IDP 2011 Eng Cover Master

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation Forest Department

Leaflet No. 24 The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation Forest Department Assessing different livelihood of the local people and causes of forest degradation and deforestation in the Kayah State Dr. Chaw Chaw Sein, Staff Officer Dr. Thaung Naing Oo, Director Kyi Phyu Aung, Range Officer Forest Research Institute December, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS i Abstract ii 1 Introduction 1 2 Objectives 2 3 Literature Review 2 3.1 What do we mean by sustainable livelihoods? 2 3.2 Why are sustainable livelihoods important for conservation? 3 3.3 How do we identify locally appropriate livelihoods strategies? 3 4 Material and Method 5 4.1 Study Area 5 4.2 Data collection and analysis 6 5 Results and Discussion 6 5.1 Livelihood surveys in the Kayah Region 6 5.2 Causes of forest degradation and deforestation in the study area 12 6 Conclusions and Recommendation 15 7 Acknowledgements 17 8 References 18 ၊ ၊ ၊ ၊ ၁.၄% Assessing different livelihood of the local people and causes of forest degradation and deforestation in the Kayah State Dr. Chaw ChawSein, Staff Officer Dr. Thaung Naing Oo, Director Thein Saung, Staff Officer Kyi Phyu Aung , Range Officer Abstract About annual rate of 1.4% of the forest degradation and deforestation was occurred in Myanmar. There are many causes of deforestation and forest degradation. Especially in the hilly region like Kayah state, the main causes of forest degradation and deforestation are due to shifting cultivation. The present study reports different livelihood activities to settle their daily needs in the Kayah areas and the causes of forest degradation and deforestation. -

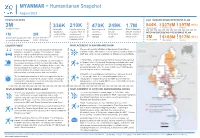

Myanmar – Humanitarian Snapshot (August 2021)

MYANMAR – Humanitarian Snapshot August 2021 PEOPLE IN NEED 2021 HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE PLAN 3M 336K 210K 470K 249K 1.7M 944K $276M $97M (35%) People targeted Requirements Received People in need Internally People internally Non-displaced Returnees and Other vulnerable displaced displaced due to stateless locally people, mostly in INTERIM EMERGENCY RESPONSE PLAN 1M 2M people at the clashes and persons in integrated urban and peri- start of 2021 Rakhine people urban areas people previously identified people identified insecurity since 2M $109M $17M (15%) February 2021 in conflict-affected areas since 1 February People targeted Requirements Received COUNTRYWIDE DISPLACEMENT IN KACHIN AND SHAN A total of 3 million people are targeted for humanitarian The overall security situation in Kachin and Shan states assistance across the country. This includes 1 million remains volatile, with various level of clashes reported between people in need in conflict-affected areas previously MAF and ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) or among EAOs. identified and a further 2 million people since 1 February. Monsoon flash floods affected around 125,000 people in In Shan State, small-scale population movement was reported the regions and states of Kachin, Kayin, Mandalay, Mon, in Hsipaw, Muse, Kyethi and Mongkaing townships since mid- Rakhine, eastern Shan and Tanintharyi between late July July. In total, 24,950 people have been internally displaced and mid-August, according to local actors. Immediate across Shan State since the start of 2021; over 5,000 people needs of families affected or evacuated have been remain displaced in five townships. addressed by local aid workers and communities. In Kachin, no new displacement has been reported. -

