Rifts in Time and Space: Playing with Time in Barker, Stoppard, and Churchill Jay M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plays to Read for Furman Theatre Arts Majors

1 PLAYS TO READ FOR FURMAN THEATRE ARTS MAJORS Aeschylus Agamemnon Greek 458 BCE Euripides Medea Greek 431 BCE Sophocles Oedipus Rex Greek 429 BCE Aristophanes Lysistrata Greek 411 BCE Terence The Brothers Roman 160 BCE Kan-ami Matsukaze Japanese c 1300 anonymous Everyman Medieval 1495 Wakefield master The Second Shepherds' Play Medieval c 1500 Shakespeare, William Hamlet Elizabethan 1599 Shakespeare, William Twelfth Night Elizabethan 1601 Marlowe, Christopher Doctor Faustus Jacobean 1604 Jonson, Ben Volpone Jacobean 1606 Webster, John The Duchess of Malfi Jacobean 1612 Calderon, Pedro Life is a Dream Spanish Golden Age 1635 Moliere Tartuffe French Neoclassicism 1664 Wycherley, William The Country Wife Restoration 1675 Racine, Jean Baptiste Phedra French Neoclassicism 1677 Centlivre, Susanna A Bold Stroke for a Wife English 18th century 1717 Goldoni, Carlo The Servant of Two Masters Italian 18th century 1753 Gogol, Nikolai The Inspector General Russian 1842 Ibsen, Henrik A Doll's House Modern 1879 Strindberg, August Miss Julie Modern 1888 Shaw, George Bernard Mrs. Warren's Profession Modern Irish 1893 Wilde, Oscar The Importance of Being Earnest Modern Irish 1895 Chekhov, Anton The Cherry Orchard Russian 1904 Pirandello, Luigi Six Characters in Search of an Author Italian 20th century 1921 Wilder, Thorton Our Town Modern 1938 Brecht, Bertolt Mother Courage and Her Children Epic Theatre 1939 Rodgers, Richard & Oscar Hammerstein Oklahoma! Musical 1943 Sartre, Jean-Paul No Exit Anti-realism 1944 Williams, Tennessee The Glass Menagerie Modern -

Objects in Tom Stoppard's Arcadia

Cercles 22 (2012) ANIMAL, VEGETABLE OR MINERAL? OBJECTS IN TOM STOPPARD’S ARCADIA SUSAN BLATTÈS Université Stendhal—Grenoble 3 The simplicity of the single set in Arcadia1 with its rather austere furniture, bare floor and uncurtained windows has been pointed out by critics, notably in comparison with some of Stoppard’s earlier work. This relatively timeless set provides, on one level, an unchanging backdrop for the play’s multiple complexities in terms of plot, ideas and temporal structure. However we should not conclude that the set plays a secondary role in the play since the mysteries at the centre of the plot can only be solved here and with this particular group of characters. Furthermore, I would like to suggest that the on-stage objects play a similarly vital role by gradually transforming our first impressions and contributing to the multi-layered meaning of the play. In his study on the theatre from a phenomenological perspective, Bert O. States writes: “Theater is the medium, par excellence, that consumes the real in its realest forms […] Its permanent spectacle is the parade of objects and processes in transit from environment to imagery” [STATES 1985 : 40]. This paper will look at some of the parading or paraded objects in Arcadia. The objects are many and various, as can be seen in the list provided in the Samuel French acting edition (along with lists of lighting and sound effects). We will see that there are not only many different objects, but also that each object can be called upon to assume different functions at different moments, hence the rather playful question in the title of this paper (an allusion to the popular game “Twenty Questions” in which the identity of an object has to be guessed), suggesting we consider the objects as a kind of challenge to the spectator, who is set the task of identifying and interpreting them. -

