Anthony Turkevich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer Simulations and the Trading Zone

PETER &A Computer Simulations and the Trading Zone At the root of most accounts of the development of science is the covert premise that science is about ontology: What objects are there? How do they interact? And how do we discover them? It is a premise that underlies three distinct epochs of inquiry into the nature of science. Among the positivists, the later Carnap explicitly advocated a view that the objects of physics would be irretrievably bound up with what he called a "framework," a full set of linguistic relations such as is found in Newtonian or Eiustcini;~mechanics. That these frameworks held little in common did not trouble Car- nap; prediction mattered more than progress. Kuhn molded this notion and gave it a more historical focus. Unlike the positivists, Kuhn and other commentators of the 1960's wanted to track the process by which a community abandoned one framework and adopted another. To more recent scholars, the Kuhnian categoriza- tion of group affiliation and disaffiliation was by and large correct, but its underlying dynamics were deemed deficient because they paid insufficient attention to the sociological forces that bound groups to their paradigms. All three generations embody the root assumption that the analysis of science studies (or ought to study) a science classified and divided according to the objects of its inquiry. All three assume that as these objects change, particular branches of science split into myriad disconnected parts. It is a view of scientific disunity that I will refer to as "framework relativism. 55 In this essay, as before, I will oppose this view, but not by Computer Simulations I 19 invoking the old positivist pipe dreams: no universal protocol languages, no physicalism, no Corntian hierarchy of knowledge, and no radical reductionism. -

The Real Holocaust

THE REAL HOLOCAUST "Hitler will have no war, but he will be forced into it, not this year but later..." Emil Ludwig [Jew], Les Annales, June 1934 "We possess several hundred atomic warheads and rockets and can launch them at targets in all directions, perhaps even at Rome. Most European capitals are targets for our air force. Let me quote General Moshe Dayan: 'Israel must be like a mad dog, too dangerous to bother.' I consider it all hopeless at this point. We shall have to try to prevent things from coming to that, if at all possible. Our armed forces, however, are not the thirtieth strongest in the world, but rather the second or third. We have the capability to take the world down with us. And I can assure you that that will happen before Israel goes under." -- Martin van Creveld, Israeli professor of military history at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem in an interview in the Dutch weekly magazine: Elsevier, 2002, no. 17, p. 52-53. "We may never actually have to use this atomic weapon in military operations as the mere threat of its use will persuade any opponent to surrender to us." –Chaim Weizmann [Jew] "Jews Declared War on Germany. Even before the war started, the Jewish leaders on a worldwide basis had years before, declared that world Jewry was at war with Germany, and that they would utilize their immense financial, moral, and political powers to destroy Hitler and Nazi Germany. Principal among these was Chaim Weizmann, the Zionist leader, who so declared on September 5, 1939. -

Making a Manhattan Project National Historical Park

Atomic Heritage Foundation Preserving and Interpreting Manhattan Project History & Legacy Making A manhattan Project National Historical Park AnnualAnnual ReportReport 2010 Why should We Preserve the Manhattan Project? “The factories and bombs that Manhattan Project scientists, engineers, and workers built were physical objects that depended for their operation on physics, chemistry, metallurgy, and other natural sciences, but their social reality - their meaning, if you will - was human, social, political. We preserve what we value of the physical past because it specifically embodies our social past. When we lose parts of our physical past, we lose parts of our common social past as well.” “The new knowledge of nuclear energy has undoubtedly limited national sovereignty and scaled down the destructiveness of war. If that’s not a good enough reason to work for and contribute to the Manhattan Project’s historic preservation, what would be?” -Richard Rhodes, “Why We Should Preserve the Manhattan Project,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, May/June 2006 Remnant of the K-25 plant during the demolition of the east wing. See story on page 6. Front cover (clockwise from upper right): The B Reactor at Hanford, J. Robert Oppenheimer’s house in Los Alamos, and the K-25 Plant at Oak Ridge. These properties are potential components of a Manhattan Project National Historical Park. Table of Contents Board Members & Advisory Committee............3 George Cowan and Jay Wechsler Letter from the President......................................4 Manhattan Project Sites: Past & Present.......5 Saving K-25: A Work in Progress..........................6 AHF Releases New Guide............................................7 LAHS Hedy Dunn and Heather McClenahan. -