Shan State - Myanmar

Myanmar Information Management Unit SHAN STATE - MYANMAR Mohnyin 96°40'E Sinbo 97°30'E 98°20'E 99°10'E 100°0'E 100°50'E 24°45'N 24°45'N Bhutan Dawthponeyan India China Bangladesh Myo Hla Banmauk KACHIN Vietnam Bamaw Laos Airport Bhamo Momauk Indaw Shwegu Lwegel Katha Mansi Thailand Maw Monekoe Hteik Pang Hseng (Kyu Koke) Konkyan Cambodia 24°0'N Muse 24°0'N Muse Manhlyoe (Manhero) Konkyan Namhkan Tigyaing Namhkan Kutkai Laukkaing Laukkaing Mabein Tarmoenye Takaung Kutkai Chinshwehaw CHINA Mabein Kunlong Namtit Hopang Manton Kunlong Hseni Manton Hseni Hopang Pan Lon 23°15'N 23°15'N Mongmit Namtu Lashio Namtu Mongmit Pangwaun Namhsan Lashio Airport Namhsan Mongmao Mongmao Lashio Thabeikkyin Mogoke Pangwaun Monglon Mongngawt Tangyan Man Kan Kyaukme Namphan Hsipaw Singu Kyaukme Narphan Mongyai Tangyan 22°30'N 22°30'N Mongyai Pangsang Wetlet Nawnghkio Wein Nawnghkio Madaya Hsipaw Pangsang Mongpauk Mandalay CityPyinoolwin Matman Mandalay Anisakan Mongyang Chanmyathazi Ai Airport Kyethi Monghsu Sagaing Kyethi Matman Mongyang Myitnge Tada-U SHAN Monghsu Mongkhet 21°45'N MANDALAY Mongkaing Mongsan 21°45'N Sintgaing Mongkhet Mongla (Hmonesan) Mandalay Mongnawng Intaw international A Kyaukse Mongkaung Mongla Lawksawk Myittha Mongyawng Mongping Tontar Mongyu Kar Li Kunhing Kengtung Laihka Ywangan Lawksawk Kentung Laihka Kunhing Airport Mongyawng Ywangan Mongping Wundwin Kho Lam Pindaya Hopong Pinlon 21°0'N Pindaya 21°0'N Loilen Monghpyak Loilen Nansang Meiktila Taunggyi Monghpyak Thazi Kenglat Nansang Nansang Airport Heho Taunggyi Airport Ayetharyar -

Financial Inclusion

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 I LIFT Annual Report 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 II III LIFT Annual Report 2020 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADB Asian Development Bank LBVD Livestock Breeding and Veterinary ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Department CBO Community-based Organisation We thank the governments of Australia, Canada, the European Union, LEARN Leveraging Essential Nutrition Ireland, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and CSO Civil Society Organisation Actions To Reduce Malnutrition project the United States of America for their kind contributions to improving the livelihoods and food security of rural poor people in Myanmar. Their DAR Department of Agricultural MAM Moderate acute malnutrition support to the Livelihoods and Food Security Fund (LIFT) is gratefully Research acknowledged. M&E Monitoring and evaluation DC Donor Consortium MADB Myanmar Agriculture Department of Agriculture Development Bank DISCLAIMER DoA DoF Department of Fisheries MEAL Monitoring, evaluation, This document is based on information from projects funded by LIFT in accountability and learning 2020 and supported with financial assistance from Australia, Canada, the DRD Department for Rural European Union, Ireland, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, the United Development MoALI Ministry of Agriculture, Kingdom, and the United States of America. The views expressed herein Livestock and Irrigation should not be taken to reflect the official opinion of the LIFT donors. DSW Department of Social Welfare MoE Ministry of Education Exchange rate: This report converts MMK into -

Power Network Development Project – PPTA Consultant

Power Network Development Project (RRP MYA 50020) Environmental Impact Assessment March 2018 MYA: Power Network Development Project— Transmission Component Prepared by AF-Consult Switzerland Ltd. for the Department of Power Transmission and System Control and the Asian Development Bank. This environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Client Asian Development Bank Project TA 9179-MYA: Power Network Development Project – PPTA Consultant Document Type Transmission Lines EIA Project number 4272 January 2018 www.afconsult.com/switzerland Client Consultant Asian Development Bank AF-Consult Switzerland Ltd 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550, Metro Täfernstrasse 26 Manila, Philippines 5405 Baden/Dättwil Document Information Project TA 9179-MYA: Power Network Development Project – PPTA Consultant Proposal Transmission Lines EIA Proposal number 4272 Department Transmission & Distribution Person responsible Jürgen Brommundt Telephone +41 (0) 56 483 15 35 Fax +41 (0)56 483 17 99 email [email protected] Reference BRJ C:\Users\Armando\JOBS- Document path INTERNATIONAL\AFConsult\Myanmar\ESIA\UpdatedESIA\FinalEIA\20180101- Transmission-EIA-v13.docx NOTE(s): In this report, "$" refers to US dollars unless otherwise stated. This environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. -

Myanmar: the Key Link Between

ADBI Working Paper Series Myanmar: The Key Link between South Asia and Southeast Asia Hector Florento and Maria Isabela Corpuz No. 506 December 2014 Asian Development Bank Institute Hector Florento and Maria Isabela Corpuz are consultants at the Office of Regional Economic Integration, Asian Development Bank. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. Working papers are subject to formal revision and correction before they are finalized and considered published. In this paper, “$” refers to US dollars. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. ADBI encourages readers to post their comments on the main page for each working paper (given in the citation below). Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Florento, H., and M. I. Corpuz. 2014. Myanmar: The Key Link between South Asia and Southeast Asia. ADBI Working Paper 506. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available: http://www.adbi.org/working- paper/2014/12/12/6517.myanmar.key.link.south.southeast.asia/ Please contact the authors for information about this paper. -

