Myanmar's Cross-Border Economic Relations and Cooperation with The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fund for HIV/AIDS in Myanmar UNAIDS

Annual Progress Report, 1 Apr 2006 - 31 Mar 2007 Table of Contents Foreword 3 About this report 5 Highlights in Achievements 7 Progress and Achievements 9 ....... Access to services to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV improved 9 ....... Access to services to prevent transmission of HIV in injecting drug use ....... improved 18 ....... Knowledge and attitudes improved 27 ....... Access to services for HIV care and support improved 30 Fund Management 41 ....... Programmatic and Financial Monitoring 41 ....... Financial Status and Utilisation of Funds 43 Operating Environment 44 Annexe 1: Implementing Partners expenditure and budgets 45 Annexe 2: Summary of Technical Progress Apr 2004–Mar 2007 49 Annexe 3: Achievements by Implementing Partners Round II, II(b) 50 Annexe 4: Guiding principles for the provision of humanitarian assistance 57 Acronyms and abbreviations 58 1 Fund for HIV/AIDS in Myanmar UNAIDS 2 Annual Progress Report, 1 Apr 2006 - 31 Mar 2007 Foreword This report will be the last for the Fund for HIV/AIDS in Myanmar (FHAM), covering its fourth and final year of operation (the fiscal year from April 2006 through March 2007). Created as a pooled funding mechanism in 2003 to support the United Nations Joint Programme on AIDS in Myanmar, the FHAM has demonstrated that international resources can be used to finance HIV services for people in need in an accountable and transparent manner. As this report details, progress has been made in nearly every area of HIV prevention – especially among the most at-risk groups related to sex work and drug use – and in terms of care and support, including anti-retroviral treatment. -

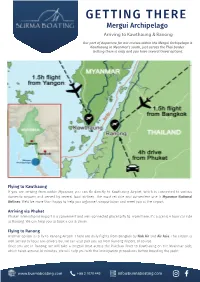

GETTING THERE Mergui Archipelago Arriving to Kawthaung & Ranong

GETTING THERE Mergui Archipelago Arriving to Kawthaung & Ranong Our port of departure for our cruises within the Mergui Archipelago is Kawthaung in Myanmar’s south, just across the Thai border. Getting there is easy and you have several travel options. Flying to Kawthaung If you are arriving from within Myanmar, you can fly directly to Kawthaung Airport, which is connected to various domestic airports and served by several local airlines. The most reliable and convenient one is Myanmar National Airlines. We’d be more than happy to help you organise transportation and meet you at the airport. Arriving via Phuket Phuket International Airport is a convenient and well-connected place to fly to. From there, it’s a scenic 4 hour car ride to Ranong. We can help you to book a car & driver. Flying to Ranong Another option is to fly to Ranong Airport. There are daily flights from Bangkok by Nok Air and Air Asia. The airport is well served by local taxi drivers but we can also pick you up from Ranong Airport, of course. Once you are in Ranong, we will take a longtail boat across the Pakchan River to Kawthaung on the Myanmar side, which takes around 30 minutes. We will help you with the immigration procedures before boarding the yacht. www.burmaboating.com +66 2 1070 445 [email protected] GETTING THERE Mergui Archipelago Crossing the Thai-Myanmar border In the case you arrive through the Thailand side and doesn’t want our assistance, here is a quick step by step instruction to cross the border between the 2 countries. -

Myanmar Receives 30,000 Remdesivir Drugs Used in COVID-19 Treatment from NSIC

DON’T BE TOO FEARFUL BUT TAKE CARE OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC PAGE-8 (OPINION) NATIONAL NATIONAL MoC facilitates import of COVID-19 MoHS Union Minister discusses COVID-19-related devices to be delivered without delay on matters with Yangon Region Administration public holidays Council members, regions/states health officials PAGE-3 PAGE-4 Vol. VIII, No. 93, 13th Waxing of Waso 1383 ME www.gnlm.com.mm Wednesday, 21 July 2021 Five-Point Road Map of the State Administration Council 1. The Union Election Commission will be reconstituted and its mandated tasks, including the scrutiny of voter lists, shall be implemented in accordance with the law. 2. Effective measures will be taken with added momentum to prevent and manage the COVID-19 pandemic. 3. Actions will be taken to ensure the speedy recovery of businesses from the impact of COVID-19. 4. Emphasis will be placed on achieving enduring peace for the entire nation in line with the agreements set out in the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement. 5. Upon accomplishing the provisions of the state of emergency, free and fair multiparty democratic elections will be held in line with the 2008 Constitution, and further work will be undertaken to hand over State duties to the winning party in accordance with democratic standards. Myanmar receives 30,000 Remdesivir drugs used in COVID-19 treatment from NSIC A TATMADAW aircraft landed at Nay Pyi Taw Airport, carry- ing 30,000 Remdesivir drugs donated by the National Stra- tegic Investment Corporation Co. Ltd (NSIC) to the State Administration Council from Hyderabad, India, yesterday evening. -

