Two Rich Minds - One Poor Invention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antique Radio Classified

ANTIQUE RADIO CLASSIFIED VOLUME 3 AUGUST 19E6 NUMBER 8 • QUAKER OATS CRYSTAL SET From the collection of Randall Renne - Dixon, IL THE NATIONAL PUBLICATION FOR BUYERS AND SELLERS OF OLD RADIOS AND RELATED ITEMS - PUBLISHED MONTHLY ANTIQUE RADIO CLASSIFIED Publishing Details Classified Ads Each subscriber is entitled to one 20 word classified ad Antique Radio Classified lUSPS 735-0901 is free of charge per issue. Additional words over the limit published monthly. 12 times yearly. at a suoscrip- are 10C per word. Multiple insertions of same ad are tion rate of $18.00 per year Second Class and discouraged. This is to allow for a varied ad content in each issue. Multiple insertion ads for more than $24.00 First Class mailing rates, by G.B.S. Enter- 2 issues must be run as a display ad. All ads must be prises, 9511 Sunrise Blvd.. 8.1-23. Cleveland, Ohio printed neatly and be received by the 8th of the month 44133. (216) 582-3094. before next issue. See classified ad details elsewhere Second-class postage paid at Cleveland, OH. in this issue. Publisher and Editor Gary B. Schneider. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to address Payment above. Copyright 1986... Antique Radio Classified All ads must be paid for in advance. Make checks payable to Antique Radio Classified. Purpose Antique Radio Classified is published for people in- Subscription Rate volved in the radio collecting hobby. Its purpose is to Subscriptions are available on a yearly basis. $18.00 stimulate growth of the hobby thru the buying, selling. per year Second Class and $24.00 First Class mailing and trading of radios and related items. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

_______________________ _____________________________________ En’, IWJI ‘III ‘" 11fl4-XIIH Il,. S-ki United States Department of the Interior NatiQnai Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. Name of Property Instorir name Massje Wireless Station other n;uneAsite number ‘ ‘ Pt]-’ 2. bntion street & nuinber 1300 Frenchtown Road not for publication: citxtown: East Greenwich viciuit N/A state: RI toil ntv Ken Msle: 0 0 3 ZIp isle: 02 8 1 8 3. Classificafion Ownership of Pms’rty: Private Tategorv of Piopertv: Building Nu mnber of flesoiLrtes with] ii Property: - Ton t riInit ii ig No ii 0 nt rihuli ng htHldilgs sites structures objects 1 p Total Number of toiitnhimting res4imrees previously listed in time National Ihgister Name ol related immumltiple property listiuig N/A ___________________________________________________________________ ______________ _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________ USDIiNPS Yil[fl Registration Form Page 2 Property name Nassie Wireless Station, Kent Cty. , East Greenwich, RI 4. StatelFederal Agency Certification As the tlt’signated authority under time National ii istonc Preservation Act of 1986, as amnendeil, I hereby certify that this_x_ nonminatiomi request for tleternii nat ion of eligibility meets the documnemitation standards for registermg pmoiwiies in the Nationi I Register of ii istoric Places and meets the procedural amid professional requ irenien ts set forth in 36 CFI1 Pa.rt. 60. In mmiv opi mm ion, tIme property J nieets does not meet the National Register Cr term. - See continuation sheet. 1. ‘ Gc Signature of certifying official Date State or Feil era I agency a mid himmriLil En umy op i iii u m, the i11 pe rtv meets ltfl’s mot uieet tIme Nat immII legister t-ri te ii a. -

Vintage Radio

VINTAGE RADIO Building a vintage radio "replica" Have you always wanted a 1920s or 1930s lacquer finish of some sort. Second, a glance at the front panel reveals that "cathedral" style radio. They're as scarce as these sets can receive FM transmis- sions as well as AM. In reality, FM hens' teeth these days - or are they? If you didn't get under way in Australia un- can't get an original, what about one of the til well after the era that the "replica" is supposed to represent. many replicas now coming onto the market? However, it's not until you expect the "insides" of such radios that you From time to time, "replicas" of ites but of course, they're not true realise just how far away they are early radio sets appear in catalog ad- replicas. First, the cabinets are noth- from being a true replica of the era. vertisements from various electronics ing like the those from the 20s, 30s Hidden inside the cabinet will be a and electrical retailers. Consoles and and 40s, usually being made from small transistor radio and that's hardly cathedral sets seem to be the favour- cheap ply or particle board with a something that was around in the 1920s or 1930s! So these sets are in no way an accu- rate copy or replica of any early radio. The fact is, there are very few genu- ine 1920s (and not many more 1930s) sets now available on the market. Many collectors will never own ra- dios of this vintage. -

