The Gateless Gate of Home Education Discovery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Harrison

COPYRIGHT 4th Estate An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.4thEstate.co.uk This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020 Copyright © Craig Brown 2020 Cover design by Jack Smyth Cover image © Michael Ochs Archives/Handout/Getty Images Craig Brown asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 9780008340001 Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008340025 Version: 2020-03-11 DEDICATION For Frances, Silas, Tallulah and Tom EPIGRAPHS In five-score summers! All new eyes, New minds, new modes, new fools, new wise; New woes to weep, new joys to prize; With nothing left of me and you In that live century’s vivid view Beyond a pinch of dust or two; A century which, if not sublime, Will show, I doubt not, at its prime, A scope above this blinkered time. From ‘1967’, by Thomas Hardy (written in 1867) ‘What a remarkable fifty years they -

Derbyshire Approach to Elective Home Education

The Derbyshire Approach to Elective Home Education Guidance for Parents/Carers February 2019 If you wish to receive this guidance document electronically please email [email protected] . An electronic version will allow you to open hyper-links to all the websites listed. The Department for Education has published new guidance for local authorities dated April 2019. Derbyshire County Council’s Guidance will be revised accordingly in the near future. PUBLIC PUBLIC 1 Dear Parent, Welcome to the Derbyshire Approach to Elective Home Education [EHE] – Guidance for Parents/Carers If you are reading this, you are likely to have either recently started home-educating your child, or are considering it as an option in the near future. The reasons that parents elect to home educate their child, or children, are extremely varied. Some parents make a philosophical, planned decision to home educate their child or children, and research the area in depth. However, we find that some parents turn to home education as a reaction to a school-based issue or dissatisfaction with a school environment. If there is a school-based issue, unless you really want to electively home educate and understand all the expectations on you, we strongly advise you not to withdraw your child from school until you have explored all the options with the school. Once your child is off a school roll, you are responsible for ensuring they have a full-time, suitable education. There are no automatic support services or resources for home education. If you want your child to take GCSEs, this can be very costly. -

Smash Hits Volume 60

35p USA $1 75 March I9-April 1 1981 W I including MIND OFATOY RESPECTABLE STREE CAR TROUBLE TOYAH _ TALKING HEADS in colour FREEEZ/LINX BEGGAR &CO , <0$& Of A Toy Mar 19-Apr 1 1981 Vol. 3 No. 6 By Visage on Polydor Records My painted face is chipped and cracked My mind seems to fade too fast ^Pg?TF^U=iS Clutching straws, sinking slow Nothing less, nothing less A puppet's motion 's controlled by a string By a stranger I've never met A nod ofthe head and a pull of the thread on. Play it I Go again. Don't mind me. just work here. I don't know. Soon as a free I can't say no, can't say no flexi-disc comes along, does anyone want to know the poor old intro column? Oh, no. Know what they call me round here? Do you know? The flannel panel! The When a child throws down a toy (when child) humiliation, my dears, would be the finish of a more sensitive column. When I was new you wanted me (down me) Well, I can see you're busy so I won't waste your time. I don't suppose I can drag Now I'm old you no longer see you away from that blessed record long enough to interest you in the Ritchie (now see) me Blackmore Story or part one of our close up on the individual members of The Jam When a child throws down a toy (when toy) (and Mark Ellen worked so hard), never mind our survey of the British funk scene. -

0 Well, That Didn't Go to Plan. General Election

0 Well, that didn’t go to plan. General election reflections: Simon Hughes, Nick Harvey, Liz Barker, Tony Greaves and more 0 All the presidents’ answers - Mark Pack 0 How we did Unite to Remain - Peter Dunphy Issue 399 - February 2020 £ 4 Issue 399 February 2020 SUBSCRIBE! CONTENTS Liberator magazine is published six/seven times per year. Subscribe for only £25 (£30 overseas) per year. Commentary.............................................................................................3 You can subscribe or renew online using PayPal at Radical Bulletin .........................................................................................4..7 our website: www.liberator.org.uk THE HORROR SHOW SEEN FROM OUTSIDE ..................................8..9 Professional roles meant Simon Hughes had to spend the general election campaign on Or send a cheque (UK banks only), payable to the sidelines for the first time in decades. What he saw of the Lib Dems alarmed him “Liberator Publications”, together with your name and full postal address, to: EIGHT ERRORS AND COUNTING ....................................................10..11 The Liberal Democrats got a lot wrong in the 2019 general election, many of them repeated mistakes never learnt from, says Nick Harvey Liberator Publications Flat 1, 24 Alexandra Grove LED BY DONKEYS ................................................................................12..13 London N4 2LF The general election saw the Liberal Democrats fail to find messages that resonated England with voters, and the campaign -

