International Journal of English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homosexuality and Gender Expression in India

Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │2016 Homosexuality and Gender Expression in India Chelsea Peer Abilene Christian University Texas Psi Chapter Vol. 1(1), 2016 Article Title: Homosexuality and Gender Expression in India DOI: 10.21081/ax0021 ISSN: 2381-800X Key Words: homosexuality, India, Raj, Hindu, transgender, LGBT This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Author contact information is available from the Editor at [email protected]. Aletheia—The Alpha Chi Journal of Undergraduate Scholarship • This publication is an online, peer-reviewed, interdisciplinary undergraduate journal, whose mission is to promote high quality research and scholarship among undergraduates by showcasing exemplary work. • Submissions can be in any basic or applied field of study, including the physical and life sciences, the social sciences, the humanities, education, engineering, and the arts. • Publication in Aletheia will recognize students who excel academically and foster mentor/mentee relationships between faculty and students. • In keeping with the strong tradition of student involvement in all levels of Alpha Chi, the journal will also provide a forum for students to become actively involved in the writing, peer review, and publication process. • More information and instructions for authors is available under the publications tab at www.AlphaChiHonor.org. Questions to the editor may be directed to [email protected]. Alpha Chi is a national college honor society that admits students from all academic disciplines, with membership limited to the top 10 percent of an institution’s juniors, seniors, and graduate students. Invitation to membership comes only through an institutional chapter. A college seeking a chapter must grant baccalaureate degrees and be regionally accredited. -

The Legal, Colonial, and Religious Contexts of Gay and Lesbian Mental Health in India Tanushree Mohan Submitted in Partial Fulfi

The Legal, Colonial, and Religious Contexts of Gay and Lesbian Mental Health in India Tanushree Mohan Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in Women’s and Gender Studies under the advisement of Nancy Marshall April 2018 © 2018 Tanushree Mohan ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my thesis advisor, Nancy Marshall, for offering her constant support throughout not just this thesis, but also the duration of my entire Women and Gender Studies Major at Wellesley College. Thank you for all of your insightful comments, last minute edits, and for believing in my capabilities to do this thesis. Next, I would like to thank the seven people who agreed to be interviewed for the purposes of this thesis. Although I can only refer to you as Interviewees A, B, C, D, E, F and G, I would like to state that I am very grateful to you for your willingness to trust me and speak to me about this controversial topic. I would also like to thank Jennifer Musto, whose seminar, “Transnational Feminisms”, was integral in helping me formulate arguments for this thesis. Thank you for speaking to me at length about this topic during your office hours, and for recommending lots of academic texts related to “Colonialism and Sexuality” that formed the foundation of my thesis research. I am deeply grateful to The Humsafar Trust, and Swasti Health Catalyst for providing their help in my thesis research. I am also thankful to Ashoka University, where I interned in the summer of 2016, and where I was first introduced to the topic of LGBTQIA mental health, a topic that I would end up doing my senior thesis on. -

Crocodile Tears”

CHAPTER THREE QUEER KINSHIP IN NEW QUEER INDIA: FROM WADIA’S BOMGAY TO R. RAJA RAO’S “CROCODILE TEARS” ROHIT K DASGUPTA Established academic debates surrounding representation of queer identities in India have time and again illuminated the relationship between sexual (and gendered) subjectivities and the state. More often than not queer individuals themselves have fixated on heteronormativising their queerness. For many, such articulations of “fitting in” with the rest evidence a social/cultural and even political progress, but for radical queer activists and scholars this signifies a backward trend of servicing the neo- liberal agenda. Lisa Duggan (2002, 179) has called this homonormativity and has argued that it is “a politics that does not contest dominant heteronormative assumptions and institutions but upholds and sustains them while promising the possibility of a demobilized gay constituency and a privatized, depoliticized gay culture anchored in domesticity and consumption”. This essay therefore is a mediation of and an argument against this neo-liberal progress which assumes a universal queer identity (see Massad 2007 and Altman 1997) structured around normative family structures (through same sex marriages and adoption) and a de-essentialising of the queer body through hyper masculinity/femininity (Dasgupta and Gokulsing 2014). As recent research has suggested,there are newer ways to understand queerness beyond the state sponsored homonormativities (Puar 2006). Scholar and activist Judith Halberstam’s recent work on Gaga feminism (2012) sifts through popular cultural artefacts to uncover how these media artefacts contain within them a blueprint of dominant (heteronormative/mainstream) culture with its emphasis on stasis, norms and conventions. -

