Memory, Movement, Mobility: Affect-Full Encounters with Memory in Singapore Danielle Drozdzewski

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Changi Chapel and Museum 85

LOCALIZING MEMORYSCAPES, BUILDING A NATION: COMMEMORATING THE SECOND WORLD WAR IN SINGAPORE HAMZAH BIN MUZAINI NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2004 LOCALIZING MEMORYSCAPES, BUILDING A NATION: COMMEMORATING THE SECOND WORLD WAR IN SINGAPORE HAMZAH BIN MUZAINI B.A. (Hons), NUS A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2004 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ‘Syukor Alhamdulillah!’ With the aid of the Almighty Allah, I have managed to accomplish the writing of this thesis. Thank god for the strength that has been bestowed upon me, without which this thesis might not have been possible indeed. A depth of gratitude to A/P Brenda Yeoh and A/P Peggy Teo, without whose guidance and supervision, I might not have been able to persevere with this endeavour. Thank you for your limitless patience and constant support throughout the two years. To A/P Brenda Yeoh especially: thanks for encouraging me to do this and also for going along with my “conference-going” frenzy! It made doing my Masters all that more exciting. A special shout-out to A. Jeyathurai, Simon Goh and all the others at the Singapore History Consultants and Changi Museum who introduced me to the amazing, amazing realm of Singapore’s history and the wonderful, wonderful world of historical research. Your support and friendship through these years have made me realize just how critical all of you have been in shaping my interests and moulding my desires in life. I have learnt a lot which would definitely hold me in good stead all my life. -

Travel Itinerary

Travel Itinerary Page 1 of 5 PROGRAM: 16 DAYS / 13 NIGHTS ROUNDTRIP KUALA LUMPUR - CAMERON HIGHLANDS - MALACCA - JOHOR - SINGAPORE DAY 1 - WEDNESDAY 3 MARCH - DUMFRIES-GLASGOW & GALASHIELS-GLASGOW (1) Coach transfer from Dumfries to Glasgow airport (1) Coach transfer from Galashiels to Glasgow airport TO KUALA LUMPUR (VIA DUBAI) Fly from Glasgow airport Dubai on Emirates Airlines Depart Glasgow Emirates Airlines EK28 13:05 DAY 2 - THURSDAY 4 MARCH - DUBAI Arrive Dubai 00:25 Change your flight to Kuala Lumpur Depart Dubai Emirates Airlines EK346 03:10 Arrive Kuala Lumpur 14:05 Meeting, assistance on arrival and transferred to your hotel. Overnight stay at Shangri-La Kuala Lumpur for 3 nights (5 Star Hotel - Superior Room) DAY 3 - WEDNESDAY 24 FEB - KUALA LUMPUR (B/L) They say the best way to get to know a new city is through a tour. This tour will unveil the beauty and charm of the old and new Kuala Lumpur Known as the ‘Garden City of Lights’. See the contrast of the magnificent skyscrapers against building of colonial days. Places visited: Petronas Twin Towers (Photo stop) King’s Palace (Photo stop) Independent Square National Monument Royal Selangor Pewter After tour return to hotel and free at leisure. In the evening transfer to Seri Melayu Restaurant where you can savor a wide array of local dishes and delights, at the same time be entertained with a cultural show. Overnight stay at Shangri-La Kuala Lumpur. DAY 4 - THURSDAY 25 FEB - KUALA LUMPUR (B) TRAVELSERV Trademark Registered No: 2536073 Address: 38 Bridge Farm Close, Mildenhall, Suffolk. -

From Orphanage to Entertainment Venue: Colonial and Post-Colonial Singapore Reflected in the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus

From Orphanage to Entertainment Venue: Colonial and post-colonial Singapore reflected in the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus by Sandra Hudd, B.A., B. Soc. Admin. School of Humanities Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the qualification of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania, September 2015 ii Declaration of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the Universityor any other institution, except by way of backgroundi nformationand duly acknowledged in the thesis, andto the best ofmy knowledgea nd beliefno material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text oft he thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. �s &>-pt· � r � 111 Authority of Access This thesis is not to be made available for loan or copying fortwo years followingthe date this statement was signed. Following that time the thesis may be made available forloan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. :3 £.12_pt- l� �-- IV Abstract By tracing the transformation of the site of the former Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus, this thesis connects key issues and developments in the history of colonial and postcolonial Singapore. The convent, established in 1854 in central Singapore, is now the ‗premier lifestyle destination‘, CHIJMES. I show that the Sisters were early providers of social services and girls‘ education, with an orphanage, women‘s refuge and schools for girls. They survived the turbulent years of the Japanese Occupation of Singapore and adapted to the priorities of the new government after independence, expanding to become the largest cloistered convent in Southeast Asia. -

