3Sigma Function During Mitosis in Caenorhabditis Elegans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Stratify Clinical Response to csDMARD-Therapy and Predict Radiographic Progression Frances Humby1,* Myles Lewis1,* Nandhini Ramamoorthi2, Jason Hackney3, Michael Barnes1, Michele Bombardieri1, Francesca Setiadi2, Stephen Kelly1, Fabiola Bene1, Maria di Cicco1, Sudeh Riahi1, Vidalba Rocher-Ros1, Nora Ng1, Ilias Lazorou1, Rebecca E. Hands1, Desiree van der Heijde4, Robert Landewé5, Annette van der Helm-van Mil4, Alberto Cauli6, Iain B. McInnes7, Christopher D. Buckley8, Ernest Choy9, Peter Taylor10, Michael J. Townsend2 & Costantino Pitzalis1 1Centre for Experimental Medicine and Rheumatology, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, Charterhouse Square, London EC1M 6BQ, UK. Departments of 2Biomarker Discovery OMNI, 3Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, Genentech Research and Early Development, South San Francisco, California 94080 USA 4Department of Rheumatology, Leiden University Medical Center, The Netherlands 5Department of Clinical Immunology & Rheumatology, Amsterdam Rheumatology & Immunology Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 6Rheumatology Unit, Department of Medical Sciences, Policlinico of the University of Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy 7Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8TA, UK 8Rheumatology Research Group, Institute of Inflammation and Ageing (IIA), University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2WB, UK 9Institute of -

TITLE PAGE Oxidative Stress and Response to Thymidylate Synthase

Downloaded from molpharm.aspetjournals.org at ASPET Journals on October 2, 2021 -Targeted -Targeted 1 , University of of , University SC K.W.B., South Columbia, (U.O., Carolina, This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. -

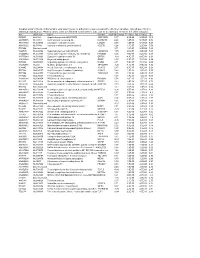

Supplementary File 2A Revised

Supplementary file 2A. Differentially expressed genes in aldosteronomas compared to all other samples, ranked according to statistical significance. Missing values were not allowed in aldosteronomas, but to a maximum of five in the other samples. Acc UGCluster Name Symbol log Fold Change P - Value Adj. P-Value B R99527 Hs.8162 Hypothetical protein MGC39372 MGC39372 2,17 6,3E-09 5,1E-05 10,2 AA398335 Hs.10414 Kelch domain containing 8A KLHDC8A 2,26 1,2E-08 5,1E-05 9,56 AA441933 Hs.519075 Leiomodin 1 (smooth muscle) LMOD1 2,33 1,3E-08 5,1E-05 9,54 AA630120 Hs.78781 Vascular endothelial growth factor B VEGFB 1,24 1,1E-07 2,9E-04 7,59 R07846 Data not found 3,71 1,2E-07 2,9E-04 7,49 W92795 Hs.434386 Hypothetical protein LOC201229 LOC201229 1,55 2,0E-07 4,0E-04 7,03 AA454564 Hs.323396 Family with sequence similarity 54, member B FAM54B 1,25 3,0E-07 5,2E-04 6,65 AA775249 Hs.513633 G protein-coupled receptor 56 GPR56 -1,63 4,3E-07 6,4E-04 6,33 AA012822 Hs.713814 Oxysterol bining protein OSBP 1,35 5,3E-07 7,1E-04 6,14 R45592 Hs.655271 Regulating synaptic membrane exocytosis 2 RIMS2 2,51 5,9E-07 7,1E-04 6,04 AA282936 Hs.240 M-phase phosphoprotein 1 MPHOSPH -1,40 8,1E-07 8,9E-04 5,74 N34945 Hs.234898 Acetyl-Coenzyme A carboxylase beta ACACB 0,87 9,7E-07 9,8E-04 5,58 R07322 Hs.464137 Acyl-Coenzyme A oxidase 1, palmitoyl ACOX1 0,82 1,3E-06 1,2E-03 5,35 R77144 Hs.488835 Transmembrane protein 120A TMEM120A 1,55 1,7E-06 1,4E-03 5,07 H68542 Hs.420009 Transcribed locus 1,07 1,7E-06 1,4E-03 5,06 AA410184 Hs.696454 PBX/knotted 1 homeobox 2 PKNOX2 1,78 2,0E-06 -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

HOXD8 Exerts a Tumor-Suppressing Role in Colorectal Cancer As an Apoptotic Inducer