The Hindu, the Muslim, and the Border In

THE HINDU, THE MUSLIM, AND THE BORDER IN NATIONALIST SOUTH ASIAN CINEMA Vinay Lal University of California, Los Angeles Abstract There is but no question that we can speak about the emergence of the (usually Pakistani or Muslim) ‘terrorist’ figure in many Bollywood films, and likewise there is the indisputable fact of the rise of Hindu nationalism in the political and public sphere. Indian cinema, however, may also be viewed in the backdrop of political developments in Pakistan, where the project of Islamicization can be dated to least the late 1970s and where the turn to a Wahhabi-inspired version of Islam is unmistakable. I argue that the recent history of Pa- kistan must be seen as instigated by a disavowal of the country’s Indic self, and similarly I suggest that scholarly and popular studies of the ‘representation’ of the Muslim in “Bol- lywood” rather too easily assume that such a figure is always the product of caricature and stereotyping. But the border between Pakistan and India, between the self and the other, and the Hindu and the Muslim is rather more porous than we have imagined, and I close with hints at what it means to both retain and subvert the border. Keywords: Border, Communalism, Indian cinema, Nationalism, Pakistan, Partition, Veer-Zaara Resumen 103 Así como el personaje del ‘terrorista’ (generalmente musulmán o paquistaní) está presente en muchos filmes de Bollywood, el nacionalismo hindú está tomando la iniciativa en la esfera política del país. Sin embargo el cine indio también puede hacerse eco de acontecimientos ocurridos en Paquistán, donde desde los años Setenta se ha manifestado un proceso de islamización de la sociedad, con una indudable impronta wahabí. -

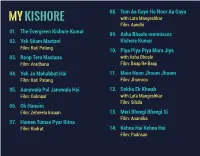

Kishore Booklet Copy

08. Tum Aa Gaye Ho Noor Aa Gaya with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Aandhi 01. The Evergreen Kishore Kumar 09. Asha Bhosle reminisces 02. Yeh Sham Mastani Kishore Kumar Film: Kati Patang 10. Piya Piya Piya Mora Jiya 03. Roop Tera Mastana with Asha Bhosle Film: Aradhana Film: Baap Re Baap 04. Yeh Jo Mohabbat Hai 11. Main Hoon Jhoom Jhoom Film: Kati Patang Film: Jhumroo 05. Aanewala Pal Janewala Hai 12. Dekha Ek Khwab Film: Golmaal with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Silsila 06. Oh Hansini Film: Zehreela Insaan 13. Meri Bheegi Bheegi Si Film: Anamika 07. Hamen Tumse Pyar Kitna Film: Kudrat 14. Kehna Hai Kehna Hai Film: Padosan 2 3 15. Raat Kali Ek Khwab Mein 23. Mere Sapnon Ki Rani Film: Buddha Mil Gaya Film: Aradhana 16. Aate Jate Khoobsurat Awara 24. Dil Hai Mera Dil Film: Anurodh Film: Paraya Dhan 17. Khwab Ho Tum Ya Koi 25. Mere Dil Mein Aaj Kya Hai Film: Teen Devian Film: Daag 18. Aasman Ke Neeche 26. Ghum Hai Kisi Ke Pyar Mein with Lata Mangeshkar with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Jewel Thief Film: Raampur Ka Lakshman 19. Mere Mehboob Qayamat Hogi 27. Aap Ki Ankhon Mein Kuch Film: Mr. X In Bombay with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Ghar 20. Teri Duniya Se Hoke Film: Pavitra Papi 28. Sama Hai Suhana Suhana Film: Ghar Ghar Ki Kahani 21. Kuchh To Log Kahenge Film: Amar Prem 29. O Mere Dil Ke Chain Film: Mere Jeevan Saathi 22. Rajesh Khanna talks about Kishore Kumar 4 5 30. Musafir Hoon Yaron 38. Gaata Rahe Mera Dil Film: Parichay with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Guide 31. -

