Out of Sight – out of Mind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangladesh Workplace Death Report 2020

Bangladesh Workplace Death Report 2020 Supported by Published by I Bangladesh Workplace Death Report 2020 Published by Safety and Rights Society 6/5A, Rang Srabonti, Sir Sayed Road (1st floor), Block-A Mohammadpur, Dhaka-1207 Bangladesh +88-02-9119903, +88-02-9119904 +880-1711-780017, +88-01974-666890 [email protected] safetyandrights.org Date of Publication April 2021 Copyright Safety and Rights Society ISBN: Printed by Chowdhury Printers and Supply 48/A/1 Badda Nagar, B.D.R Gate-1 Pilkhana, Dhaka-1205 II Foreword It is not new for SRS to publish this report, as it has been publishing this sort of report from 2009, but the new circumstances has arisen in 2020 when the COVID 19 attacked the country in March . Almost all the workplaces were shut about for 66 days from 26 March 2020. As a result, the number of workplace deaths is little bit low than previous year 2019, but not that much low as it is supposed to be. Every year Safety and Rights Society (SRS) is monitoring newspaper for collecting and preserving information on workplace accidents and the number of victims of those accidents and publish a report after conducting the yearly survey – this year report is the tenth in the series. SRS depends not only the newspapers as the source for information but it also accumulated some information from online media and through personal contact with workers representative organizations. This year 26 newspapers (15 national and 11 regional) were monitored and the present report includes information on workplace deaths (as well as injuries that took place in the same incident that resulted in the deaths) throughout 2020. -

BANGABANDHU SHEIKH MUJIB SHILPANAGAR Mirsarai-Sitakundu-Sonagazi Chattogram-Feni

BANGABANDHU SHEIKH MUJIB SHILPANAGAR Mirsarai-Sitakundu-Sonagazi Chattogram-Feni Bangladesh Economic Zones Authority (BEZA) BANGABANDHU SHEIKH MUJIB SHILPANAGAR EDITORIAL BOARD Paban Chowdhury, Executive Chairman, BEZA Md. Harunur Rashid, Executive Member, BEZA Mohammad Hasan Arif, General Manager, BEZA Shenjuti Barua, Deputy Manager, BEZA Md. Abdul Quader Khan, Social Consultant, BEZA PUBLISHED IN May 2020 PUBLISHER Bangladesh Economic Zones Authority (BEZA) Prime Minister’s Office DESIGN AND PRINTING Nymphea Publication © Bangladesh Economic Zones Authority (BEZA) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying recording or otherwise without prior permission of the publisher. The book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover, other than that in which it is published. 4 Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Shilpanagar gyw³i msMªv‡gi †P‡qI †`k Movi msMÖvg KwVb, ZvB †`k Movi Kv‡R Avgv‡`i me©kw³ wb‡qvM Ki‡Z n‡e - e½eÜz †kL gywReyi ingvb PRIME MINISTER Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh 10 Falgun 1426 MESSAGE 23 February 2020 I am happy to know that Bangladesh Economic Zones Authority (BEZA) is the establishment of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Shilpanagar (BSMSN) publishing a book on the development scenario of Bangabandhu Shekih comprising Mirsarai, Feni and Sitakunda Economic Zones, on 30,000 Mujib Shilpanagar (BSMSN) covering some excellent accomplishments acres of land has created a hilarious prospect among the local and experienced so far. -

