Jones V. Hayman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CH 12 Contempt of Court

CONTEMPT OF COURT .............................................................................. 1 §12-1 General Rules .............................................................................................. 1 §12-2 Direct Contempt and Indirect Contempt ............................................. 4 §12-3 Conduct of Counsel and Pro Se Litigant .............................................. 9 §12-4 Violating Court Orders ........................................................................... 14 §12-5 Other Conduct .......................................................................................... 17 §12-6 Sentencing ................................................................................................. 19 i CONTEMPT OF COURT §12-1 General Rules United States Supreme Court Codispoti v. Pennsylvania, 418 U.S. 506, 94 S.Ct. 2687, 41 L.Ed.2d 912 (1974) An alleged contemnor may be summarily tried for acts of contempt that occur during a trial, and may receive a sentence of no more than six months. In addition, the judge may summarily convict and punish for separate contemptuous acts that occur during trial even though the aggregate punishment exceeds six months. However, when a judge postpones until after trial contempt proceedings for various acts of contempt committed during trial, the contemnor is entitled to a jury trial if the aggregate sentence is more than six months, even though each individual act of contempt is punished by a term of less than six months. Gelbard v. U.S., 408 U.S. 41, 92 S.Ct. 2357, 33 L.Ed.2d 179 (1972) In defense to a contempt charge brought on the basis of a grand jury witness's refusal to obey government orders to testify before the grand jury, witness may invoke federal statute barring use of intercepted wire communications as evidence. Groppe v. Leslie, 404 U.S. 496, 92 S.Ct. 582, 30 L.Ed.2d 632 (1972) Due process was violated where, without notice or opportunity to be heard, state legislature passed resolution citing person for contempt that occurred two days earlier. -

The Historical Origins of the Sanction of Imprisonment for Serious Crime

Reprinted for private circulation from THE JOURNAL OF LEGAL STUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LAW SCHOOL Volume V (1) January 1976 PRINTED IN U.S.A. THE HISTORICAL ORIGINS OF THE SANCTION OF IMPRISONMENT FOR SERIOUS CRIME JOHN H. LANGBEIN. T HE.movement for the abolition of capital punishment is righty associ~ted with the writers of the Enlightenment, especially Beccaria, whose enormously influential tract appeared in 1764. Perhaps because the abolitionists drew so much attention to the gore of the capital sanctions of the eighteenth century, it has seldom been realized that capital punishment was already in a deep decline in the age of Beccaria and Voltaire. Writing to Voltaire in 1777, Frederick the Great boasted that in the whole Prussian realm executions had been occurring at the rate of only 14 or 15 per year.1 When John Howard visited Bremen in 1778 he discovered that "[t]here has been no execution in this city for twenty-six years."2 The abolition movement that we associate with Beccaria and Voltaire3 was a second-stage affair. Indeed, it had to be. For abolition presupposes the existence of a workable alternative for the punishment of serious crime. By the time of the American Revolution, the sanction of imprisonment for serious crime was in use throughout Europe, and England had developed a near equivalent. Although it is commonly said that "[t]he history of im prisonment has often been told,"4 Americans have not listened with much care. The claim is incessantly made that "[p]risons . , . are a pervasive American export, like tobacco in their international acceptance and perhaps • Professor of Law, University of Chicago. -

Crime, Sanctions and Scientific Explanation Thomas Orsagh

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 64 | Issue 3 Article 10 1974 Crime, Sanctions and Scientific Explanation Thomas Orsagh Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Thomas Orsagh, Crime, Sanctions and Scientific Explanation, 64 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 354 (1973) This Criminology is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE JOURNAL OP CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 64, No. 3 Copyright @ 1973 by Northwestern University School of Law Printed in U.S.A. CRIME, SANCTIONS AND SCIENTIFIC EXPLANATION THOMAS ORSAGH* There is no dearth of theoretical and empirical of the Crime-Sanctions (C-S) relation has been literature dealing with the relation between crime incorrect. and sanctions. In the last decade, interest in It is generally accepted that the relation of the subject seems to have quickened, no doubt crime to sanctions is likely to be quite complex. prompted to some extent by a well advertised and Current theory and empirical research suggest substantial rise in rates of reported crime. Recent that the two variables probably interact with each legalistic developments,1 because of their presumed other and with any number of other variables. But influence on crime rates, have also heightened our knowing this is one thing, coping with it something interest in the subject. -

