Tales from Coathanger City – Ten Years of Tom Brock Lectures Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

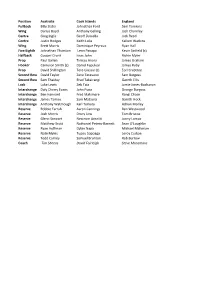

Position Australia Cook Islands England Fullback Billy Slater

Position Australia Cook Islands England Fullback Billy Slater Johnathan Ford Sam Tomkins Wing Darius Boyd Anthony Gelling Josh Charnley Centre Greg Inglis Geoff Daniella Jack Reed Centre Justin Hodges Keith Lulia Kallum Watkins Wing Brett Morris Dominique Peyroux Ryan Hall Five Eighth Johnathan Thurston Leon Panapa Kevin Sinfield (c) Halfback Cooper Cronk Issac John Richie Myler Prop Paul Gallen Tinirau Arona James Graham Hooker Cameron Smith (c) Daniel Fepuleai James Roby Prop David Shillington Tere Glassie (c) Eorl Crabtree Second Row David Taylor Zane Tetevano Sam Burgess Second Row Sam Thaiday Brad Takairangi Gareth Ellis Lock Luke Lewis Zeb Taia Jamie Jones-Buchanan Interchange Daly Cherry Evans John Puna George Burgess Interchange Ben Hannant Fred Makimare Rangi Chase Interchange James Tamou Sam Mataora Gareth Hock Interchange Anthony Watmough Karl Temata Adrian Morley Reserve Robbie Farrah Aaron Cannings Ben Westwood Reserve Josh Morris Drury Low Tom Briscoe Reserve Glenn Stewart Neccrom Areaiiti Jonny Lomax Reserve Matthew Scott Nathaniel Peteru-Barnett Sean O'Loughlin Reserve Ryan Hoffman Dylan Napa Michael Mcllorum Reserve Nate Myles Tupou Sopoaga Leroy Cudjoe Reserve Todd Carney Samuel Brunton Rob Burrow Coach Tim Sheens David Fairleigh Steve Mcnamara Fiji France Ireland Italy Jarryd Hayne Tony Gigot Greg McNally James Tedesco Lote Tuqiri Cyril Stacul John O’Donnell Anthony Minichello (c) Daryl Millard Clement Soubeyras Stuart Littler Dom Brunetta Wes Naiqama (c) Mathias Pala Joshua Toole Christophe Calegari Sisa Waqa Vincent -

TO: NZRL Staff, Districts and Affiliates and Board FROM: Cushla Dawson

TO: NZRL Staff, Districts and Affiliates and Board FROM: Cushla Dawson DATE: 28 October 2008 RE: Media Summary Wednesday 29 October to Monday 03 November 2008 Slater takes place among the greats: AUSTRALIA 52 ENGLAND 4. Billy Slater last night elevated himself into the pantheon of great Australian fullbacks with a blistering attacking performance that left his coach and Kangaroos legend Ricky Stuart grasping for adjectives. Along with Storm teammate and fellow three-try hero Greg Inglis, Slater turned on a once-in-a-season performance to shred England to pieces and leave any challenge to Australia's superiority in tatters. It also came just six days after the birth of his first child, a baby girl named Tyla Rose. Kiwis angry at grapple tackle: The Kiwis are fuming a dangerous grapple tackle on wing Sam Perrett went unpunished in last night's World Cup rugby league match but say they won't take the issue further. Wing Sam Perrett was left lying motionless after the second tackle of the match at Skilled Park, thanks to giant Papua New Guinea prop Makali Aizue. Replays clearly showed Aizue, the Kumuls' cult hero who plays for English club Hull KR, wrapping his arm around Perrett's neck and twisting it. Kiwis flog Kumuls: New Zealand 48 Papua New Guinea NG 6. A possible hamstring injury to Kiwis dynamo Benji Marshall threatened to overshadow his side's big win over Papua New Guinea at Skilled Park last night. Arguably the last superstar left in Stephen Kearney's squad, in the absence of show-stoppers like Roy Asotasi, Frank Pritchard and Sonny Bill Williams, Marshall is widely considered the Kiwis' great white hope. -