Rudhramadevi 2 Movie in Hindi 720P

Rudhramadevi 2 Movie In Hindi 720p 1 / 6 Rudhramadevi 2 Movie In Hindi 720p 2 / 6 3 / 6 Watch Rudhramadevi 3D Hindi Full HD Movie with 5.1 Audio.Rudhramadevi movie Written, Produced and Directed by Gunasekhar. ... 0:00 / 2:36:02. Live ... Antim Faisla (Vedam) Hindi Dubbed Full Movie | Allu Arjun, Anushka .... Rudhramadevi (2015). Dual Audio - Hindi+Tamil - 720p HDRip 900MB - (RD7).. Keyword 1720p tamil dubbed hollywood movies download. Keyword 2 . 720p ... 1. rudhramadevi movie hindi 2. rudhramadevi movie hindi download 720p 3. rudhramadevi movie hindi mein Amazon.in - Buy Rudhramadevi at a low price; free delivery on qualified orders. ... All items in Movies & TV shows are non returnable. ... Run time : 2 hours and 37 minutes; Release date : 16 December 2015; Actors : Anushka Shetty, Allu Arjun, Rana Daggubati, Anushka Shetty, Allu Arjun; Dubbed: : Hindi; Studio : Big Music .... Rudhramadevi 2018 Hindi Dubbed 720p HDRip 1.1GB ... Allu Arjun, Rana Daggubati Movie Plot: Queen Rudrama Devi's reign in southern India during the 13th .... Top Rated Telugu Movies. Find out which Telugu movies got the highest ratings from IMDb users, from classics to recent blockbusters.. Gunasekhar in 3D. The film is simultaneously being made in Telugu and Tamil.It is being dubbed in Kannada, Hindi and Malayalam, this movie will be the first .... Mar 1, 2020 - Watch Rudhramadevi 2D Hindi Full HD Movie. Rudhramadevi movie Written, Produced and Directed by Gunasekhar. ... Time Machine - New Latest Hindi Dubbed Movie | 2019 South Action Latest ... Movies 2019Hd ... Trần Trung Kỳ Án Phần 2 Tập 28 THVL1 Full HD ( VIP Nhanh ) Ngày 25/09/2018. -

Honouring a Legend Zafri Mudasser Nofil “Kinara”, “Khushboo”, “Angoor”, “Libaas” , “Meera”, Everyone Knows Shilpa Shetty Kundra's Entrepreneurial Skills

SUNDAY, APRIL 27, 2014 (PAGE-4) BOLLYWOOD BUZZ PERSONALITY "Business is a part of life" Honouring a legend Zafri Mudasser Nofil “Kinara”, “Khushboo”, “Angoor”, “Libaas” , “Meera”, Everyone knows Shilpa Shetty Kundra's entrepreneurial skills. “Lekin” and “Maachis”. The prestigious Dada Saheb Phalke He has worked on the small screen as well; Along with her businessman husband Raj Kundra, she has award could not have been conferred having created outstanding series like “Mirza on a more deserving person than Ghalib” and “Tahreer Munshi Premchand now launched her gold bullion and jewellery veteran lyricist-ffilmmaker and Ki”. He wrote lyrics for several Doordar- poet Gulzar. He was chosen for shan serials including “Hello Zindagi”, the highest official recognition “Potli Baba Ki” and “Jungle Book”. company - Satyug Gold. Sreya Basu in conversation for film personalities in India Gulzar was awarded the Sahitya for outstanding contribution Akademi Award in 2002, the Padma with the actress in Mumbai on her latest project. to the growth and develop- Bhushan in 2004. He has won a ment of Indian cinema. number of National Film Awards After trying your hand in wellness of today. A seven-member jury and 20 Filmfare Awards. He won and fitness business (Iosis Medi You launched Satyug Gold in three cities consisting of eminent the Oscar for best original song Spa), cricket (Rajasthan Royals co- (Bandra in Mumbai, Pune and Ahmedabad) artistes unanimously rec- ‘Jai ho’ with Rahman for “Slum- owner), film production simultaneously on the same day. What ommended the 79-year- dog Millionaire” in 2009. In 2010, (Dishkiyaaoon) and real estate made you come up with the idea? old Gulzar for the presti- Gulzar also won the Grammy (grouphomebuyer.com), you are I was running out of time. -

21 Aug Page 07.Qxd

SWAPNIL SANSAR, ENGLISH WEEKLY,LUCKNOW, 28,MARCH, (07) Tragedy Queen of Indian Cinema Contd.From Page no.06 the film's music and lyrics were by Roshan and Sahir to August, Meena Kumari was in the hands of Dr. Sheila Sherlock.Upon Ludhianvi and noted for songs such as "Sansaar Se Bhaage Phirte Ho" and recovery, Meena Kumari returned to India in September 1968 and on the fifth "Mann Re Tu Kaahe". Ghazal directed by Ved-Madan, starring Meena Kumari day after her arrival, Meena Kumari, contrary to doctors' instructionsAAfter their and Sunil Dutt, was a Muslim social film about the right of the young generation marriage, Kamal Amrohi allowed Meena Kumari to continue her actiresumed to the marriage of their choice. It had music by Madan Mohan with lyrics by work. Suffering from cirrhosis of the liver, although Meena Kumari temporarily Sahir Ludhianvi, featuring notable filmi-ghazals such as "Rang Aur Noor Ki recovered but was now much weak and thin. She eventually shifted her focus Baraat", performed by Mohammed Rafi and "Naghma O Sher Ki Saugaat" on more 'acting oriented' or character roles. Out of her last six releases namely performed by Lata Mangeshkar. Main Bhi Ladki Hoon was directed by A. C. Jawab, Saat Phere, Mere Apne, Dushman, Pakeezah & Gomti Ke Kinare, she Tirulokchandar. The film stars Meena Kumari with newcomer Dharmendra. only had a lead role in Pakeezah. In Mere Apne and Gomti Ke Kinare, although Critical acclaim (1962) Sahib Bibi Aur she didn't play a typical heroine role, but her character was actually the central Ghulam (1962) character of the story. -