Covid-19 Response Situation Report 3 | 1 May 2020

IOM MYANMAR COVID-19 RESPONSE SITUATION REPORT 3 | 1 MAY 2020 2,500 migrant per day to be allowed to return through the Myawaddy-Mae Sot border gate 16,324 migrants registered online in preparation to return through the Myawaddy-Mae Sot border gate 3,125 international migrants returned to Kachin State mainly from the People’s Republic of China Migrants preparing to return to their communities of origin following 21 days of quarantine at Myawaddy, Kayin State. © IOM 2020 SITUATION OVERVIEW The border with Thailand was expected to re-open on 1 May of China and through the Lweje border gate, according to data to allow a second large influx of migrants (estimated 20,000 from the Kachin State Government (695 internal migrants also to 50,000 returns). The Myanmar Government requested to returned from other states and regions of Myanmar). the Thai Government to only allow 2,500 returnees per day Returnees are being transported to Myitkyina, and from there, through the Myawaddy border gate; however, due to the to their communities of origin where they will stay in extension of the Emergency Decree in Thailand until 31 May, community-based facility quarantine centres. returns are delayed for a few more days to allow for the necessary arrangements to be put in place by Thai authorities. Government Ministries and Departments, the State Government, UN agencies and other actors supporting the COVID-19 response are closely observing the situation in order to quickly respond to potential large scale returns in the coming days. It is expected that approximately 2,000 returning migrants will be quarantined in Myawaddy, while the remainder will be transported from the border to their home communities for community-based quarantine. -

Shan State - Myanmar

Myanmar Information Management Unit SHAN STATE - MYANMAR Mohnyin 96°40'E Sinbo 97°30'E 98°20'E 99°10'E 100°0'E 100°50'E 24°45'N 24°45'N Bhutan Dawthponeyan India China Bangladesh Myo Hla Banmauk KACHIN Vietnam Bamaw Laos Airport Bhamo Momauk Indaw Shwegu Lwegel Katha Mansi Thailand Maw Monekoe Hteik Pang Hseng (Kyu Koke) Konkyan Cambodia 24°0'N Muse 24°0'N Muse Manhlyoe (Manhero) Konkyan Namhkan Tigyaing Namhkan Kutkai Laukkaing Laukkaing Mabein Tarmoenye Takaung Kutkai Chinshwehaw CHINA Mabein Kunlong Namtit Hopang Manton Kunlong Hseni Manton Hseni Hopang Pan Lon 23°15'N 23°15'N Mongmit Namtu Lashio Namtu Mongmit Pangwaun Namhsan Lashio Airport Namhsan Mongmao Mongmao Lashio Thabeikkyin Mogoke Pangwaun Monglon Mongngawt Tangyan Man Kan Kyaukme Namphan Hsipaw Singu Kyaukme Narphan Mongyai Tangyan 22°30'N 22°30'N Mongyai Pangsang Wetlet Nawnghkio Wein Nawnghkio Madaya Hsipaw Pangsang Mongpauk Mandalay CityPyinoolwin Matman Mandalay Anisakan Mongyang Chanmyathazi Ai Airport Kyethi Monghsu Sagaing Kyethi Matman Mongyang Myitnge Tada-U SHAN Monghsu Mongkhet 21°45'N MANDALAY Mongkaing Mongsan 21°45'N Sintgaing Mongkhet Mongla (Hmonesan) Mandalay Mongnawng Intaw international A Kyaukse Mongkaung Mongla Lawksawk Myittha Mongyawng Mongping Tontar Mongyu Kar Li Kunhing Kengtung Laihka Ywangan Lawksawk Kentung Laihka Kunhing Airport Mongyawng Ywangan Mongping Wundwin Kho Lam Pindaya Hopong Pinlon 21°0'N Pindaya 21°0'N Loilen Monghpyak Loilen Nansang Meiktila Taunggyi Monghpyak Thazi Kenglat Nansang Nansang Airport Heho Taunggyi Airport Ayetharyar -

