Emunat Itecha 124 English Pages Tammuz 5779

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rosh Hashanah Jewish New Year

ROSH HASHANAH JEWISH NEW YEAR “The LORD spoke to Moses, saying: Speak to the Israelite people thus: In the seventh month, on the first day of the month, you shall observe complete rest, a sacred occasion commemorated with loud blasts. You shall not work at your occupations; and you shall bring an offering by fire to the LORD.” (Lev. 23:23-25) ROSH HASHANAH, the first day of the seventh month (the month of Tishri), is celebrated as “New Year’s Day”. On that day the Jewish people wish one another Shanah Tovah, Happy New Year. ש נ ָׁהָׁטוֹב ָׁה Rosh HaShanah, however, is more than a celebration of a new calendar year; it is a new year for Sabbatical years, a new year for Jubilee years, and a new year for tithing vegetables. Rosh HaShanah is the BIRTHDAY OF THE WORLD, the anniversary of creation—a fourfold event… DAY OF SHOFAR BLOWING NEW YEAR’S DAY One of the special features of the Rosh HaShanah prayer [ רֹאשָׁהַש נה] Rosh HaShanah THE DAY OF SHOFAR BLOWING services is the sounding of the shofar (the ram’s horn). The shofar, first heard at Sinai is [זִכְּ רוֹןָׁתְּ רּועה|יוֹםָׁתְּ רּועה] Zikaron Teruah|Yom Teruah THE DAY OF JUDGMENT heard again as a sign of the .coming redemption [יוֹםָׁהַדִ ין] Yom HaDin THE DAY OF REMEMBRANCE THE DAY OF JUDGMENT It is believed that on Rosh [יוֹםָׁהַזִכְּ רוֹן] Yom HaZikaron HaShanah that the destiny of 1 all humankind is recorded in ‘the Book of Life’… “…On Rosh HaShanah it is written, and on Yom Kippur it is sealed, how many will leave this world and how many will be born into it, who will live and who will die.. -

Chanukah at Home Booklet

MJCS CHANUKAH @HOME “The proper response, as Chanukah teaches, is not to curse the darkness but to light a candle.” —Rabbi Irving Greenberg We’ve come to dispel the darkness. In our hands are light and fire. Each one of us is a small light, but all of us [together] are a strong beacon! Flee darkness! Retreat night! Flee because of the light! —Popular Hebrew Chanukah children’s song Each Jewish holiday has its unique rituals, tastes, songs, and experiences. Many of us associate Chanukah with the hopeful and warm glow of lighting candles at home, tasting latkes, and spinning dreidels! This year particularly, Chanukah will be a holiday we experience at home. MJCS has put together this at- home holiday guidebook to help you make this Chanukah at home an especially cheerful and celebratory holiday full of light, spirit, and joy! A Short History of Chanukah Chanukah is one of just a few Jewish holidays that are not mentioned in the Tanach, the Hebrew Bible. Chanukah recalls how Jewish freedom fighters liberated our ancestors from oppression. Under the Seleucid (Syrian-Greek) Empire’s ruler, Antiochus IV Epiphanes, efforts to impose Hellenist culture in the land of Israel intensified by 167 BCE with an order to end all Jewish practice and the defilement of the Temple in Jerusalem. Led by the priest Mattathias and his five sons from the village of Modi’in, including Judah who was a brilliant strategist, the Maccabees revolted and waged a guerilla war against the stronger and better equipped Seleucid army. After three years of battle, the Maccabees prevailed and rededicated the Temple beginning on the 25th of Kislev in 164BCE. -

Hafrashas Challah and Women 1. the Mitzvah of Separating Challah Is

Hafrashas Challah and Women 1. The mitzvah of separating Challah is one of the three mitzvos which are uniquely given over to women to perform. The other two are (1) lighting the Shabbos candles and (2) Taharas Hamishpacha. 2. It is also a merit for women who perform these mitzvos carefully, to have a safe childbirth. 3. The medrash tells us that when Sarah Imeinu was niftar, three special things no longer existed. These three are the cloud that hovered over her tent, that her candles stayed lit from week to week and that her challah remained fresh all week long. The three parallel the three mitzvos that are uniquely women’s. 4. One who separates challah, is considered as if he had nullified idol worship, since: a. She is making the statement that all material blessings come from H-shem and that it is H-shem who grants us material wealth. b. She recognizes the source of everything and the unity in Creation and that even mundane acts are connected to spirituality. We are both body and soul - the two are connected. Food connects our body and soul – without food, one cannot live and one’s soul leaves the body. c. Furthermore, food affects our neshama. H-shem created every being with a food which is appropriate for it. Human beings have food which requires labor – bread is not picked off a tree; there are many steps which are required (and listed in the laws of Shabbos) until the bread is complete. It represents that which man can exist from. -