The Great Images of Rugby League Geoff Armstrong

photograph by John O’Gready/Fairfaxphotos ‘who’s ThaT?’ The greaT Images oF rUgby leagUe Geoff Armstrong If a ballot was taken for the best known photograph in Australian that would become known as The Gladiators made page 3, rugby league, there is little doubt that the remarkable image of alongside the news that the Lord Mayor of Sydney, Harry Norm Provan and Arthur Summons, taken by the Sun-Herald’s Jensen, had failed in his bid for preselection for the federal seat John O’Gready in the immediate aftermath of the 1963 Sydney of East Sydney. Ask most league fans today the names of the grand final, would claim the prize. The photo of two mud-clad, footballers in the photo and they’d know the answer. Back in exhausted warriors, one tall, one short — caught in a cheerful August 1963, the heading atop the Provan–Summons photo sporting embrace and lit by a shaft of sunlight that cut through asked, succinctly: ‘Who’s That?’ the murky gloom in the moments after an epic battle — would win international awards and famously be cast in bronze as Like so many things in sport, the immediate appeal of a rugby the Winfield Cup. In the process, it helped make Provan and league photograph is often in the eye of the beholder. It is hard Summons two of the best remembered players of their era. to imagine too many drenched Wests fans who’d been at the It seems a little strange then that the day after the grand final, 1963 grand final looking at The Gladiators too fondly; especially 25 August 1963, the editor of the Sun-Herald decided that if they knew that, at the precise moment O’Gready ‘hit the O’Gready’s photograph was not worthy of the front page. -

Past Forward 37

Issue No. 37 July – November 2004 Produced1 by Wigan Heritage Service FREE From the Editor Retirement at the History Shop This edition of Past Forward reflects BARBARA MILLER, Heritage Assistant, manner. If she could not answer your the many exciting things which are retired on 6 June. It was a memorable query herself, she always knew going on in the Heritage Service at day for her. Not only was it the someone who could. the moment. There is an excellent beginning of a new and exciting stage Barbara joined the then Wigan exhibition programme for the rest of in her life, but also her 60th birthday (I Museum Service at Wigan Pier in 1985 the year, for example, as you will see am sure she will not mind that and, I am glad to say, remained with us – and our new exhibition leaflet will revelation!) and of course, she was a through our transformation into Wigan be out very soon. You can also read ‘D’ Day baby! Heritage Service and the development about the increasing range of Many of you will have met her on of the History Shop. In the past, she not the reception desk at the History Shop, only undertook a variety of clerical ventures in which our Friends have and been impressed by her duties for us, but also spent many been engaged. knowledgeable, friendly and efficient hours working on the museum I would draw your attention to collections, helping to make them more the questionnaire which appears in accessible. this issue – designed as a pull-out On her last day at work, we all had insert, as I know many of you a good laugh reminiscing about old treasure your copies of Past Forward, times. -

THE 300 CLUB (39 Players)

