Whitewater-Baldy Complex Fire Review Gila National Forests USDA Forest Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The AILING GILA WILDERNESS

The AILING GILA WILDERNESS A PICTORIAL REVIEW The AILING GILA WILDERNESS A PICTORIAL REVIEW ~ Gila Wilderness by RONALD J. WHITE Division Director M.S. Wildlife Science, B.S. Range Science Certified Wildlife Biologist Division of Agricultural Programs and Resources New Mexico Department of Agriculture December 1995 ACknoWledgments Many people who live in the vicinity of the Gila National Forest are concerned about the degraded condition of its resources. This document resulted from my discussions with some of them, and the conclusion that something must be started to address the complex situation. Appreciation is extended to the participants in this project, who chose to get involved, and whose assistance and knowledge contributed significantly to the project. Their knowledge ofthe country, keen observations, and perceptive interpretations of the situation are unsurpassed. As a bonus, they are a pleasure to be around. Kit Laney - President, Gila Permittee's Association, and lifetime area rancher, Diamond Bar Cattle Co. Matt Schneberger - Vice President, Gila Permittee's Association, and lifetime area rancher, Rafter Spear Ranch. Becky Campbell Snow and David Snow - Gila Hot Springs Ranch. Becky is a lifetime area guide and outfitter. The Snows provided the livestock and equipment for both trips to review and photograph the Glenn Allotment in the Gila Wilderness. Wray Schildknecht - ArrowSun Associates, B.S. Wildlife Science, Reserve, NM. D. A. "Doc" and Ida Campbell, Gila Hot Springs Ranch, provided the precipitation data. They have served as volunteer weather reporters for the National Weather Service Forecast Office since 1957, and they are longtime area ranchers, guides, and outfitters. Their gracious hospitality at headquarters was appreciated by everyone. -

Gila National Forest Fact Sheet

CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY Because life is good. GILA NATIONAL FOREST The Gila National Forest occupies 3.3 million acres in southwestern New Mexico and is home to the Mexican spotted owl, Mexican gray wolf, Gila chub, southwestern willow flycatcher, loach minnow, and spikedace. The forest also encompasses the San Francisco, Gila, and Mimbres Rivers, and the scenic Burros Mountains. In the 1920s, conservation pioneer Aldo Leopold persuaded the Forest Service to set aside more than half a million acres of the Gila River’s headwaters as wilderness. This wild land became the nation’s first designated wilderness Photo © Robin Silver — the Gila Wilderness Area — in 1924. The Gila National Forest is home to threatened Mexican spotted owls and many other imperiled species. n establishing the Gila Wilderness Area, the Gila The Gila National Forest’s plan by the numbers: National Forest set a precedent for protection Iof our public lands. Sadly, it appears that • 114,000: number of acres of land open to safeguarding the Gila for the enjoyment of future continued destruction; generations is no longer management’s top priority. • 4,764: number of miles of proposed motorized On September 11, 2009, the Gila National Forest roads and trails in the Gila National Forest, equal to released its travel-management plan, one of the worst the distance from Hawaii to the North Pole; plans developed for southwestern forests. Pressure • $7 million: road maintenance backlog accumulated from vocal off-road vehicle users has overwhelmed the by the Gila National Forest; Forest Service, which has lost sight of its duty to protect • less than 3 percent: proportion of forest visitors this land for future generations. -

