age. Address or precinct number. Resided in the state at least six Statement of reason for ap months. plication. Able to read and write English. Applications filed less than five Registered as an elector with the days before election, Novem County Clerk or official regis ber 1-5, require a d d ition a l trar at least 30 days before statement that: election. Voter is physically unable to get to the polls, or (2) Voting by absentee ballot. Voter was unexpectedly You may apply for an absentee called out of county in the ballot if: five-day period. You are a registered voter. Emergencies on Election Day: (“Service voters” are auto Physical d is a b ility must be matically registered by fol certified by licensed practi lowing the service voting procedure.) tioner of healing arts or au thorized C h ristian Science You have reason to believe practitioner. In v olu n ta ry you will be absent from public services such as fire your cou n ty on election fighting to be certified by day. person in charge. You live more than 15 miles Ballot, when voted by elector, from your polling place. -

City of Portland

CITY OF PORTLAND Mayor Mayor CHARLIE JEFFERSON HALES SMITH OCCUPATION: Senior Vice OCCUPATION: State President, HDR Engineering Representative, East Portland OCCUPATIONAL OCCUPATIONAL BACKGROUND: Small BACKGROUND: Founding Business Owner, Friends Executive Director, Oregon of Trees, Portland Parks Bus Project; Community Foundation, Hayhurst Organizer; Clerk, U.S. Court of Neighborhood Association Appeals EDUCATIONAL EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND: Lewis and BACKGROUND: Grant HS, Clark College; University of University of Oregon, Harvard Virginia Law School PRIOR GOVERNMENTAL EXPERIENCE: Portland City PRIOR GOVERNMENTAL EXPERIENCE: Oregon House Commissioner of Representatives; House Democratic Leadership; Oregon Transparency Commission The Progressive Mayor We Can Count On “The 2011 Small Business Champion” “Charlie doesn’t just have Portland’s values — he makes them Oregon Microenterprise Network work. He’s the one who will really move Portland forward.” — Former Mayor Vera Katz Dear Neighbor, “The city needs a mayor who can work with others and get I‘m running for mayor to get Portland working better for everyone. things done. Charlie has the character and good judgment to make the right decisions for Portland.” – My priorities were shaped growing up in Portland, building Governor Ted a successful organization, and serving Portlanders in tough Kulongoski times: “He’ll deliver community policing, improve police accountability Homegrown Jobs: As Mayor, I’ll help local businesses and get illegal guns off our streets.” – Rosie Sizer, Former grow and thrive, boost workforce training, and spur smart Police Chief infrastructure, sustainable building retrofits and balanced transportation. “Charlie’s the proven choice for schools: he protected school days and teaching positions across Portland. As Mayor he’ll Safe & Healthy Families: I’ve worked to preserve vital get more resources into our classrooms.”– School Board services as budgets tightened, and led on MAX safety and Member Bobbie Regan curbing human trafficking. -

A Brief History of Civc Space in Portland Oregon Since World War II Including Origins of Café Soceity

A Brief History of Civc Space in Portland Oregon Since World War II Including Origins of Café Soceity In post World War II Portland, Portlanders were in love with their automobiles, while civic leaders and engineers planned freeways and expressways and vacant land in the central city was paved over for parking lots. Robert Moses came to Portland in 1943 and laid out a blueprint for the future of Portland, one hatch marked with freeways and thoroughfares slicing and dicing the city into areas separated by high speed cement rivers. Freeways completed during this period, such as Interstate 5, tore through minority and poor neighborhoods, such as Albina, with little collective resistance. It was a good time to be a road engineer, a poor time if you were African American. Portland was proud of its largest mall, Lloyd Center; for a short period of time the largest mall in the country. It was a sign of progress. Teenagers spent their time driving between drive-in restaurants and drive-in movies, or cruising downtown streets to be seen. Adults spent their time at home in front of that marvelous new invention, the television, or often in private clubs. Nearly a quarter of all civic associations were temples, lodges or clubs. During this period, civic leaders in Portland took pride in early urban renewal projects such as the South Auditorium project that required the demolition of 382 buildings and the relocation of 1,573 residents and 232 businesses. The project effectively terminated one of Portland's Jewish and Eastern European enclaves, and dispersed a sizable gypsy population to the outer reaches of southeast Portland. -

How the Breathers Beat the Burners: the Policy Market and The

HOW THE BREATHERS BEAT THE BURNERS: THE POLICY MARKET AND THE ROLE OF TECHNICAL, POLITICAL, AND LEGAL CAPITAL IN PURSUING POLICY OUTCOMES. By AARON J. LEY A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of Political Science MAY 2011 To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the dissertation of AARON J. LEY find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ______________________________ J. Mitchell Pickerill, Ph.D., Co-Chair ______________________________ Cornell W. Clayton, Ph.D., Co-Chair ______________________________ Edward P. Weber, Ph.D. ii Acknowledgements This dissertation was written over a period of three years and the final product would not have been possible if not for the invaluable support from family, friends, mentors, institutions, and colleagues. My dissertation committee deserves first mention. They truly have molded me into the man I am today. Cornell Clayton, Mitch Pickerill, and Ed Weber have not only made me a better scholar, but they‘ve taught me important things about life. My family deserves recognition for the support and encouragement I have received throughout the years. Mom and Dad, when the going got tough I thought about how proud you both would be after I finished this project – these dreams are your‘s and mine that time can‘t take away. Todd and Allison, thanks for giving me a place to focus my eyes on the catalyst and stand high in the middle of South Minneapolis. Wade Ley deserves special mention for his qualitative research assistance about the Pacific Northwest hop industry in Seattle, Portland, and Spokane during Spring 2010. -

