Derek Attridge, 'Auden and Britten's Night Mail: Rap Before Rap'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter 32

The W. H. Auden Society Newsletter Number 32 ● July 2009 Memberships and Subscriptions Annual memberships include a subscription to the Newsletter: Contents Individual members £9 $15 Katherine Bucknell: Edward Upward (1903-2009) 5 Students £5 $8 Nicholas Jenkins: Institutions and paper copies £18 $30 Lost and Found . and Offered for Sale 14 Hugh Wright: W. H. Auden and the Grasshopper of 1955 16 New members of the Society and members wishing to renew should David Collard: either ( a) pay online with any currency by following the link at A New DVD in the G.P.O. Film Collection 18 http://audensociety.org/membership.html Recent and Forthcoming Books and Events 24 or ( b) use postal mail to send sterling (not dollar!) cheques payable to “The W. H. Auden Society” to Katherine Bucknell, Memberships and Subscriptions 26 78 Clarendon Road, London W11 2HW, Receipts available on request. A Note to Members The W. H. Auden Society is registered with the Charity Commission for England and Wales as Charity No. 1104496. The Society’s membership fees no longer cover the costs of printing and mailing the Newsletter . The Newsletter will continue to appear, but The Newsletter is edited by Farnoosh Fathi. Submissions this number will be the last to be distributed on paper to all members. may be made by post to: The W. H. Auden Society, Future issues of the Newsletter will be posted in electronic form on the 78 Clarendon Road, London W11 2HW; or by Society’s web site, and a password that gives access to the Newsletter e-mail to: [email protected] will be made available to members. -

California State University, Northridge Department of Cinema and Television Arts

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND TELEVISION ARTS CTVA 416: The Documentary Tradition Spring 2019 3 units #10815 Classroom: Manzanita Hall 103 Meeting time: Tuesdays, 7 - 9:45pm Class Website http://www.csun.edu/~med61203 Professor: María Elena de las Carreras, Ph.D. Office: Manzanita Hall 194 Office Hour: Thursdays, 6pm Main Office Phone – for messages: (818) 677 3192 E-mail: [email protected] Focus of the Course This course covers the history and development of the documentary film from the genre’s beginnings to the present day. It will examine major films, movements, filmmakers and various types of documentaries from numerous national and cultural contexts. As the course progresses, it will become evident that there are many definitions, forms, political agendas and versions of reality represented by the term ‘documentary film’. Course Requirements The class meets once a week for three hours of lecture, discussion and screenings. Attendance is obligatory. A Cinematheque screening or some other event of relevance to the class may be scheduled, with due notice, with provisions made for those students who cannot attend them. There will be four graded assignments: a library-based research paper; a midterm; a film analysis paper; and a final exam. Each week there will be an obligatory short essay or research project, examining issues discussed in the textbook, in specific articles and in documentaries screened during that day. These weekly assignments will be part of your attendance and participation portion of the grade. They are due at the beginning of each class meeting, but collected the day of the midterm, 1 March 16, 2019 (weeks 2-8), and the last day of class, handed in with the Final Exam, May 14, 2019 (weeks 11-16). -

1 "Documentary Films" an Entry in the Encylcopedia of International Media

1 "Documentary Films" An entry in the Encylcopedia of International Media and Communication, published by the Academic Press, San Diego, California, 2003 2 DOCUMENTARY FILMS Jeremy Murray-Brown, Boston University, USA I. Introduction II. Origins of the documentary III. The silent film era IV. The sound film V. The arrival of television VI. Deregulation: the 1980s and 1990s VII. Conclusion: Art and Facts GLOSSARY Camcorders Portable electronic cameras capable of recording video images. Film loop A short length of film running continuously with the action repeated every few seconds. Kinetoscope Box-like machine in which moving images could be viewed by one person at a time through a view-finder. Music track A musical score added to a film and projected synchronously with it. In the first sound films, often lasting for the entire film; later blended more subtly with dialogue and sound effects. Nickelodeon The first movie houses specializing in regular film programs, with an admission charge of five cents. On camera A person filmed standing in front of the camera and often looking and speaking into it. Silent film Film not accompanied by spoken dialogue or sound effects. Music and sound effects could be added live in the theater at each performance of the film. Sound film Film for which sound is recorded synchronously with the picture or added later to give this effect and projected synchronously with the picture. Video Magnetized tape capable of holding electronic images which can be scanned electronically and viewed on a television monitor or projected onto a screen. Work print The first print of a film taken from its original negative used for editing and thus not fit for public screening. -