Pesachim 038.Pub

כ"א אב תשע“ג Sunday, July 28, 2013 פסחים ל“ח בס“ד ישראל צבי בן זאב גוטליב ז"ל Daf Digest for this month is dedicated in memory of By the Weiss/Gotlib Families—London,by England OVERVIEW of the Daf Distinctive INSIGHT 1) Ma’aser Sheni The loaves of Todah are disqualified for the mitzvah of R’ Assi identifies three applications (challah, matzah matzah רב יוסף אמר: אמר קרא שבעת ימים מצות תאכלו מצה הנאכלת and esrog) of the disagreement between R’ Meir and לשבעת ימים יצתה זו שאינה נאכלת אלא ליום ולילה Chachamim, regarding the question of whether ma’aser sheni belongs to the person himself or Hashem, he Gemara provides several opinions to explain the After a failed challenge to R’ Assi’s statement the T law of the Mishnah that the loaves of a Todah offering Gemara suggests, unsuccessfully, a proof for his asser- cannot be used to fulfill the mitzvah of eating matzah. Rav tion from a Baraisa. Yosef cites the verse which tells us that the matzah is some- Reish Lakish asked whether, according to R’ Akiva, thing that is eaten for seven days—the entire duration of a person could fulfill his matzah obligation with challah the holiday of Pesach. The loaves of a Todah offering made from ma’aser sheni grain. (those that are matzah and not chometz) can only be eaten According to a second version, Reish Lakish in- for a day and night following the slaughter of the animal quired, according to R’ Yehudah, whether a person which is brought as the offering itself. -

Shabbos Secrets - the Mysteries Revealed

Translated by Rabbi Awaharn Yaakov Finkel Shabbos Secrets - The Mysteries Revealed First Published 2003 Copyright O 2003 by Rabbi Dovid D. Meisels ISBN: 1-931681-43-0 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be translated, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in an form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording, or otherwise, withour prior permission in writing from both the copyright holder and publisher. C<p.?< , . P*. P,' . , 8% . 3: ,. ""' * - ;., Distributed by: Isreal Book Shop -WaUvtpttrnn 501 Prospect Street w"Jw--.or@r"wn owwv Lakewood NJ 08701 Tel: (732) 901-3009 Fax: (732) 901-4012 Email: isrbkshp @ aol.com Printed in the United States of America by: Gross Brothers Printing Co., Inc. 3 125 Summit Ave., Union City N.J. 07087 This book is dedicated to be a source of merit in restoring the health and in strengthening 71 Tsn 5s 3.17 ~~w7 May Hashem send him from heaven a speedy and complete recovery of spirit and body among the other sick people of Israel. "May the Zechus of Shabbos obviate the need to cry out and may the recovery come immediately. " His parents should inerit to have much nachas from him and from the entire family. I wish to express my gratitude to Reb Avraham Yaakov Finkel, the well-known author and translator of numerous books on Torah themes, for his highly professional and meticulous translation from the Yiddish into lucid, conversational English. The original Yiddish text was published under the title Otzar Hashabbos. My special appreciation to Mrs. -

Jewish Law Research Guide

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Library Research Guides - Archived Library 2015 Jewish Law Research Guide Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides Part of the Religion Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Repository Citation Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library, "Jewish Law Research Guide" (2015). Law Library Research Guides - Archived. 43. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides/43 This Web Page is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Library Research Guides - Archived by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Home - Jewish Law Resource Guide - LibGuides at C|M|LAW Library http://s3.amazonaws.com/libapps/sites/1185/guides/190548/backups/gui... C|M|LAW Library / LibGuides / Jewish Law Resource Guide / Home Enter Search Words Search Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life. Home Primary Sources Secondary Sources Journals & Articles Citations Research Strategies Glossary E-Reserves Home What is Jewish Law? Need Help? Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Halakha from the Hebrew word Halakh, Contact a Law Librarian: which means "to walk" or "to go;" thus a literal translation does not yield "law," but rather [email protected] "the way to go". Phone (Voice):216-687-6877 Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and Text messages only: ostensibly non-religious life 216-539-3331 Jewish religious tradition does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities. -