Ethnic Armed Actors and Justice Provision in Myanmar

Ethnic Armed Actors and Justice Provision in Myanmar Brian McCartan and Kim Jolliffe October 2016 Preface As a result of decades of ongoing civil war, large areas of Myanmar remain outside government rule, or are subject to mixed control and governance by the government and an array of ethnic armed actors (EAAs). These included ethnic armed organizations, with ceasefires or in conflict with the state, as well as state-backed ethnic paramilitary organizations, such as the Border Guard Forces and People’s Militia Forces. Despite this complexity, order has been created in these areas, in large part through customary justice mechanisms at the community level, and as a result of justice systems administered by EAAs. Though the rule of law and the workings of Myanmar’s justice system are receiving increasing attention, the role and structure of EAA justice systems and village justice remain little known and therefore, poorly understood. As such, The Asia Foundation is pleased to present this research on justice provision and ethnic armed actors in Myanmar, as part of the Foundation’s Social Services in Contested Areas in Myanmar series. The study details how the village, and village-based mechanisms, are the foundation of stability and order for civilians in most of these areas. These systems have then been built through EAA justice systems, which maintain a hierarchy of courts above the village level. Understanding the continuity and stability of these village systems, and the heterogeneity of the EAA justice systems which work alongside them, is essential for understanding civilians’ experiences of justice and security across Myanmar, as well as the opportunities for positive change that exist in Myanmar’s ongoing peace process and governance reforms. -

English 2014

The Border Consortium November 2014 PROTECTION AND SECURITY CONCERNS IN SOUTH EAST BURMA / MYANMAR With Field Assessments by: Committee for Internally Displaced Karen People (CIDKP) Human Rights Foundation of Monland (HURFOM) Karen Environment and Social Action Network (KESAN) Karen Human Rights Group (KHRG) Karen Offi ce of Relief and Development (KORD) Karen Women Organisation (KWO) Karenni Evergreen (KEG) Karenni Social Welfare and Development Centre (KSWDC) Karenni National Women’s Organization (KNWO) Mon Relief and Development Committee (MRDC) Shan State Development Foundation (SSDF) The Border Consortium (TBC) 12/5 Convent Road, Bangrak, Suite 307, 99-B Myay Nu Street, Sanchaung, Bangkok, Thailand. Yangon, Myanmar. E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.theborderconsortium.org Front cover photos: Farmers charged with tresspassing on their own lands at court, Hpruso, September 2014, KSWDC Training to survey customary lands, Dawei, July 2013, KESAN Tatmadaw soldier and bulldozer for road construction, Dawei, October 2013, CIDKP Printed by Wanida Press CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 3 1.1 Context .................................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Methodology ........................................................................................................................ -

Chapter 6 South-East Asia

Chapter 6 South-East Asia South-East Asia is the least compact among the extremity of North-East Asia. The contiguous ar- regions of the Asian continent. Out of its total eas constituting the continental interior include land surface, estimated at four million sq.km., the the highlands of Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and mainland mass has a share of only 40 per cent. northern Vietnam. The relief pattern is that of a The rest is accounted for by several thousand is- longitudinal ridge and furrow in Myanmar and lands of the Indonesian and Philippine archipela- an undulating plateau eastwards. These are re- goes. Thus, it is composed basically of insular lated to their structural difference: the former and continental components. Nevertheless the being a zone of tertiary folds and the latter of orographic features on both these landforms are block-faulted massifs of greater antiquity. interrelated. This is due to the focal location of the region where the two great axes, one of lati- The basin of the Irrawady (Elephant River), tudinal Cretaceo-Tertiary folding and the other forming the heartland of Myanmar, is ringed by of the longitudinal circum-Pacific series, converge. mountains on three sides. The western rampart, This interface has given a distinctive alignment linking Patkai, Chin, and Arakan, has been dealt to the major relief of the region as a whole. In with in the South Asian context. The northern brief, the basic geological structures that deter- ramparts, Kumon, Kachin, and Namkiu of the mine the trend of the mountains are (a) north- Tertiary fold, all trend north-south parallel to the south and north-east in the mainland interior, (b) Hengduan Range and are the highest in South- east-west along the Indonesian islands, and (c) East Asia; and this includes Hkakabo Raz north-south across the Philippines. -

PA) PROFILES LENYA LANDSCAPE (“R2R Lenya”, Aka Lenya Proposed Protected Area, Which Is Currently Lenya Reserved Forest