Sanctions and Efficacy in Analytic Jurisprudence Brenner M

Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship 2017 Sanctions and Efficacy in Analytic Jurisprudence Brenner M. Fissell Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Brenner M. Fissell, Sanctions and Efficacy in Analytic Jurisprudence, 69 Rutgers L. Rev. 1627 (2017) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship/1209 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SANCTIONS AND EFFICACY IN ANALYTIC JURISPRUDENCE Brenner M. Fissell* ABSTRACT Legal theory has long grappled with the question of what features a rule system must have for it to be considered '7aw." Over time, a consensus has emerged that might seem counterintuitive to most people: a legal system does not require punishment for the disobedience of its rules (sanctions"), nor must it be obeyed by the people it purports to apply to (it need not have "efficacy'). In this Article, I do not challenge these conclusions, but instead stake out an attempt to reconcile these claims with other intuitions about law. I argue that while neither sanctions nor efficacy are alone determinative of legal validity, legal systems must at least aspire to be efficacious. Sanctions, then, may be seen as but one optional manifestation of the crucial background quality they represent: a readiness to adapt and react to the external realities surrounding a legal system's attempted implementation. -

Frivolous and Bad Faith Claims: Defense Strategies in Employment Litigation

Frivolous and Bad Faith Claims: Defense Strategies in Employment Litigation A Lexis Practice Advisor® Practice Note by Ellen V. Holloman and Jaclyn A. Hall, Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft, LLP Ellen Holloman Jaclyn Hall This practice note provides guidance on defending frivolous and bad faith claims in employment actions. While this practice note generally covers federal employment law claims, many of the strategies discussed below also apply to state employment law claims. When handling employment law claims in state court be sure to check the applicable state laws and rules. This practice note specifically addresses the following key issues concerning frivolous and bad faith claims in employment litigation: ● Determining If a Claim Is Frivolous or in Bad Faith ● Motion Practice against Frivolous Lawsuits ● Additional Strategies Available against Serial Frivolous Filers ● Alternative Dispute Resolution ● Settlement ● Attorney’s Fees and Costs ● Dealing with Frivolous Appeals Be mindful that frivolous and bad faith claims present particular challenges. On the one hand, if an employee lawsuit becomes public, there is a risk of reputational harm and damage even where the allegations are clearly unfounded. On the other hand, employers that wish to quickly settle employee complaints regardless of the lack of merit of the underlying allegations to avoid litigation can unwittingly be creating an incentive for other employees to file similar suits. Even claims that are on their face patently frivolous and completely lacking in evidentiary support will incur legal fees to defend. Finally, an award of sanctions and damages could be a Pyrrhic victory if a bad-faith plaintiff does not have the resources to pay. -

How to Use Structured Fines (Day Fines) As an Intermediate Sanction

T O EN F J U.S. Department of Justice TM U R ST A I P C E E D B O J Office of Justice Programs C S F A V M F O I N A C I J S R E BJ G O OJJ DP O F PR Bureau of Justice Assistance JUSTICE Bureau of Justice Assistance How To Use Structured Fines (Day Fines) as an Intermediate Sanction Monograph Bureau of Justice Assistance How To Use Structured Fines (Day Fines) as an Intermediate Sanction November 1996 Monograph NCJ 156242 This document was prepared by The Justice Management Institute and the Vera Institute of Justice, supported by grant number 91–DD–CX–0016(S–2), awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. © Vera Institute of Justice 1996. All rights reserved. Bureau of Justice Assistance 633 Indiana Avenue NW., Washington, DC 20531 U.S. Department of Justice Response Center 1–800–421–6770 Bureau of Justice Assistance Clearinghouse 1–800–688–4252 Bureau of Justice Assistance Internet Address http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/BJA The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, and the Office for Victims of Crime. -

