D4.2 Europeanisation of National Policy Dialogues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nuclear Energy Education and Training in France

NUCLEAR ENERGY IN FRANCE France now obtains about 78 percent of its electricity from nuclear energy, generated by 58 highly standardized pressurized-water reactors (PWR) at 19 locations. The operation of these reactors has provided extensive feedback on safety, cost effectiveness, proficiency, and public outreach. In producing nuclear energy, France has always relied on a closed- fuel-cycle approach, including reprocessing of the spent nuclear fuel, an approach deemed essential to conserve uranium resources and to manage the ultimate waste products efficiently and selectively. Recent years have confirmed the central role that safe and sustain- able nuclear energy plays in the French electricity supply with addi- tional renewable energy technologies. France is pursuing the development of fourth-generation fast-neutron reactors, as well as a continuing investigation of improved methods for the separation and transmutation of high-level, long-lived nuclear waste. Scientific and AERIAL VIEW OF LA HAGUE engineering research into the safe and appropriate geological REPROCESSING PLANT disposal of radioactive waste products is also ongoing. ©AREVA/J-M.TAILLAT In May 2006, the board of Electricité de France (EDF) approved the construction of a new 1650 MWe European Pressurized Reactor (EPR) at Flamanville near the tip of Normandy. In 2009, the French government strengthened its commitment to pressurized-water reactors by endorsing the construction of a second EPR unit at Penly, near Dieppe. NEW CHALLENGES AND NEW REQUIREMENTS In its continuing use of nuclear power, France faces numerous chal- lenges, including the operation and maintenance of its existing array of reactors, waste management, the decommissioning of obsolete reactors, and research and development for future nuclear systems. -

From the History of Sources and Sectors to the History of Systems and Transitions

Journal of Energy History Revue d’histoire de l’énergie AUTHOR Geneviève Massard- From the history of sources and Guilbaud sectors to the history of systems École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales and transitions: how the history of [email protected] energy has been written in France POST DATE and beyond* 04/12/2018 ISSUE NUMBER Abstract JEHRHE #1 This historiographical essay shows how historians have dealt with SECTION energy since the beginning of the 20th c. and until today. During the Special issue two first third of the 20th c., only a handful of authors have tried THEME OF THE SPECIAL ISSUE to give an overview of humans made use of the energy existing all For a history of energy around them over centuries. Historians of the last decades of the KEYWORDS 20th centuries were interested in specific energy sources as well as Transition, Production, in energy sectors. More recently, tendency has come back to con- Consumption, Environment, sidering energy as a whole, studying energetic systems and the Regime transitions between them. There has been so far no consensus on DOI the nature and the stakes involved in the past transitions. in progress Plan of the article TO CITE THIS ARTICLE → Historians and energy, initial research Geneviève Massard- → Studies by energy source and sector Guilbaud, “From the history → Wood, water, and wind of sources and sectors to → Fossil energies the history of systems and → Electricity transitions: how the history → Studies of energy systems and transitions of energy has been written → Conclusion: writing the history of energy during a time of global in France and beyond”, warming Journal of Energy History/ Revue d’Histoire de l’Énergie [Online], n°1, published 04 December 2018, URL: http:// energyhistory.eu/node/88. -

