Tom Brock Lecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Past Forward 37

Issue No. 37 July – November 2004 Produced1 by Wigan Heritage Service FREE From the Editor Retirement at the History Shop This edition of Past Forward reflects BARBARA MILLER, Heritage Assistant, manner. If she could not answer your the many exciting things which are retired on 6 June. It was a memorable query herself, she always knew going on in the Heritage Service at day for her. Not only was it the someone who could. the moment. There is an excellent beginning of a new and exciting stage Barbara joined the then Wigan exhibition programme for the rest of in her life, but also her 60th birthday (I Museum Service at Wigan Pier in 1985 the year, for example, as you will see am sure she will not mind that and, I am glad to say, remained with us – and our new exhibition leaflet will revelation!) and of course, she was a through our transformation into Wigan be out very soon. You can also read ‘D’ Day baby! Heritage Service and the development about the increasing range of Many of you will have met her on of the History Shop. In the past, she not the reception desk at the History Shop, only undertook a variety of clerical ventures in which our Friends have and been impressed by her duties for us, but also spent many been engaged. knowledgeable, friendly and efficient hours working on the museum I would draw your attention to collections, helping to make them more the questionnaire which appears in accessible. this issue – designed as a pull-out On her last day at work, we all had insert, as I know many of you a good laugh reminiscing about old treasure your copies of Past Forward, times. -

RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 1

rfl official guide 2012 working.e$S:RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 1 RFL Official Guide 201 2 rfl official guide 2012 working.e$S:RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 2 The text of this publication is printed on 100gsm Cyclus 100% recycled paper rfl official guide 2012 working.e$S:RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 1 CONTENTS Contents RFL B COMPETITIONS Index ........................................................... 02 B1 General Competition Rules .................. 154 RFL Directors & Presidents ........................... 10 B2 Match Day Rules ................................ 163 RFL Offices .................................................. 10 B3 League Competition Rules .................. 166 RFL Executive Management Team ................. 11 B4 Challenge Cup Competition Rules ........ 173 RFL Council Members .................................. 12 B5 Championship Cup Competition Rules .. 182 Directors of Super League (Europe) Ltd, B6 International/Representative Community Board & RFL Charities ................ 13 Matches ............................................. 183 Past Life Vice Presidents .............................. 15 B7 Reserve & Academy Rules .................. 186 Past Chairmen of the Council ........................ 15 Past Presidents of the RFL ............................ 16 C PERSONNEL Life Members, Roll of Honour, The Mike Gregory C1 Players .............................................. 194 Spirit of Rugby League Award, Operational Rules C2 Club Officials ..................................... -

Tom Brock Lecture Booklet 7 – Roy Masters

7TH ANNUAL TOM BROCK LECTURE NSW LEAGUES’ CLUB • 21 September 2005 ‘The Great Fibro versus Silvertail Wars’ The svengali of Lidcombe (courtesy of Moir and the Sydney Morning Herald, 13 Sept. 1984). Mr Roy Masters 7TH ANNUAL TOM BROCK LECTURE NSW LEAGUES’ CLUB SYDNEY • 21 SEPTEMBER 2005 ‘The Great Fibro versus Silvertail Wars’ The svengali of Lidcombe (courtesy of Moir and the Sydney Morning Herald, 13 Sept. 1984). Mr Roy Masters Published in 2006 by the Tom Brock Bequest Committee on behalf of the Australian Society for Sports History © ASSH and the Tom Brock Bequest Committee This monograph is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. ISBN: Design & layout: UNSW Publishing & Printing Services Printer: Graphitype TOM BROCK BEQUEST The Tom Brock Bequest, given to the Australian Society for Sports History (ASSH) in 1997, con- sists of the Tom Brock Collection supported by an ongoing bequest. The Collection, housed at the University of New South Wales, includes manuscript material, newspaper clippings, books, photographs and videos on rugby league in particular and Australian sport in general. It represents the finest collection of rugby league material in Australia. ASSH has appointed a Committee to oversee the Bequest and to organise appropriate activities to support the Collection from its ongoing funds. Objectives: 1. To maintain the Tom Brock Collection. 2. To organise an annual scholarly lecture on the history of Australian rugby league. 3. To award an annual Tom Brock Scholarship to the value of $5,000. -