Britten Curriculum Upload

Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra Concept by Daniel Meyer Curriculum Designed by Steven Weiser and the Erie Philharmonic Education Committee Table of Contents 1. Pre-Tests • Grades K-2 all lessons combined • Lesson 1 (Grades 3+) • Lesson 2 (Grades 3+) • Lesson 3 (Grades 3+) 2. CD Track Listing and Listening Guide for Teachers 3. Map of the Orchestra 4. History of the Erie Philharmonic 5. Lesson 1 • Lesson Plan • Orchestra Map Exploration • Identifying Instruments 6. Lesson 2 • Lesson Plan • Sound Exploring • Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra 7. Game Break • Maze - Grades K-2, 3+ • Word Search - Grades K-2, 3+ • Coloring - all Grades 8. Brief History of the Warner Theatre 9. Lesson 3 • Musical Characteristics SPONSORED BY 10. What to Expect at the Concert 11. Post-Tests • Grades K-2 all lessons combined • Lesson 1 (Grades 3+) • Lesson 2 (Grades 3+) • Lesson 3 (Grades 3+) Pre-Test (Grades K-2) Name ______________________ 1. Can you name an instrument from the orchestra? 2. Can you name one of the families of the orchestra? 3. Can you name an instrument that has strings? 4. Can you name an instrument that is made of brass? Pre-Test Lesson 1 (Grades 3+) Name ______________________ 1. Can you list the 4 families of a symphony orchestra? 1. 2. 3. 4. 2. Can you name these instruments? ______________ ______________ _________________ 3. Is this instrument from the Brass or Woodwind family? _______________________________ 4. Is this instrument from the Percussion or String family? ____________________________ 5. What does a string player use to create a sound on their instrument? ____________________________________________________ 6. -

DRN 125 Pp10-19

DRN 125 Spring 2020 Text_Double Reed 75.qxd 30/01/2020 09:14 Page 8 Reeds That Don’t Leak Julian Roberts reveals his personal tips for some critical stages of the reed-making process. As far as I’m concerned making reeds The next critical moment is when you is a total waste of time. I aim to make as form the end of the reed. The aim here few as possible and find that they last is to form as round a tube as possible. several months if alternated with others. The cane must be in a very pliable and There are plenty of guides on how to malleable state. It should have been make reeds and probably lots of better soaked several hours prior to the ideas and methods than mine; however profiling, shaping and construction stage. I’ve managed to make a living playing Now when forming it into a tube, as well First Bassoon in various orchestras for as it being well saturated, I steam it by 42 years, making noises through my own sitting it on the lid of a saucepan full of reeds. Some students I know were having rapidly boiling water, right where the lid trouble with their reeds leaking, so I put has holes for the steam to escape. You this together for them and offer it here in may cut right through the cane as I do, case it’s also useful for you. So this is not or just score it. Whichever method, the a ‘how to make a reed’ article, it is a tube must be persuaded into as round a focus on a few interesting moments of the state as possible. -

Spring 2018 ENG 818.002 |Studies in Genre and Media Topic: “Substrates of Cinema: Infrastructure, Media, Logistics” Dr

Spring 2018 ENG 818.002 |Studies in Genre and Media Topic: “Substrates of Cinema: Infrastructure, Media, Logistics” Dr. Justus Nieland | [email protected] Tuesday, 4:10-7pm The Forgotten Space (2010), Allan Sekula and Noël Burch This seminar explores what anthropologist and media historian Brian Larkin calls the “poetics and politics of infrastructure” through a range of films, videos, and art practices, from the late nineteenth century to the present. Both omnipresent and unseen, infrastructure has a way of receding from view until it fails, often catastrophically. Think of the BP’s Deepwater Horizon spill, the Dakota Access Pipeline stand-off, or even closer to home, the ongoing Flint water crisis. Globally, contemporary debates about the Anthropocene have brought into geological visibility the vast infrastructural project of modernity, one whose disastrous ecological implications, one would think, can no longer be refuted. But we now live in the Trump Era, where anything can be denied, and in the early days of an administration that came to power on the promise of linking a restrictive nationalist vision to promises of infrastructural renewal. Infrastructure, for ever-more-urgent reasons, continues to structure and demand our attention, our energies, and our resources, in every sense. Infrastructure’s current return to visibility in political and civic life has produced a discernible infrastructural turn in arts and humanities scholarship over the last decade. “To be modern,” as historian of technology Paul Edwards once insisted, “is to live by means of infrastructures”— systems that link the various scales of time, space, and social organization, and thus form the socio-technical foundations of modernity itself. -