New Contradictions Between the Oral Law and the Written Torah 222

5/7/2019 222 New Contradictions between the Oral Torah and the Written Torah - iGod.co.il Science and faith main New Contradictions Between The Oral Law And The Written Torah 222 Contradictions in the Oral Law Talmud Mishneh Halacha 1/68 /מדע-אמונה/-101סתירות-מביכות-בין-התורה-שבעל-פה-לתורה/https://igod.co.il 5/7/2019 222 New Contradictions between the Oral Torah and the Written Torah - iGod.co.il You may be surprised to hear this - but the concept of "Oral Law" does not appear anywhere in the Bible! In truth, such a "Oral Law" is not mentioned at all by any of the prophets, kings, or writers in the entire Bible. Nevertheless, the Rabbis believe that Moses was given the Oral Torah at Sinai, which gives them the power, authority and control over the people of Israel. For example, Rabbi Shlomo Ben Eliyahu writes, "All the interpretations we interpret were given to Moses at Sinai." They believe that the Oral Torah is "the words of the living God". Therefore, we should expect that there will be no contradictions between the written Torah and the Oral Torah, if such was truly given by God. But there are indeed thousands of contradictions between the Talmud ("the Oral Law") and the Bible (Torah Nevi'im Ketuvim). According to this, it is not possible that Rabbinic law is from God. The following is a shortened list of 222 contradictions that have been resurrected from the depths of the ocean of Rabbinic literature. (In addition - see a list of very .( embarrassing contradictions between the Talmud and science . -

URJ Online Communications Master Word List 1 MASTER

URJ Online Communications Master Word List MASTER WORD LIST, Ashamnu (prayer) REFORMJUDAISM.org Ashkenazi, Ashkenazim Revised 02-12-15 Ashkenazic Ashrei (prayer) Acharei Mot (parashah) atzei chayim acknowledgment atzeret Adar (month) aufruf Adar I (month) Av (month) Adar II (month) Avadim (tractate) “Adir Hu” (song) avanah Adon Olam aveirah Adonai Avinu Malkeinu (prayer) Adonai Melech Avinu shebashamayim Adonai Tz’vaot (the God of heaven’s hosts [Rev. avodah Plaut translation] Avodah Zarah (tractate) afikoman avon aggadah, aggadot Avot (tractate) aggadic Avot D’Rabbi Natan (tractate) agunah Avot V’Imahot (prayer) ahavah ayin (letter) Ahavah Rabbah (prayer) Ahavat Olam (prayer) baal korei Akeidah Baal Shem Tov Akiva baal t’shuvah Al Cheit (prayer) Babylonian Empire aleph (letter) Babylonian exile alef-bet Babylonian Talmud Aleinu (prayer) baby naming, baby-naming ceremony Al HaNisim (prayer) badchan aliyah, aliyot Balak (parashah) A.M. (SMALL CAPS) bal tashchit am baraita, baraitot Amidah Bar’chu Amora, Amoraim bareich amoraic Bar Kochba am s’gulah bar mitzvah Am Yisrael Baruch atah Adonai, Eloheinu Melech haolam, Angel of Death asher kid’shanu b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu Ani Maamin (prayer) Baruch She-Amar (prayer) aninut Baruch Shem anti-Semitism Baruch SheNatan (prayer) Arachin (tractate) bashert, basherte aravah bat arbaah minim bat mitzvah arba kanfot Bava Batra (tractate) Arba Parashiyot Bava Kama (tractate) ark (synagogue) Bava M’tzia (tractate) ark (Noah’s) Bavli Ark of the Covenant, the Ark bayit (house) Aron HaB’rit Bayit (the Temple) -

Volume 4 Issue 5

Halachically Speaking Volume 4 Issue 5 Compiled by Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits Reviewed by Rabbi Benzion Schiffenbauer Shlita Preparing for Shabbos Part 2 All Piskei Horav Yisroel Belsky Shlita are reviewed by Horav Yisroel Belsky Shlita Traveling on Erev Shabbos time, when in fact it is not and may come to 6 Traffic is something that one can never really chillul Shabbos . be sure about beforehand. Therefore, on Friday, a person should leave work early The custom of the Chazzon Ish was not to travel 7 enough so that he will be able to get home with on Erev Shabbos . plenty of time before Shabbos even if there is traffic along the way. 1 Some say that one who In Eretz Yisroel it is very common for a yid who is traveling to a different city on Erev Shabbos is not frum to drive a cab. One who takes a cab should make sure to reach his destination close to Shabbos should make sure to leave within an hour of Shabbos .2 One who has enough time for the driver to reach his home someone to prepare Shabbos for him can be before Shabbos arrives, since by not doing so 8 lenient with this. 3 There is a discussion in the one is causing him to disgrace the Shabbos . poskim if one can be lenient with this halacha if one brings food with him in the car. 4 Flowers for Shabbos Based on a Medrash in Vayikra 9 it is customary 10 Nonetheless, one should be very careful with to buy flowers in honor of Shabbos . -