Renewable Energy 2021

Renewable Energy 2021 A practical cross-border insight into renewable energy law First Edition Featuring contributions from: Bracewell (UK) LLP Gómez-Acebo & Pombo Abogados POSSER SPIETH WOLFERS & PARTNERS Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr Inc (CDH) Gonzalez Calvillo The Law Firm of Wael A. Alissa in Dentons & Co. Jones Day association with Dentons & Co. Doulah & Doulah Mazghouny & Co UMBRA – Strategic Legal Solutions DS Avocats Nishimura & Asahi Wintertons European Investment Bank Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP Table of Contents Expert Chapters Renewable Energy Fuelling a Green Recovery 1 Mhairi Main Garcia, Dentons & Co. Trends and Developments in the European Renewable Energy Sector 5 from a Public Promotional Banking Perspective Roland Schulze & Matthias Löwenbourg-Brzezinski, European Investment Bank Q&A Chapters Australia Saudi Arabia 11 Jones Day: Darren Murphy, Adam Conway & 76 The Law Firm of Wael A. Alissa in association with Prudence Smith Dentons & Co.: Mahmoud Abdel-Baky & Mhairi Main Garcia Bangladesh 19 Doulah & Doulah: A.B.M. Nasirud Doulah & South Africa Dr. Amina Khatoon 83 Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr Inc (CDH): Jay Govender, Emma Dempster, Tessa Brewis & Alecia Pienaar Egypt 26 Mazghouny & Co: Donia El-Mazghouny Spain 91 Gómez-Acebo & Pombo Abogados: Luis Gil Bueno & Ignacio Soria Petit France 33 DS Avocats: Véronique Fröding & Stéphane Gasne United Arab Emirates 99 Dentons & Co.: Mhairi Main Garcia & Germany Stephanie Hawes 41 POSSER SPIETH WOLFERS & PARTNERS: Dr. Wolf Friedrich Spieth, Niclas Hellermann, Sebastian Lutz-Bachmann & Jakob von Nordheim United Kingdom 109 Bracewell (UK) LLP: Oliver Irwin, Kirsty Delaney, Nicholas Neuberger & Robert Meade Indonesia 48 UMBRA – Strategic Legal Solutions: Kirana D. Sastrawijaya, Amelia Rohana Sonang, USA Melati Siregar & Junianto James Losari 117 Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP: Mona E. -

Energy Security Concerns Versus Market Harmony: the Europeanisation of Capacity Mechanisms

Politics and Governance (ISSN: 2183–2463) 2019, Volume 7, Issue 1, Pages 92–104 DOI: 10.17645/pag.v7i1.1791 Article Energy Security Concerns versus Market Harmony: The Europeanisation of Capacity Mechanisms Merethe Dotterud Leiren 1,*, Kacper Szulecki 2, Tim Rayner 3 and Catherine Banet 4 1 CICERO Center for International Climate Research, 0349 Oslo, Norway; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Political Science, University of Oslo, 0851 Oslo, Norway; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, University of East Anglia, Norwich, NR4 7TJ, UK; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Scandinavian Institute of Maritime Law, University of Oslo, 0162 Oslo, Norway; E-Mail: [email protected] * Corresponding author Submitted: 21 October 2018 | Accepted: 7 December 2018 | Published: 28 March 2019 Abstract The impact of renewables on the energy markets–falling wholesale electricity prices and lower investment stability–are apparently creating a shortage of energy project financing, which in future could lead to power supply shortages. Govern- ments have responded by introducing payments for capacity, alongside payments for energy being sold. The increasing use of capacity mechanisms (CMs) in the EU has created tensions between the European Commission, which encour- ages cross-country cooperation, and Member States that favour backup solutions such as capacity markets and strategic reserves. We seek to trace the influence of the European Commission on national capacity markets as well as learning between Member States. Focusing on the United Kingdom, France and Poland, the analysis shows that energy security concerns have been given more emphasis than the functioning of markets by Member States. -

Philippe2016-Energy Transition Policies in France and Their Impact

Energy transition policies in France and their impact on electricity generation – DRAFT VERSION – Sébastien Philippe [email protected] Nuclear Futures Laboratory Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Princeton University January 12, 2016 Abstract: France experienced recently the important transformation of its energy and environmental policy through the entry into force of the Energy Transition for Green Growth Act and the recent Paris agreement between the parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. In this paper, we study the economic implications of this transformation on electricity generation. In particular, we focus on the economic rationale of conducting France energy transition with an extraordinary portfolio of market-based policies including feed-in tariffs, auctions, carbon pricing and the European Union cap and trade scheme. We find that such approach can produce more economic inefficiencies than the sole application of a carbon pricing policy. We emphasized, however, that the uncertainties in the ability of the current wholesale and the newly created capacity markets to address both economical and physical requirements of security of supply, favored the continuation of conservative (and risk adverse) policies. Finally, we discuss the structure of the future electricity mix expected to emerge from the current policies and question its social optimality. Introduction In December of 2015, the parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change agreed during the 21st session -