PDF Download

Huddersfield Local History Society Huddersfield Local History Society huddersfieldhistory.org.uk Journal No. 22 May 2011 The articles contained within this PDF document remain the copyright of the original authors (or their estates) and may not be reproduced further without their express permission. This PDF file remains the copyright of the Society. You are free to share this PDF document under the following conditions: 1. You may not sell the document or in any other way benefit financially from sharing it 2. You may not disassemble or otherwise alter the document in any way (including the removal of this cover sheet) 3. If you make the file available on a web site or share it via an email, you should include a link to the Society’s web site JournalJournal HuddersfieldHuddersfield LocalLocal History History SocietySociety MayMay 2011 2011 IssueIssue No: No: 22 22 128919.indd 1 26/04/2011 12:21:44 HUDDERSFIELD LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY was formed in 1977. It was established to HUDDERSFIELD LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY create a means by which peoples of all levels of experience could share their common interests in the history of Huddersfield and district. We recognise that WEBSITE: www.huddersfieldhistory.org.uk Huddersfield enjoys a rich historical heritage. It is the home town of prime ministers Email address: [email protected] and Hollywood stars; the birthplace of Rugby League and famous Olympic athletes; it has more buildings than Bath listed for historical or architectural interest; it had the SOCIETY OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE first municipal trams and some of the first council housing; its radical heritage includes the Luddites, suffragettes, pacifists and other campaigners for change. -

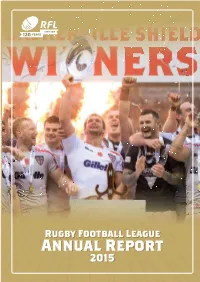

Annual Report

2015 RFL ANNUAL REPORT 2015 RFL ANNUAL RugbyRugby FootballFootball LeagueLeague AnnualAnnual ReportReport 20152015 RFL ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2015 CEO’s Review 4-6 Further Education 29 Chairman’s View 7 Schools 30-31 Board of Directors 8-9 Rugby League Cares 32-34 120 Years 10 Play Touch RL 35 Wembley Statue 11 Concussion 36 Magic Weekend 12 Cardiac Screening 37 World Club Series 13 Player Welfare 38-40 England Review 14-15 Hall of Fame 42 THE RUGBY Domestic Season Review 16-23 Safeguarding 43 FOOTBALL LEAGUE Events Review 24-25 RLEF Review 44-45 Red Hall, Red Hall Lane, Leeds, LS17 8NB Commercial Review 26-27 Operational Plan 46-47 T: 0844 477 7113 Higher Education 28 Financial Review 48-50 www.therfl .co.uk 3 The protocol on concussion was also CHIEF EXECUTIVE updated. Players suffering a suspected concussion during a game now have to undergo a proper assessment off the fi eld, with a free interchange allowed. The sport also mourned the passing OFFICER’S REPORT of Super League Match Offi cial Chris The year 2015 represented the 120th anniversary of the This secured their second trophy of the season, having already Leatherbarrow, a talented individual who creation of the sport of Rugby League and as was fi tting for this lifted the Ladbrokes Challenge Cup with a comprehensive win over tragically died at such a young age. momentous occasion, a number of celebratory events took place Hull Kingston Rovers at Wembley. A memorable treble beckoned to appropriately acknowledge this milestone. One of the biggest and it proved to be a nailbiting climax to the season when they VIEWERS AND was the Founders Walk, a 120-mile trek which took in each of the faced Wigan Warriors in the First Utility Grand Final. -

The All Golds and the Advent of Rugby League in Australasia

"ALL THAT GLITTERS" THE ALL GOLDS AND THE ADVENT OF RUGBY LEAGUE IN AUSTRALASIA. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History in the University of Canterbury by Jo Smith This thesis is dedicated toMu.m&Dad University of Canterbury 1998 CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF PLATES 11 LIST OF TABLES Ill ABBREVIATIONS l1l ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS IV PREFACE V ABSTRACT Vil CHAPTER: I A WORKING-CLASS GAME: ORIGINS OF RUGBY LEAGUE IN ENGLAND I II AN ENTREPRENEURIAL VENTURE: GENESIS OF THEALL GOLDS 21 III A WORKING-CLASS REVOLT: IMPACT OF THE ALL GOLDS IN AUSTRALIA 49 IV CLASH OF THE CODES: THE ALL GOLDS. IN BRITAIN 67 V THE ALL GOLQS RETURN: FOUNDATIONS OF RUGBY LEAGUE IN AUSTRALASIA 99 CONCLUSION 125 APPENDICES 128 BIBLIOGRAPHY 154 ll LIST OF PLATES PLATES After page: Plate 1. Albert Henry Baskiville. 21 Plate 2. The New Zealand Professional Rugby Team in Sydney. 63 Plate 3. The New Zealand Professional Football Team 1907. 67 Plate 4. The 'All Blacks' Autographs. 67 Plate 5. The New Zealand Footballers. 68 Plate 6. 'All Blacks' First Practice at Headingley. 71 Plate 7. Follow Up The Kick For 'On Side'. 71 Plate 8. The New Zealand Footballers. 71 Plate 9. A Group At Leeds. 71 Plate 10. The 'All Blacks' Chanting Their War Cry At Huddersfield. 74 Plate 11. The 'All Blacks' Win At Huddersfield. 74 Plate 12. New Zealand's Struggle At Oldham. 78 Plate 13. Red Rose Better Than All Black. 80 Plate 14. New Zealand Lost The First Test. -