Arsenic Incorporation Into Garden Vegetables Irrigated with Contaminated Water

JASEM ISSN 1119-8362 Full-text Available Online at J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manage. December, 2007 All rights reserved www.bioline.org.br/ja Vol. 11(4) 105 - 112 Arsenic Incorporation into Garden Vegetables Irrigated with Contaminated Water RAHMAN I.M.M. * AND HASAN M.T. Applied Research Laboratory, Department of Chemistry, University of Chittagong, Chittagong-4331, Bangladesh *Corresponding Author. Tel.: +88-031-635631. Fax: +88-031-726310. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Daily vegetable requirement are mostly fulfilled in Bangladesh through homestead garden production which are usually irrigated with arsenic-rich underground water. Garden vegetables grown in arsenic-tainted soil may uptake and accumulate significant amount of arsenic in their tissue. Mean, minimum and maximum arsenic content in some common garden vegetables, e.g. bean, bitter gourd, bottle gourd, brinjal, chilli, green papaya, mint, okra, palwal, potato, red amaranth, string bean and sweet gourd, from an arsenic- prone locality of Bangladesh have been assessed. The contribution of vegetable-arsenic in the daily diet was estimated. Correlation with the groundwater arsenic status and statistical significance of variations has been discussed. @ JASEM The natural contamination of shallow hand extracted from the shallow tubewells, were tubewells in Bangladesh with arsenic has caused collected in pre-washed polyethylene bottles. widespread human exposure to this toxic element 0.01% HNO3 per litre of water was added as through drinking water (Karim, 2000, Paul et al., preservative and kept at 4°C before analysis. Ag- 2000). Beside direct consumption for drinking, DDTC-Hexamethylenetetramine-Chloroform arsenic contaminated water is also used for method, having detection limit 0.20 µg/mL of irrigation and cooking purposes. -

Bounced Back List.Xlsx

SL Cycle Name Beneficiary Name Bank Name Branch Name Upazila District Division Reason for Bounce Back 1 Jan/21-Jan/21 REHENA BEGUM SONALI BANK LTD. NA Bagerhat Sadar Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 23-FEB-21-R03-No Account/Unable to Locate Account 2 Jan/21-Jan/21 ABDUR RAHAMAN SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number SHEIKH 3 Jan/21-Jan/21 KAZI MOKTADIR HOSEN SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 4 Jan/21-Jan/21 BADSHA MIA SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 5 Jan/21-Jan/21 MADHAB CHANDRA SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number SINGHA 6 Jan/21-Jan/21 ABDUL ALI UKIL SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 7 Jan/21-Jan/21 MRIDULA BISWAS SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 8 Jan/21-Jan/21 MD NASU SHEIKH SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 9 Jan/21-Jan/21 OZIHA PARVIN SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 10 Jan/21-Jan/21 KAZI MOHASHIN SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 11 Jan/21-Jan/21 FAHAM UDDIN SHEIKH SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 12 Jan/21-Jan/21 JAFAR SHEIKH SONALI BANK LTD. -

Sitakunda Upazila Chittagong District Bangladesh

Integrated SMART Survey Nutrition, Care Practices, Food Security and Livelihoods, Water Sanitation and Hygiene Sitakunda Upazila Chittagong District Bangladesh January 2018 Funded By Acknowledgement Action Against Hunger conducted Baseline Integrated SMART Nutrition survey in Sitakunda Upazila in collaboration with Institute of Public Health Nutrition (IPHN). Action Against Hunger would like to acknowledge and express great appreciation to the following organizations, communities and individuals for their contribution and support to carry out SMART survey: District Civil Surgeon and Upazila Health and Family Planning Officer for their assistance for successful implementation of the survey in Sitakunda Upazila. Action Against Hunger-France for provision of emergency response funding to implement the Integrated SMART survey as well as technical support. Leonie Toroitich-van Mil, Health and Nutrition Head of department of Action Against Hunger- Bangladesh for her technical support. Mohammad Lalan Miah, Survey Manager for executing the survey, developing the survey protocol, providing training, guidance and support to the survey teams as well as the data analysis and writing the final survey report. Action Against Hunger Cox’s Bazar for their logistical support and survey financial management. Mothers, Fathers, Caregivers and children who took part in the assessment during data collection. Action Against Hunger would like to acknowledge the community representatives and community people who have actively participated in the survey process for successful completion of the survey. Finally, Action Against Hunger is thankful to all of the surveyors, supervisor and Survey Manager for their tremendous efforts to successfully complete the survey in Sitakunda Upazila. Statement on Copyright © Action Against Hunger | Action Contre la Faim Action Against Hunger (ACF) is a non-governmental, non-political and non-religious organization. -