Circus Magazine/Shure Modern Circus/ 31 Music Makers Awards 1981

disappointing after the rasping " Evil Walks" and the infectious, Stones-like riffs of "COD." While the band's current approach is well-suited to its arena level of popularity, its calculation has replaced the edge of maniacism and sense of humor that by John Swenson the group once stood for. Even though they've progressed individually as musicians, it may well be that ACIDC have lost the identity AC/DC salute the British blues with which the late lead singer Bon Scott infused them. Stewart returns to classic form Rush - Exit... Stage Left (Mercury) At first glance this album may seem like just another Christmas-time live two-record package. But Exit .. Stage Left represents the coming of age of Canada's greatest band and one of the finest heavy-metal outfits to come out of the '70s proliferation of that style. The difference between this record and the first Rush live LP , All the World's a Stage, shows just how far the band has come in the last few years. Stage was an energetic but somewhat leaden account of the band's live strengths at a time when the members of Rush will now freely admit they were struggling. The sound quality of that first live record disappointed them, but the record consolidated their audience at a crucial point and gave them breathing space to come up with a fresh approach to their sound, which proved to be the turning point in A C/DC bang out quivering blues that serve as vehicles for Angus Young's Rush's career. -

Home Education

HOME EDUCATION: THE EXPERIENCE OF PARENTS IN A DIVIDED COMMUNITY Barbara Burke EdD Thesis submitted to Institute of Education, University of London Abstract This thesis focuses on the experiences of families who for a variety of reasons find themselves outside of the school system. It is concerned with families in one London borough who have decided not to send their children to school and to educate them at home. It examines the experiences of families who make a positive choice to home educate because of philosophical or religious beliefs but is particularly concerned with families who home educate following a series of difficulties with the school system, perhaps because their child has been bullied or because their child has special educational needs. The thesis contributes and adds to studies on home education as very little has been written about families who feel forced out of formal schooling. Only in the last few years has the diverse nature of the home educating population in the UK started to be acknowledged in the professional literature. The research for this study was carried out between 2003 and 2005. When the research was started there were 38 families with 55 children known to the local authority to be home educating. Of these 38 families, 17 were interviewed in order to gain the perceptions and experiences of parents. In this thesis, four key areas of home education are considered. Firstly, the reasons that parents give for home education are reviewed. Secondly, the educational experience of home education is considered, including the methods of teaching that parents choose, as well as the academic achievement of those home educated. -

Read an Extract

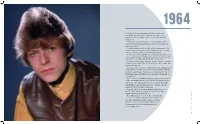

1964 FIRED by his live experiences with The Konrads and searching for an escape from his ad agency job, David resolves to make a go of music with George Underwood. David is the focal point on vocals and saxophone when they form The King Bees with three older musicians, playing hard-edged R&B. A cheeky appeal for financial backing to magnate John Bloom results in contact with agent/manager Leslie Conn, who also handles another unknown, Marc Bolan. Conn signs a deal with Decca for a single, ‘Liza Jane’, with ‘Louie, Louie Go Home’ on the B-side. David leaves his day job and becomes a fully fledged professional musician. Promotion for the single includes an appearance on Ready Steady Go! and BBC TV’s The Beat Room, with David also playing saxophone. The failure of ‘Liza Jane’ to chart leads to the disbandment of The King Bees. Conn has already hooked David up with The Manish Boys from Kent, though tensions arise over billing and David finds himself shuttling between Bromley and their base in Maidstone. Davie Jones & The Manish Boys play R&B venues all over south-east England but struggle to make an impact. David makes his first appearance at Soho club the Marquee, which will become a significant venue in his life. He also meets girlfriend Dana Gillespie there. In an attempt to create a stir, David forms The Society ANY DAY NOW l DAVID BOWIE l THE LONDON YEARS NOW l DAVID ANY DAY For The Prevention Of Cruelty To Long-Haired Men, again appearing on national TV. -