(BRI) in Myanmar

MYANMAR POLICY BRIEFING | 22 | November 2019 Selling the Silk Road Spirit: China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Myanmar Key points • Rather than a ‘grand strategy’ the BRI is a broad and loosely governed framework of activities seeking to address a crisis in Chinese capitalism. Almost any activity, implemented by any actor in any place can be included under the BRI framework and branded as a ‘BRI project’. This allows Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and provincial governments to promote their own projects in pursuit of profit and economic growth. Where necessary, the central Chinese government plays a strong politically support- ive role. It also maintains a semblance of control and leadership over the initiative as a whole. But with such a broad framework, and a multitude of actors involved, the Chinese government has struggled to effectively govern BRI activities. • The BRI is the latest initiative in three decades of efforts to promote Chinese trade and investment in Myanmar. Following the suspension of the Myitsone hydropower dam project and Myanmar’s political and economic transition to a new system of quasi-civilian government in the early 2010s, Chinese companies faced greater competition in bidding for projects and the Chinese Government became frustrated. The rift between the Myanmar government and the international community following the Rohingya crisis in Rakhine State provided the Chinese government with an opportunity to rebuild closer ties with their counterparts in Myanmar. The China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) was launched as the primary mechanism for BRI activities in Myanmar, as part of the Chinese government’s economic approach to addressing the conflicts in Myanmar. -

The Union Report the Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Census Report Volume 2

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report The Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Volume Report : Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Figure 1: Map of Myanmar by State, Region and District Census Report Volume 2 (Union) i Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014 and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is my hope that the main census results will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and Offices at all administrative levels and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. -

Military Brotherhood Between Thailand and Myanmar: from Ruling to Governing the Borderlands

1 Military Brotherhood between Thailand and Myanmar: From Ruling to Governing the Borderlands Naruemon Thabchumphon, Carl Middleton, Zaw Aung, Surada Chundasutathanakul, and Fransiskus Adrian Tarmedi1, 2 Paper presented at the 4th Conference of the Asian Borderlands Research Network conference “Activated Borders: Re-openings, Ruptures and Relationships”, 8-10 December 2014 Southeast Asia Research Centre, City University of Hong Kong 1. Introduction Signaling a new phase of cooperation between Thailand and Myanmar, on 9 October 2014, Thailand’s new Prime Minister, General Prayuth Chan-o-cha took a two-day trip to Myanmar where he met with high-ranked officials in the capital Nay Pi Taw, including President Thein Sein. That this was Prime Minister Prayuth’s first overseas visit since becoming Prime Minister underscored the significance of Thailand’s relationship with Myanmar. During their meeting, Prime Minister Prayuth and President Thein Sein agreed to better regulate border areas and deepen their cooperation on border related issues, including on illicit drugs, formal and illegal migrant labor, including how to more efficiently regulate labor and make Myanmar migrant registration processes more efficient in Thailand, human trafficking, and plans to develop economic zones along border areas – for example, in Mae 3 Sot district of Tak province - to boost trade, investment and create jobs in the areas . With a stated goal of facilitating border trade, 3 pairs of adjacent provinces were named as “sister provinces” under Memorandums of Understanding between Myanmar and Thailand signed by the respective Provincial governors during the trip.4 Sharing more than 2000 kilometer of border, both leaders reportedly understood these issues as “partnership matters for security and development” (Bangkok Post, 2014). -

Transport Logistics

MYANMAR TRADE FACILITATION THROUGH LOGISTCS CONNECTIVITY HLA HLA YEE BITEC , BANGKOK 4.9.15 [email protected] Total land area 677,000sq km Total length (South to North) 2,100km (East to West) 925km Total land boundaries 5,867km China 2,185km Lao 235km Thailand 1,800km Bangladesh 193km India 1,463km Total length of coastline 2,228km Capital : Naypyitaw Language :Myanmar MYANMAR IN 2015 REFORM & FAST ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS SIGNIFICANT POTENTIAL CREDIBILITY AMONG ASEAN NATIONS GATE WAY “ CHINA & INDIA & ASEAN” MAXIMIZING MULTIMODALTRANSPORT LINKAGES EXPEND GMS ECONOMIC TRANSPORT CORRIDORS EFFECTIVE EXTENSION INTO MYANMAR INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTION TRADE AND LOTISGICS SUPPLY CHAIN TRANSPARENCY & PREDICTABILITY LEGAL & REGULATORY FREAMEWORK INFRASTUCTURE INFORMATION CORRUPTION FIANACIAL SERVICE “STRENGTHEING SME LOGISTICS” INDUSTRIAL ZONE DEVELOPMENT 7 NEW IZ KYAUk PHYU Yadanarbon(MDY) SEZ Tart Kon (NPD) Nan oon Pa han 18 Myawadi Three pagoda Existing IZ Pon nar island Yangon(4) Mandalay Meikthilar Myingyan Yenangyaing THI LA WAR Pakokku SEZ Monywa Pyay Pathein DAWEI Myangmya SEZ Hinthada Mawlamyaing Myeik Taunggyi Kalay INDUSTRIES CATEGORIES Competitive Industries Potential Industries Basic Industries Food and Beverages Automobile Parts Agricultural Machinery Garment & Textile Industrial Materials Agricultural Fertilizer Household Woodwork Minerals & Crude Oil Machinery & spare parts Gems & Jewelry Pharmaceutical Electrical & Electronics Construction Materials Paper & Publishing Renewable Energy Household products TRANSPORT -