Short Wave Radio

Short Wave Radio A Working Electronic Sculpture Honoring the History of Radio Please note: This radio picks up short wave stations, but for your best satisfaction it will require a little time and attention, both to learn how to operate it and to appreciate the principles and history that it embodies. You’ll find bare-bones instructions on this page and more details inside the notebook. To turn the radio on, rotate the volume control clockwise until you hear a click, then set its dial to 3 or 4. If the radio was not already turned on, you’ll have to wait about 30 seconds for its vacuum tubes to warm up. •Put on the headphones. •Set the radio’s other controls as follows: •RF Gain: Fully clockwise. •Preselector: 1 •Tuning: 20 •Fine Tuning: 5.0 (This works like a clock, only with ten “hours” instead of 12) •Regeneration: 7 (Or advance slowly clockwise from zero until just after the point you hear a louder hiss in the headphones.) •Volume: Set to a comfortable level, usually about 4. Now, slowly adjust the TUNING control back and forth looking for squeals that indicate signals. (The shortwave broadcast band with 31 meter wavelength is located between about 10 and 30 on the dial.) You’ll should find a few unless ionospheric conditions are particularly poor on this day. Leave the TUNING control set on a loud squeal. Then slowly adjust the FINE TUNING to “zero beat.” (You’ll notice as you move the dial across a signal, it starts with a high-pitched note, moving down to a low-pitched or zero note, then back up to high pitch again. -

1994-11: Browning-Drake

Vii luta gic IRaidl iio by PETER LANKSHEAR The Browning-Drake receiver One of the best remembered radio names from the 1920's is 'Browning-Drake', a receiver which combined simplicity with what for its time was a rate performance. While most of its contempo- raries had production lives of little more than a year, the Browning-Drake design was popular for much of the decade. As with the IBM personal computer'. it. recently, there were also more 'clones' made by others than the official versions... By the outbreak of World War I, valve cluding them in tuned circuits coupling The alternative method, and of course receiver technology had advanced to the the valves. However the tuned RF ampli- the ultimate solution to many difficulties stage where stable detection and low fre- fier then ran into another problem. Tri- was the superheterodyne, attributed by quency amplification were possible. ode valves have sufficient inter-ekctrode Americans to work done in 1918 by Ma- However there were limitations to the capacitance that with tuned circuits con- jor Edwin Armstrong of the US Army. sensitivity and selectivity of the grid leak nected to both anode and grid, there is While much credit is due to Armstrong, it detectors that had become standard. sufficient energy transferred internally is now clear that the original concept of The newly discovered regeneration back to the grid to cause them to become the superhet was an international effort, helped, but it became clear that the only vigorous oscillators. with much of the early work being done way to improve receiver sensitivity was Initially there were two solutions. -

Man of High Fidelity

Man of High Fidelity: EDWIN HOWARD ARMSTRONG A Biography – By Lawrence Lessing With a new forward by the author Page iii Pratt DISCLAIMER DISCLAIMER TO THIS SCANNED AND OCR PROCESSED COPY This PDF COPY is for use at Pratt Institute for Educational Purposes Only I affirm that sufficient print copies of the original Bantam Book Paperback are in stock in ARC E-08 that would more than adequately cover a full class use of the text. HOWEVER, due to the fact that the 1969 text is no longer in publication, complicated by the fact that these copies are forty-four (44) years old and in a very fragile condition, this PDF version of the text was created for student use in the Department of Mathematics and Science. - Professor Charles Rubenstein, January 2013 Man of High Fidelity: Edwin Howard Armstrong EDWIN HOWARD ARMSTRONG Was the last – and perhaps the least known – of the great American Inventors. Without his major contributions, the broadcasting industry would not be what it is today, and there would be no FM radio. But in time of mushrooming industry and mammoth corporations, the recognition of individual genius is often refused, and always minimized. This is the extraordinary true story of the discovery of high fidelity, the brilliant man and his devoted wife who battled against tremendous odds to have it adopted, and their long fight against the corporations that challenged their right to the credit and rewards. Mrs. Armstrong finally ensured that right nearly ten years after her husband’s death. Page i Cataloging Information Page This low-priced Bantam Book has been completely reset in a type face designed for easy reading, and was printed from new plates. -

Antique Radio Charlotte an Annual Conference for Antique and Vintage Radio Collectors and Historians