Azamgarh Dealers Of

Dealers of Azamgarh Sl.No TIN NO. UPTTNO FIRM - NAME FIRM-ADDRESS 1 09185100008 AZ0019063 BOMBAY SUPARY STORE CHAUKTAHSIL SADAR, AZAMGARH. 2 09185100013 AZ0039267 BAJRANG IRON STORE THEKMA TAHSIL LALGANG AZAMGARH 3 09185100027 AZ0055527 BARBWAL HOMAO HALL ASIFGANJ,SADAR, AZAMGARH. 4 09185100032 AZ0058356 GULAB CHAND BRIJ PAL DAS ASIFGANJ, AZAMGARH. 5 09185100046 AZ0067666 MEDICO PHARMA AGENCY KURMI TOLA SADAR, AZAMGARH. 6 09185100051 AZ0069266 HAINIMEN PYOUR DRUGS COMPANY CIVIL LINES, AZAMGARH. 7 09185100065 AZ0080507 RAM LAKHAN JAISWAL TARWA, AZAMGARH. 8 09185100070 AZ0074855 DHARM DAV CONT. SUFDDINPUR AZAMGRH 9 09185100079 AZ0080734 RAM MEDICAL AGENCY PHARPUR AZAMGARH 10 09185100084 AZ0081089 VINDO GLASS IMPORIAL CHAUK TAHSIL SADER AZAMGARH 11 09185100098 AZ0086052 RAM JATAN YADAV B.K.O. DAGARPUR, AZAMGARH. 12 09185100107 AZ0090190 VIDAYRTHI PUSTAK MANDIR PAHARPUR, AZAMGARH. 13 09185100112 AZ0090328 RAVENDRA TRADERS DIHA AZAMGARH 14 09185100126 AZ0093095 RAJENDRA KASHTHA INDUSTRIES KAPTANGANJ, AZAMGARH. 15 09185100131 AZ0094057 MURALI COLD STORES & ICE FACTARI BELAISA, AZAMGARH. 16 09185100145 AZ0095670 DHANAI RAM PYARE LAL LAL GANJ AZAMGRH 17 09185100150 AZ0096280 ROYAL MEDICAL STORE KHATRI TOLA, AZAMGARH. 18 09185100159 AZ0097079 RAM ADHAR CONTRACTOR KAPTANGANJ, AZAMGRH. 19 09185100164 AZ0097738 RAMA INT BHATTA SARRA AZAMGARH 20 09185100178 AZ0099868 ROSHANI MAHAL KHATRI TOLA, AZAMGARH. 21 09185100183 AZ0101920 BALIRAM ENTERPRISES LALGANJ T.LALGANJ,AZAMGARH. 22 09185100197 AZ0102036 RANJEET SINGH THEKEDAR AKSHAIBAR, AZAMGRH. 23 09185100206 AZ0103127 BENI MEDICAL HALL UTROULA BUDHANPUR AZAMGARH. 24 09185100211 AZ0103957 ROHITAS TRADERS CO. HARI KI CHUNGI AZAMGARH 25 09185100225 AZ0105181 RAM DARASH B.K.O. HATHIPUR, AZAMGARH. 26 09185100230 AZ0105815 RAM PHER YADAV ENT BHATTA HAKARIPAR, AZAMGARH. 27 09185100239 AZ0106312 CHASMA SAGAR MATVARGANJ, AZAMGARH. 28 09185100244 AZ0110652 KISAN AUTO CENTER BOMBAY HOUSE,ROADWAYS, AZAMGARH. -

