(Metrosideros Polymorpha) in Hawaii: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metrosideros Polymorpha Gaudich

Metrosideros polymorpha Gaudich. JAMES A. ALLEN Paul Smiths College, Paul Smiths, NY MYRTACEAE (MYRTLE FAMILY) Metrosideros collina (J.R. and G. Forst.) A. Gray subsp. polymorpha (Gaud.) Rock. (Little and Skolmen 1989). See also the extensive list of synonyms in Wagner and others (1990) Lehua, ‘ohi’a Metrosideros is a genus of about 50 species. With the excep- hybridization and genetic polymorphism is unknown (Wagner tion of one species found in South Africa, all grow in the and others 1990). Pacific from the Philippines, through Papua New Guinea, to The heartwood is reddish brown, heavy (specific gravity New Zealand and on high volcanic islands (Wagner and oth- of about 0.70), of fine and even texture, very hard, and strong. ers 1990). Five species occur in the Hawaiian Islands (Wag- Native Hawaiians used the wood extensively for construction, ner and others 1990). Metrosideros polymorpha is native to household implements, and carvings. Principal modern uses Hawaii, where it grows on all the main islands except Niihau include flooring, marine construction, pallets, fenceposts, and and Kahoolawe. It is the most abundant and widespread fuelwood. The wood’s limitations include excessive shrinkage M native tree in Hawaii (Adee and Conrad 1990) and grows in in drying, density, and the difficulty and expense of harvesting association with numerous species in both wet and relatively in low-volume stands (Adee and Conrad 1990, Little and Skol- dry forests. men 1989). Today, M. polymorpha is perhaps most highly val- Metrosideros polymorpha is a slow-growing, evergreen ued in Hawaii for uses in watershed protection, aesthetics, and species capable of reaching 24 to 30 m in height and about 1 m habitat for native birds, including several endangered species. -

Genera in Myrtaceae Family

Genera in Myrtaceae Family Genera in Myrtaceae Ref: http://data.kew.org/vpfg1992/vascplnt.html R. K. Brummitt 1992. Vascular Plant Families and Genera, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew REF: Australian – APC http://www.anbg.gov.au/chah/apc/index.html & APNI http://www.anbg.gov.au/cgi-bin/apni Some of these genera are not native but naturalised Tasmanian taxa can be found at the Census: http://tmag.tas.gov.au/index.aspx?base=1273 Future reference: http://tmag.tas.gov.au/floratasmania [Myrtaceae is being edited at mo] Acca O.Berg Euryomyrtus Schaur Osbornia F.Muell. Accara Landrum Feijoa O.Berg Paragonis J.R.Wheeler & N.G.Marchant Acmena DC. [= Syzigium] Gomidesia O.Berg Paramyrciaria Kausel Acmenosperma Kausel [= Syzigium] Gossia N.Snow & Guymer Pericalymma (Endl.) Endl. Actinodium Schauer Heteropyxis Harv. Petraeomyrtus Craven Agonis (DC.) Sweet Hexachlamys O.Berg Phymatocarpus F.Muell. Allosyncarpia S.T.Blake Homalocalyx F.Muell. Pileanthus Labill. Amomyrtella Kausel Homalospermum Schauer Pilidiostigma Burret Amomyrtus (Burret) D.Legrand & Kausel [=Leptospermum] Piliocalyx Brongn. & Gris Angasomyrtus Trudgen & Keighery Homoranthus A.Cunn. ex Schauer Pimenta Lindl. Angophora Cav. Hottea Urb. Pleurocalyptus Brongn. & Gris Archirhodomyrtus (Nied.) Burret Hypocalymma (Endl.) Endl. Plinia L. Arillastrum Pancher ex Baill. Kania Schltr. Pseudanamomis Kausel Astartea DC. Kardomia Peter G. Wilson Psidium L. [naturalised] Asteromyrtus Schauer Kjellbergiodendron Burret Psiloxylon Thouars ex Tul. Austromyrtus (Nied.) Burret Kunzea Rchb. Purpureostemon Gugerli Babingtonia Lindl. Lamarchea Gaudich. Regelia Schauer Backhousia Hook. & Harv. Legrandia Kausel Rhodamnia Jack Baeckea L. Lenwebia N.Snow & ZGuymer Rhodomyrtus (DC.) Rchb. Balaustion Hook. Leptospermum J.R.Forst. & G.Forst. Rinzia Schauer Barongia Peter G.Wilson & B.Hyland Lindsayomyrtus B.Hyland & Steenis Ristantia Peter G.Wilson & J.T.Waterh. -