Monte Carlo Simulation Techniques

Monte Carlo Simulation Techniques Ji Qiang Accelerator Modeling Program Accelerator Technology & Applied Physics Division Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory CERN Accelerator School, Thessaloniki, Greece Nov. 13, 2018 Introduction: What is the Monte Carlo Method? • What is the Monte Carlo method? - Monte Carlo method is a (computational) method that relies on the use of random sampling and probability statistics to obtain numerical results for solving deterministic or probabilistic problems “…a method of solving various problems in computational mathematics by constructing for each problem a random process with parameters equal to the required quantities of that problem. The unknowns are determined approximately by carrying out observations on the random process and by computing its statistical characteristics which are approximately equal to the required parameters.” J. H. Halton, “A retrospective and prospective survey of the Monte Carlo Method,” SIAM Review, Vol. 12, No. 1 (1970). Introduction: What can the Monte Carlo Method Do? • Give an approximate solution to a problem that is too big, too hard, too irregular for deterministic mathematical approach • Two types of applications: a) The problems that are stochastic (probabilistic) by nature: - particle transport, - telephone and other communication systems, - population studies based on the statistics of survival and reproduction. b) The problems that are deterministic by nature: - the evaluation of integrals, - solving partial differential equations • It has been used in areas as diverse as physics, chemistry, material science, economics, flow of traffic and many others. Brief History of the Monte Carlo Method • 1772 Comte de Buffon - earliest documented use of random sampling to solve a mathematical problem (the probability of needle crossing parallel lines). -

Berni Alder (1925–2020)

Obituary Berni Alder (1925–2020) Theoretical physicist who pioneered the computer modelling of matter. erni Alder pioneered computer sim- undergo a transition from liquid to solid. Since LLNL ulation, in particular of the dynamics hard spheres do not have attractive interac- of atoms and molecules in condensed tions, freezing maximizes their entropy rather matter. To answer fundamental ques- than minimizing their energy; the regular tions, he encouraged the view that arrangement of spheres in a crystal allows more Bcomputer simulation was a new way of doing space for them to move than does a liquid. science, one that could connect theory with A second advance concerned how non- experiment. Alder’s vision transformed the equilibrium fluids approach equilibrium: field of statistical mechanics and many other Albert Einstein, for example, assumed that areas of applied science. fluctuations in their properties would quickly Alder, who died on 7 September aged 95, decay. In 1970, Alder and Wainwright dis- was born in Duisburg, Germany. In 1933, as covered that this intuitive assumption was the Nazis came to power, his family moved to incorrect. If a sphere is given an initial push, Zurich, Switzerland, and in 1941 to the United its average velocity is found to decay much States. After wartime service in the US Navy, more slowly. This caused a re-examination of Alder obtained undergraduate and master’s the microscopic basis for hydrodynamics. degrees in chemistry from the University of Alder extended the reach of simulation. California, Berkeley. While working for a PhD In molecular dynamics, the forces between at the California Institute of Technology in molecules arise from the electronic density; Pasadena, under the physical chemist John these forces can be described only by quan- Kirkwood, he began to use mechanical com- tum mechanics. -

Oral History Interview with Nicolas C. Metropolis

An Interview with NICOLAS C. METROPOLIS OH 135 Conducted by William Aspray on 29 May 1987 Los Alamos, NM Charles Babbage Institute The Center for the History of Information Processing University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Copyright, Charles Babbage Institute 1 Nicholas C. Metropolis Interview 29 May 1987 Abstract Metropolis, the first director of computing services at Los Alamos National Laboratory, discusses John von Neumann's work in computing. Most of the interview concerns activity at Los Alamos: how von Neumann came to consult at the laboratory; his scientific contacts there, including Metropolis, Robert Richtmyer, and Edward Teller; von Neumann's first hands-on experience with punched card equipment; his contributions to shock-fitting and the implosion problem; interactions between, and comparisons of von Neumann and Enrico Fermi; and the development of Monte Carlo techniques. Other topics include: the relationship between Turing and von Neumann; work on numerical methods for non-linear problems; and the ENIAC calculations done for Los Alamos. 2 NICHOLAS C. METROPOLIS INTERVIEW DATE: 29 May 1987 INTERVIEWER: William Aspray LOCATION: Los Alamos, NM ASPRAY: This is an interview on the 29th of May, 1987 in Los Alamos, New Mexico with Dr. Nicholas Metropolis. Why don't we begin by having you tell me something about when you first met von Neumann and what your relationship with him was over a period of time? METROPOLIS: Well, he first came to Los Alamos on the invitation of Dr. Oppenheimer. I don't remember quite when the date was that he came, but it was rather early on. It may have been the fall of 1943. -

