MARKETING MIX and BRANDING: COMPETITIVE HYPERMARKET STRATEGIES Hui-Chu Chen, Transworld Institute of Technology Robert D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hypermarket Format: Any Future Or a Real Need to Be Changed? an Empirical Study of the French, Spanish and Italian Markets

Hypermarket Format: Any Future or a Real Need to Be Changed? An Empirical Study of the French, Spanish and Italian markets. Rozenn PERRIGOT ESC Rennes School of Business CREM UMR CNRS 6211 2, rue Robert d’Arbrissel CS 76522 35065 Rennes Cedex FRANCE [email protected] Gérard CLIQUET Institute of Management of Rennes (IGR-IAE) University of Rennes 1 CREM UMR CNRS 6211 11, rue Jean Macé CS 70803 35708 Rennes Cedex FRANCE [email protected] 5th International Marketing Trends Congress, Venice (ITALY), 20-21 of January 2006 Hypermarket Format: Any Future or a Real Need to Be Changed? An Empirical Study of the French, Spanish and Italian markets. Abstract: The hypermarket appeared first in France at the beginning of the sixties as a synthesis of the main features of modern retailing. But in France, the decline of this retail format seems to have begun and Spain could follow quickly. In the same time, the German hard-discounters continue their invasion. According to the retail life cycle theory, this paper displays curves to demonstrate the evolution of this retail concept in France, Spain and Italy and tries to evoke some managerial and strategic issues. The retail wheel seems to go on turning! Keywords: France, hypermarket, Italy, retail life cycle, Spain, wheel of retailing. 1. Introduction The history of modern retailing began more than 150 years ago. The first retailing formats began to outcompete the traditional small and independent shops. For instance, many department stores followed several decades later by variety stores appeared in Europe (France, UK, Germany and Italy) but also in the United States and Japan. -

Serving Customers in Diverse Ways Products Ecommerce

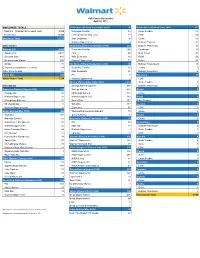

eCommerce Products Truffles Donckels brand from Belgium is available One of the reasons behind Walmart Brazil’s in both Sam’s Club and Walmart. Additionally, success is their ability to leverage scale and Walmart Brazil imports Hunts Tomato Sauce, expertise to be one of the top leaders among online Cheesecake Factory and Samuel Adams beer to retailers in market share and provide low, Sam’s Club stores. competitive prices. In addition, walmart.com.br is able to present a huge variety and assortment of Borges Olive Oil and McCain French Fries are part general merchandise, usually larger than brick and of the portfolio for Walmart Brazil. As of 2015, the Serving Customers mortar operations. Brazilian consumer can buy children’s clothing Child of Mine, developed by Carter’s in the United In Diverse Ways States, exclusively at Walmart. History “Orbit” chewing gum, Starburst and “5” gum, from Walmart Brazil began its Wrigley (Mars, Incorporated), was available to operations in 1995, with its Economic Impact Brazil in 2014, exclusively at Walmart stores in all headquarters located in Barueri, regions. São Paulo. Walmart Brazil Over the past 12 years, Walmart Brazil’s Producer’s operates across 18 states and the Club has grown to 9,221 households in 18 Brazilian Schwinn, a traditional bike brand in USA, now offers Federal District, serving 1 million states and the Federal District. It offers these Mountain, Dakota, Colorado and Eagle bike models customers each day with suppliers access to Walmart Brazil stores to sell in Brazil through Walmart hypermarket formats. hypermarkets, supermarkets, cash their products. -

RSCI Pioneered the Hypermarket Concept in the Philippines Through Shopwise

Rustan Supercenters, Inc. (RSCI), a member of the Rustan Group of Companies, was founded in 1998 at the height of the Asian Economic Crisis. It was the first Rustan Company to take in outside investors. It was also the Rustan Group’s first major foray into the discount retailing segment through an adapted European style hypermarket. RSCI pioneered the hypermarket concept in the Philippines through Shopwise. Armed with the vision of providing Quality for All, the Company sought to make the renowned Rustan’s quality accessible to all, especially the middle and working class. Its mission is to create a chain of supercenters or hypermarkets which is the needs of the Filipino family. Rustan’s decision to diversify into hypermarkets was borne out of manifest opportunities brought about by fundamental changes that are taking place in the Philippine market: a burgeoning middle class; increasing value consciousness across various income levels; and new geographical market opportunities that are best served through discount retailing operations. RSCI developed and opened the first hypermarket in the country in November 29, 1998 in Alabang. From 40 employees, it now employs more than 6,000 employees The Company has attained much success since its inception. From 40 employees, it now employs more than 6,000 employees. From sales of zero, the Company registered sales of over P17B in fiscal year 2012-2013. From one hypermarket in Filinvest Alabang, it has now grown to 46 stores covering multiple retail formats, namely, hypermarkets, upscale supermarkets, and neighborhood grocery stores. November 2006 marked yet another milestone for RSCI when it has acquired the 21 Rustan’s stores and food services operations under an Asset Lease Agreement. -