JÖRGEN ANGEL Doesn't Need to Tell You Stories to Earn Your Respect. All

CLASSIC ROCK ROCK OF AGES JÖRGEN ANGEL doesn’t need to tell you stories to earn your respect. All he needs to do is show you 50,000 photographs of the biggest rock acts the world has ever known. The Dane, who photographed Led Zeppelin’s first ever jam, talks to Jaideep V.G. about classic rock and the time Angus Young dropped his pants. eptember 7, 1968 was a Saturday and Jörgen Angel was a Jaideep V.G.: Your first pictures were of Sonny and Cher. You were disappointed 17-year-old kid. As on most Saturday nights, Jörgen just 14 when you took those pictures, what was it like? Shad landed up at the Gladsaxe Teen Club in Copenhagen with his Jörgen Angel: It was not at a concert. It was a press reception that mother’s holiday camera and father’s old flash. He’d been told The somebody took me along to and I took pictures with my Kodak Yardbirds would be jamming at the Gladsaxe that night, but when he Instamatic. They (the pictures) were not very good. This was at an saw a little sign at the club announcing some band called The New outdoor thing at the Tivoli Garden. I got to meet the both of them and Yardbirds, he was sure no one from the supergroup he worshipped Cher’s younger sister. They signed some of my records. would be on stage. He was right, there was just Jimmy Page at the club that night. J.V.G.: Did you talk to them at all? The other three musicians were called Robert Plant, John Bonham and J.A.: I didn’t talk very much. -

Bonham-Article.Pdf

COVER FEATURE 28 TRAPS TRAPSMAGAZINE.COM THE JOHN BONHAM STORY ManCityCity BoyCountry Country BY CHRIS WELCH WITH ANDY DOERSCHUK JON COHAN JARED COBB & KAREN STACKPOLE autum 2007 TRAPS 29 30-49 Bonham 7/19/07 3:29 PM Page 30 JOHN BONHAM PREFACE A SLOW NIGHT AT THE MARQUEE As a Melody Maker reporter during the 1960s, I vividly remember the moment when a review copy of Led Zeppelin’s eponymous debut album arrived at the office. My colleague and fellow scribe Tony Wilson had secured the precious black vinyl LP and dropped it onto the turntable, awaiting my reaction. We were immediately transfixed by the brash, bold sounds that fought their way out of the lo- fi speakers – Robert Plant’s screaming vocals, the eerie Hammond organ sounds of John Paul Jones, and Jimmy Page’s supreme guitar mastery. But amid the kaleidoscope of impressions, the drums were the primary element that set pulses racing. We marveled at the sheer audacity, the sense of authority, the spatial awareness present on every track. Within moments, John Bonham’s cataclysmic bass drum triplets and roaring snare rolls had signaled a new era of rock drumming. The first time I saw Bonham up close was in December 1968, at The Marquee Club on Soho’s Wardour Street. While The Marquee has long held a mythical status in the rich history of the London rock scene – hosting early appearances by such legendary bands as The Who and The Rolling Stones – it was actually a dark and rather cramped facility with a tiny stage that fronted an even stuffier dressing room. -

BOOKS Are Paperback Unless Stated Otherwise. Postage Extra Please Ask Before Ordering. Spiders

All BOOKS are paperback unless stated otherwise. Postage extra please ask before ordering. Spiders - 45rpm Record adapters plastic B675- bag of 100 M £3.00 B220 BOOK: RICK NELSON - Bear Family book from Last Time Around box set 140ppHB £15.00 BOOK: LOTTE LENYA - Bear Family book from box set 140pp £10.00 BOOK: BUDDY HOLLY -Remembering Buddy HB signed by Crickets, authors + photo & CD Ltd ed # 32 £75.00 BOOK: Six More From BUDDY HOLLY - 1960s sheet music 6 songs £15.00 BOOK: Rockabilly Heaven by Side Holmes - Story of The Cavaliers Grourp 1956-1964 PB with free CD of music £16.00 BOOK: Rock Handbook - various authors A4+ format with biogs of just about everyone up to 80s £10.00 BOOK: Little Richard Life and Times -Charles White. Crazy singer, crazy author, perfect match! Autographed to Giselle £15.00 BOOK: Big Bill Broonzy - I Feel So Good by Rob Riseman - University of Chicago £20.00 BOOK: Restless Generation by Pete Frame - Great summary of 50s Britain £20.00 BOOK: Crickets Fact File: Personnel, Tour dates, Songwriter Credits, Recordings sessions Great stuff, photocopy A4 £10.00 BOOK: Screaming Lord Sutch: LIFE AS SUTCH Offiocial Autobiography of a Monster Raving Loony HB 1991 £12.00 BOOK: ELVIS IN HIS OWN WORDS - Quotes and pictures - Mick Farren & Pearce Marchbank Omnibus PB £8 BOOK: AS SUTCH - The political manifesto of the Official Monster Raving Loony Party. Fun/serious stuff. PB Ex £5.00 Baseball cap MICKEY LEE LANE Hemsby, Norfolk May 1997 Black M £5.00 B216 BOOK: A Guide to collecting his Master's voice 'NIPPER' Souvenirs 0 9509293 1 X EDGE & PETTS EMI M £20.00 B019 BOOK: A TWIST OF LENNON 0 352 30196 1 LENNON, Cynthia Star M £4.00 B189 BOOK: ABBEY ROAD - Official history of the studio 0 85059 810 9 SOUTHALL, Brian PSL M £10.00 B051 BOOK: Alan Mann's A-Z BUDDY HOLLY (1st edition) none MANN, Alan Mann M £5.00 B008 BOOK: ALEXIS KORNER, The biography 0 7475 3163 3 SHAPIRO, Harry Bloomsbury M £9.00 B072/F BOOK: AS TIME GOES BY (Beatles) 0 70667 0027 9 TAYLOR, Derek Davis-Poynter M £3.00 B192 BOOK: Beatles An Illustrated Diary 0 85965 070 7 FULPEN, H.V. -