Hindutva Watch

UNDERCOVER Ashish Khetan is a journalist and a lawyer. In a fifteen-year career as a journalist, he broke several important news stories and wrote over 2,000 investigative and explanatory articles. In 2014, he ran for parliament from the New Delhi Constituency. Between 2015 and 2018, he headed the top think tank of the Delhi government. He now practises law in Mumbai, where he lives with his family. First published by Context, an imprint of Westland Publications Private Limited, in 2020 1st Floor, A Block, East Wing, Plot No. 40, SP Infocity, Dr MGR Salai, Perungudi, Kandanchavadi, Chennai 600096 Context, the Context logo, Westland and the Westland logo are the trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates. Copyright © Ashish Khetan, 2020 ISBN: 9789389152517 The views and opinions expressed in this work are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him, and the publisher is in no way liable for the same. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher. For Zoe, Tiya, Dani and Chris Contents Epigraph Preface Introduction 1 A Sting in the Tale 2 Theatre of Masculinity 3 The Ten-foot-tall Officer 4 Painting with Fire 5 Alone in the Dark 6 Truth on Trial 7 Conspirators and Rioters 8 The Gulbarg Massacre 9 The Killing Fields 10 The Salient Feature of a Genocidal Ideology 11 The Artful Faker 12 The Smoking Gun 13 Drum Rolls of an Impending Massacre 14 The Godhra Conundrum 15 Tendulkar’s 100 vs Amit Shah’s 267 16 Walk Alone Epilogue: Riot after Riot Notes Acknowledgements The Big Nurse is able to set the wall clock at whatever speed she wants by just turning one of those dials in the steel door; she takes a notion to hurry things up, she turns the speed up, and those hands whip around that disk like spokes in a wheel. -

Magazine1-4 Final.Qxd (Page 3)

SUNDAY, MAY 31, 2020 (PAGE 4) BOLLYWOOD BUZZ "Censor board on OTT will be disaster" Gulzar’s Ijaazat Actress Swastika Mukherjee played the role of a troubled work. I have taken a lot of risks in my career which women Sunil Fernandes Patel - in the role of her lifetime). Circumstances, tradi- actors or heroines don’t. How do we better know Sampooran Singh Kalra?". This tions and timidity (on the hero's part) lead him to marry wife who is nearing 40 in Hindi web series Pataal Lok Sudha (Rekha) and just when Mahendra and Sudha are With the advent of OTT, do you think the actors query would have most of our Millennials and Gen Z premiered on Amazon Prime Video recently. Amid the are now exposed to a wide variety of good content, trying to get their marital life on tracks, circumstances characters or roles? scurrying for their smartphones, to Google the correct conspire to lead Maya back in their lives. How does the massive success of the web series which has been Nationally, yes of course. In Kolkata, I feel people still answer - Gulzar - the legendary lyricist, poet, director, trio deal with this situation? Maya isn't your quintessen- produced by Bollywood star Anushka Sharma's Clean have that television hangover which they really need to move screenplay/dialogue writer and winner of the Oscar, tial Bollywood vamp. She respects Mahendra and Sudha's on from because now language is not a barrier. The audience Grammy, Filmfare, National and countless other awards, marriage but finds herself unable to excise all ties with Slate Films Souvik Ghosh caught up with the bold Bengali nowadays has become apt in watching something with sub- in his six decades-long versatile and distinguished career. -

Download Download

"Light Your Cigarette with My Heart's Fire, My Love": Raunchy Dances and a Golden- hearted Prostitute in Bhardwaj's Omkara (2006) Madhavi Biswas, University of Texas Dallas Abstract This essay argues that Omkara (dir. Vishal Bhardwaj, 2006) foregrounds contemporary gender concerns in modern, small-town India, primarily through the film's reformulation of the three female roles in Othello. Billo/Bianca, played by a glamorous, contemporary, female star, gets her own romance and two popular and raunchy song-and-dance tracks in Omkara. These dance tracks are a peculiar mixture of traditional folk Nautanki and identifiable Bollywood masala "item numbers," whose layered lyrics have been penned by Gulzar, a well-known poet, lyricist, scriptwriter, and ex-film-director who closely collaborates with Bhardwaj. The essay argues for the recognition of the songs in Omkara as a parallel narrative that intertwines with and intersects the central narrative of the plot, inflecting it with a range of cultural and social intertexts, along with a dash of metatextual flavor. The article examines how the two song-and-dance sequences by Billo/Bianca in the film use the familiar tropes of the "courtesan" figure of Hindi films and draw upon traditional folk-theater — reflecting both its local poetry and its vulgarity — to evoke a new kind of verbal and visual "realism" that intertwines Bollywood glamor with local histories. Omkara, with its big budget stars, glossy production values, and popular song- and-dance numbers interspersing the narrative — elements that are often associated with the "Bollywood" style of Hindi cinema — is the most obviously commercial of Vishal Bhardwaj's three Shakespearean adaptations.