ANNEX 11: Lenya Profile LANDSCAPE / SEASCAPE AND PROTECTED AREA (PA) PROFILES LENYA LANDSCAPE (“R2R Lenya”, aka Lenya Proposed Protected Area, which is currently Lenya Reserved Forest) Legend for this map of Lenya Landscape is provided at the end of this annex. I. Baseline landscape context 1. 1 Defining the landscape: Lenya Landscape occupies the upper Lenya River Basin in Kawthaung District, and comprises the Lenya Proposed National Park (LPNP), which was announced in 2002 for the protection of Gurney’s pitta and other globally and nationally important species, all of which still remain (see below). The LPNP borders align with those of the Lenya Reserve Forest (RF) under which the land is currently classified, however its status as an RF has to date not afforded it the protection from encroachment and other destructive activities to protect the HCVs it includes. The Lenya Proposed National Park encompasses an area of 183,279ha directly south of the Myeik-Kawthaung district border, with the Lenya Proposed National Park Extension boundary to the north, the Parchan Reserve Forest to the south and the Thai border to the east. The site is located approximately 260km south of the regional capital of Dawei and between 20-30km east of the nearest administrative town of Bokpyin. Communities are known to reside within the LPNP area as well as on its immediate boundaries across the LPNP. Some small settled areas can be found in the far south-east, along the Thai border, where heavy encroachment by smallholder agriculture can also be found and where returning Myanmar migrants to Thailand may soon settle; Karen villages which have resettled (following the signing of a peace treaty between the Karen National Union (KNU) and the Myanmar government) on land along the Lenya River extending into the west of LPNP; and in the far north where a significant number of hamlets (in addition to the Yadanapon village) have developed in recent years along the the Yadanapon road from Lenya village to Thailand. -

Karen Community Consultation Report

Karen Community Consultation report 28th March 2009 Granville Town Hall Acknowledgements The Karen community consultation report was first compiled in June 2009 by the working group comprising of, Rhianon Partridge, Wah Wah Naw, Daniel Zu, Lina Ishu and Gary Cachia, with additional input provided by Jasmina Bajraktarevic Hayward This report and consultation was made possible by the relationships developed between STARTTS and the Karen community in Sydney and in particular with the Australian Karen Organisation. Special thanks to all people who participated in the consultation A copyright for this report belongs to STARTTS. Parts of the report may be reused for educational and non profit purposes without permission of STARTTS provided the report is adequately sourced. The report may be distributed electronically without permission. For further information or permissions please contact STARTTS on 02 97941900 STARTTS Karen Community Consultation Report Page 2 of 48 Contents Karen Information ........................................................................................................ 4 • Some of the history .............................................................................................. 4 • Persecution Past and Present ................................................................................ 7 • Demographics .................................................................................................... 13 • Karen Cultural information ............................................................................... -

Kayah State Myanmar South East Operation - UNHCR Hpa-An 31 March 2016

Return Assessments - Kayah State Myanmar South East Operation - UNHCR Hpa-An 31 March 2016 Background information Since June 2013, UNHCR has been piloting a system to assess spontaneous returns in the Southeast of Myanmar, a process that may start in the absence of an organized Voluntary Repatriation operation. Total Assessments 128 A verified return village, therefore, is a village where UNHCR field staff have confirmed there are refugees and/or IDPs who have returned since January 2012 with the intention of remaining Verified Return Villages permanently. During the assessments, communities are also asked whether their village is a refugee 44 village of origin, by definition a village that is home to people residing in a refugee camp in Thailand. A village where UNHCR completes an assessment can be both a verified return village and a refugee Refugee Villages of Origin 94 village of origin, as the two are not mutually exclusive. Using a “do no harm” approach based around community level discussion, the return assessment collect information about the patterns and needs of returnees in the Southeast. The project does not, however, attempt to represent the total number of returnees in a state, or the region as a whole. The returnee monitoring project has been underway in Kayah State, Mon State and Tanintharyi Region since June 2013, and expanded to Kayin State in December 2013. Verified Return Villages by Township ^^ ± Demoso 8 26 ^^^ ^^^^^ Hpasawng 11 ^ ^_^ ^ 5 ^ Loikaw 6 29 ^ ^_ Shadaw 19 ^ ^_ ^ 14 Shan (South) ^ ^_ ^ Bawlakhe 5 ^_Loikaw 2 ^ ^ ^_ Hpruso 7 29 ^_ ^_ ^_^_^_ Shadaw Mese 9 ^ ^_^_ ^ 2 ^^ ^_ ^_Demoso^^ ^_ Assessments Verified Return Villages ^^^ ^_^_ ^ ^ ^_ ^ ^_ ^^_^ ^^^ ^_ No.