Energy & Society Conference

Energy & Society Conference March 22 - 24, 2012, Institute of Social Sciences (ICS-UL), Lisbon, Portugal Detailed program Thursday, 22th March 14:30 – 15:00 – Welcome and introduction (Auditório) Jorge Vala, director of ICS-UL Luísa Schmidt, ICS-UL Introduction of the keynote speaker: Françoise Bartiaux, UCL 15:00 – 16:30 - Keynote presentation: Harold Wilhite, Univ. Oslo: “The space accorded to the social science of energy consumption is (finally) expanding: Where can we draw inspiration?” 16:30 – 17:00 - Coffee break (fair trade) 17:00 – 18:30 - Parallel thematic sessions Thematic session 1 (Auditório) Energy consumption practices Chair: Luísa Schmidt, ICS-UL Bartiaux, Françoise & Reátegui Compartmentalisation or domino effects between ‘green’ Salmón, Luis consumers’ practices? Some topics of practice theories observed with an Internet survey Butler, Catherine Climate Change, Social Change and Social Reproduction: Exploring energy demand reduction through a biographical lens Battaglini, Elena Challenging the framing of ‘space’ in the Theory of Practice. Research findings from a European study on Energy-efficient renovation’s practices in the residential sector Berker, Thomas Kicking the habit. Identifying crucial themes of a sociology of energy sensibilities Fonseca, Susana & Nave, From structural factors to individual practices: reasoning on the main Joaquim Gil paths for action on energy efficiency Petersen, Lars Kjerulf Autonomy and proximity in household heating practices – the case of wood burning stoves Roudil, Nadine, Flamand, Energy housing consumption. Practices, rationalities and motivations Amélie & Douzou, Sylvie of inhabitants Huebner, Gesche, Cooper, Understanding energy consumption in domestic households Justine & Jones, Keith 1 Thematic session 2 (Sala polivalente) Energy policies and sustainability Chair: Júlia Seixas, FCT-UNL Beischl, Martin The Energy Community of South East Europe and its lacking social dimension. -

Sizing and Economic Assessment of Photovoltaic and Diesel Generator for Rural Nigeria

The International Journal of Engineering and Science (IJES) || Volume || 6 || Issue || 10 || Pages || PP 10-17 || 2017 || ISSN (e): 2319 – 1813 ISSN (p): 2319 – 1805 Sizing and Economic Assessment of Photovoltaic and Diesel Generator for Rural Nigeria # * # Abaka J. U., Iortyer H.A., Ibraheem T. B. #Energy Commission of Nigeria [email protected] --------------------------------------------------------ABSTRACT----------------------------------------------------------- Sizing and economic assessment of solar photovoltaic (PV) and diesel power generators for Igu village in Bwari, FCT-Abuja was carried out. Load survey of the site was carried out in order to get the actual solar radiation (using full PV, HT ITALIA 2010 analyzer), village load requirement and other sundry data (using structured questionnaire). An off-grid solar PV design was done for the village. Life cycle cost analysis was used to assess the economic viability of the PV and diesel generating systems respectively using Music Macro Language (MML) to allow for the calculation and comparison of the levelised costs of electricity generation for the two systems. The total load of Igu village was estimated to be 140.24kW (Losses and tolerance inclusive). The system components computed include; 1194 PV modules of 235W, 351 batteries of 375Ah, 68 charge controllers of 60A and 14 inverters of 10kW each covering 3346.1m2 area of installation. The PV system cost is N268, 000,000.00. Two diesel generators of 350KVA costing N39, 433,419.00, each operating at 12 hours and ten (10) years apart within an estimated period of twenty (20) years, were also sized to meet this load requirement. It was discovered, using the life cycle analysis method, that the PV system has a lower levelised cost of electricity production ranging from 26.52 N/kWh in the first year to about 35.82 N/kWh in the twentieth year compared to the 81.27 N/kWh and 143.34 N/kWh in the first and twentieth years respectively for the diesel generator. -

What Can EU Policy Do to Support Renewable Electricity in France? Oliver Sartor (IDDRI)