WARTIME Trails

history ntosa : Se : dit e R C JourneyWARTIME into Singapore’s military historyTRAI at these lS historic sites and trails. Fort Siloso ingapore’s rich military history and significance in World War II really comes alive when you make the effort to see the sights for yourself. There are four major sites for military buffs to visit. If you Sprefer to stay around the city centre, go for the Civic District or Pasir Panjang trails, but if you have time to venture out further, you can pay tribute to the victims of war at Changi and Kranji. The Japanese invasion of February 1942 February 8 February 9 February 10 February 13-14 February 15 Japanese troops land and Kranji Beach Battle for Bukit Battle of Pasir British surrender Singapore M O attack Sarimbun Beach Battle Timah PanjangID Ridge to the JapaneseP D H L R I E O R R R O C O A H A D O D T R E R E O R O T A RC S D CIVIC DISTRICT HAR D R IA O OA R D O X T D L C A E CC1 NE6 NS24 4 I O Singapore’s civic district, which Y V R Civic District R 3 DHOBY GHAUT E I G S E ID was once the site of the former FORT CA R N B NI N CC2 H 5 G T D Y E LI R A A U N BRAS BASAH K O O W British colony’s commercial and N N R H E G H I V C H A A L E L U B O administrative activities in the C A I E B N C RA N S E B 19th and 20th century, is where A R I M SA V E H E L R RO C VA A you’ll find plenty of important L T D L E EY E R R O T CC3 A S EW13 NS25 2 D L ESPLANADE buildings and places of interest. -

Factsheet – Other Activities

Factsheet – Other Activities NHB. Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence, Dr Tony Tan Keng Yam, will officially open the WWII Interpretative Centre at 31K Pepys Road on 15 Feb 2002. Called Reflections at Bukit Chandu, its six galleries will showcase the historical context of the Battle of Pasir Panjang in relation to other battles fought in Singapore in 1942. The Centre will also highlight the role of the Malay Regiment and the heroism of its men in defending Singapore against the Japanese forces. For more details, please refer to TOTAL DEFENCE DAY 2002: OPENING OF REFLECTIONS AT BUKIT CHANDU, A WWII INTERPRETATIVE CENTRE AT 31K PEPYS ROAD. Examples of activities organised by the museums under NHB in conjunction with Total Defence Day are a mini-display on Total Defence at the Singapore History Museum, an exhibition of rare sketches drawn during the Japanese Occupation at the National Archives of Singapore foyer, and a showcase of stamps related to the war at an exhibition on the 60th anniversary of the fall of Singapore at the Singapore Philatelic Museum. In addition, NHB and ACT 3 have collaborated on the production of a Total Defence-related performance for schools. Heritage Services Division of NHB will also launch a new publication, Singapore's 100 Historic Places. Please refer to TOTAL DEFENCE DAY 2002: ACTIVITIES UNDER NATIONAL HERITAGE BOARD (NHB) for details. STB. On 15 Feb 2002, BG (NS) George Yeo, Minister for Trade and Industry, will officially launch the Johore Battery site. The Johore Battery, built in 1939 by the British, is a underground labyrinth of tunnels that used to store ammunition for 15-inch guns during WWII. -

MASTEREIGN ENRICHMENT GROUP ENRICHMENT GUIDE Top Quality Holistic Programme Through Strategic Collaboration and Seamless Integration with Industry Specialists