THE 300 CLUB (39 players) App Player Club/s Years 423 Cameron Smith Melbourne 2002-2020 372 Cooper Cronk Melbourne, Sydney Roosters 2004-2019 355 Darren Lockyer Brisbane 1995-2011 350 Terry Lamb Western Suburbs, Canterbury 1980-1996 349 Steve Menzies Manly, Northern Eagles 1993-2008 348 Paul Gallen Cronulla 2001-2019 347 Corey Parker Brisbane 2001-2016 338 Chris Heighington Wests Tigers, Cronulla, Newcastle 2003-2018 336 Brad Fittler Penrith, Sydney Roosters 1989-2004 336 John Sutton South Sydney 2004-2019 332 Cliff Lyons North Sydney, Manly 1985-1999 330 Nathan Hindmarsh Parramatta 1998-2012 329 Darius Boyd Brisbane, St George Illawarra, Newcastle 2006-2020 328 Andrew Ettingshausen Cronulla 1983-2000 326 Ryan Hoffman Melbourne, Warriors 2003-2018 325 Geoff Gerard Parramatta, Manly, Penrith 1974-1989 324 Luke Lewis Penrith, Cronulla 2001-2018 323 Johnathan Thurston Bulldogs, North Queensland 2002-2018 323 Adam Blair Melbourne, Wests Tigers, Brisbane, Warriors 2006-2020 319 Billy Slater Melbourne 2003-2018 319 Gavin Cooper North Queensland, Gold Coast, Penrith 2006-2020 318 Jason Croker Canberra 1991-2006 317 Hazem El Masri Bulldogs 1996-2009 316 Benji Marshall Wests Tigers, St George Illawarra, Brisbane 2003-2020 315 Paul Langmack Canterbury, Western Suburbs, Eastern Suburbs 1983-1999 315 Luke Priddis Canberra, Brisbane, Penrith, St George Illawarra 1997-2010 313 Steve Price Bulldogs, Warriors 1994-2009 313 Brent Kite St George Illawarra, Manly, Penrith 2002-2015 311 Ruben Wiki Canberra, Warriors 1993-2008 309 Petero Civoniceva Brisbane, -

2Featherstone.Pdf

# LEYTHERS # OURTOWNOURCLUB# OURTOWNOURCLUB # LEYTHERS # OURTOWNOURCLUB# OURTOWNOURCLUB MIKEFROMWelcome to LSV forLATHAM this afternoon’s THEthe top threeCHAIRMAN away trips for manyTOP Leigh the Wheatsheaf in Atherton for hosting a Betfred Championship game fans and the home officials and coach team breakfast on the Saturday morning against Featherstone Rovers. Richard Marshall were full of praise for before the Toulouse game. This was a A lot of water has flowed under Mather Leigh’s display after the game. tremendous success as Duffs organised Lane bridge since the two sides met in the The Saints players that have represented many legendary former players to come Championship Shield Final in early the club so far have done so with along and present shirts to the current October and both sides will have a lot of distinction and the relationship between squad. new personnel on duty this afternoon. the two clubs has been excellent with the To hear the likes of Alex Murphy OBE, Games against Fev are always keenly dual registration system operating to the Kevin Ashcroft, Rod Tickle, Tony Barrow, fought and entertaining encounters and benefit of both parties. John Woods, Des Drummond, Mick this afternoon’s game should be no Jack Ashworth was sponsors’ man of the Stacey, Phil Fox, Tony Cooke, Timmy exception. Rovers had a good win against match after the Toulouse game and his Street, Dave Bradbury, Tommy Goulden Batley last Sunday after an agonising one- performances will see push for a first and Mark Sheals waxing lyrical about what point defeat against Bradford and with a team recall at Saints in the near future. -

RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 1

rfl official guide 2012 working.e$S:RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 1 RFL Official Guide 201 2 rfl official guide 2012 working.e$S:RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 2 The text of this publication is printed on 100gsm Cyclus 100% recycled paper rfl official guide 2012 working.e$S:RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 1 CONTENTS Contents RFL B COMPETITIONS Index ........................................................... 02 B1 General Competition Rules .................. 154 RFL Directors & Presidents ........................... 10 B2 Match Day Rules ................................ 163 RFL Offices .................................................. 10 B3 League Competition Rules .................. 166 RFL Executive Management Team ................. 11 B4 Challenge Cup Competition Rules ........ 173 RFL Council Members .................................. 12 B5 Championship Cup Competition Rules .. 182 Directors of Super League (Europe) Ltd, B6 International/Representative Community Board & RFL Charities ................ 13 Matches ............................................. 183 Past Life Vice Presidents .............................. 15 B7 Reserve & Academy Rules .................. 186 Past Chairmen of the Council ........................ 15 Past Presidents of the RFL ............................ 16 C PERSONNEL Life Members, Roll of Honour, The Mike Gregory C1 Players .............................................. 194 Spirit of Rugby League Award, Operational Rules C2 Club Officials ..................................... -