Past Productions

Past Productions 2017-18 2012-2013 2008-2009 A Doll’s House Born Yesterday The History Boys Robert Frost: This Verse Sleuth Deathtrap Business Peter Pan Les Misérables Disney’s The Little The Importance of Being The Year of Magical Mermaid Earnest Thinking Only Yesterday Race Laughter on the 23rd Disgraced No Sex Please, We're Floor Noises Off British The Glass Menagerie Nunsense Take Two 2016-17 Macbeth 2011-2012 2007-2008 A Christmas Carol Romeo and Juliet How the Other Half Trick or Treat Boeing-Boeing Loves Red Hot Lovers Annie Doubt Grounded Les Liaisons Beauty & the Beast Mamma Mia! Dangereuses The Price M. Butterfly Driving Miss Daisy 2015-16 Red The Elephant Man Our Town Chicago The Full Monty Mary Poppins Mad Love 2010-2011 2006-2007 Hound of the Amadeus Moon Over Buffalo Baskervilles The 39 Steps I Am My Own Wife The Mountaintop The Wizard of Oz Cats Living Together The Search for Signs of Dancing At Lughnasa Intelligent Life in the The Crucible 2014-15 Universe A Chorus Line A Christmas Carol The Real Thing Mid-Life! The Crisis Blithe Spirit The Rainmaker Musical Clybourne Park Evita Into the Woods 2005-2006 Orwell In America 2009-2010 Lend Me A Tenor Songs for a New World Hamlet A Number Parallel Lives Guys And Dolls 2013-14 The 25th Annual I Love You, You're Twelve Angry Men Putnam County Perfect, Now Change God of Carnage Spelling Bee The Lion in Winter White Christmas I Hate Hamlet Of Mice and Men Fox on the Fairway Damascus Cabaret Good People A Walk in the Woods Spitfire Grill Greater Tuna Past Productions 2004-2005 2000-2001 -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Park-Finch, Heebon Title: Hypertextuality and polyphony in Tom Stoppard's stage plays General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. Hypertextuality and Polyphony in Tom Stoppard's Stage Plays Heebon Park-Finch A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in -

The Pillowman

THE PILLOWMAN Company B presents THE PILLOWMAN Written by MARTIN McDONAGH Directed by CRAIG ILOTT The Company B production of The Pillowman opened at Belvoir St Theatre on 4 June 2008 Set Designer NICHOLAS DARE Costume Designer JO BRISCOE Lighting Designer NIKLAS PAJANTI Composer & Sound Designer JETHRO WOODWARD Assistant Sound Designer CHRIS MERCER Fight Director KYLE ROWLING Stage Manager KYLIE MASCORD Assistant Stage Manager SARAH SMITH NIDA Secondment (Stage Management) ISABELLA KERDIJK NIDA Secondment (Technical) JACK HORTON Consultant Clinical Psychologist DR RACHAEL MURRIHY (BA PGDip DPsych) With AMANDA BISHOP Mother MARTON CSOKAS Tupolski LAUREN ELTON Girl DAMON HERRIMAN Katurian STEVE RODGERS Michal DAVID TERRY Father DAN WYLLIE Ariel PRODUCTION THANKS: Chameleon Touring Systems, Kylie Clarke, CODA Audio, Joel Edgerton, Dr Tony Kidman and the UTS Health Psychology Unit, Maurice Menswear Marrickville, Kirsty McGregor, Neil Phipps, Thomas Creative, David Trethewey and Martin McDonagh’s agent – The Rod Hall Agency Limited of 6th Floor Fairgate House 78 New Oxford St London WC1A 1HA. The Pillowman was first presented by the National Theatre at the Cottesloe, London, directed by John Crowley, on 13 November 2003. The production was subsequently produced on Broadway by the National Theatre, Robert Boyett Theatricals LLC and RMJF Inc. in association with Boyett Ostar, Robert Fox, Arielle Tepper, Stephanie P. McClelland, Debra Black, Dede Harris / Cover Image: Alex Craig Morton Swinsky / Roy Furman / Jon Avnet in association with Joyce Schweickert, Photography: Heidrun Löhr opening at the Booth Theatre, New York City, on 10 April 2005. DESIGN: Tim Kliendienst DIRECTOR’S NOTE Katurian: A great man once said is the relationship between art and ‘The first duty of a storyteller is to politics? And perhaps a key question tell a story’. -