Re-Establishing North Island Kākā (Nestor Meridionalis Septentrionalis

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Re-establishing North Island kākā (Nestor meridionalis septentrionalis) in New Zealand A thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science In Conservation Biology Massey University Auckland, New Zealand Tineke Joustra 2018 ii For Orlando, Aurora and Nayeli “I don’t want my children to follow in my footsteps, I want them to take the path next to me and go further than I could have ever dreamt possible” Anonymous iii iv Abstract Recently there has been a global increase in concern over the unprecedented loss of biodiversity and how the sixth mass extinction event is mainly due to human activities. Countries such as New Zealand have unique ecosystems which led to the evolution of many endemic species. One such New Zealand species is the kākā (Nestor meridionalis). Historically, kākā abundance has been affected by human activities (kākā were an important food source for Māori and Europeans). Today, introduced mammalian predators are one of the main threats to wild kākā populations. Although widespread and common throughout New Zealand until the 1800’s, kākā populations on the mainland now heavily rely on active conservation management. The main methods of kākā management include pest control and re-establishments. This thesis evaluated current and past commitments to New Zealand species restoration, as well as an analysis of global Psittacine re-establishment efforts. -

Plant Press, Vol. 18, No. 3

Special Symposium Issue continues on page 12 Department of Botany & the U.S. National Herbarium The Plant Press New Series - Vol. 18 - No. 3 July-September 2015 Botany Profile Seed-Free and Loving It: Symposium Celebrates Pteridology By Gary A. Krupnick ern and lycophyte biology was tee Chair, NMNH) presented the 13th José of this plant group. the focus of the 13th Smithsonian Cuatrecasas Medal in Tropical Botany Moran also spoke about the differ- FBotanical Symposium, held 1–4 to Paulo Günter Windisch (see related ences between pteridophytes and seed June 2015 at the National Museum of story on page 12). This prestigious award plants in aspects of biogeography (ferns Natural History (NMNH) and United is presented annually to a scholar who comprise a higher percentage of the States Botanic Garden (USBG) in has contributed total vascular Washington, DC. Also marking the 12th significantly to flora on islands Symposium of the International Orga- advancing the compared to nization of Plant Biosystematists, and field of tropical continents), titled, “Next Generation Pteridology: An botany. Windisch, hybridization International Conference on Lycophyte a retired profes- and polyploidy & Fern Research,” the meeting featured sor from the Universidade Federal do Rio (ferns have higher rates), and anatomy a plenary session on 1 June, plus three Grande do Sul, was commended for his (some ferns have tree-like growth using additional days of focused scientific talks, extensive contributions to the systematics, root mantle or have internal reinforce- workshops, a poster session, a reception, biogeography, and evolution of neotro- ment by sclerenchyma instead of lateral a dinner, and a field trip. -