N°06/16 APRIL 2016 | CLIMATE What can EU policy do to support renewable electricity in France? Oliver Sartor (IDDRI) ELECTRICITY IS A CRITICAL ELEMENT OF ACHIEVING THE EU’S 2030 RENEWABLE ENERGY TARGETS Under the 2030 Climate and Energy Package, the European Union has set itself a target of increasing the share of renewable energy from to 27%. Electricity will play a key role in achieving these goals, with the share of renewable power projected to increase to around 47% of the electricity mix by 2030. While electricity is only one part of the energy system, elec- tricity is therefore a vital sub-sector of the EU’s renewable energy strategy to 2030. FRANCE IS A CRITICAL PLAYER FOR MEETING THE EU’S 2030 RENEWABLE ELECTRICITY GOALS As the second largest energy consumer in Europe, and with relatively ambitious national goals of achieving 32% renewable energy and 40% renewable electricity (RES-E) by 2030, France will be critical to achieving the EU’s objectives. As the most interconnected electricity market in Europe, France’s approach to renewable electricity will also influence the redesign of electricity markets to cope with higher shares of variable RES-E in its region. Facilitating the efficient deployment and integration of renewable electricity in France is therefore an important sub-chapter of European renewable energy policy going forward. THE EU CAN FACILITATE THE ACHIEVEMENT OF FRANCE’S RES-E TARGETS IN SEVERAL WAYS The integration of higher shares of renewable electricity in France is a significant domestic policy challenge. But EU can take a number steps to facilitate the achievement of France’s goals. -

Maurice Barrès and the Fate of Boulangism: the Political Career Of

This dissertation has been 65—3845 microfilmed exactly as received DOTY, Charles Stewart, 1928— MAURICE BARR^S AND THE EATE OF BOULANG- BM: THE POLITICAL CAREER OF MAURICE BARRES (1888-1906). The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1964 History, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Copyright by Charles Stewart Doty 1965 MAURICE BARRES AND THE FATE OF BOULANGISM: THE POLITICAL CAREER OF MAURICE BARRES (1888-1906) DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Charles Stewart Doty, A.B., M.A. The Ohio State University 1964 Approved by Department of History V ita September 8, 1928 Born - Fredonia, Kansas 1950 ..................... A. B., Washburn Municipal University, Topeka, Kansas 1953-1954 • • • Research Assistant, Department of History, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 1955 ..................... M.A., University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 1957-1960 . Graduate Assistant, Department of History, The Ohio S ta te U niv ersity, Columbus, Ohio I960 ...................... Part-time Instructor, Department of History, Denison University, Granville, Ohio 1960-1961 . Part-time Instructor, Department of History, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1961-1964 . Instructor, Department of History, Kent S ta te U niversity, Kent, Ohio Fields of Study Major Field: History Studies in Modern Europe, 1789-Present, Professors Andreas Dorpalen, Harvey Goldberg, and Lowell Ragatz Studies in Renaissance and Reformation, Professor Harold J. Grimm Studies in United States, 1850-Present, Professors Robert H. Brem- ner, Foster Rhea Dulles, Henry H. Simms, and Francis P. Weisenburger i i table of contents Page INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER I . -

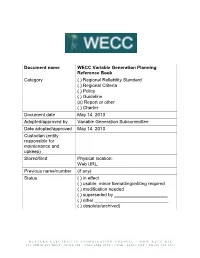

Document Name WECC Variable Generation Planning Reference

Document name WECC Variable Generation Planning Reference Book Category ( ) Regional Reliability Standard ( ) Regional Criteria ( ) Policy ( ) Guideline (x) Report or other ( ) Charter Document date May 14, 2013 Adopted/approved by Variable Generation Subcommittee Date adopted/approved May 14, 2013 Custodian (entity responsible for maintenance and upkeep) Stored/filed Physical location: Web URL: Previous name/number (if any) Status ( ) in effect ( ) usable, minor formatting/editing required ( ) modification needed ( ) superseded by _____________________ ( ) other _____________________________ ( ) obsolete/archived) WESTERN ELECTRICITY COORDINATING COUNCIL • WWW.WECC.BIZ 155 NORTH 400 WEST • SUITE 200 • SALT LAKE CITY • UTAH • 84103- 1114 • PH 801.582.0353 May 14, 2013 2 WECC Variable Generation Planning Reference Book A Guidebook for Including Variable Generation in the Planning Process Volume 2: Appendices Version 1 May 14, 2013 WESTERN ELECTRICITY COORDINATING COUNCIL • WWW.WECC.BIZ 155 NORTH 400 WEST • SUITE 200 • SALT LAKE CITY • UTAH • 84103- 1114 • PH 801.582.0353 May 14, 2013 3 WESTERN ELECTRICITY COORDINATING COUNCIL • WWW.WECC.BIZ 155 NORTH 400 WEST • SUITE 200 • SALT LAKE CITY • UTAH • 84103- 1114 • PH 801.582.0353 May 14, 2013 4 Project Lead Dr. Yuri V. Makarov, Chief Scientist – Power Systems, (Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) Western Electricity Coordinating Council (WECC) Project Manager Matthew Hunsaker, Renewable Integration Manager Contributors Art Diaz-Gonzalez, Supervisory Power System Dispatcher, Western Area Power Administration (WAPA) Ross T. Guttromson, PE, MBA, Manager Energy Storage, Sandia National Laboratory Dr. Pengwei Du, Research Engineer, PNNL Dr. Pavel V. Etingov, Senior Research Engineer, PNNL Dr. Hassan Ghoudjehbaklou, Senior Transmission Planner, San Diego Gas & Electric (SDG&E) Dr. Jian Ma, PE, PMP, Research Engineer, PNNL David Tovar, Principal Electrical Systems Engineer, El Paso Electric Company Dr. -