Tor for Preparation of Development Plan for Mirsharai Upazila, Chittagong District: Risk Sensitive Landuse Plan

Selection of Web Firm for Web Site Designing Development & Hosting ToR for Preparation of Development Plan for Mirsharai Upazila, Chittagong District: Risk Sensitive Landuse Plan ANNEX-X TERMS OF REFERENCE (TOR) for Selection of Web Firm for Web Site Designing Development & Hosting Under ÒPÆMÖvg †Rjvi gximivB Dc‡Rjvi Dbœqb cwiKíbv cÖYqb t mvwe©K `y‡h©vM e¨e¯’vcbv‡K f~wg e¨env‡ii gva¨‡g m¤ú„³KiYÓ (Preparation of Development Plan for Mirsharai Upazila, Chattogram District: Risk Sensitive Landuse Plan) URBAN DEVELOPMENT DIRECTORATE Ministry of Housing and Public Works Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh November, 2016 Signature of the Bidder Signature of the Project Director Signature of the Director 131 Selection of Web Firm for Web Site Designing Development & Hosting ToR for Preparation of Development Plan for Mirsharai Upazila, Chittagong District: Risk Sensitive Landuse Plan Table of Content Content Page No. Appendix-01: Background Information of the Project 133 Appendix-02: Scope of Work of the Assignment 136 Appendix-03: Bidding For Tender 141 Appendix-04: Format of Curriculum Vitae and Project Team 142 Signature of the Bidder Signature of the Project Director Signature of the Director 132 Selection of Web Firm for Web Site Designing Development & Hosting ToR for Preparation of Development Plan for Mirsharai Upazila, Chittagong District: Risk Sensitive Landuse Plan APPENDIX 01 BCKGROUND INFORMATION OF THE PROJECT 1.1. Project Background Mirsharai Upazila (CHATTOGRAM DISTRICT) area 482.88 sqkm(BBS)/509.80sqkm(GIS Data), located in between 22°39' and 22°59' north latitudes and in between 91°27' and 91°39' east longitudes. -

Diversity of Cropping Systems in Chittagong Region

Bangladesh Rice J. 21 (2) : 109-122, 2017 Diversity of Cropping Systems in Chittagong Region S M Shahidullah1*, M Nasim1, M K Quais1 and A Saha1 ABSTRACT The study was conducted over all 42 upazilas of Chittagong region during 2016 using pre-tested semi- structured questionnaire with a view to document the existing cropping patterns, cropping intensity and crop diversity in the region. The most dominant cropping pattern Boro−Fallow−T. Aman occupied about 23% of net cropped area (NCA) of the region with its distribution over 38 upazilas out 42. The second largest area, 19% of NCA, was covered by single T. Aman, which was spread out over 32 upazilas. A total of 93 cropping patterns were identified in the whole region under the present investigation. The highest number of cropping patterns was 28 in Naokhali sadar and the lowest was 4 in Begumganj of the same district. The lowest crop diversity index (CDI) was observed 0.135 in Chatkhil followed by 0.269 in Begumganj. The highest value of CDI was observed in Banshkhali, Chittagong and Noakhali sadar (around 0.95). The range of cropping intensity values was recorded 103−283%. The maximum value was for Kamalnagar upazila of Lakshmipur district and minimum for Chatkhil upazila of Noakhali district. As a whole the CDI of Chittagong region was 0.952 and the average cropping intensity at the regional level was 191%. Key words: Crop diversity index, land use, cropping system, soybean, and soil salinity INTRODUCTION household enterprises and the physical, biological, technological and socioeconomic The Chittagong region consists of five districts factors or environments. -