IBS 2007 Tenerife Abstract Book

I n t e r n a t i o n a l B i o g e o g r a p h y S o c i e t y Third Biennial Conference, January 9- 13, 2007 Casino Taoro, Puerto de la Cruz Tenerife Canary Islands E xc mo. Ay to. d e P uerto d e la Cruz Third biennial conference of THE INTERNATIONAL BIOGEOGRAPHY SOCIETY an international and interdisciplinary society contributing to the advancement of all studies of the geography of nature Casino Taoro, Puerto de la Cruz January 9-13, 2007 Tenerife, Canary Islands Local Committee Members José María Fernández-Palacios, Rüdiger Otto, Juan Domingo Delgado, Óscar Socas, Tamar de la Concepción, Silvia Fernández Lugo Cover photograph by Rüdiger Otto International Biogeography Society 2005-2007 Officers Secretary - Dov F. Sax Treasurer - Marlis R. Douglas Vice-President for Conferences - Michael Douglas Vice-President for Development & Awards - George Stevens Vice-President for Public Affairs & Communications - Katherine Smith President - Brett R. Riddle; President Elect - Vicki Funk Directors at large - Hector Arita & Robert Whittaker First Past President - James H. Brown Second Past President - Mark V. Lomolino IBS website – www.biogeography.org IBS Mission Statement Biogeography, the study of geography of life, has a long and distinguished history, and one interwoven with that of ecology and evolutionary biology. Traditionally viewed as the study of geographic distributions, modern biogeography now explores a great diversity of patterns in the geographic variation of nature – from physiological, morphological and genetic variation among individulas and populations to differences in the diversity and composition of biotas along geographic gradients. -

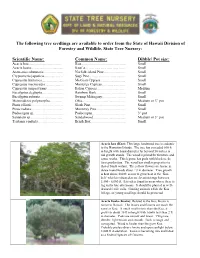

The Following Tree Seedlings Are Available to Order from the State of Hawaii Division of Forestry and Wildlife, State Tree Nursery

The following tree seedlings are available to order from the State of Hawaii Division of Forestry and Wildlife, State Tree Nursery: Scientific Name: Common Name: Dibble/ Pot size: Acacia koa……………………… Koa……………………………….. Small Acacia koaia……………………... Koai’a……………………………. Small Araucaria columnaris…………….. Norfolk-island Pine……………… Small Cryptomeria japonica……………. Sugi Pine………………………… Small Cupressus lusitanica……………... Mexican Cypress………………… Small Cupressus macrocarpa…………… Monterey Cypress……………….. Small Cupressus simpervirens………….. Italian Cypress…………………… Medium Eucalyptus deglupta……………… Rainbow Bark……………………. Small Eucalyptus robusta……………….. Swamp Mahogany……………….. Small Metrosideros polymorpha……….. Ohia……………………………… Medium or 3” pot Pinus elliotii……………………… Slash Pine………………………... Small Pinus radiata……………………... Monterey Pine…………………… Small Podocarpus sp……………………. Podocarpus………………………. 3” pot Santalum sp……………………… Sandalwood……………………… Medium or 3” pot Tristania conferta………………… Brush Box………………………... Small Acacia koa (Koa): This large hardwood tree is endemic to the Hawaiian Islands. The tree has exceeded 100 ft in height with basal diameter far beyond 50 inches in old growth stands. The wood is prized for furniture and canoe works. This legume has pods with black seeds for reproduction. The wood has similar properties to that of black walnut. The yellow flowers are borne in dense round heads about 2@ in diameter. Tree growth is best above 800 ft; seems to grow best in the ‘Koa belt’ which is situated at an elevation range between 3,500 - 6,000 ft. It is often found in areas where there is fog in the late afternoons. It should be planted in well- drained fertile soils. Grazing animals relish the Koa foliage, so young seedlings should be protected Acacia koaia (Koaia): Related to the Koa, Koaia is native to Hawaii. The leaves and flowers are much the same as Koa. -

Achatinella Abbreviata (O`Ahu Tree Snail) 5-Year Review Summary And

Achatinella abbreviata (O`ahu Tree Snail) 5-Year Review Summary and Evaluation U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office Honolulu, Hawai`i 5-YEAR REVIEW Species reviewed: Achatinella abbreviata (O`ahu tree snail) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION.......................................................................................... 3 1.1 Reviewers....................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Methodology used to complete the review:................................................................. 3 1.3 Background: .................................................................................................................. 3 2.0 REVIEW ANALYSIS....................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Application of the 1996 Distinct Population Segment (DPS) policy......................... 4 2.2 Recovery Criteria.......................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Updated Information and Current Species Status .................................................... 6 2.4 Synthesis......................................................................................................................... 9 3.0 RESULTS ........................................................................................................................ 10 3.1 Recommended Classification:................................................................................... -