HOXD8 exerts a tumor-suppressing role in colorectal cancer as an apoptotic inducer Mohammed A. Mansour1, Takeshi Senga2 1Biochemistry Division, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Tanta University, Tanta 31527, Egypt 2Division of Cancer Biology, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, 65 Tsurumai, Showa, Nagoya, 466-8550 Japan Address correspondence to: Mohammed A. Mansour; Biochemistry division, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Tanta University, Tanta 31527, Egypt; E-mail: [email protected] Running title: HOXD8 suppresses colorectal cancer progression Keywords: Colorectal Cancer; HOXD8; homology modeling; TCGA; STK38; MYC; Apoptosis Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The data sharing statement: No additional data are available. Abstract Homeobox (HOX) genes are conserved transcription factors which determine the anterior- posterior body axis patterning. HOXD8 is a member of HOX genes deregulated in several tumors such as lung carcinoma, neuroblastoma, glioma and colorectal cancer (CRC) in a context-dependent manner. In CRC, HOXD8 is downregulated in cancer tissues and metastatic foci as compared to normal tissues. Whether HOXD8 acts as a tumor suppressor of malignant progression and metastasis is still unclear. Also, the underlying mechanism of its function including the downstream targets is totally unknown. Here, we clarified the lower expression of HOXD8 in clinical colorectal cancer vs. normal colon tissues. Also, we showed that stable expression of HOXD8 in colorectal cancer cells significantly reduced the cell proliferation, anchorage-independent growth and invasion. Further, using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), we identified the genes associated with HOXD8 in order to demonstrate its function as a suppressor or a promoter of colorectal carcinoma. -

Chapter 2 Gene Regulation and Speciation in House Mice

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Gene regulation and the genomic basis of speciation and adaptation in house mice (Mus musculus) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8ck133qd Author Mack, Katya L Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Gene regulation and the genomic basis of speciation and adaptation in house mice (Mus musculus) By Katya L. Mack A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael W. Nachman, Chair Professor Rasmus Nielsen Professor Craig T. Miller Fall 2018 Abstract Gene regulation and the genomic basis of speciation and adaptation in house mice (Mus musculus) by Katya Mack Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology University of California, Berkeley Professor Michael W. Nachman, Chair Gene expression is a molecular phenotype that is essential to organismal form and fitness. However, how gene regulation evolves over evolutionary time and contributes to phenotypic differences within and between species is still not well understood. In my dissertation, I examined the role of gene regulation in adaptation and speciation in house mice (Mus musculus). In chapter 1, I reviewed theoretical models and empirical data on the role of gene regulation in the origin of new species. I discuss how regulatory divergence between species can result in hybrid dysfunction and point to areas that could benefit from future research. In chapter 2, I characterized regulatory divergence between M. -

Identification of Biomarkers of Metastatic Disease in Uveal

Identification of biomarkers of metastatic disease in uveal melanoma using proteomic analyses Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy Martina Angi June 2015 To Mario, the wind beneath my wings 2 Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge my primary supervisor, Prof. Sarah Coupland, for encouraging me to undergo a PhD and for supporting me in this long journey. I am truly grateful to Dr Helen Kalirai for being the person I could always turn to, for a word of advice on cell culture as much as on parenting skills. I would also like to acknowledge Prof. Bertil Damato for being an inspiration and a mentor; and Dr Sarah Lake and Dr Joseph Slupsky for their precious advice. I would like to thank Dawn, Haleh, Fidan and Fatima for becoming my family away from home, and the other members of the LOORG for the fruitful discussions and lovely cakes. I would like to acknowledge Prof. Heinrich Heimann and the clinical team at LOOC, especially Sisters Hebbar, Johnston, Hachuela and Kaye, for their admirable dedication to UM patients and for their invaluable support to clinical research. I would also like to thank the members of staff in St Paul’s theatre and Simon Biddolph and Anna Ikin in Pathology for their precious help in sample collection. I am grateful to Dr Rosalind Jenkins who guided my first steps in the mysterious word of proteomics, and to Dr Deb Simpsons and Prof. Rob Beynon for showing me its beauty. -

High-Resolution Mapping of a Genetic Locus Regulating Preferential Carbohydrate Intake, Total Kilocalories, and Food Volume on Mouse Chromosome 17

High-Resolution Mapping of a Genetic Locus Regulating Preferential Carbohydrate Intake, Total Kilocalories, and Food Volume on Mouse Chromosome 17 Rodrigo Gularte-Me´rida1¤, Lisa M. DiCarlo2, Ginger Robertson2, Jacob Simon2, William D. Johnson4, Claudia Kappen3, Juan F. Medrano1, Brenda K. Richards2* 1 Department of Animal Science, University of California Davis, Davis, California, United States of America, 2 Genetics of Eating Behavior Laboratory, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University System, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, United States of America, 3 Department of Developmental Biology, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University System, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, United States of America, 4 Biostatistics Department, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University System, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, United States of America Abstract The specific genes regulating the quantitative variation in macronutrient preference and food intake are virtually unknown. We fine mapped a previously identified mouse chromosome 17 region harboring quantitative trait loci (QTL) with large effects on preferential macronutrient intake-carbohydrate (Mnic1), total kilcalories (Kcal2), and total food volume (Tfv1) using interval-specific strains. These loci were isolated in the [C57BL/6J.CAST/EiJ-17.1-(D17Mit19-D17Mit50); B6.CAST-17.1] strain, possessing a ,40.1 Mb region of CAST DNA on the B6 genome. In a macronutrient selection paradigm, the B6.CAST-17.1 subcongenic mice eat 30% more calories from the carbohydrate-rich diet, ,10% more total calories, and ,9% more total food volume per body weight. In the current study, a cross between carbohydrate-preferring B6.CAST-17.1 and fat- preferring, inbred B6 mice was used to generate a subcongenic-derived F2 mapping population; genotypes were determined using a high-density, custom SNP panel. -