INFORSE-Europe: Seminars, Visions, Projects EU Energy & Climate

Newsletter for INFORSE International Network for SustainableNEWS Energy No. 60, April 2008 Women - Energy - Climate Theme: Global Influence & Local Efforts INFORSE-Europe: Seminars, Visions, Projects EU Energy & Climate Packet Editorial More Women Sustainable Energy News Needed for INFORSE, the NGO network that produces ISSN 0908 - 4134 Decisions this newsletter, has shown that technically it Published by: is possible to have a 100% renewable energy INFORSE-Europe Break the supply by 2050 or earlier. We, together with the “Glass NGO community, work to spread the required Ceiling” on knowledge and to secure the political will for Sustainability International Network for the transition. There is a process ahead. Renew- Sustainable Energy (INFORSE) able-energy and energy-efficiency solutions are is a worldwide NGO network Women are underrepresented in decision- available and their use is increasing. The EU formed at the Global Forum in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1992. making. Even though women got voting rights leaders have set targets, and the EU Commis- in Finland in 1907 and throughout Europe in the sion has proposed legal frameworks by which Editorial Address: following years, the number of women in the to achieve them. The change has started, but it Sustainable Energy News INFORSE-Europe parliaments of EU countries is still only 24 % on needs to be made faster. Gl. Kirkevej 82, DK-8530 average. In the world the average is only 17%. Hjortshøj, Denmark. It is also well known that women still get lower I think there are two main scenarios for the future: T: +45-86-227000 wages for the same job; and the typical “woman Either there will be an environmental catastro- F: +45-86-227096 E: [email protected] jobs” like teaching and nursing pay less than phe or there will be a cleaner planet supplied W: http://www.inforse.org/ most “men jobs”. -

The Transformations of the Major French Energy Players Induced By

DEGREE PROJECT IN INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING AND MANAGEMENT, SECOND CYCLE, 30 CREDITS STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN 2017 The transformations of the major French energy players induced by the energy transition, the emergence of new actors, digitization from an organizational, structural, cultural point of view. The transformations of major energy players accompanied by the weave consulting firm. HÉLÈNE PAPILLAUD KTH ROYAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SCHOOL OF INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING AND MANAGEMENT Papillaud Hélène 2 Papillaud Hélène ABSTRACT Today, the current energy situation is particularly difficult for major French energy players. Indeed, they have to face high energy prices - that go up and down -, have to look at renewable energies – by integrating them into their energy mix or into their distribution model - and digitize to manage their customer relations - customers’ behavior has changed and utilities have to adapt to this new behavior. They must respond to these problems while being confronted with the arrival of new entrants to the energy market: multiplication of energy players but also appearance of players in telecommunications, data…. To cope with this energy revolution, the great French utilities have no choice but to transform themselves. They must evolve technologically, digitally and also organically, structurally and culturally. The strategy of major historical energy players is therefore completely redesigned in order to give them the possibility of remaining competitive in their market and not losing their place in this revolution. They have to adapt to these new challenges and to transform themselves. Major French energy players, as ENGIE, EDF and RTE, have already started to imagine and implement new strategies to face the current energy challenges.