Antique Radio Charlotte An annual conference for antique and vintage radio collectors and historians. 3rd Bi-annual Charlotte International Cryptologic Symposium Thursday, Friday & Saturday March 24-25-26, 2016 Sponsored by the Carolinas Chapter of the Antique Wireless Association Meet Results CAROLINAS CHAPTER OF THE AWA http://www.cc-awa.org/ PRESIDENT SECRETARY-TREASURER Ron Lawrence Clare Owens P O Box 3015 101 Grassy Ridge Ct. Matthews, NC 28106 Apex NC 27502 704-289-1166 919-363-7608 [email protected] [email protected] VICE PRESIDENT Richard Owens EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE R L Barnett Stephen Brown Kirk Cline Barker Edwards Robert Lozier Chip McFalls EDITORS Barker & Judy Edwards 116 East Front Street Clayton NC 27520 919 553-2330 [email protected] Membership in the Carolinas Chapter of the Antique Wireless Association (CC-AWA) is open to anyone with an interest in old (antique) radios. Anyone who pays registration for the 2016 conference will automatically receive one year’s membership in the Carolinas Chapter of the AWA. This is only chapter membership and does not include membership in the Antique Wireless Association. If you are already a paid member in the chapter, your membership will be extended one year. Any correspondence, including any newsletters that are published, will be distributed electronically. Please make sure that the CC-AWA has a current email address on file. Old Equipment Contest Pictured are the 1st place winners. To view all the winners, please visit our web page at: www.cc-awa.org. HM-Honorable mention No Entries CATEGORY 1 PRE-1912 ELECTRICAL DEVICES NON RADIO No Entries CATEGORY 2 PRE-1920 RECEIVERS & TRANSMITTERS AND WIRE LINE TELEGRAPH ITEMS CATEGORY 3 1920s ERA BROADCAST RECEIVERS A. -

Construction and Operation of a Simple Homemade Radio Receiving Outfit

Construction and Operation of a Simple Homemade Radio Receiving Outfit The 1922 Bureau of Standards publication, Construc- tion and Operation of a Simple Homemade Radio Receiving Outfit [1], is perhaps the best-known of a series of publications on radio intended for the general public at a time when the embryonic radio industry in the U.S. was undergoing exponential growth. While there were a number of earlier experiments with radio broadcasts to the general public, most histori- ans consider the late fall of 1920 to be the beginning of radio broadcasting for entertainment purposes. Pittsburgh, PA, station KDKA, owned by Westinghouse, received its license from the Department of Commerce just in time to broadcast the Harding-Cox presidential election returns. In today’s world where instant global communications are commonplace, it is difficult to appreciate the excitement that this event generated. Fig 1. The crystal radio described in Circular 120. News of the new development spread rapidly, and interest in radio soared. By the end of 1921, new broad- casting stations were springing up all over the country. Radios were selling faster than companies could manu- facture them. The demand for information on this new technology was almost insatiable. The Radio Section of the Bureau of Standards provided measurement know- how to the burgeoning radio industry as well as general information on the new technology to the public. Letters to the Bureau seeking information on radio technology began as a trickle, and then soon became a flood. Answering them became a burden. Circular 120, published in April 1922, began: “Frequent inquiries are received at the Bureau of Standards for information regarding the construction of a simple receiving set which any person can construct in the home from materials which can be easily secured. -

A Practical Neutrodne Receiver by ALLAN T

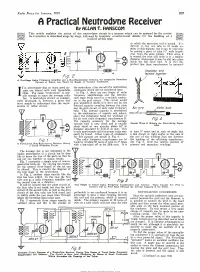

Radio News for January, 1924 899 A Practical Neutrodne Receiver By ALLAN T. HANSCOM This article explains the action of the neutrodyne circuit in a manner which can be grasped by the novice. Its formation is described stage by stage, followed by complete constructional details for the building of a receiver of this type. on which the secondary coil is wound. It is difficult to buy one tube to fit inside an- other in this manner, but it can be overcome by sawing a piece of tube /" wide length- wise from the same tubing. Then when it is wound, the wire will draw it to a smaller diameter whereupon it may be slid into place inside the full sized tube. It is very im- portant that these transformers be mounted Insulated wire fig. 2 /w/sted together A One -Stage Radio Frequency Amplifier and a Non- Regenerative Detector, the Respective Secondary Circuits of Which Are Tuned by Means of Variable Condensers. IT is unfortunate that so many good cir- the neutrodyne after we add the neutralizing cuits are labeled with such formidable condensers which will be considered later. titles. The name "neutrodyne" is usu- In Fig. 3, there are two stages of radio ally enough to scare the average radio frequency amplification and the detector, fan. A neutrodyne circuit, as commer- each stage being tuned by a variable conden- cially developed, is, however, a great deal ser in the grid circuit. This circuit would more simple to understand than the regen- give wonderful results if it were not for the erative or reflex circuit. -