027792 Clybourne Park Insert.Indd

Alex Logemann (Deck Manager) is celebrating OUR SPONSORS estate in 1993 and 1995. In 1997, an additional his 41st show backstage with Center REP. Alex has endowment from Dean Lesher’s estate followed been backstage for ten seasons and is beyond Chevron (Season Sponsor) has been the the death of Margaret Lesher. A significant pleased to be involved with such an amazing leading corporate sponsor of Center REP and and final bequest from Mr. Lesher’s estate CENTER REPERTORY COMPANY group. Alex has also worked backstage for Contra the Lesher Center for the Arts for the past nine was received in 2003. As a family foundation, Michael Butler, Artistic Director Scott Denison, Managing Director Costa Musical Theatre and with Diablo Theatre years. In fact, Chevron has been a partner of support for the Contra Costa community will the LCA since the beginning, providing funding be carried on by the next generation of family Company. Alex is a proud member of the Fantasy for capital improvements, event sponsorships members. Grant-making decisions are based presents Forum Actors Ensemble. He is very thankful for our and more. Chevron generously supports every on the vision of Dean and Margaret Lesher who community and the fun it provides. “Opportunity Center REP show throughout the season, and felt quality education, diverse art programs, and is missed by most people because it is dressed in is the primary sponsor for events including healthy children and families are the building overalls and looks like work.” -Thomas Edison the Chevron Family Theatre Festival in July. blocks of a strong and vibrant community. -

Quote from History Boys About the Nature of Education Being Erotic

VERGE 3 Cincotta 1 Molly Cincotta Dance and Theatre as Culture Metaphors February 2, 2006 The Attraction England Left Out “The transmission of knowledge is in itself an erotic act.” Hector History Boys (Bennett 53) Tom Stoppard is well known for his ability to tease out the ironies of life while staying just this side of clarity. His plays challenge audiences to keep up with a type of British intellectualism that celebrates the perceived ideals from the classical world. Yet in holding up a mirror to scholars past and present, Stoppard asks us to see beyond the ideal into paradox. The great poets, playwrights and philosophers of ancient Greece and Rome celebrated intellect hand in hand with love and passion, and yet British academia stresses the more Enlightenment-based triumph of knowledge over instinct. As writer Richard Ellmann puts it, “Artists could display their morality by fidelity to nature, and by eschewing self-indulgent sensuality” (qtd. Haill, The Beautiful 5). Love, passion, sex— this side of understanding the universe—was carefully removed from scholarship in favor of a detached acquisition of knowledge. Nor is it Stoppard alone among the playwrights who explore this contradiction. In his play History Boys, Alan Bennett looks at the same incongruity in the British school system of today. Even Oscar Wilde, a great influence on Stoppard, questioned the dual expectations of his society through his plays, most notably The Importance of Being Earnest. But while Wilde wrote in the midst of controversy and Bennett during modern day, it is Stoppard, specifically in his plays The Invention of Love VERGE 3 Cincotta 2 and Arcadia, who captures the enduring nature of this paradox throughout English history. -