2019 Philippines Food Retail Sectoral Report

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 7/8/2019 GAIN Report Number: 1913 Philippines Retail Foods 2019 Food Retail Sectoral Report Approved By: Ryan Bedford Prepared By: Joycelyn Claridades Rubio Report Highlights: The Philippine food retail sector continues to grow, providing opportunities for increased exports of U.S. high-value food and beverages. The food retail industry sold a record $47.4 billion in 2018, and Post forecasts sales in 2019 at nearly $50 billion. Driven by rising incomes, a growing population, and a strong preference for American brands, the Philippines imported $1.09 billion of U.S. consumer-oriented products in 2018. Post expects U.S. exports in this sector to grow further in 2019, reaching an all-time high of $1.2 billion. Market Fact Sheet: Philippines With a population of 105.9 million and decreasing farmlands, the Philippines is dependent on food imports. In 2018, Philippine imports of high-value food products from the United States reached $1.09 billion, making the United States the largest supplier for high-value, consumer-oriented food and beverage products. Post expects this to continue in 2019, with exports forecast to grow 10 percent to $1.2 billion. The Philippines continues to be one of the fastest-growing economies in Asia. With a growing middle class and a large, young population, the Philippine economy is rooted in strong consumer demand, boosted by rising incomes and overseas remittances. Per capita gross income and consumer expenditures saw strong gains from 2012 to 2018. -

1 Acapulco: Big Box Nirvana

ACAPULCO: BIG BOX NIRVANA - HYPERMARKET HEAVEN FAST FACTS Similar To Urbanized Area* Population 700,000 Brasilia, Hamilton, Malaga Urbanized Land Area: Square Miles 45 Rosario, Kelowna, Geneva Urbanized Land Area: Square Kilometers 116 Population per Square Mile 15,600 Manaus, London, Jakarta Population per Square Kilometer 6,000 *Continuously built up area 21 August 2004 Acapulco is what you would expect for a resort. It is Mexico’s original and premier seaside Pacific coast tourist destination. Acapulco is located a little more than 200 miles south of the Zona Rosa in Mexico City. Convenient access is provided via the west and south side Periferico (parts of which are under construction for double decking) and the toll D-95, which exits Periferico at Tlalpan. It is an expensive ride, with gross tolls over $40. Petrol, however, is not nearly so onerously taxed as in Europe, so that prices are near American levels --- still among the most heavily taxed products in either of the United States (of Mexico or America, the official name of Mexico is Estados Unidos de Mexicanos). The trip is picturesque, with a number of mountain passes. The speed limit is 110 kilometers per hour, but it is clear that respect for the limit is more on a par with Italy or Spain rather than America. The entire route can easily be driven in a bit over three hours, assuming good traffic conditions in Mexico City, a Acapulco Urbanized Area perhaps optimistic assumption. MICROSOFT “STREETS & TRIPS” MAP Acapulco is the largest city in the state of Guerrero, though the capital is Chilpancingo de los Bravos, through which the toll route is interrupted 60 miles north of Acapulco. -

Hypermarket Lessons for New Zealand a Report to the Commerce Commission of New Zealand

Hypermarket lessons for New Zealand A report to the Commerce Commission of New Zealand September 2007 Coriolis Research Ltd. is a strategic market research firm founded in 1997 and based in Auckland, New Zealand. Coriolis primarily works with clients in the food and fast moving consumer goods supply chain, from primary producers to retailers. In addition to working with clients, Coriolis regularly produces reports on current industry topics. The coriolis force, named for French physicist Gaspard Coriolis (1792-1843), may be seen on a large scale in the movement of winds and ocean currents on the rotating earth. It dominates weather patterns, producing the counterclockwise flow observed around low-pressure zones in the Northern Hemisphere and the clockwise flow around such zones in the Southern Hemisphere. It is the result of a centripetal force on a mass moving with a velocity radially outward in a rotating plane. In market research it means understanding the big picture before you get into the details. PO BOX 10 202, Mt. Eden, Auckland 1030, New Zealand Tel: +64 9 623 1848; Fax: +64 9 353 1515; email: [email protected] www.coriolisresearch.com PROJECT BACKGROUND This project has the following background − In June of 2006, Coriolis research published a company newsletter (Chart Watch Q2 2006): − see http://www.coriolisresearch.com/newsletter/coriolis_chartwatch_2006Q2.html − This discussed the planned opening of the first The Warehouse Extra hypermarket in New Zealand; a follow up Part 2 was published following the opening of the store. This newsletter was targeted at our client base (FMCG manufacturers and retailers in New Zealand). -