Doing Mathematics on the ENIAC. Von Neumann's and Lehmer's

Doing Mathematics on the ENIAC. Von Neumann's and Lehmer's different visions.∗ Liesbeth De Mol Center for Logic and Philosophy of Science University of Ghent, Blandijnberg 2, 9000 Gent, Belgium [email protected] Abstract In this paper we will study the impact of the computer on math- ematics and its practice from a historical point of view. We will look at what kind of mathematical problems were implemented on early electronic computing machines and how these implementations were perceived. By doing so, we want to stress that the computer was in fact, from its very beginning, conceived as a mathematical instru- ment per se, thus situating the contemporary usage of the computer in mathematics in its proper historical background. We will focus on the work by two computer pioneers: Derrick H. Lehmer and John von Neumann. They were both involved with the ENIAC and had strong opinions about how these new machines might influence (theoretical and applied) mathematics. 1 Introduction The impact of the computer on society can hardly be underestimated: it affects almost every aspect of our lives. This influence is not restricted to ev- eryday activities like booking a hotel or corresponding with friends. Science has been changed dramatically by the computer { both in its form and in ∗The author is currently a postdoctoral research fellow of the Fund for Scientific Re- search { Flanders (FWO) and a fellow of the Kunsthochschule f¨urMedien, K¨oln. 1 its content. Also mathematics did not escape this influence of the computer. In fact, the first computer applications were mathematical in nature, i.e., the first electronic general-purpose computing machines were used to solve or study certain mathematical (applied as well as theoretical) problems. -

INTERSCALAR VEHICLES for an AFRICAN ANTHROPOCENE: on Waste, Temporality, and Violence

INTERSCALAR VEHICLES FOR AN AFRICAN ANTHROPOCENE: On Waste, Temporality, and Violence GABRIELLE HECHT Stanford University http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1445-0785 Brightly painted concrete houses, equipped with running water and elec- tricity, arranged in dozens of identical rows: this photograph (Figure 1) depicts the newly built company town of Mounana in eastern Gabon. The road is clean, the children happy. In the late 1970s, this image represented Gabonese “expec- tations of modernity” (Ferguson 1999) through national and corporate projects. By the end of this essay, I hope you will also see it as an image of the African Anthropocene. The idea of an African Anthropocene may seem like a paradox. After all, the biggest appeal of the idea of the Anthropocene has been its “planetarity” (DeLoughrey 2014). For some geologists, the Anthropocene signals the start of a new epoch, one in which humans permanently mark the stratigraphic record with their “technofossils” (Zalasiewicz et al. 2014). Other earth scientists adopt the notion to signal humanity’s catastrophic effects on the planet’s physical and biochemical systems. During the past decade, the term has become a “charismatic mega-category” (Reddy 2014) across the humanities, arts, and natural and social sciences (Steffen et al. 2011; Ellsworth and Kruse 2012). Inevitably, debates rage about origins and nomenclature. Did the Anthropocene begin with the dawn of human agriculture? Or with the Columbian exchange of the sixteenth and sev- enteenth centuries? How about the start of European industrialization in the eigh- CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY, Vol. 33, Issue 1, pp. 109–141, ISSN 0886-7356, online ISSN 1548-1360. -

Jerry Sabloff on 30 Years of Complexity

January / February 2014 UPDATE IN THIS ISSUE > Drinking & reciprocity 2 > Wolpert’s reality check 2 > SFI In the News 2 > SFI@30: From the editor 2 > Behavior & institutions 3 > Ruben Andrist: Quantum fragility 3 > Infectious notions 3 > SFI@30: Conception to birth 4 > Science symphony 5 > Eggs, bacon, & science 5 > 50 years of the quark 5 > New MOOC: Dynamics & chaos 6 > Award for Project GUTS 6 > Four new SFI trustees 7 > Books by SFI authors 7 > Marking SFI’s 30th year 8 > SFI@30: Co-founder David Pines 8 Q&A: Jerry Sabloff on 30 years of complexity At the turn of the new year, Institute are important new insights into the nature of standing of complex adaptive systems. So President Jerry Sabloff offers his thoughts complex adaptive systems and the transdisci- they instituted, almost into SFI’s DNA, a about SFI’s outlook for 2014 and beyond. plinary methodologies that SFI has used to transdisciplinary approach – anthropologists explore the emergence and continuing working with computer scientists and In 2014, SFI celebrates its 30th anniversary. Update: Today, with this interview, SFI development of complexity at all scales, from mathematicians and biologists and so on. Watch SFI’s website and publications begins to mark its 30th year. What are SFI’s atoms and cells to human societies. One of This methodology has proven to be incred- for a yearlong celebration of the Institute’s storied history, and for opportunities top achievements, in your mind, since its the great insights of SFI’s founders – the late ibly successful, and it is now widely adopted to be an active member of SFI’s community. -