MASTEREIGN ENRICHMENT GROUP ENRICHMENT GUIDE Top quality holistic programme through strategic collaboration and seamless integration with industry specialists. MASTEREIGN.COM/BROCHURES ABOUT MASTEREIGN We are the leading provider of holistic enrichment programmes in Singapore. From success to significance, we enrich lives through a fruitful, well-rounded and satisfying learning journey. It is our mission to stay relevant to the needs of schools in Singapore, providing top quality holistic programmes through strategic collaboration and seamless integration with industry specialists. OUR VISION OUR CULTURE Asia Pacific’s best and most admired holistic As a united tribe, we have a continuous growing enrichment group. organizational structure that does not stifle but instead encourage each individual to be productive, innovative, and enterprising. That OUR MISSION means we have the courage to take creative To thrive as a leading holistic tribe with a heart risks and embrace change. to serve and a passion to make a positive impact in Singapore and the region. Our leaders guide the way, then we follow and forge ahead as one towards the same glorious The journey is from success to significance. vision. We create value, first for our customers, then our co-workers, and finally our company and corporate share holders. We recognize and reward good contributions. We nurture and celebrate talents and achievements. We know that the journey ahead is not without obstacles, but our attitude is that, in spite of it all, we will celebrate life and cheer everyone in the tribe to overcome and finish strong. 2 | WWW.MASTEREIGN.COM OUR CORE VALUES Since 1997, we have served at least one million RESPONSIBILITY youths and adults in over three hundred We can be trusted to do what we have fifty government schools and educational promised. -

Singapore Fall & Winter Guide 2011 – 2012

SINGAPORE FALL & WINTER GUIDE 2011 – 2012 The best places to eat, sleep and play in Singapore this fall and winter With more than 50 million reviews and opinions, TripAdvisor makes travel planning a snap for the 50 million travelers visiting our site each month. Think before you print. And if you do print, print double-sided. INTRODUCTION TripAdvisor, the most trusted source for where to eat, sleep and play in thousands of destinations around the world, has collected the best insider tips from its 50 million monthly visitors to produce a unique series of travel guides. In addition to the best hotels, restaurants and attractions for every type of traveler, you’ll get great advice about what to pack, how to get around and where to find the best views. Be sure to check out the guides at www.tripadvisor.com. You’ll find reviews for more than Inside 520,000 hotels, 125,000 vacation rentals, 155,000 attractions and 715,000 restaurants on TripAdvisor.com. Learn from other travelers SINGAPORE what to expect before you make your plans. Singapore may have a Westernized facade, with its modern skyscrapers and bustling business folk, but lurking not far beneath is a world of beauty and history. With a diverse multicultural population, Singapore is home to Little India, PACKING TIPS Chinatown and an Arab Quarter. At the center lies the Colonial District, a remnant of the not-too-long-ago past, .1 “Singapore has a warm and humid when Singapore was a British colony. The mix of cultures climate throughout the year, thus is evident everywhere, even in the language, the unofficial light clothing made from natural fabrics like cotton is best for everyday “Singlish,” which is an amalgamation of English, Chinese wear.”—TripAdvisor Member, grammar, Malay expressions and Hokkien slang. -

Singapore Armed Forces Veterans' League Annual

SINGAPORE ARMED FORCES VETERANS’ LEAGUE ANNUAL REPORT – 2018/2019 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 In line with Singapore’s objective to promote racial harmony, SAF Veterans’ League (SAFVL) had always been at the fore front promoting racial integration and cohesion. Every year, we organised festivities covering our four diversified racial groups, which was well attended by all four racial groups. This year in particular after the overseas trip to VECONAC meeting in Laos we saw our members’ spouse and lady members becoming a cohesive group. We have also been very successful in our contributions towards our national education efforts on national defence, and the number of assignments had been very encouraging. All these events were well supported by members with their active participation and contribution. 1.2 Like in previous years, SAFVL had been very focused on our objectives and continued to work towards the following areas: - Remaining engaged, relevant and current to the SAF and the Nation. - Be a responsible member of our international and regional veterans’ community. - Be a role model and ambassador towards National Education. - Imbue in our members the concept of active aging. - Caring for our veterans. 1.3 Our ties with the Singapore Armed Forces and Ministry of Defence remain strong and we are looking forward to elevate the status of SAFVL and contribute more meaningfully to both our parent organisations and be appropriately recognised. 2. INTERNATIONAL VETERANS EVENTS. VETERANS CONFEDERATION OF ASEAN COUNTRIES (VECONAC) 18TH GENERAL ASSEMBLY AT LAOS, VIENTIANE 10th to 13th DECEMBER 2018 2.1 A total of 44 SAFVL members and spouses attended the General Assembly in Laos. -