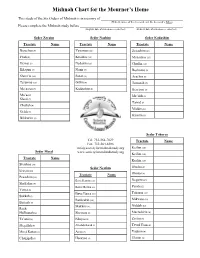

English Mishnah Chart

Mishnah Chart for the Mourner’s Home This study of the Six Orders of Mishnah is in memory of (Hebrew names of the deceased, and the deceased’s father) Please complete the Mishnah study before (English date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) (Hebrew date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) Seder Zeraim Seder Nashim Seder Kodashim Tractate Name Tractate Name Tractate Name Berachos (9) Yevamos (16) Zevachim (14) Peah (8) Kesubos (13) Menachos (13) Demai (7) Nedarim (11) Chullin (12) Kilayim (9) Nazir (9) Bechoros (9) Shevi’is (10) Sotah (9) Arachin (9) Terumos (11) Gittin (9) Temurah (7) Ma’asros (5) Kiddushin (4) Kereisos (6) Ma’aser Me’ilah (6) Sheni (5) Tamid (7) Challah (4) Middos (5) Orlah (3) Kinnim (3) Bikkurim (3) Seder Tohoros Tel: 732-364-7029 Tractate Name Fax: 732-364-8386 [email protected] Keilim (10) Seder Moed www.societyformishnahstudy.org Keilim (10) Tractate Name Keilim (10) Shabbos (24) Seder Nezikin Oholos (9) Eruvin (10) Tractate Name Oholos (9) Pesachim (10) Bava Kamma (10) Negaim (14) Shekalim (8) Bava Metzia (10) Parah (12) Yoma (8) Bava Basra (10) Tohoros (10) Sukkah (5) Sanhedrin (11) Mikvaos (10) Beitzah (5) Makkos (3) Niddah (10) Rosh HaShanah (4) Shevuos (8) Machshirin (6) Ta’anis (4) Eduyos (8) Zavim (5) Megillah (4) Avodah Zarah (5) Tevul Yom (4) Moed Kattan (3) Avos (5) Yadaim (4) Chagigah (3) Horayos (3) Uktzin (3) • Our Sages have said that Asher, son of the Patriarch Jacob sits at the opening to Gehinom (Purgatory), and saves [from entering therein] anyone on whose behalf Mishnah is being studied . -

High Holy Days Q&A Full Sheet.Indd

The High Holy Days Questions and Answers to help you more fully experience and enjoy these Holy Days What do the words Rosh Hashanah mean? Rosh Hashanah is Hebrew for “head of the year” (literally) or “beginning of the year” (figuratively). In the Torah, we read, “In the seventh month, on the first day of the month, there shall be a sacred assembly, a cessation from work, a day of commemoration proclaimed by the sound of the Shofar.” Therefore, we celebrate Rosh Hashanah on the first and second days of Tishrei, the seventh month of the Jewish calendar. Why is the New Year in the Fall? Why do we start the New Year in the seventh month? Our ancestors had several dates in the calendar marking the beginning of important seasons of the year. The first month of the Hebrew calendar was Nisan, in the spring. The fifteenth day of the month of Shevat was considered the New Year of the Trees. But the first of Tishrei was the beginning of the economic year, when the old harvest year ended and the new one began. Around the month of Tishrei, the first rains came in the Land of Israel, and the soil was plowed for the winter grain. Eventually, the first of Tishrei became not only the beginning of the economic year, but the beginning of the spiritual year as well. What are the “Days of Awe?” Rosh Hashanah is the first of the “High Holy Days,” and begins the most spiritually intense part of the Jewish year – the yamin nora’im, the Days of Awe. -

Is Chomesh a Kapara?

בס"ד Volume 13. Issue 28 Is Chomesh a Kapara? Only a Kohen is allowed to eat terumah. If someone else be the recipient, fits with our understanding that payment of does so by mistake, then they need to pay the value of what keren and chomesh is mean of kapara for the past violation. was consumed (keren) and an additional chomesh (6:1). Chomesh literally means a fifth, however it is a fifth of the The Mishnah Rishona however understands that keren alone total value once it is added with the principle amount. In is for kapara and not chomesh. Consequently, while the other words, it is a quarter of the original value. The payment keren must be separated, even if she is allowed to keep it, the is the form of regular tithed produce and it becomes terumah. chomesh does not need to separated or designated. He We also learnt from a number of Mishnayot that there is a suggests that this is implied by the Bartenura who explains difference between the keren and chomesh. For example that in the second case, she can withhold the chomesh. The (6:2), if one ate terumah belonging to a particular Kohen, the Barteunrau however does now write, that the chomesh must keren is paid to that Kohen while the chomesh may be paid be separated and can be kept. to any Kohen. The Mishnah Rishona (3:1) uses this distinction to explain If however one eats terumah deliberately, then he only pays why one who eats safek (doubtful) terumah is exempt from the keren and not the chomesh.