Hyper Market Industry in Dubai – an Evaluation Using Ahp Technique

50____________________________________________________________ iJAMT HYPER MARKET INDUSTRY IN DUBAI – AN EVALUATION USING AHP TECHNIQUE M. Hemalatha, National Institute of Technology, Trichy V. J. Sivakumar, National Institute of Technology, Trichy Abstract Among all retail formats hypermarket is growing very fast in UAE that is at the rate of 150 percent. The major players in this sector are Carrefour, Spinney’s, United, Choithram and Lulu. The focus of the problem is selecting a best hypermarket among the existing operators of Dubai and for which we used seven major criteria for evaluating the hypermarkets such as product availability and variety, market coverage, channel density, customer density, nationality served, facilities and services and customer spending pattern. We used Analytic hierarchy process (AHP), developed by Thomas saaty (1980) to provide a simple but theoretically sound multiple criteria methodology for evaluating the alternatives. Keywords Hyper Market, Analytic hierarchy process, Multiple Criteria Introduction about UAE Hyper Market Industry The retail sector in the United Arab Emirates (U.A.E.) continues to grow and develop a process that began in earnest nearly 10 years ago. Annually, many new state of the art stores are added to the country’s retail map, creating continuous competition among the major retailers. The new stores match Western retail establishments in size and variety. The estimated annual value of the U.A.E. retail market is $2.5 billion. The estimated average annual growth in retail sales is 5-10 percent. First year retail establishments report higher growth rates than those claimed by established firms. Foods sold in retail outlets consist 75-80 percent of imported consumer-ready products, and 20-25 percent of locally processed foods. -

WMT Detailed Unit Count FY2018

Unit Counts by Country April 30, 2017 WORLDWIDE TOTALS El Salvador (Entered September 2005) 90 South Africa (Entered June 2011) 377 Total U.S. (Walmart US & Sam's Club) 5,354 Despensa Familiar 60 Game Foodco 70 International 6,369 La Despensa de Don Juan 17 CBW 48 Worldwide Total 11,723 Maxi Despensa 9 Game 50 Walmart Supercenter 4 Builders Express 43 United States Guatemala (Entered September 2005) 221 Builders Warehouse 33 Walmart U.S. 4,692 Despensa Familiar 154 Cambridge 38 Supercenter 3,534 Paiz 25 Dion Wired 24 Discount Store 412 Maxi Despensa 32 Rhino 20 Neighborhood Market 698 Walmart Supercenter 10 Makro 20 Amigo 18 Honduras (Entered September 2005) 98 Builders Trade Depot 15 E-Commerce Acquisition / C-stores 14 Despensa Familiar 65 Jumbo 7 Other Store formats 16 Maxi Despensa 22 Builders Superstore 9 Sam's Club 662 Paiz 8 Botswana 11 United States Total 5,354 Walmart Supercenter 3 CBW 7 Mexico (Entered November 1991) 2,412 Game Foodco 2 International Bodega Aurrera Express 940 Builders Warehouse 2 Argentina (Entered August 1995) 108 Bodega Aurrera 490 Ghana 1 Changomas 52 Mi Bodega Aurrera 331 Game 1 Walmart Supercenter 32 Walmart Supercenter 263 Kenya 1 Changomas Express 10 Sam's Club 161 Game Foodco 1 Mi Changomas 8 Suburbia 117 Lesotho 3 Walmart Supermercado 6 Superama 95 CBW 2 Brazil (Entered May 1995) 498 Medimart Farmacia de Walmart 10 Game 1 Todo Dia 150 Zona Suburbia 5 Malawi 2 Nacional (Sonae) 55 Nicaragua (Entered September 2005) 93 Game 2 Supermarket (Bompreco) 59 Pali 66 Mozambique 5 Walmart Supercenter 55 Maxi Pali -

Introducing Target Into Singapore 1

Running head: INTRODUCING TARGET INTO SINGAPORE 1 Introducing Target into Singapore Yealim Ko A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Fall 2013 INTRODUCING TARGET INTO SINGAPORE 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Kendrick W. Brunson, D.B.A. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Nancy J. Kippenhan, M.B.A. Committee Member ______________________________ JJ Cole, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date INTRODUCING TARGET INTO SINGAPORE 3 Abstract The global business trends point to international expansions with corporations increasingly turning to emerging markets for new opportunities to grow and create new sources of revenues. While the BRIC countries including Brazil, Russia, India, and China remain at the center of attention from global industries, the surrounding countries in Asia including Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, and Singapore emerge as potential markets because although smaller in size, the surrounding countries with fast growing economy and consumer demand for foreign goods suggest large profit potentials. Considering the increasing trend of going abroad in the retail industry (S&P, 2013), the paper is an analysis of the potential of Singapore as a desirable market for U.S. retail industry by conducting a feasibility analysis of implementing the Target store brand into Singapore. The analysis includes cultural analysis, economic analysis, and market audit as well as competitive market analysis which will, in turn, provide deeper understanding of the existing markets in Singapore; therefore, provided basis for potential market expansion of other domestic business into Singapore. -