Butch Cassidy Roamed Incognito in Southwest New Mexico

Nancy Coggeshall I For The New Mexican Hideout in the Gila Butch Cassidy roamed incognito in southwest New Mexico. Hideout in the Gila utch Cassidy’s presence in southwestern New Mexico is barely noted today. Notorious for his successful bank Butch Cassidy roamed and train robberies at the turn of the 20th century, incognito in southwest Cassidy was idealized and idolized as a “gentleman out- New Mexico wilderness Blaw” and leader of the Wild Bunch. He and various members of the • gang worked incognito at the WS Ranch — set between Arizona’s Blue Range and San Carlos Apache Reservation to the west and the Nancy Coggeshall rugged Mogollon Mountains to the east — from February 1899 For The New Mexican until May 1900. Descendants of pioneers and ranchers acquainted with Cassidy tell stories about the man their ancestors knew as “Jim Lowe.” Nancy Thomas grew up hearing from her grandfather Clarence Tipton and others that Cassidy was a “man of his word.” Tipton was the foreman at the WS immediately before Cassidy’s arrival. The ranch sits at the southern end of the Outlaw Trail, a string of accommodating ranches and Wild Bunch hideouts stretching from Montana and the Canadian border into Mexico. The country surrounding the WS Ranch is forbidding; volcanic terrain cleft with precipitously angled, crenelated canyon walls defies access. A “pretty hard layout,” local old-timer Robert Bell told Lou Blachly, whose collection of interviews with pioneers — conducted PROMIENT PLACES - between 1942 and 1953 — are housed at the University of New OUTLAW TRAIL Mexico. What better place to dodge the law? 1. -

LIGHTNING FIRES in SOUTHWESTERN FORESTS T

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. LIGHTNING FIRES IN SOUTHWESTERN FORESTS t . I I LIGHT~ING FIRES IN SOUTHWESTERN FORESTS (l) by Jack S. Barrows Department of Forest and Wood Sciences College of Forestry and Natural Resources Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO 80523 (1) Research performed for Northern Forest Fire Laboratory, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station under cooperative agreement 16-568 CA with Rocky Mountain For est and Range Experiment Station. Final Report May 1978 n LIB RARY COPY. ROCKY MT. FO i-< t:S'f :.. R.l.N~ EX?f.lt!M SN T ST.A.1101'1 . - ... Acknowledgementd r This research of lightning fires in Sop thwestern forests has been ? erformed with the assistan~e and cooperation of many individuals and agencies. The idea for the research was suggested by Dr. Donald M. Fuquay and Robert G. Baughman of the Northern Forest Fire Laboratory. The Fire Management Staff of U. S. Forest Service Region Three provided fire data, maps, rep~rts and briefings on fire p~enomena. Special thanks are expressed to James F. Mann for his continuing assistance in these a ctivities. Several members of national forest staffs assisted in correcting fire report errors. At CSU Joel Hart was the principal graduate 'research assistant in organizing the data, writing computer programs and handling the extensive computer operations. The initial checking of fire data tapes and com puter programming was performed by research technician Russell Lewis. Graduate Research Assistant Rick Yancik and Research Associate Lee Bal- ::. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument Foundation Document

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument New Mexico Contact Information For more information about the Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument Foundation Document, contact: [email protected] or (575) 536-9461 or write to: Superintendent, Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, HC 68 Box 100, Silver City, NM 88061 Purpose Significance Significance statements express why Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument resources and values are important enough to merit national park unit designation. Statements of significance describe why an area is important within a global, national, regional, and systemwide context. These statements are linked to the purpose of the park unit, and are supported by data, research, and consensus. Significance statements describe the distinctive nature of the park and inform management decisions, focusing efforts on preserving and protecting the most important resources and values of the park unit. As the only unit of the national park system dedicated to the Mogollon • Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument protects the largest culture, the purpose of GILA CLIFF known Mogollon cliff dwellings site and interprets for the DWELLINGS NATIONAL MONUMENT is to public well-preserved structures built more than 700 years protect, preserve, and interpret the ago. Architectural features and associated artifacts are cliff dwellings and associated sites and exceptionally preserved within the natural caves of Cliff artifacts of that culture, set apart for Dweller Canyon. its educational and scientific interest • The TJ site of the monument includes one of the last and public enjoyment within a remote, unexcavated, large Mimbres Mogollon pueblo settlements pristine natural setting. -