Players Register A-Z 1895-2016

WAKEFIELD TRINITY RLFC PLAYERS REGISTER A-Z 1895-2016 HERITAGE NUMBERS … The Story Initial Ideas Our initial ideas for the heritage numbers came about a couple of years ago (approx. 2012), after seeing the success of Queensland in Australia, with Warrington being the first English club to follow suit. Next Step Tremendous work had been carried out by a group of rugby league historians in the 1970s (RL Record Keepers’ Club) who pooled their knowledge, and attempted to record every game in the first one hundred years of rugby league (1895-1994). Trinity’s were completed and fortunately we acquired the records to every Trinity game, and players, since 1895 The First 100 Years The teams for the first one hundred years of Trinity’s rugby league days (1895-1994) were recorded and each new player to make his debut noted. On the very first game there were fifteen (numbers 1-15) and each debutant after this was given the subsequent number, in position order (full back, winger, centre etc.). This was checked, double-checked and triple checked. By 1994 we had found 1,060 names. The Next 20 Years … Part 1 The next twenty years, to the modern day, were a little more difficult but we researched the Trinity playing records through the excellent ‘Rothman’s Year Books’ written by the late Raymond Fletcher and David Howes. These books started in 1981 and finished in 1999. Again, each debutant was given the next heritage number The Next 20 Years … Part 2 After the ‘Rothmans’ books ceased publication we used the yearbooks published by ‘League Weekly’, which also noted every new player, signed throughout the season. -

Alan Clarkson

4TH ANNUAL LECTURE TOM BROCK LECTURE SOUTH SYDNEY LEAGUES CLUB, 22 August 2002 The Changing Face of Rugby League Mr Alan Clarkson OAM Sydney 4TH ANNUAL TOM BROCK LECTURE SOUTH SYDNEY LEAGUES CLUB, REDFERN 22 AUGUST 2002 The Changing Face of Rugby League Alan Clarkson OAM Sydney ISBN: 0 7334 1951 8 Published in 2003 by the Tom Brock Bequest Committee Australian Society for Sports History © Tom Brock Bequest Committee This monograph is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permit- ted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. ISBN: 0 7334 1951 8 Design & layout: UNSW Publishing & Printing Services (Ref: 26712) Printer: Graphitype TOM BROCK BEQUEST The Tom Brock Bequest, given to the Australian Society for Sports History (ASSH) in 1997, consists of the Tom Brock Collection supported by an ongoing bequest. The Collection, housed at The University of New South Wales, includes manuscript material, newspaper clippings, books, photographs and videos on rugby league in particular and Australian sport in general. It represents the finest collection of rugby league material in Australia. ASSH has appointed a Committee to oversee the Bequest and to organise appropriate activities to support the Collection from its ongoing funds. Objectives: 1. To maintain the Tom Brock Collection. 2. To organise an annual scholarly lecture on the history of Australian rugby league. 3. To award an annual Tom Brock Scholarship to the value of $5,000. 4. To undertake any other activities which may advance the serious study of rugby league. -

Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year from the Newsletter Team Merry Christmas and a Prosperous New Year from the Mad Butcher by Sir Peter Leitch

Sir Peter Leitch Club AT MT SMART STADIUM, HOME OF THE MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS 19th December 2016 Newsletter #153 Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year from the Newsletter Team Merry Christmas and a Prosperous New Year from the Mad Butcher By Sir Peter Leitch OULD YOU believe it, the final newsletter of the year –No 153. WI have to thank the team that puts it all together with me. We get it out every week, sometimes under some tough conditions, but we do it. The newsletter is a real labour of love. It’s done with great affection for the game of league and especially for our wonderful Vodafone Warriors. We do not claim it is the world’s slickest and most professional league newsletter, but I certainly doubt there is anything else like it anywhere on the planet. Consider our contributors, John Holloway – who herds cats to get them to do the tipping; our Aussie cor- respondent Barry Ross – who had an operation this week and still filed on time; the promising writer John Deaker; one of the foremost league writers New Zealand has produced in John Coffey; former Suburban Newspapers and Sunday Star-Times editor David Kemeys – who could moan for England, young Ben Francis from up North, who is almost like our apprentice; and Hayden, who puts it all together, and who was a just a schoolboy when we started, and is now at university. As we say, no one ever pays to put an ad in, and no one ever pays to get it. My biggest thanks goes to the readers. -