National Coaches Conference 2018 PROGRAM 2 NRL National Coaches Conference Program 2018 3 NRL National Coaches Conference Program 2018

National Coaches Conference 2018 PROGRAM 2 NRL National Coaches Conference Program 2018 3 NRL National Coaches Conference Program 2018 National Coaches Conference Program NRL Welcome 4 NRL National Coaches Conference Program 2018 National Coaches Conference Program NRL Welcome Luke Ellis Head of Participation, Pathways & Game Development Welcome to the 2018 NRL National Coaching Conference, the largest coach development event on the calendar. In the room, there are coaches working with our youngest participants right through to our development pathways and elite level players. Each of you play an equally significant role in the development and future of the players in your care, on and off the field. Over the weekend, you will get the opportunity to hear from some remarkable people who have made a career out of Rugby League and sport in general. I urge you to listen, learn, contribute and enjoy each of the workshops. You will also have a fantastic opportunity to network and share your knowledge with coaches from across the nation and overseas. Coaches are the major influencer on long- term participation and enjoyment of every player involved in Rugby League. As a coach, it is our job to create a positive environment where the players can have fun, enjoy time with their friends, develop their skills, and become better people. Coaches at every level of the game, should be aiming to improve the CONFIDENCE, CHARACTER, COMPETENCE and CONNECTIONS with our players. Remember… It’s not just what you coach… It’s HOW you coach. Enjoy the weekend, Luke Ellis 5 NRL National Coaches Conference Program 2018 National Coaches Conference Program NRL Andrew Voss Event MC Now referred to as a media veteran in rugby league circles, Andrew is a sport and news presenter, commentator, writer and author. -

21 September 2005

DEBATES OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FOR THE AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY SIXTH ASSEMBLY WEEKLY HANSARD 21 SEPTEMBER 2005 Wednesday, 21 September 2005 Limitation Amendment Bill 2005 ................................................................................3425 Civic Development Authority Bill 2005 ......................................................................3428 Legislation Amendment Bill 2005 ...............................................................................3431 Proposed motion on industrial relations laws...............................................................3434 Industrial relations ........................................................................................................3435 Questions without notice: Canberra Hospital—psychiatric unit ........................................................................3457 Disaster planning ......................................................................................................3458 Tree protection legislation........................................................................................3458 Vocational education and training............................................................................3461 Planning—delays......................................................................................................3462 Housing affordability................................................................................................3465 Sustainable transport plan.........................................................................................3466 -

4Th Annual Report for the Year Ended 31 October 2009

4TH ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2009 SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBERS RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL CLUB LTD ACN 118 320 684 ANNUAL REPORT YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2009 Just one finger. Contents Page 01 Chairman’s Report 3 02 100 Grade Games 4 03 Life Members 6 04 Financials 7 - Directors’ Report 7a, 7b - Lead Auditor’s Independence Declaration 7c - Income Statement - Statement of Recognised Income and Expense 7d - Balance Sheet - Statement of Cash Flow 7e - Discussion and Analysis - Notes to the Financial Statements 7f, 7g - Directors’ Declaration 7h - Audit Report 7h 05 Corporate Partners 8 06 South Sydney District Rugby League Football Club Limited 9 07 NRL Results Premiership Matches 2009 13 NRL Player Record for Season 2009 15 2009 NRL Ladder 15 08 NSW Cup Results 2009 16 09 Toyota Cup Results 2009 17 10 2009 Toyota Cup Ladder 18 The new ‘just one finger’ De–Longhi Primadonna Avant Fully Automatic coffee machine. 2009 Club Awards 18 You would be excited too, with De–Longhi’s range of ‘just one finger’ Fully Automatic Coffee Machines setting a new standard in coffee appreciation. Featuring one touch technology for barista quality Cappuccino, Latte or Flat White, all in the comfort of your own home. All models include automatic cleaning, an in-built quiet grinder and digital programming to personalise your coffee settings. With a comprehensive range to choose from, you’ll be spoilt for choice. www.delonghi.com.au / 1800 126 659 SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBERS RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL CLUB LIMITED 1 ANNUAL REPORT YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2009 Chairman’s Report 01 My report to Members last year was written In terms of financial performance, I am pleased each of them for the commitment they have on the eve of our return to a renovated and to report that the 2009 year delivered the shown in ensuring that Members’ rights are remodelled Redfern Oval. -