The Urban League of Poruand

BOARD OF DRECTGRS APRL 15, 1937 12:00IPIiIrI NOON[eIIi MULT-PJRPOSEMULTI-PURPOSE CONFERENCECONFERENCE ROOMROOM JEAN PLAZA The UrbanUrban LeagueLeague ofof PortDandPorUand URBAN PLAZA 10 North Russell Street Portland, Oregon 97227 (503) 280-2600 AGENDA APPROVAL OF MINUTES COMMITTEE REPORTS 1. Finance 2. Fund Raising 3. Program and Planning 4. Personnel 5. Nominating REPORT OF THE PRESIDENT AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER REPORT OF THE CHAIRPERSON ITEMS OFDF INFORMATIONINFORMATION 1. Report of the President 2. Financial Report 3. Letter from Don Frisbee and Herb'sresponse 4. EOD Congratulatory Letters 5. Letter to Larry Frager 6. Proposal toto thethe JuvenileJuvenile ServicesServices ComniissionCommission 7. Testimony to State Legislatureon South Africa 8. Letter from Natale SicuroSicuro andand Herb'sHerb'sresponse 9-9. Letter to Natale Sicuro 10. Whitney M. Young Learning Center Flyer 11. Employment Placement List 12. ESI Stock Certificate 13. Letter from Walter Morris and Herb's response 14. Los Angeles UrbanUrban LeagueLeague ProgramnieProgramme Book URBAN LEAGUE OF PORTLAND BOARD OF DIRECTORS MARCH 18, 1987 The March meeting of the Urban League Board of Directors, held in the Multi-Purpose Conference Room, Urban Plaza, 10 North Russell Street, was called to order at 12:18 P.M. by Chairperson Linda Rasmussen. The following Directors were in attendance: Donny Adair, Bobbie Gary, Avel Gordly, Tom Kelley, Shirley Minor, Linda Rasmussen, Joel Smith, Irwin Starr, Bob Sutcliff, Peter Thompson, Thane Tienson, Jack Vogel and Valerie White. The following Directors were absent with excuse: Bridget Flanagan, Jeff Millner, Larry Raff and Nancy Wilgenbusch. The following Director was absent without excuse: Skip Collier. Staff in attendance were: Herb Cawthorne, Carol Sutcliff, Ray Leary and Pauline Reed. -

Senate Majority Office

SENATE MAJORITY OFFICE Oregon State Legislature State Capitol Salem, OR NEWS RELEASE April 9, 2019 CONTACT: Rick Osborn, 503-986-1074 [email protected] National Popular Vote bill clears Oregon State Senate SB 870: Compact would ensure one person, one vote in presidential elections SALEM – The Oregon Senate moved forward with legislation that will take the United States toward a national popular vote for presidential elections. Senate Bill 870 – which passed with a bipartisan vote on the Senate floor today – makes Oregon part of the National Popular Vote Compact, an agreement between states where they will award their Electoral College votes to the presidential candidate who receives the most votes nationally. The authority to appoint electors is granted to each state “in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct,” according to the United States Constitution. “One of things I’m most proud of is how over the history of this country we’ve expanded the franchise and given voters more of a direct say in the election of our leaders,” Sen. Michael Dembrow (D-Portland), who co-carried the bill with Sen. Brian Boquist (R-Dallas) on the Senate floor. “Over time we’ve decided that it’s really important to have people have a direct say in the outcome of elections. We now have 14 other states and the District of Columbia in the compact, and it’s being considered in a number of different states. It’s way past time for Oregon to join them.” The United States Constitution establishes the Electoral College as the mechanism for choosing the President of the United States. -

1993 Fall Advancesheet

A newsletter published by Oregon Women Lawyers Volume 4, No.4 Fall1993 L::::s OREGON WOMEN 1LAWYJER§~ llllll Who He Are & Where He're Going ,~ OREGO,Nwomen By Mary Beth Allen lAW Y E R s'" hile the official genesis of Oregon them for breakfast and a discussion about form W Women Lawyers might be open to ing a statewide women's bar organization. Fol President Diana Craine debate, four of the group's founders agree on lowing that meeting, at which The Hon. Betty thesiteofits unofficial origins: KatherineO'Neil's Roberts and The Hon. Mercedes Deiz spoke, a President Elect/ Vice President living room. brainstorming Helie Rode " It was like a session was held Secretary salon," says in November at Susana A lba Nell Hoffman the state bar Treasurer Bonaparte of headquarters. Phylis Myles the experience The women de Historian Tru dy A llen ofmeetingwith cided that day to other women at form their own Board Members Colette Boehmer 0' eiJ's_hous_e..._ bar asso.ciation julie Levie Caron to discuss form to forward their jeanean West Craig ing Oregon' s goal of advanc Michele Longo Eder Susa n Eggum first statewid~ ing women and Susa n Evans Grabe women's bar minorities in the jennifer Harrington association. "A legal profession. Susa n Isaacs political, social, Oregon Kay Kinsley Trudy Allen (OWLS and Queen's Bench board member), janet Lee Knottnerus educational sa Women Lawyers Andrea Swanner Redding Regnell (Mary Leonard Society president), Kathryn Ricciardelli Kathryn Ri cciardelli lon. It was excit (outgoing OWLS president), Nancy Moriarty (Queen's Bench held its first Noreen Saltveit ingtobeinvolved president) and Loree Devery (Queen's Bench treasurer) proudly conference on Cristina Sanz with so many dy April1, 1989 in Shelley Smith show off their OWLS' shirts and mugs.