New Zealand's Threatened Species Strategy

NEW ZEALAND’S THREATENED SPECIES STRATEGY DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION Toitū te marae a Tāne-Mahuta, Toitū te marae a Tangaroa, Toitū te tangata. If the land is well and the sea is well, the people will thrive. From the Minister ew Zealand’s unique While Predator Free 2050 is the single most significant and Nplants, birds, reptiles ambitious conservation programme in our history, it has to and other animal species be part of a broader range of work if we are to succeed. help us to define who we This draft Threatened Species Strategy is the are as a nation. Familiar Government’s plan to halt decline and restore healthy, emblems include our sustainable populations of native species. The Strategy flightless nocturnal kiwi looks at what steps are needed to restore those species and kākāpō, and the at risk of extinction, and what we should do to prevent silver fern proudly worn others from becoming threatened. by our sportspeople and etched on our war graves We are deliberately using the language of war because we and memorials. are up against invasive enemies that are hard to defeat. If we are to save the creatures we love, we have to eradicate They are our national the predators intent on eating them to extinction. taonga, living treasures found nowhere else on Earth – the unique creations of In response to beech tree seeding ‘mast’ years we have millions of years of geographical isolation. launched the successful Battle for our Birds – pest control on a landscape scale. We have declared a War on Weeds The wildlife on our islands of Aotearoa evolved in a with an annual list of the ‘Dirty Dozen’ to tackle invasive world without teeth, a paradise which for all its stunning plants that are suffocating vast areas of our bush. -

The Threat of the Non-Native Neotropical Rust Puccinia Psidii to Hawaiian Biodiversity and Native Ecosystems: a Case Example of the Need for Prevention

The Threat of the Non-native Neotropical Rust Puccinia psidii to Hawaiian Biodiversity and Native Ecosystems: A Case Example of the Need for Prevention Lloyd Loope, U.S. Geological Survey,Pacific Island Ecosystems Research Center, Haleaka- la Field Station, P.O. Box 369, Makawao, HI 96768; [email protected] Janice Uchida, Department of Plant and Environmental Protection Sciences, University of Hawaii at Manoa, 3190 Maile Way, Honolulu, HI 96822; [email protected] Loyal Mehrhoff, U.S. Geological Survey, Pacific Island Ecosystems Research Center, 677 Ala Moana Boulevard, Suite 615, Honolulu, HI 96813; [email protected] Introduction The threat of invasive species to natural areas presents enormous challenges, but there are opportunities for working toward solutions, often in conjunction with agricultural and forestry perspectives. There is a growing awareness of the danger to botanical biodiversity and conservation from “emerging infectious diseases” that have increased in incidence, geo- graphical distribution, or host range/pathogenicity; have newly evolved characteristics; and/or have been newly discovered (Anderson et al. 2004). There is a heightened concern for forest health due to accelerating worldwide movement of plant pathogens (e.g., with inef- fective quarantine measures) that negatively affect both biodiversity and commercial forestry (Wingfield 2003). An important related concept is that of the ability of fungi to jump to new hosts following anthropogenic introduction. Native hosts are exposed to pathogens with no coevolved recognition or defense mechanism, and microevolution toward increased viru- lence of introduced pathogens can result (Wingfield 2003; Slippers et al. 2005). The rust fungus Puccinia psidii (Basidiomycota, Uredinales: Pucciniaceae), a species first document- ed to have jumped from native guava (Psidium guajava, Myrtaceae) to introduced Eucalyp- tus spp. -

Myrtle Rust Reviewed the Impacts of the Invasive Plant Pathogen Austropuccinia Psidii on the Australian Environment R