TO: NZRL Staff, Districts and Affiliates and Board FROM: Cushla Dawson

TO: NZRL Staff, Districts and Affiliates and Board FROM: Cushla Dawson DATE: 23 February 2009 RE: Media Summary Tuesday 17 February to Monday 23 February 2009 Hewitt now heads Taranaki Rugby League Academy: A man who survived three days in the sea off the Kapiti Coast is warming to a new challenge. Waatea News reports Rob Hewitt has taken over the reins of the Taranaki Rugby League Academy. The former navy diver says sport is a way to get students thinking about their futures and to learn how to be successful on and off the field. However, he says, he was nervous at the start and "wanted out" two weeks ago. But now he's settled in. Hewitt will also continue his work as an ambassador for Water Safety New Zealand. Source: Radio New Zealand, 23 February 2009 Mannering keeps captain ambitions private: SIMON Mannering is refusing to buy into suggestions linking him to the future captaincy of the Warriors. Mannering's decision as revealed in last week's Sunday News to re-sign with the club despite the likelihood of making more money overseas, has prompted speculation that the loyal utility is a "captain in the making". His leadership potential is clear with Kiwis coach Stephen Kearney just last week heaping praise on him. Where did all the NZRL's money go?: Like any gambler, rugby league played the pokies, and at first, they got a few decent payouts. Encouraged, they hit the button one more time, and lost the lot. The unholy pairing of pubs and poker machines is the big reason rugby league found itself in such deep trouble that Sparc thumped in and demanded last week's damning Anderson Report, which called those sordid dealings a "sorry chapter" in the game's history, and declared: "This matter should now be regarded as a lesson learnt, and the sport should move on." Bennett tipped to return as Kangaroos coach after leaving Kiwis: WAYNE BENNETT'S odds of taking over as Kangaroos coach have been slashed after he stepped down yesterday from his role with New Zealand. -

Sir Peter Leitch Club at MT SMART STADIUM, HOME of the MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS

Sir Peter Leitch Club AT MT SMART STADIUM, HOME OF THE MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS 27th July 2016 Newsletter #132 Parker v Haumono Photos courtesy of www.photosport.nz At the Parker Fight in Christchurch Great to catch up with the legend Me and Butterbean who is doing Kevin Barry giving Mike Morton Monty Betham at the boxing. Monty some fantastic work in the communi- from the Mad Butcher some stick left on Tuesday for the Rio Olympics ty. Very proud of this boy. after Mike won the meat raffle in as part of Sky TV’s team. Top man! the pub (no it was not mad butcher meat). Me and my mate Dexter ready to rock My grandson Matthew caught up The boys ready to hit the town in the night away in Christchurch. with Joseph Parker after his win in Christchurch. Nino, Rodney, Butch Christchurch. and Daniel. Was great to catch up with my old mate, international boxing com- mentator, Colonel Bob Sheridan. Bob is based in Las Vegas and has called over 10,000 fights including Muhammed Ali, George Foreman and Larry Holmes to name a few. He has been inducted into the boxing Hall of Fame and is a top bloke. Also at the boxing 3 former Kiwis Logan Edwards, Justin Wallace, Mark Woods. Hi all Feel free to share this coverage with your friends & ust wanted to give you a heads up on the feature community .. that screened yesterday on The Hui (TV3) about J the NZRL Taurahere camp on the Gold Coast this Watch full feature here month.