20180407 Circuitparkmap HOSP HR

GRAND PARK BRAS BASAH RD CITY HALL CAPITOL PIAZZA RAFFLES HOTEL PENINSULA FAIRMONT EXCELSIOR HOTEL PENINSULA PLAZA RAFFLES CITY NORTH BRIDGE RD BEACH RD STAMFORD RD COLEMAN ST SWISSÔTEL THE STAMFORD ST. ANDREW’S CATHEDRAL JW MARRIOTT HOTEL NICOLL HIGHWAY SOUTH BEACH SUNTEC CITY THE ADELPHI OPHIR RD N PADANG SUPREME COURT STAGE CIVILIAN WAR MEMORIAL OF SINGAPORE SINGAPORE MEMORIAL RECREATION SUPREME COURT LANE PARLIAMENT PL CLUB FOUNTAIN SUNTEC CONVENTION OF WEALTH & EXHIBITION CENTRE D V AY L B HW NATIONAL GALLERY ST. ANDREW’S RD IG C L H I SINGAPORE OL TURN 3 L IC B N U ONE RAFFLES P E LINK R PARLIAMENT OF SINGAPORE THE PADANG VILLAGE TEMASEK BLVD CONRAD STAGE CENTENNIAL VE TEMASEK AVE SINGAPORE RI SLING T D GH AU SINGAPORE NN CO MARINA MANDARIN VICTORIA THEATRE CRICKET CLUB THE CENOTAPH CENTENNIAL AND CONCERT HALL TOWER EMPRESS TURN 2 STAGE RAFFLES AVE ASIAN PAN PACIFIC CIVILISATIONS ESPLANADE PARK MUSEUM MARINA SQUARE SHEARES PIT EXIT ESPLANADE THEATRES ON THE BAY MILLENIA WALK RAFFLES BOULEVARD FULLERTON ROAD ANDERSON SINGAPORE BRIDGE RIVER CAVENAGH BRIDGE CAVENAGH GE ID TURN 1 TURN 1 R B MANDARIN ORIENTAL E E IL B U ESPLANADE DR J ESPLANADE OUTDOOR THEATRE SUNSET STAGE THE FULLERTON HOTEL THE RITZCARLTON MILLENIA ONE FULLERTON MARINA BAY THE FLOAT MARINA BAY FULLERTON RD 1 2 3 SINGAPORE FLYER PIT STRAIGHT ARTSCIENCE E PIT ENTRY MUSEUM G ID BR X LI HE BAYFRONT AVE ZONE 1 ZONE 2 ZONE 3 ZONE 4 PADDOCK ZONE LEGEND ZONES RESTRICTED AREA TURN 23 1 START END 2 PODIUM RACE DIRECTION 3 EAST COAST PARKWAY ECP MARINA BAY SANDS THIS MAP IS NOT DRAWN TO SCALE. -

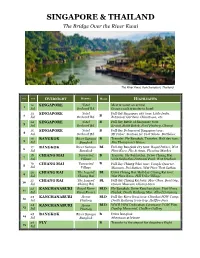

SINGAPORE & THAILAND the Bridge Over the River Kwai

SINGAPORE & THAILAND The Bridge Over the River Kwai The River Kwai, Kanchanaburi, Thailand DAY DATE OVERNIGHT HOTELS MEALS HIGHLIGHTS 12 SINGAPORE Yotel Meet & assist on arrival 1 Jul Orchard Rd. Group coach transfer to hotel 13 SINGAPORE Yotel Full day Singapore city tour: Little India. 2 B Jul Orchard Rd. Botanical Gardens. Chinatown, etc. 14 Yotel B Full day Battle of Singapore tour: 3 SINGAPORE Jul Orchard Rd. Kranji, Bukit Batok, Ford Factory, Changi 15 Yotel B Full day Defences of Singapore tour: 4 SINGAPORE Jul Orchard Rd. Mt Faber. Sentosa Isl. Fort Siloso. Battlebox 16 BANGKOK River Suraya B Transfer. Fly Bangkok. Transfer. Half day tour: 5 Jul Bangkok Jim Thompson’s House 17 River Suraya BL Full day Bangkok city tour: Royal Palace, Wat 6 BANGKOK Jul Bangkok Phra Kaeo, Pho & Arun. Floating Market 18 Tamarind B Transfer. Fly Sukhothai. Drive Chiang Mai 7 CHIANG MAI Jul Village Visit Sukhothai National Park. Wat Srichum 19 Tamarind B 8 CHIANG MAI Full day Chiang Mai tour: Temple Quarter. Jul Village Museum. Doi Suthep, Wat Phra That Suthep 20 The Legend BL Drive Chiang Rai. Half day Chiang Rai tour: 9 CHIANG RAI Jul Chiang Rai Wat Phra Kaeo. Hill Tribe Village 21 The Legend BL Full day Chiang Rai tour: Mae Chan. Boat trip, 10 CHIANG RAI Jul Chiang Rai Opium Museum. Chiang Saen 22 Royal River BLD Fly Bangkok. Drive Kanchanaburi. Visit Nong 11 KANCHANABURI Jul Kwai Resort Pladuk. Death Railway Mus. Allied Cemetery 23 Home BLD Full day River Kwai tour: Chunkai POW Camp, 12 KANCHANABURI Jul Phutoey Death Railway train trip. -