Article (Published Version)

Article A whole-genome association study of major determinants for host control of HIV-1 FELLAY, Jacques, et al. Abstract Understanding why some people establish and maintain effective control of HIV-1 and others do not is a priority in the effort to develop new treatments for HIV/AIDS. Using a whole-genome association strategy, we identified polymorphisms that explain nearly 15% of the variation among individuals in viral load during the asymptomatic set-point period of infection. One of these is found within an endogenous retroviral element and is associated with major histocompatibility allele human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B*5701, whereas a second is located near the HLA-C gene. An additional analysis of the time to HIV disease progression implicated two genes, one of which encodes an RNA polymerase I subunit. These findings emphasize the importance of studying human genetic variation as a guide to combating infectious agents. Reference FELLAY, Jacques, et al. A whole-genome association study of major determinants for host control of HIV-1. Science, 2007, vol. 317, no. 5840, p. 944-947 DOI : 10.1126/science.1143767 PMID : 17641165 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:9171 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Science. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2007 September 24. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: Science. 2007 August 17; 317(5840): 944±947. A Whole-Genome Association Study of Major Determinants for Host Control of HIV-1 Jacques Fellay1, Kevin V. -

Human Social Genomics in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis

Getting “Under the Skin”: Human Social Genomics in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis by Kristen Monét Brown A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Epidemiological Science) in the University of Michigan 2017 Doctoral Committee: Professor Ana V. Diez-Roux, Co-Chair, Drexel University Professor Sharon R. Kardia, Co-Chair Professor Bhramar Mukherjee Assistant Professor Belinda Needham Assistant Professor Jennifer A. Smith © Kristen Monét Brown, 2017 [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-9955-0568 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my grandmother, Gertrude Delores Hampton. Nanny, no one wanted to see me become “Dr. Brown” more than you. I know that you are standing over the bannister of heaven smiling and beaming with pride. I love you more than my words could ever fully express. ii Acknowledgements First, I give honor to God, who is the head of my life. Truly, without Him, none of this would be possible. Countless times throughout this doctoral journey I have relied my favorite scripture, “And we know that all things work together for good, to them that love God, to them who are called according to His purpose (Romans 8:28).” Secondly, I acknowledge my parents, James and Marilyn Brown. From an early age, you two instilled in me the value of education and have been my biggest cheerleaders throughout my entire life. I thank you for your unconditional love, encouragement, sacrifices, and support. I would not be here today without you. I truly thank God that out of the all of the people in the world that He could have chosen to be my parents, that He chose the two of you. -

Gene Regulation and the Genomic Basis of Speciation and Adaptation in House Mice (Mus Musculus)

Gene regulation and the genomic basis of speciation and adaptation in house mice (Mus musculus) By Katya L. Mack A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael W. Nachman, Chair Professor Rasmus Nielsen Professor Craig T. Miller Fall 2018 Abstract Gene regulation and the genomic basis of speciation and adaptation in house mice (Mus musculus) by Katya Mack Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology University of California, Berkeley Professor Michael W. Nachman, Chair Gene expression is a molecular phenotype that is essential to organismal form and fitness. However, how gene regulation evolves over evolutionary time and contributes to phenotypic differences within and between species is still not well understood. In my dissertation, I examined the role of gene regulation in adaptation and speciation in house mice (Mus musculus). In chapter 1, I reviewed theoretical models and empirical data on the role of gene regulation in the origin of new species. I discuss how regulatory divergence between species can result in hybrid dysfunction and point to areas that could benefit from future research. In chapter 2, I characterized regulatory divergence between M. m. domesticus and M. m. musculus associated with male hybrid sterility. The major model for the evolution of post-zygotic isolation proposes that hybrid sterility or inviability will evolve as a product of deleterious interactions (i.e., negative epistasis) between alleles at different loci when joined together in hybrids. As the regulation of gene expression is inherently based on interactions between loci, disruption of gene regulation in hybrids may be a common mechanism for post-zygotic isolation.