Assessing Energy-Based CO2 Emission and Workers' Health

environments Article Assessing Energy-Based CO2 Emission and Workers’ Health Risks at the Shipbreaking Industries in Bangladesh Nandita Mitra 1, Shihab Ahmad Shahriar 1 , Nurunnaher Lovely 2, Md Shohel Khan 1, Aweng Eh Rak 3, S. P. Kar 4, Md Abdul Khaleque 5, Mohamad Faiz Mohd Amin 3, Imrul Kayes 1 and Mohammed Abdus Salam 1,* 1 Department of Environment Science and Disaster Management, Noakhali Science and Technology University, Noakhali 3814, Bangladesh; [email protected] (N.M.); [email protected] (S.A.S.); [email protected] (M.S.K.); [email protected] (I.K.) 2 Department of Chemistry, South Banasree Model High School and College, Dhaka 1219, Bangladesh; [email protected] 3 Faculty of Earth Science, University Malaysia Kelantan, Jeli 17600, Malaysia; [email protected] (A.E.R.); [email protected] (M.F.M.A.) 4 College of Natural Resources, University of Wisconsin, Stevens Point, WI 54481, USA; [email protected] 5 Department of Environmental Science, School of Environmental Science and Management, Independent University Bangladesh, Dhaka 1219, Bangladesh; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +880-191-763-5348 Received: 2 March 2020; Accepted: 26 April 2020; Published: 30 April 2020 Abstract: The study represents the estimation of energy-based CO2 emission and the health risks of workers involved in the shipbreaking industries in Sitakunda, Bangladesh. To calculate the carbon emission (CE) from three shipbreaking activities, i.e., metal gas cutting (GC), diesel fuel (FU) and electricity consumption (EC), we used the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) guidelines and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s Emission and Generation Resource Integrated Database (eGRID) emission factors. -

List of Upazilas of Bangladesh

List Of Upazilas of Bangladesh : Division District Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Akkelpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Joypurhat Sadar Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Kalai Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Khetlal Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Panchbibi Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Adamdighi Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Bogra Sadar Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Dhunat Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Dhupchanchia Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Gabtali Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Kahaloo Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Nandigram Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Sariakandi Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Shajahanpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Sherpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Shibganj Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Sonatola Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Atrai Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Badalgachhi Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Manda Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Dhamoirhat Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Mohadevpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Naogaon Sadar Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Niamatpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Patnitala Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Porsha Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Raninagar Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Sapahar Upazila Rajshahi Division Natore District Bagatipara -

Chittagong C09.Pdf

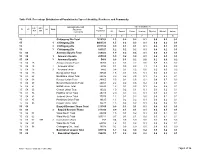

Table C-09: Percentage Distribution of Population by Type of disability, Residence and Community Administrative Unit Type of disability (%) UN / MZ / Total ZL UZ Vill RMO Residence WA MH Population Community All Speech Vision Hearing Physical Mental Autism 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 15 Chittagong Zila Total 7616352 1.3 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.5 0.2 0.1 15 1 Chittagong Zila 4463723 1.5 0.2 0.3 0.1 0.6 0.2 0.1 15 2 Chittagong Zila 2971102 0.9 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.4 0.1 0.1 15 3 Chittagong Zila 181527 1.2 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.4 0.2 0.1 15 04 Anowara Upazila Total 259022 1.9 0.2 0.4 0.1 0.8 0.3 0.1 15 04 1 Anowara Upazila 253556 1.9 0.2 0.4 0.1 0.8 0.3 0.1 15 04 3 Anowara Upazila 5466 0.8 0.1 0.2 0.0 0.2 0.0 0.2 15 04 15 Anowara Union Total 10260 4.2 0.3 2.2 0.6 0.8 0.2 0.2 15 04 15 1 Anowara Union 4794 8.1 0.5 4.5 1.1 1.5 0.3 0.3 15 04 15 3 Anowara Union 5466 0.8 0.1 0.2 0.0 0.2 0.0 0.2 15 04 19 Bairag Union Total 30545 1.8 0.1 0.5 0.1 0.6 0.3 0.1 15 04 28 Barakhain Union Total 28836 3.0 0.2 0.5 0.1 1.8 0.3 0.1 15 04 38 Barasat Union Total 28865 2.5 0.2 0.6 0.2 0.8 0.7 0.2 15 04 47 Burumchhara Union Total 20061 2.2 0.2 0.6 0.2 1.0 0.1 0.1 15 04 57 Battali Union Total 23630 1.3 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.5 0.2 0.1 15 04 66 Chatari Union Total 19022 1.0 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 0.1 15 04 76 Haildhar Union Total 25315 2.0 0.4 0.3 0.1 0.7 0.3 0.1 15 04 81 Juidandi Union Total 17575 1.2 0.1 0.2 0.0 0.6 0.1 0.1 15 04 85 Paraikora Union Total 19635 1.3 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.6 0.2 0.1 15 04 95 Roypur Union Total 35278 1.5 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.6 0.2 0.1 15 06 Bayejid Bostami Thana Total 211355 0.9 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.4 0.1 0.1 15 06 2 Bayejid Bostami Thana 211355 0.9 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.4 0.1 0.1 15 06 01 Ward No-01 Total 29209 1.5 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.9 0.1 0.1 15 06 02 Ward No-02 Total 103314 0.7 0.1 0.1 0.0 0.3 0.1 0.1 15 06 02 998 2 Cantonment (Part) 758 0.4 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.1 0.0 0.3 15 06 03 Ward No-03 Total 68794 1.2 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.5 0.2 0.1 15 06 98 Chittagang Cnt. -