Recent Arrests List

ƒ ARRESTS No. Name Sex Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD S: 8 of the Export and Superintendent Kyi 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Import Law Lin of Special Branch President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s S: 25 of the Natural Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Superintendent Myint 2 (U) Win Myint M President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Disaster Management House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Naing law President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Speaker of the Amyotha Hluttaw, the Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD 4 (U) Mann Win Khaing Than M upper house of the Myanmar 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and parliament President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Speaker of the Union Assembly, the Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD 5 (U) T Khun Myat M Joint House and Pyithu Hluttaw, the 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and lower house of the Myanmar President U Win Myint were detained. -

China in Burma: the Increasing Investment of Chinese Multinational Corporations in Burma’S Hydropower, Oil &Gas, and Mining Sectors

China in Burma: The increasing investment of Chinese multinational corporations in Burma’s hydropower, oil &gas, and mining sectors. Burma Project September 2007 Introductory research conducted by the Burma Project over the past three months has found more than 26 Chinese multinational corporations (MNCs) involved in more than 62 hydropower, oil & gas, and mining projects in Burma. The projects vary from small dams completed in the past decade to planned dual oil and gas pipelines across Burma to Yunnan province announced this year. Detailed information about many of these investments is not made available to affected communities or the general public, and we hope that the information here will stimulate additional discussion, research, and investigation into the conduct of Chinese MNCs in Burma. Amidst the recent attention to China’s moves to secure energy and resources throughout the world, Burma (also known as Myanmar) 1 has too often been overlooked. The Southeast Asian country is rich in natural resources, from dense forests and untouched rivers to vast untapped reserves of minerals, oil, and natural gas. Ruled by one of the world’s most notoriously brutal military regimes since 1962, 2 Burma exemplifies the corruption, misuse of resources, and environmental devastation of the “resource curse.” 3 Many western governments have imposed trade and investment sanctions on Burma, which has resulted in the departure of many western corporations; notable exceptions include Total of France and Chevron of the US. Meanwhile, as many Asian countries have begun to move outside their own territories in search of natural resources and energy, Burma has been a top destination. -

Affirmation of Shan Identities Through Reincarnation and Lineage of the Classical Shan Romantic Legend 'Khun Sam Law'

Thammasat Review 2015, 18(1): 1-26 Affirmation of Shan Identities through Reincarnation and Lineage of the Classical Shan Romantic Legend ‘Khun Sam Law’ Khamindra Phorn Department of Anthropology & Sociology Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University [email protected] Abstract Khun Sam Law–Nang Oo Peim is an 18th-century legend popular among people in all walks of life in Myanmar’s Shan State. To this day, the story is narrated in novels, cartoons, films and songs. If Romeo and Juliet is a classical romance of 16th-century English literature, then Khun Sam Law–Nang Oo Peim, penned by Nang Kham Ku, is the Shan equivalent of William Shakespeare’s masterpiece. Based on this legend, Sai Jerng Harn, a former pop-star, and Sao Hsintham, a Buddhist monk, recast and reimagined the legendary figure as a Shan movement on the one hand, and migrant Shans in Chiang Mai as a Shan Valentine’s celebration and protector of Khun Sam Law lineage on the other. These two movements independently appeared within the Shans communities. This paper seeks to understand how this Shan legend provides a basic source for Shan communities to reimagine and to affirm their identities through the reincarnation and lineage. The pop-star claims to be a reincarnation of Khun Sam Law, while the migrant Shans in Chiang Mai, who principally hail from Kengtawng, claim its lineage continuity. Keywords: Khun Sam Law legend, Khun Sam Law Family, Khun Sam Law movement, Sai Jerng Harn, Sao Hsintham, Kengtawng Thammasat Review 1 Introduction According to Khun Sam Law–Nang Oo Peim, a popular folktale originating in Myanmar’s Shan State, Khun Sam Law was a young merchant from Kengtawng, a small princedom under Mongnai city-state.