Trails in the Gila Wilderness Area Recently

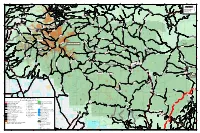

R. 20 W. R. 19 W. R. 18 W. R. 17 W. R. 16 W. R. 15 W. R. 14 W. R. 13 W. R. 12 W. R. 11 W. 108°45'W 108°30'W 108°15'W 108°0'W E I D G Spring Upper R 10 C Negrito A R B Canyon 9 a n 5 Black 9J Long Cyn. Burnt 12 B Pine 4065A 7 8 Doagy n Barlow Tank 23 o T 4 l Houghton F y 4 1 e Pasture 0 a 1 n y 6 1:63,360 2 6 Reserve Ranger District RD anyo 12 o Steer 1 k Quaking Aspen Cr. 6 C 6 3 949 97 5 3 Corduroy Tank 4 Tank D n Gooseb Cabin Tank I 4 J c Tank 4 0 Doagy Spr. n ea a erry 1 11 99 5 dm a Tank 6 1 4 Arroyo Well 1 6 X an L 40 k 10 1 in = 1 miles C Tank 6 t 40 9 Houghton Corduroy Corral Spr. 5 s Barlow 6 Negrito R 8 (printed on 36" x 54" landscapeDoagie Spr. layout) 0 Dead Man Spr. o S 0 M 7 S 4 L a C U a 12 Water Well Beechnut Tank Basin Hogan Spr. va a Mountain 12 1 10 11 406 Bill Lewis S Deadman 6 Barlow ep g n 11 6 South n 9 Z De e n B 10 0 7 8 n Pine 4 C anyo y 9 r 12 0 0.25 0.5 1 1.5 2 Tank anyo Cabin 9 o 9 Tank 8 8583 4 B 11 g Bonus Basin C 1 n 12 7 Fork Spr. -

A Path Through the Wilderness: the Story of Forest Road

A Path Through the Wilderness: The Story of Forest Road 150 Gila National Forest Erin Knolles Assistant Forest Archeologist March 2016 1 National Forest System Road 150 [commonly referred to as Forest Road (FR) 150], begins within the confines of the Gila National Forest and stretches north about 55 miles from NM 35 near Mimbres past Beaverhead Work Center to NM 163 north of the Gila National Forest boundary. FR 150 is the main road accessing this area of the Gila National Forest. Its location between two Wilderness Areas, Aldo Leopold and the Gila, makes it an important corridor for public access, as well as, administrative access for the Gila National Forest. Forest Road 150: The Name and a Brief History FR150 has been known by several names. The road was first called the North Star Road by the residents of Grant County and the U.S. Military when it was constructed in the 1870s.1 Today, the route is still called the North Star Road and used interchangeably with FR 150. Through most of the 20th century, FR 150 was under New Mexico state jurisdiction and named New Mexico (NM) 61.2 Of interest is that topographical maps dating to at least 1980, list the road as both NM 61 and FR 150.3 This is interesting because, today, it is common practice not to give roads Forest Service names unless they are under the jurisdiction of the Forest Service. In addition, the 1974 Gila National Forest Map refers to the route as FR 150.4 There is still some question when the North Star Road and NM 61 became known as FR 150. -

Trails in the Aldo Leopold & Gila Wilderness Areas Recently

R. 19 W. R. 18 W. R. 17 W. R. 16 W. R. 15 W. R. 14 W. R. 13 W. R. 12 W. R. 11 W. R. 10 W. R. 9 W. R. 8 W. 108°45'W 108°30'W 108°15'W 108°0'W 107°45'W 4 Old Waterman 4 24 0 4063C 22 Greer Tank 22 23 6 20 21 26 I 0 21 3 24 19 27 Place 8 20 5 G 22 23 28 05 24 19 l 20 21 D 0 29 1:63,360 Silver 4056R 22 23 4 40 8 o 4 19 R Wolf Hollow 1 30 21 5 Adam o 0 D 0 25 20 8 V h 23 24 e 59 Thumb Taylor 19 3 19 H Teacher c 6 R 26 Franks 1 in = 1 miles Peak S Snow 21 22 Angelo v Bull Ranger Tank 0 Moore Hoague 3 Loco r U Waterman Gilita Tank Tank 20 e e C Tank Peak 3 73 27 Ranch C 19 F g Pass 4T 26 S 0 (printed on 36" x 68" landscape layout) 7149 n op Lake Lake Mtn. Harrix s 6 y 27 ca 4 28 Ranch p 4058J e n 021 40 ro 28 8294 les o Cabin er 137 Turkey a Tank 1 u 29 25 108 y n C Well R R e d 30 29 46 Canyo Snow Tank Cabin Little k 4 r 25 Doubtful Spr. Miner n r. Cienega k4 a o 26 30 0 0.25 0.5 1 1.5 2 4056Q 71 c T 4 L 2 Canyon Jack Tank C 28 27 Alvin Spr. -