Masculinity, Memory and the 1980S in British Cinema, 2005 – 2010

The History Boys? : Masculinity, Memory and the 1980s in British Cinema, 2005 – 2010 Andy Pope The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth School of Media and Performing Arts – University of Portsmouth May 2015 Abstract This study will consider the function of cinema in British society’s ongoing relationship with the 1980s. Its focus on a key period of recent British film history acknowledges popular culture’s flourishing identification with this decade, reflected through a number of media including literature, music and fashion. I argue that with seventeen films set in the 1980s and produced between 2005 and 2010, British cinema is at the centre of this retrospective, providing a unique perspective on our relationship with the era. But what are the determinants of this mediated reminiscence and what does it say about the function of cinema in rendering the past? I contend that a key aspect of this channelling of popular and personal memory is the role of the writer and director. Nearly all male and mostly middle- aged, the films’ creative agents present narratives that foreground young male protagonists and specifically masculine themes. These thematic concerns, including patriarchal absence and homosocial groups, whilst anchored in the concerns of their 1980s socio-political landscape also highlight a contemporary need for the films’ authors to connect to a personal past. Through reference to sociological, cinematic and political discourse, amongst others, this study will also consider the role of memory in these films. It will contend that the films present a complex perspective of the 1980s, highlighting an ambivalent relationship with the period that transcends nostalgia. -

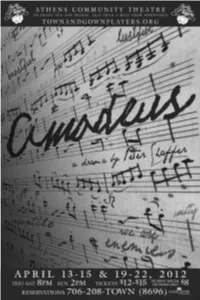

Amadeus Program.Pdf

ACT I The Streets of Vienna, 1823 Salieri’s Apartments, November 1823. The small hours. Transformation to the 18th Century, 1781-1791 The Palace of Schönbrunn, The Library of the Baroness Waldstädten Salieri’s Apartments The Palace of Schönbrunn The First Performance of The Abduction from the Seraglio Bonno’s Salon The Library of the Baroness Waldstädten Salieri’s Apartments ACT II Salieri’s Apartments The Palace of Schönbrunn Vienna and various Opera Houses Salieri’s Apartments An Unlit Theatre Same Theatre, the next day, the first perfomance of The Marriage of Figaro The Library of the Baroness Waldstädten Vienna and Palace of Schönbrunn The Prater A Masonic Lodge Mozart’s Apartment; Salieri’s Apartments En route to the Theatre by the Weiden The Theatre Salieri’s Apartments and outside in Vienna Mozart’s Apartment, 1791 Vienna Salieri’s Apartments, November 1823 CAST (in order of appearance) The “Venticelli” - John Otwell and Adam Shirley Salieri’s Valet - Andrew Lambert Salieri’s Cook - Rachel Steffens Antonio Salieri - Allen Rowell Joseph II - Tim Dowse Johann Kilian Von Strack - Skip Hulett Count Orsini-Rosenberg - Warren McPherson Baron Von Swieten - Briton Dean Giuseppe Bonno - Hue Henry Teresa Salieri - Jayne Lockhart Katherina Cavalieri - Danielle Bailey Miller Constanze Weber - Chelsea Toledo Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart - Patrick Najjar Major Domo - Richard Cassada Ludwig van Beethoven - Andrew Lambert Citizens of Vienna/Servants - Hannah Beth Reynolds, Lizzy Reese, Asia Meana, Patric Ryan, Daniel Cutts, Andrew Lambert, and Richard -

Waycross Twisted Tales of Poe Closer Than Ever

theatre.indiana.edu MALTBY AND SHIRE’S CLOSER THAN EVER Music by David Shire Lyrics by Richard Maltby Jr. Conceived by Steven Scott Smith Musical Direction by Terry LaBolt Directed and Choreographed by DJ Gray TWISTED TALES OF POE By Philip Grecian From the stories and poems of Edgar Allan Poe Directed by Richard Roland WAYCROSS By Jayne Deely Directed by Jenny McKnight IN PARTNERSHIP WITH WFIU AND THE IU LILLY LIBRARY A DIGITAL FESTIVAL JULY 18– 31 1 Message from the producer Welcome to IUST 2021! Indiana University Summer Theatre is thrilled to be back, providing professional theatre created here in Bloomington by our students, faculty, and guests. Given the cancellation of 2020's IUST due to the Covid-19 pandemic and the continued precautions surrounding in-person gatherings, IUST is proud to partner with WFIU to present two radio plays, and to also stream the fully staged musical Maltby and Shire's Closer Than Ever. Although we’d very much like to have a live audience, we are delving into this summer as an opportunity to expand our work and our student’s experience into audio plays and filmed musicals. We’ve had an incredible time, not only partnering with WFIU but also with the Lilly Library for our audio production of Twisted Tales of Poe. The silver lining is that this summer, many people both near and far can tune in to hear and view our IUST offerings for 2021! I’d also like to give a special thanks to our remarkable patrons and department friends who’ve supported us through this pandemic with financial gifts and letters of support. -