3.3 Pupil Resource Sheet.Pdf

Theme 3 Timeline Pupil Resource Sheet: A History of Huddersfield Giants Rugby League Football Club PART 1, 1864-1890: The Birth of the Club The club that was to become Huddersfield In 1870 three of the Huddersfield players Giants Rugby League Football Club was played for the Yorkshire county team and in founded in 1864. Its name at that time was 1872 the club started a second team. the Huddersfield Athletic Club. It was founded by athletes who were dismayed that their training headquarters, the Apollo Gymnasium, which had opened in 1850, was to be converted into the Gymnasium Theatre. On 27 January 1866 the Huddersfield Athletic Club played a ‘football’ match against the Huddersfield Rifle Corps at Rifle St John’s Gymnasium Field – roughly where Greenhead Park is In 1875 the Huddersfield Athletic Club today. This match would have appeared to opened a new building as its headquarters us as a strange mix of association and rugby and for indoor training, the St John’s football. The first rules of association Gymnasium in St John’s Road. The last football had been written in 1863 but the surviving piece of this building, the apex, first rules of rugby would not be written has been restored and forms the until 1871, and different versions of football centrepiece of the memorial garden at The were still played in different places. John Smith’s Stadium. The match was very popular and in December 1866 the Huddersfield Athletic Club started to run a football section. There weren’t many other teams to play against so they often played amongst themselves, but in 1869 they played six matches against teams from other places. -

RLWC 2017 18Th October 2017 It’S 10 Days Until the Kiwis Play Their First Game of the 2017 RLWC #192

Sir Peter Leitch Club Newsletter RLWC 2017 18th October 2017 It’s 10 days until the Kiwis play their first game of the 2017 RLWC #192 David’s Guide To The World Cup By David Kemeys Former Sunday Star-Times Editor, Former Editor-in-Chief Suburban Newspapers, Long Suffering Warriors Fan ’M GETTING excited as we inch closer to the 2017 Rugby League World Cup. ILike everyone, I can’t see anyone but Australia winning, although I have not given up on my Kiwis. Getting your head around the format is a bit of a head-scratcher, but being a self-appointed league genius, I have decided to simplify things for you. Three teams from Pool A and B go to the quarter-finals, but only the winners of Pool C and D do – giving you the eight teams you need, and eliminating six others. Pool A: Australia, England, France, Lebanon: The Kangaroos have seven players from Melbourne’s premier- ship-winning team, give or take, half the side. They start against England on October 27, and the only question is how they cope without Johnathan Thurs- ton, although they have Cameron Munster, James Maloney and Michael Morgan, so some pretty tasty players all round. They also have coach Mal Meninga. England will be looking for their first ever World Cup. They have reached the semis every time, but have nev- er gone all the way, so they will be desperate to make this year theirs. They have another super-coach in Wayne Bennett, but he has thrown up some strange selections, and the British press have certainly fallen out of love with him. -

Foundation Licensed Under Cover Driving Range Bar • Functions

ISSUE #77 2020 MEN OF CARING FOR THE MEN, WOMEN AND CHILDREN OF THE RUGBY LEAGUE COMMUNITY FOUNDATION LICENSED UNDER COVER DRIVING RANGE BAR • FUNCTIONS Aces Sporting Club • Springvale Rd & Hutton Rd, Keysborough Ph. 9701 5000 • acessportingclub.com.au • /AcesSportingClub LOOK FORWARD TO REOPENING SOON ✃ PRPREESENTSENT THISTHIS FFLLYEYERR ININ THE THE DRIVING DRIVING RANGE RANGE FOR FOR 200200 BBAALLLLSS FFOORR $$1100 SPOSPORRTTIINGNG CCLULUBB Can not be used in conjunction with any other offer. Terms and Conditions Apply. IN THIS FROM THE OUR COVER Introducing our newest board member Katrina Fanning and recently announced life member Tony Durkin. PROFESSOR THE INSIDE THIS ISSUE 5 McCloy Group corporate membership HONOURABLE 6 Tony Durkin 8 Lionel Morgan STEPHEN MARTIN 11 Katrina Fanning 14 Socially connecting As you read this message, the Foundation brings enormous experience to our board 16 Try July is still unfortunately greatly impacted by as a former Jillaroo, having played 26 Tests 17 Arthur Summons COVID-19 and the necessary restrictions that for Australia and held the roles of president 18 Keith Gee have been imposed by health and government of the Australian Women’s Rugby League 21 Mortimer Wines promotion authorities. Association, chairperson of the Australian 22 Noel Kelly Rugby League Indigenous Council and a 24 Champion Broncos 20 years on The Foundation itself remains in hibernation director of the board of the Canberra Raiders. 26 Ranji Joass mode. Most staff remain stood down, and Welcome Katrina! 34 Phillippa Wade and her Storm Sons we are fortunate that JobKeeper has been 28 Q/A with Peter Mortimer available to us.