Legal Sanctions Jerome Hall Indiana University School of Law

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Indiana University Bloomington Maurer School of Law Maurer School of Law: Indiana University Digital Repository @ Maurer Law Articles by Maurer Faculty Faculty Scholarship 1961 Legal Sanctions Jerome Hall Indiana University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, Legal History Commons, and the Natural Law Commons Recommended Citation Hall, Jerome, "Legal Sanctions" (1961). Articles by Maurer Faculty. Paper 1440. http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub/1440 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by Maurer Faculty by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LEGAL SANCTIONS* Modern legal systems employ a vast array of sanctions, and many precise distinctions regarding them are elucidated in the literature of jurisprudence which may be profitably employed in the analysis of the problems of organized coercion in the contemporary world. It is commonly assumed, however, that legal sanctions are technical, and this results not only in the neglect of the abundant data of legal institutions but also in the unsound bifurcation of social and legal research. Accordingly, the directions taken in this paper will be (1) to show that legal sanctions do not differ substantively from the sanc- tions of subgroups, (2) to mark out a unified field of sanctions-data in the more precise and significant terms that become available when relevant legal distinctions and the perspective of integrative jurisprudence are employed, and (3) to indicate some pertinent ethical problems. -

LAW FIRM SANCTIONS UNDER 28 USC § 1927 and the STRAINED READING of “PERSON” the Nightmare

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW LAW FIRMS ARE PEOPLE, TOO? LAW FIRM SANCTIONS UNDER 28 U.S.C. § 1927 AND THE STRAINED READING OF “PERSON” INTRODUCTION The nightmare scenario for any potential litigant is filing a slam-dunk lawsuit and, instead of moving seamlessly toward trial, spending years responding to motions and discovery requests, ultimately settling for pennies on the dollar.1 This is a familiar scenario, as parties often settle lawsuits for reasons unrelated to the merits of a case or the likely verdict. Forcing an opponent to respond to unnecessary filings can make the decision to settle hinge on a party’s ability and willingness to pay ever-increasing litigation costs.2 Indeed, it is relatively inexpensive to draft a bloated complaint or unnecessary discovery requests but often extremely costly for an opponent to respond.3 Although filing unnecessary motions can damage a litigant’s credibility,4 one attorney’s “diligent” litigation strategy and another attorney’s “unethical” abuse of judicial process may have the same practical effect in 1. See Jonathan T. Molot, How Changes in the Legal Profession Reflect Changes in Civil Procedure, 84 VA. L. REV. 955, 997 (1998) (“[A]ttorneys report that the time they devote to a case will depend more upon the events of that case—e.g., the extent of discovery and motion practice—than upon the case’s characteristics—e.g., stakes and complexity.”). 2. A related but separate issue is the filing of frivolous lawsuits, which needlessly inflict the costs of responding even if a case is eventually dismissed. -

Case 3:07-Cv-01188-D Document 365 Filed 12/11/08 Page 1 of 14 Pageid 7469

Case 3:07-cv-01188-D Document 365 Filed 12/11/08 Page 1 of 14 PageID 7469 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS DALLAS DIVISION SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE § COMMISSION, § § Plaintiff, § § Civil Action No. 3:07-CV-1188-D VS. § § AMERIFIRST FUNDING, INC., § et al., § § Defendants. § MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER The court-appointed temporary receiver (“Receiver”) has filed a September 9, 2008 notice of contemnors’ failure to comply with court order and request for detainment. The notice and request arise from the failure of three contemnors——one party and two nonparties——to pay the Receiver’s attorney’s fees and costs incurred in prosecuting a contempt motion, as this court required in an August 7, 2008 memorandum opinion and order (the “Fee Order”). See SEC v. AmeriFirst Funding, Inc., 2008 WL 3260376 (N.D. Tex. Aug. 7, 2008) (Fitzwater, C.J.). The Receiver requests that contemnors be detained until they comply with the Fee Order. For the reasons explained, the court holds that the Receiver must proceed through the contempt process and that a hearing is required before contemnors can be detained. The court therefore denies the Receiver’s request for detainment. If the Receiver has reasonable cause to believe that contemnors can pay the attorney’s fees and costs awarded, he may move the court to issue an order directing Case 3:07-cv-01188-D Document 365 Filed 12/11/08 Page 2 of 14 PageID 7470 that contemnors show cause why they should not be held in contempt for failing to comply with the Fee Order. -