Journal Vol 9-X 1985

Ctil?~ ()fflclal JI ~()IU IV~ A\ IL JAN - MAR 1985 CALIFORNIA HISTORICAL RADIO SOCIETY PRESIDENT: NORMAN BERGE SECRETARY: BOB CROCKETT TREASURER: JOHN ECKLAND EDITOR: HERB BRAMS PHOTOGRAPHY: GEORGE DURFEY CONTENTS CLUB NEWS •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• • . l THE SUPERHETERODYNE RECEIVER ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 3 WHAT KIND OF COLLECTOR ARE YOU? •••••••••••••••••••••••••• 20 BALLAST TUBES AND RESISTANCE LINE CORDS ••••••••••••••••••• 21 ADVERTISEMENTS •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 24 THE SOCIETY ll\e California Historical Radio Society is a non-profit corporation chartered in 1974 to promote the preservation of early radio equipment and radio broadcasting. CHRS provides a meditDD for members to exchange infor mation on the history of radio with emphasis on areas such as collecting, cataloging and restoration of equipment, literature. and programs. Regular swap meets are scheduled four times a year. For further information, write the California Historical Radio Society, P. O. Box 1147, Mountain View , CA 94042-114 7. THE JOURNAL ll\e official Journal of the California Historical Radio Soc i ety i a published six times a year and is furnished free to all members. Articl e• for the Journal are solicited from all members. Appropriate subjects include information on early radio equipment. personalities, or broadcasts, restoration hints, photographs, ads, etc. Material for the Journal should be sulrnitted to the Editor, Herb Brams, 2427 Durant #4, Berkeley, CA 94704. MEMBERSHIP Membership correspondence should be addressed to the Treasurer, John Eckland, 969 Addison Ave., Palo Alto, CA 94301. CHRS SWAP MEETS CHRS swap meets have tentatively been set for the following dates: June 1, Aug. 31, and Nov. 9 at Foothill College. Notices will be sent if these dates are changed. -

Alignment and Neutralization of the Early Ac Trf & Neutrodyne Receivers

ALIGNMENT AND NEUTRALIZATION OF THE EARLY AC TRF & NEUTRODYNE RECEIVERS by Lane S. Upton 3788 S. Loretta Dr. Salt Lake City, UT 84106-2956 For a radio to work as it was originally designed, it must be in proper alignment. This means that at any single point on the dial all tuned circuits must be at resonance and the dial calibration should be correct. In the case of neutrodyne receivers, additional steps must be taken to assure that each neutralized amplifier stage is adjusted properly. This will assure that the full gain can be realized. The purpose of this article is to provide a detailed review of the steps necessary to completely align these receivers. Much was written on this subject when the radios were relatively new, but it was all directed toward working on a "modern" receiver only a few years old. Today, we must look at warped variable condensers, worn wiper contacts, poor ground connections, coil windings that have shifted position, incorrectly positioned coils, loose shield cans, and many other problems brought about by age and abuse. The time spent doing a complete alignment will typically result in a radio with greatly improved selectivity and sensitivity. This is especially true at the lower frequency portion of the dial. Preliminary Work The initial work on a set must include inspection of all the components that will affect alignment. This should not be limited to the variable condenser and coils, but must include all other items that can have any effect. The following steps represent a basic outline of the preliminary work that should be carried out. -

Extended Call for Papers

A Century of Broadcasting histelcon 2010 The Second Region 8 IEEE Conference on the History of Telecommunications Madrid, Spain 3-5 November 2010 http://www.aeit.es/histelcon2010/ EXTENDED CALL FOR PAPERS Theme and Topics Year 2010 marks a series of historical milestones in relation to the Birth of Broadcasting a hundred years ago. To commemorate this remarkable anniversary, we invite submissions related to this theme in order to be presented as a paper. Other papers describing significant research contributions to the field of History of Information and Communication Technologies are also welcome. The official language of the conference will be English. Topics of interests include, but are not limited to, the following: • Pioneers of Broadcasting, • The Birth of the Broadcasting Business, • Stellar Moments in the History of Broadcasting, • A Century of Radio Regulations, • Radio & TV Standards, • Broadcasting as a Political Instrument, • Development of Radio & TV Technology. Poster and Special Sessions Submissions to organize a poster session on antique radio and radio museums or other related subject are very welcome. In addition, we are also seeking proposals for special sessions. Some suggestions come next: IEEE Life-Members and History Activities, Ham (Amateur) Radio, Pirate Radio, Satellite & Cable Broadcasting, Internet TV & Radio, Broadcasting as Entertainment. With the Sponsored by: collaboration of: A Century of Broadcasting histelcon 2010 The Second Region 8 IEEE Conference on the History of Telecommunications Madrid, Spain 3-5 November 2010 http://www.aeit.es/histelcon2010/ Abstract Submission Interested participants are invited to submit their abstracts for oral or poster presentations to the Conference Secretariat by electronically sending a 500 words abstract, written in English, with a title, the name of the author(s) and affiliation(s) in MS Word format.