The Emergence of Complexity

The Emergence of Complexity Jochen Fromm Bibliografische Information Der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar ISBN 3-89958-069-9 © 2004, kassel university press GmbH, Kassel www.upress.uni-kassel.de Umschlaggestaltung: Bettina Brand Grafikdesign, München Druck und Verarbeitung: Unidruckerei der Universität Kassel Printed in Germany Preface The main topic of this book is the emergence of complexity - how complexity suddenly appears and emerges in complex systems: from ancient cultures to modern states, from the earliest primitive eukaryotic organisms to conscious human beings, and from natural ecosystems to cultural organizations. Because life is the major source of complexity on Earth, and the develop- ment of life is described by the theory of evolution, every convincing theory about the origin of complexity must be compatible to Darwin’s theory of evolution. Evolution by natural selection is without a doubt one of the most fundamental and important scientific principles. It can only be extended. Not yet well explained are for example sudden revolutions, sometimes the process of evolution is interspersed with short revolutions. This book tries to examine the origin of these sudden (r)evolutions. Evolution is not constrained to biology. It is the basic principle behind the emergence of nearly all complex systems, including science itself. Whereas the elementary actors and fundamental agents are different in each system, the emerging properties and phenomena are often similar. Thus in an in- terdisciplinary text like this it is inevitable and indispensable to cover a wide range of subjects, from psychology to sociology, physics to geology, and molecular biology to paleontology. -

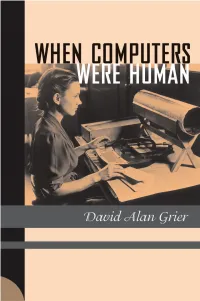

When Computers Were Human

When Computers Were Human When Computers Were Human David Alan Grier princeton university press princeton and oxford Copyright © 2005 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY All Rights Reserved Third printing, and first paperback printing, 2007 Paperback ISBN: 978-0-691-13382-9 The Library of Congress has cataloged the cloth edition of this book as follows Grier, David Alan, 1955 Feb. 14– When computers were human / David Alan Grier. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-691-09157-9 (acid-free paper) 1. Calculus—History. 2. Science—Mathematics—History. I. Title. QA303.2.G75 2005 510.922—dc22 2004022631 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Sabon Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ press.princeton.edu Printed in the United States of America 109876543 FOR JEAN Who took my people to be her people and my stories to be her own without realizing that she would have to accept a comet, the WPA, and the oft-told tale of a forgotten grandmother Contents Introduction A Grandmother’s Secret Life 1 Part I: Astronomy and the Division of Labor 9 1682–1880 Chapter One The First Anticipated Return: Halley’s Comet 1758 11 Chapter Two The Children of Adam Smith 26 Chapter Three The Celestial Factory: Halley’s Comet 1835 46 Chapter Four The American Prime Meridian 55 Chapter Five A Carpet for the Computing Room 72 Part II: -

Isotope and Nuclear Chemistry Division Annual Report FY1987

LA-1VSI-PR Progress Report UC~4 Issued: May 1988 LA-- 11 : Isotope and Nuclear Chemistry Division Annual Report FY1987 October 198$-Septemberl98? DonaldW. Barr,Division Leader JodyHHeiken, Editor OF H!! ayclHwmi is JNL Los Alamos National Laboratory |_os Alamos,New Mexico 87545 Acknowledgments Many skilled und knowledgeable individuals contributed to the production of this report the authors, te ihnical reviewers, illustrator, designer, photographers, word processors, and secretaries. The Division Office extends its thanks. Staff members who served as reviewers were Jere Knight (Overview), Alexander J, Gancarz (Sec. 1), P. Gary Eller (Sec. 2), David C. Moody (Sec. 3), Janet Mercer- Smith and Pat J. Unkefer (Sec. 4), Robert W. Charles (Sec. 5). Robert R. Ryan (Sec. 6). William H. Woodruff (Sec. 7), Jerry B. Wilhelmy (Sec. 8), Merle E. Bunker (Sec. 9), Charles M. Miller (Sec. 10), and Eugene J. Mroz 'Sec. 11). The publication team included Lia M. Mitchell, who interpreted the design, created many of the T^X macros and document files, and produced the final typeset, copy; Garth L. Tietjen (Group IS-12), the illustrator responsible for all final artwork; Gail E. Flower (Group IS-12), the designer; and Janey Headstream, who corrected documents and pasted up the report. The following individuals prepared original drafts: Kay L. Coen, Marielle S. Fenstermacher, Carla E. Gallegos, Janey Headstream, Lillian M. Hinsley, Lia M. Mitchell, C. Elaine Roybal, Cathy J. Schuch, and Sharon L. Sutherland. Photos for the cover ami inside front cover were taken by Henry F. Ortega of G roup IS-9, Portraits of INC personnel are the work of Leroy N.