Trails in the Gila Wilderness Area Recently Maintained & Cleared

R. 20 W. R. 19 W. R. 18 W. R. 17 W. R. 16 W. R. 15 W. R. 14 W. R. 13 W. R. 12 W. R. 11 W. 108°45'W 108°30'W 108°15'W 108°0'W G E R I D Spring Black Steer Arroyo Well 10 C Upper A R Pine Canyon 9 Corduroy a n 5 12 B 4065A 7 8 Doagy n J o T 4 Houghton y Barlow 9 1 e 0 Tank 1 n 23 2 y 6 anyo 12 Corral 1:63,360 o k 6 C 4 3 949 5 3 Corduroy Doagy 4 Dead n Gooseb I 4 J 4 4066F n a erry 1 11 Tank 99 5 Hogan a 6 1 1 6 L 40 10 Spr. 1 in = 1 miles X C Burnt Negrito Tank Spr. Tank Long Man Spr. t 4 9 6 C 0 Houghton 150 Barlow 5 Spr. s Bill 6 Negrito 8 5 (printed on 36" x 54" landscape layout) o 0 Cyn. S 9 119 0 Cabin Pasture M 7 5 Doagie Spr. Hogan S 9 4 19 L av C Q U 1 12 Water Well Basin 7 a a 5 Lewis u Mountain 12 10 11 Barlow Dea eep g n a Tank 11 Tank 6 South Fork Spr. S 8 9 Deadman Beechnut Tank dm D e n B 0 k 10 0 7 n Spr. an Pine 4 Canyo y 9 r 12 Bonus 0 0.25 0.5 1 1.5 2 Tank yo 9 Tank 8 i B an o 9 4 n 8583 4 11 Basin C 1 n 5 12 7 g a 9 10 Tank Tank r. -

Coronado National Forest Potential Wilderness Area Evaluation Report

United States Department of Agriculture Coronado National Forest Potential Wilderness Area Evaluation Report Forest Service Southwestern Region Coronado National Forest July 2017 Potential Wilderness Area Evaluation Report In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. -

Gila National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 01/01/2007 to 03/31/2007 Gila National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Aerial Application of Fire - Fuels management In Progress: Expected:07/2007 08/2007 Christopher Wehrli Retardant 215 Comment period legal 202-205-1332 EA notice 07/28/2006 fire [email protected] *NEW LISTING* Description: The Forest Service proposes to continue the aerial application of fire retardant to fight fires on National Forest System lands. An environmental analysis will be conducted to prepare an Environmental Assessment on the proposed action. Web Link: http://www.fs.fed.us/fire/retardant/index.html. Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. Nation Wide. Gila National Forest, Forestwide (excluding Projects occurring in more than one Forest) R3 - Southwestern Region Management Indicator Species - Land management planning Completed Actual: 09/29/2006 01/2007 Debby Hyde-Sato EA 505-388-8483 [email protected] Description: Revise Forest Plan Management Indicator Species list Location: UNIT - Gila National Forest Units. STATE - New Mexico. COUNTY - Catron, Grant, Hidalgo, Sierra. LEGAL - T1S-T10N, T6S-18S, R1-13W, R30E-32E. Forest-wide. University of Arizona Shrew - Special use management On Hold N/A N/A John Baumberger Research 505-388-8238 DM [email protected] Description: Research on shrews Location: UNIT - Gila National Forest All Units. STATE - New Mexico. COUNTY - Catron, Grant, Sierra. LEGAL - Forest-wide.