Myrtle Rust reviewed The impacts of the invasive plant pathogen Austropuccinia psidii on the Australian environment R. O. Makinson 2018 DRAFT CRCPLANTbiosecurity CRCPLANTbiosecurity © Plant Biosecurity Cooperative Research Centre, 2018 ‘Myrtle Rust reviewed: the impacts of the invasive pathogen Austropuccinia psidii on the Australian environment’ is licenced by the Plant Biosecurity Cooperative Research Centre for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Australia licence. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ This Review provides background for the public consultation document ‘Myrtle Rust in Australia – a draft Action Plan’ available at www.apbsf.org.au Author contact details R.O. Makinson1,2 [email protected] 1Bob Makinson Consulting ABN 67 656 298 911 2The Australian Network for Plant Conservation Inc. Cite this publication as: Makinson RO (2018) Myrtle Rust reviewed: the impacts of the invasive pathogen Austropuccinia psidii on the Australian environment. Plant Biosecurity Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra. Front cover: Top: Spotted Gum (Corymbia maculata) infected with Myrtle Rust in glasshouse screening program, Geoff Pegg. Bottom: Melaleuca quinquenervia infected with Myrtle Rust, north-east NSW, Peter Entwistle This project was jointly funded through the Plant Biosecurity Cooperative Research Centre and the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program. The Plant Biosecurity CRC is established and supported under the Australian Government Cooperative Research Centres Program. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This review of the environmental impacts of Myrtle Rust in Australia is accompanied by an adjunct document, Myrtle Rust in Australia – a draft Action Plan. The Action Plan was developed in 2018 in consultation with experts, stakeholders and the public. The intent of the draft Action Plan is to provide a guiding framework for a specifically environmental dimension to Australia’s response to Myrtle Rust – that is, the conservation of native biodiversity at risk. -

Hawaiian Hoary Bat Inventory in National Parks on Hawaii, Maui and Molokai

PACIFIC COOPERATIVE STUDIES UNIT UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI`I AT MĀNOA Dr. David C. Duffy, Unit Leader Department of Botany 3190 Maile Way, St. John #408 Honolulu, Hawai’i 96822 Technical Report 140 HAWAIIAN HOARY BAT INVENTORY IN NATIONAL PARKS ON HAWAI`I, MAUI AND MOLOKA`I April 2007 Heather R. Fraser1 Vanessa Parker-Geisman1 George R. Parish, IV1 1. Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit (University of Hawai`i at Mānoa), NPS Inventory and Monitoring Program, Pacific Island Network, PO Box 52, Hawai`i National Park, HI 96718 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................iii List of Figures ....................................................................................................iii Abstract ...............................................................................................................1 Introduction.........................................................................................................2 Methods ...............................................................................................................3 Study Area .....................................................................................................3 Selection of Survey Points and Transects .....................................................5 Survey Methods.............................................................................................8 Results...............................................................................................................10 -

A Parrot Apart: the Natural History of the Kakapo (Strigops Habroptilus), and the Context of Its Conservation Management

A parrot apart: the natural history of the kakapo (Strigops habroptilus), and the context of its conservation management RALPH G. POWLESLAND Abstract Since the last review of kakapo biology, published 50 years ago, much Research, Development & Improvement has been learnt as a result of the transfer of all known individuals to offshore islands, Division, Department of Conservation, P.O. and their intensive management to increase adult survival and productivity. This Box 10-420, Wellington, New Zealand review summarises information on a diversity of topics, including taxonomy, plumage, [email protected] moult, mass, anatomy, physiology, reasons for decline in distribution, present numbers and status, sex ratio, habitat, home range, foraging activities, diet, voice, DON V. MERTON breeding biology, nesting success, sexual maturity, and adult survival. In addition, Honorary Research Associate, Research, those kakapo attributes that compromise its long-term survival in present-day New Development & Improvement Division, Zealand are discussed, along with management practises developed to overcome Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10- these problems. 420, Wellington, New Zealand Powlesland, R.G.; Merton, D.V.; Cockrem, J.F. 2006. A parrot apart: the natural JOHN F. COCKREM history of the kakapo (Strigops habroptilus), and the context of its conservation Conservation Endocrinology Research management. Notornis 53 (1): 3 - 26. Group, Institute of Veterinary, Animal & Biomedical Sciences, Massey University, Keywords Kakapo; Strigops habroptilus; Psittacidae; endangered species; review; Private Bag 11-222, Palmerston North, natural history; management practices; predatory mammals New Zealand INTRODUCTION The kakapo (Strigops habroptilus) is a large parrot (males 1.6 – 3.6 kg, females 0.9 – 1.9 kg) (Higgins 1999), with finely barred or mottled yellowish-green plumage.