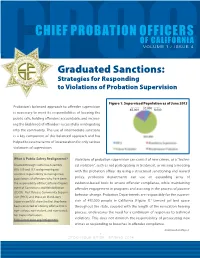

Graduated Sanctions: Strategies for Responding to Violations of Probation Supervision

VOLUME 1 / ISSUE 4 Graduated Sanctions: Strategies for Responding to Violations of Probation Supervision Figure 1: Supervised Population as of June 2013 Probation’s balanced approach to oender supervision 65,000 32,000 8,000 is necessary to meet its responsibilities of keeping the public safe, holding oenders accountable, and increas- ing the likelihood of oenders successfully reintegrating into the community. The use of intermediate sanctions is a key component of this balanced approach and has helped to reserve terms of incarceration for only serious violations of supervision. What is Public Safety Realignment? Violations of probation supervision can consist of new crimes, or a “techni- Enacted through California Assembly cal violation”, such as not participating in treatment, or missing a meeting Bills 109 and 117, realignment gave with the probation ocer. By using a structured sanctioning and reward counties responsibility to manage two populations of oenders who have been policy, probation departments can use an expanding array of the responsibility of the California Depart- evidence-based tools to ensure oender compliance, while maintaining ment of Corrections and Rehabilitation oender engagement in programs and assisting in the process of positive (CDCR). Post Release Community Supervi- behavior change. Probation Departments are responsible for the supervi- sion (PRCS) and those on Mandatory 1 Supervision(MS) share the fact they have sion of 413,000 people in California (Figure 1). Limited jail bed space been convicted of a felony oense that is throughout the state, coupled with the length of the revocation hearing non-serious, non-violent, and non-sexual. process, underscores the need for a continuum of responses to technical For more information, http://www.cpoc.org/realignment violations. -

Sanctions Under Criminal Law Criminal Law Aims to Protect Society

112 ACCESS AND JUSTICE However, Jessica may not receive any of the compensation awarded by the judge against the serial rapist. The County Court was told Victoria Legal Aid (VLA) had a caveat over Forde’s only asset, a block of land, to secure the cost of his legal representation. Jessica has asked VLA to waive their legal costs. Jessica’s lawyers stated that if the issue could not be resolved, legal avenues would be explored to establish whose claim took precedence. The maximum total payment to victims by the Victims of Crime Assistance Tribunal is $60 000, which is intended to cover loss of earnings, medical and counselling expenses and special fi nancial assistance for pain and suffering. Jessica fi ghts on for compensation Sanctions under criminal law Criminal law aims to protect society. In order that society can keep functioning, it is necessary for those who break the law to be dealt with through the courts. The government is responsible for maintaining an effective and effi cient legal system that deals fairly and justly with individuals who have broken the law. The offender has the right to be given a punishment appropriate to the crime committed. The victims or their families also have the right to see the offender punished for the harm they have done. However, it is possible that each person affected by the outcome will feel differently. An accused who has been found guilty but given a lenient sentence may feel that the outcome is just. The victim may disagree. After hearing all the evidence in a case, and deciding that the accused should be found guilty, the judge or magistrate will decide on a suitable punishment for the accused. -

Sanctions, Law and Public Order

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 1 Issue 3 Issue 3 - April 1948 Article 10 12-1947 Sanctions, Law and Public Order George H. Dession Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation George H. Dession, Sanctions, Law and Public Order, 1 Vanderbilt Law Review 8 (1948) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol1/iss3/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SANCTIONS, LAW AND PUBLIC ORDER GEORGE H. DESSION* A more creative conception of criminal law, and a more scientific and policy-minded approach to the organization of research, instruction and con- sultation concerning the use of criminal and other negative sanctions, 'have long been in making in the minds of many working in the field, in many widely separated places. My purpose in this paper is briefly to describe the kind of program currently conceived-to these ends in the Yale School of Law. Stemming from a series of exploratory studies and seminars conducted over the past few, years in collaboration with members of the Departments of Anthropology, Psychiatry and Public Health in the University, our pro- gram t is concerned with the technique of public order-that is to say, the "know-how" of the use of negative sanctions to preserve desired aspects of a culture or, as the case may be, to promote desired culture change.