55 Best Tourist Places to Visit in Singapore

55 Best Tourist Places to Visit in Singapore Be it the beautiful lovely and exemplary places to visit in Singapore, shopping frenzy, delectable culinary delights, awe-inspiring museums, adventurous theme parks, exotic gardens- Singapore have you all covered. Must Visit Places: Thrillophilia Recommendation 01. Universal Studios Singapore 02. Singapore Flyer 03. Gardens By The Bay 04. Night Safari Nocturnal Wildlife Park 05. Singapore Zoo 06. Marina Bay 07. Infinity Pool at Marina Bay Sands 08. Merlion Park 09. Sentosa Island 10. Jurong Bird Park 11. Clarke Quay 12. Underwater World 13. Experience Little India 14. River Safari, Singapore 15. S.E.A. Aquarium 16. Visit a Casino 17. Tree-top Walk at MacRitchie Reservoir 18. Chinatown 19. Madame Tussauds Wax Museum 20. Indoor Sky Diving 21. Adventure Cove Waterpark 22. Tiger Sky Tower 23. Driving on the F1 track 24. Visit Tiger Brewery 25. Trick Eye Museum 26. Butterfly Park And Insect Kingdom 27. National Orchid Garden 28. Singapore Botanic Gardens 29. Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum 30. Asian Civilisations Museum 31. Raffles Hotel 32. Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve 33. Bukit Timah Nature Reserve 34. Changi Chapel and Museum 35. The Helix Bridge 36. Explore Coney Island 37. Waterfront Promenade 38. Arab Street 39. Peranakan Museum 40. Sri Mariamman Temple 41. National Gallery Singapore 42 Armenian Church 43. CÉ LA VI Singapore 44. Kong Meng San Phor Kark See Monastery 45. Bukit Batok Hill 46. Siloso Beach 47. Kusu Island 48. Changi Beach 49. Bugis Street 50. Palawan Beach 51. Pulau Ubin 52. Tanjong Beach 53. Lazarus Island 54. -

Getting There

Travel SATURDAY, JULY 10, 2010 The guns at Fort Siloso protected the entrance to Keppel Harbor at the time of the Japanese attack on Singapore in 1941. PHOTO COURTESY OF SENTOSA Information National Museum of Singapore Singapore History Gallery 93 Stamford Rd, Singapore 178897 Opening hours: Daily from 10am to 6pm The rest is Admission: Adult S$8 (includes Singapore Living Galleries) MRT Dhoby Ghaut or Bras Basah stations Reflections at Bukit Chandu 31-K Pepys Rd, Singapore 118458 Opening hours: Tuesdays to Sundays from 9am to 5:30pm Admission: Adult S$2 MRT HarbourFront Station and take bus SBS bus 10, 30, 143 or SMRT bus 188 from HarbourFront Centre The Battle Box history 51 Canning Rise, Singapore 179872 Opening hours: Daily from 10am to 6pm Singapore’s World War II sites, museums and tours challenge preconceived Admission: Adult S$8 ideas of how the conflagration unfolded in the city-state MRT Dhoby Ghaut or Bras Basah stations Contrary to popular belief, Singapore’s guns, like this replica at Fort Kranji War Cemetery BY TONY PHIllIps Siloso, were not pointing the wrong way in 1941. 9 Woodlands Road, Singapore 738656 STAFF REPORTER PHOTO COURTESY OF SENTOSA Opening hours: Daily from 7am to 6pm Admission: Free MRT Kranji Station veryone knows that World War private bus to the former British command allied servicemen who died fighting in admission fee includes a tour with a guide II in the Far East began with post on Mount Faber, which provides a Southeast Asia or in its prison camps. who describes the gruesome methods used Fort Siloso the Japanese attack on Pearl panorama of the island from Johor to the The Kranji War Memorial overlooks the by the Japanese secret police to extract 33 Allanbrooke Road, Singapore 099981 Harbor on Dec.