Summerhill Court Victory

# 2299 Spring 2000 $4.95 TheThe EducationEducation RevolutionRevolution With special CHANGING SCHOOLS section The Magazine of the Alternative Education Resource Organization (Formerly AERO-gramme) COVER PHOTO Cover story: Summerhill wins watershed court victory. Two happy students at Summerhill (this is already scanned in #28) #27TIF Contents: SUMMERHILL WINS IN COURT! AERO NEEDS FEEDBACK FROM YOU AERO RECEIVES THREE GRANTS Mail and Communications Book Reviews Home Education News Public Alternatives Alumni Stories International News and Communications Australia, Ecuador England, France, Germany, Latvia, New Zealand, Northern Ireland. Norway. West Bank, Russia, Turkey, Ukraine Teachers, Jobs, and Internships Conferences Special Section:CHANGING SCHOOLS High Stakes Tests: A Harsh Agenda for America's Children Remarks by U.S. Senator Paul D. Wellstone Letter to the Editor of the New York Times about Commissioner Mills’ Decision about Public Alternative Schools, By Jerry Mintz In Your Backyard: Florida's Online Education Experiment The Three Xs, by Idit Harel Interview With Brian Kearsey About the Founding of Crossroads School, Brewster, NY Talk at Manitoba Alternative Education Association New Items Announcing two great new books on educational alternatives AERO Books, Videos, Subscription, Ordering Information The Education Revolution The Magazine of the Alternative Education Resource Organization (Formerly AERO-gramme) 417 Roslyn Rd., Roslyn Heights, NY 11577 ISSN # 10679219 phone: 516-621-2195 or 800-769-4171 fax: 516-625-3257 e-mail: -

Elective Home Education in Nottingham

Elective Home Education in Nottingham “Elective” means “chosen”: the parents take direct responsibility for organising their child’s education, rather than leaving it to a school. (It’s not the same as when a school child is ill for a long time and the Council provides a tutor, although this is confusingly also known as “home education”.) Useful contacts and further information Nottingham City Council EMHE Yahoo group https://groups.yahoo. EHE Department com/neo/groups/emhe/info Elective Home Education On Facebook, there are a couple of Access and Inclusion Nottingham/Nottinghamshire groups Children & Adults, sharing info similar to EMHE - but the Loxley House LH Box 6, Facebook groups are invitation-only, so Station Street, EMHE is a good place to start. Nottingham NG2 3NG Non-School Nottingham website: Gives Tel: 0115 876 4685/876 5946 overview of local meet-ups and can be seen without “joining” or “subscribing to” Email: electivehomeeducation@ anything. Some groups welcome visiting nottinghamcity.gov.uk parents who are still making up their minds. Web: www.nottinghamcity.gov.uk/ehe www.non-school-nottingham.org.uk Local, online Local, by phone East Midlands Home Education (EMHE) Education Otherwise email list: Local parents swap information https://educationotherwise.org has a on meet-ups, events and resources, helpline on 0845 478 6345. They should share advice and support, organise be able to put you in touch with a parent group discounts, etc. Open to all home volunteer in the Nottingham area who is educating parents and those beginning happy to chat on the phone about home to consider it.