Playbill Was Created

Letter from the President Welcome to our 19th Season in which we explore and celebrate the theme of “Family”. As we attempt to recover from all of the carnage, offensive rhetoric, outlandish, atrocious and appalling shenanigans of this exceptionally divisive political season, we surely all feel the need to hold our loved ones just a little bit closer and to squeeze them a whole lot tighter. Thank you for coming out and sharing the next couple of hours with us as a part of our family. With your indulgence, we will transport you to a simpler time in the form of a good old fash- ioned comedy reminding us that differences can actually unite us; happiness is of higher value than money; and that family, with all of its quirks, challenges and surprises, also uplifts us with warmth, love, security and hope. We would love to have you become a larger part of our family either on stage or behind the scenes. If you are interested in playing with us or serving on our Board of Directors, please contact us by sending an e-mail to: [email protected]. Our annual fundraiser, A Night At The Cabaret, will be held on Saturday, February 4th 2017. This is a very fun evening with lots of entertainment showcasing some of our most talented performers. Please mark your calendar now as tickets tend to sell quickly! We will be posting details of the event, including a preview of items for the popular “Silent Auction”, over the next couple of weeks on our website at: www.longwoodplayers.org. -

Avocado Movement Theatre

UAB Town and Gown Productions ., � 1 . 1ll'te By Stephen Sondheim and Hugh Wheeler MAY7-17 AT CLARK THEATRE The Actor's Showcase Theatre Avocado Movement Theatre Choreography by Lori Cralg-Pulvlno MAY 19 - 23 AT BELL THEATRE Southern PlayWorks ..MANTRAP-" by Rob Nixon Directed by Sandra Taylor BELL THEATRE June 18 -June 28 -,:1NOINGIIOSe' by Bonnie Allee-Louise Morgan Directedby Jamie Lawrence BELL THEATREJuly9-July 19 .7HE DEVIL :SDREAM .. by Paul Ferguson Directedby Bess Peterson HOOVERLIBRARY THEATRE July 16-JulY25 "BUCK-NEKKID" by Jon Maxwell Directedby Janelle Cochran BIRMINGHAMFESTIVAL THEATREJuly 30-Aug. D ARCADIA BY ARCADIA TOM STOPPARD A play i11 tivo acts. The Story In 1993, an academic arrives at a country home to piece DIRECTOR together an alleged scandal involving the enigmatic poet BOBBY FUNK LordByron. As he constructs his version of events,we I I flash back to 1809 where, in the very same room,we COSTUME DESIGNER discoverwhat reallyhappened. Arcadia is a comic and INNAPOKRAS cosmic meditation on Romantic poetry, landscape gardening, Newtonian physics, adulteryand mortality, all SCENIC DESIGNER wrapped up in a time-travelingmystery. It proves that � KELL.AEGER anddesire throw everything into chaos. Stoppard is said to devour great stacks of background material in preparing to LIGHTING D.b--SIGNER write a play. LANG REYNOLDS Like much of his work, Arcadia is an elegant, intricate DRAMATURGE concoction of historical fact and theatrical invention. WILLIAM HUTCHINGS Arcadia juxtaposes two distinct sets of characters, in one gtaceful roomof the imaginaryEnglish estate of Sidley DIALECT COACH Park,in three separate moments in time: three daysin JILLBALCH COON 1809, one day in 1812, and several days in the present.