Structural Changes in Food Retailing: Six Country Case Studies

FSRG Publication Structural Changes in Food Retailing: Six Country Case Studies edited by Kyle W. Stiegert and Dong Hwan Kim FSRG Publication, November 2009 FSRG Publication Structural Changes in Food Retailing: Six Country Case Studies edited by Kyle W. Stiegert Dong Hwan Kim November 2009 Kyle Stiegert [email protected] The authors thank Kate Hook for her editorial assistance. Any mistakes are those of the authors. Comments are encouraged. Food System Research Group Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics University of Wisconsin-Madison http://www.aae.wisc.edu/fsrg/ All views, interpretations, recommendations, and conclusions expressed in this document are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the supporting or cooperating organizations. Copyright © by the authors. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for noncommercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. ii Chapter 7: Food Retailing in the United States: History, Trends, Perspectives Kyle W. Stiegert and Vardges Hovhannisyan 1. INTRODUCTION: FOOD RETAILING: 1850-1990 Before the introduction of supermarkets, fast food outlets, supercenters, and hypermarts, various other food retailing formats operated successfully in the US. During the latter half of the 19th century, the chain store began its rise to dominance as grocery retailing format. The chain grocery store began in 1859 when George Huntington Hartford and George Gilman founded The Great American Tea Company, which later came to be named The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company (Adelman, 1959). The typical chain store was 45 to 55 square meters, containing a relatively limited assortment of goods. -

Retail Scene Report

GFSI CONFERENCE 2020 – DISCOVERY TOURS 25th February | Seattle, USA Retail Scene Report Seattle, Washington State & America’s Pacific Northwest 19 The Consumer Goods Forum GFSI CONFERENCE 2020 – DISCOVERY TOURS 25th February | Seattle, USA Retail Scene Report Seattle, Washington State & America’s Pacific Northwest FEBRUARY 2020 Kantar Consulting for The Consumer Goods Forum’s GFSI Conference 2020 20 The Consumer Goods Forum GFSI CONFERENCE 2020 – DISCOVERY TOURS 25th February | Seattle, USA Contents Seattle, Washington State & America’s Pacific Northwest .............. 22 Food Retail in the Pacific Northwest ........................................................ 24 Supercenters & Warehouse Clubs ........................................................ 27 Supermarkets & Convenience Stores .................................................. 29 Full-Service Supermarkets .................................................................. 29 Value/Private-Label Supermarkets ................................................ 32 Convenience Stores ................................................................................ 34 Food Safety in America & Washington State ......................................... 35 The US Federal Government & Agencies ........................................... 35 Washington State Food Safety ................................................................ 36 City, Town, & Local Food Safety ............................................................ 37 Conclusions ........................................................................................................ -

Case Study Carrefour Hypermarket

Case study Carrefour Hypermarket Location Santiago de Compostela, Spain Philips Lighting Philips LED Lighting solutions, Dynalite Control System Background The challenge The Carrefour Company was founded in 1959 and opened its first Wherever it has a presence, Carrefour is actively committed to supermarket the following year. Since these humble beginnings, promoting neighborhood economic development and supporting the company has continued to grow and today the Carrefour nearby suppliers. To this end, 90 to 95 per cent of the products on its Group is the largest retailer in Europe and the second largest shelves are sourced locally. Moreover, mindful of the social, economic in the world. Operating four distinct grocery store formats – and environmental impact of its activities, the Carrefour Group has hypermarkets, supermarkets, cash-and-carry and convenience placed sustainable development at the heart of its business strategy, stores – the Carrefour group currently has over 9,500 stores with this approach focused on two key areas: to integrate sustainable across 32 countries, through a combination of company-operated development into the management of its business; and to increase and franchise outlets. client awareness of sustainable development. When the Carrefour Group decided to build a new hypermarket at the Las Cancelas shopping center on the Avenida do Camiño Francés, in Santiago de Compostela in north-western Spain, the company wanted to incorporate an energy-efficient lighting solution to complement its corporate sustainability goals. It was important It was important for Carrefour to match lighting levels and effects with group lighting standards for its hypermarkets. The solution also needed to achieve significant energy savings – compared with its for Carrefour standard lighting solutions – and reduce ongoing maintenance costs as much as possible.