Researched and Compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 7 April 2015

Bangladesh – Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 7 April 2015 Information on Islami Chhatra Shibir including: General information; Treatment of members by Awami League post election in January 2014, particularly Chittagong and Sylhet divisions; State/police protection; Treatment of returning members. A document published by the South Asia Terrorism Portal refers to Islami Chhatra Shibir as follows: “The Islami Chhatra Shibir is the student wing of the Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh, which came into existence in 1941.” (South Asia Terrorism Portal (undated) Islami Chhatra Shibir (ICS)) In a paragraph headed “Objective” this document states: “According to the outfit, its objectives are to struggle for changing the existing system of education on the basis of Islamic values, to inspire students to acquire Islamic knowledge and to prepare them to take part in the struggle for establishing Islamic way of life. A significant aim of the outfit is to establish an Afghanistan-Taliban type Islamist regime in Bangladesh. Consequently, the outfit is opposed to forces of modernization, secularism and democracy.” (ibid) See also paragraph headed “External Linkages” which states: “As one of the largest Islamist student organisations in South Asia, the ICS maintains a close relationship with various Islamist fundamentalist organisations of different countries. In 1979, the ICS secured membership of International Islamic Federation of Student Organisation (IIFSO). Its former President Dr. S A M Taher was also the Secretary General of IIFSO. The outfit is also a member of the World Assembly of Muslim Youth (WAMY). The outfit is also reported to be maintaining close links with the Inter Services Intelligence (ISI), Pakistan’s external intelligence agency. -

Anticipated Environmental Impacts And

Public Disclosure Authorized GOVERNMENT OF THE PEOPLES' REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH MINISTRY OF FOOD DIRECTORATE GENERAL OF FOOD MODERN FOOD STORAGE FACILITIES PROJECT (MFSP) IDA Credit # 5265-BD ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) REPORT FOR THE CONSTRUCTION OF GALVANIZED CORRUGATED FLAT BOTTOM STEEL SILO WITH RCC FOUNDATION AND IT'S ANCILLARY WORKS AT Public Disclosure Authorized CHATTOGRAM SILO SITE Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT DIRECTOR MODERN FOOD STORAGE FACILITIES PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized PROBASHI KALLAYAN BHABAN, 71-72, ESKATON GARDEN RAMNA, DHAKA-1000, BANGLADESH. OCTOBER, 2019 Modern Food Storage Facilities Project (MFSP), Chattogram Table of Contents ACRONYMS & ABBREVIATIONS...................................................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... ix 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Background ................................................................................................................. 1 1.2. Objectives of the Project ............................................................................................. 2 1.2.1 Strategic Objectives ............................................................................................. 2 1.2.2 Specific Objectives .............................................................................................