Press Release Ida Ekblad FINAL

Christen Sveaas Art Foundation: This is the Night Mail selected by Ida Ekblad 27 August 2021 – 2 January 2022 Gallery 7, Free Entry #ChristenSveaasArt An artist night train travels from Norway to Whitechapel Gallery this autumn. 5 August 2021 – The dreams, nightmares and twilight landscapes of 35 international artists are brought together in This is the Night Mail, an artist- curated display by Ida Ekblad (b. 1980, Norway). Drawing from the personal collections of Christen Sveaas and that of the Christen Sveaas Art Foundation, the exhibition creates a densely-packed mise-en-scène featuring painting, photography, sculpture and drawings. This is the Night Mail is the first line of W.H. Auden’s 1936 poem describing a train journey across a sleeping Britain as it carries the nation’s mail. It accompanied a documentary film commissioned by the General Post Office with a propulsive soundtrack by a young Benjamin Britten. The slumbering mystery of Auden’s verse inspired Ekblad’s selection of works in the Collection, which the artist arranges across three imagined train compartments. Ekblad is renowned for her polychromatic, gestural paintings that often expand into immersive environments. Coming from the land of both the longest and the shortest night, she shares a preoccupation with many artists featured in the exhibition, using the nocturne as subject. The exhibition explores how moonlit interiors, land and seascapes form the backdrop for scenes of dream or nightmare, drama and transgression. Ekblad’s selection includes late 19th and 20th century Norwegian artists whose shimmering and mysterious canvases will be new to British audiences. -

1 This Chronology Includes All of the Core Repertoire Appearing in Each

New Model Music Curriculum Appendix 2 – Chronology: Repertoire in Context This chronology includes all of the Core Repertoire appearing in each Key Stage and Year as well as additional repertoire appropriate to learning based on the Model Music Curriculum. It is presented in chronological order of the year in which the piece or song was written and grouped by era in order to help pupils develop their knowledge of different musical periods and styles. Traditional Folk and World music can be used to enhance and deliver aspects of the Model Music Curriculum. They are especially useful in developing aural awareness, and to help pupils appreciate and understand music from different traditions. Items in bold indicate Foundation Listening repertoire that appears within the Model Music Curriculum. The suggested curriculum year is given as a guideline for its use. Early Period Year Composer Title of Piece Curriculum Source Year 1000 Anon Orientis Partibus 8 Orientis partibus - YouTube Medieval mystery play 1130 Hildegard Hortus Deliciarum 7 Hildegard von Bingen - Hortus Deliciarum - YouTube 1140 Hildegard O Euchari 4 ABRSM Classical 100 1200 Anon Ductias 1 & 2 7 Ductia #1 from the 13th century for two voices - YouTube Ductia #2 from the 13th century for two voices - YouTube 1225 Anon Miri it is while 7 Mediaeval English Folk Song - Miri It Is While Sumer Ilast sumer ilast - YouTube 1250 Anon Sumer is Icumen In 7 Sumer is Icumen in (The Hilliard Ensemble) - YouTube Renaissance Period Year Composer Title of Piece Curriculum Source Year 1551 Susato -

Information to Users

Benjamin Britten's "The Company of Heaven". Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Weber, Michael James. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 04:21:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/185097 INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thy-,;" tIme thesis and dissertation .copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

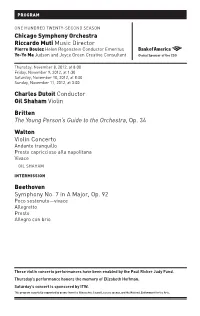

Charles Dutoit Conductor Gil Shaham Violin Britten the Young Person's

Program ONe huNdred TweNTy-SeCONd SeASON Chicago Symphony orchestra riccardo muti music director Pierre Boulez helen regenstein Conductor emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, November 8, 2012, at 8:00 Friday, November 9, 2012, at 1:30 Saturday, November 10, 2012, at 8:00 Sunday, November 11, 2012, at 3:00 Charles Dutoit Conductor gil Shaham Violin Britten The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, Op. 34 Walton Violin Concerto Andante tranquillo Presto capriccioso alla napolitana Vivace Gil ShAhAm IntermISSIon Beethoven Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92 Poco sostenuto—vivace Allegretto Presto Allegro con brio These violin concerto performances have been enabled by the Paul Ricker Judy Fund. Thursday’s performance honors the memory of Elizabeth Hoffman. Saturday’s concert is sponsored by ITW. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. CommentsCommentS by PhilliDanielP J hAFFuscheré PhilliP huSCher Benjamin Britten Born November 22, 1913, Lowestoft, England. Died December 4, 1976, Aldeburgh, England. The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra: Variations and Fugue on a theme of Henry Purcell, op. 34 y the time he composed The late in 1944 to compose a score BYoung Person’s Guide to the for an educational film: involving Orchestra in 1946, Benjamin Britten the popular English conductor was the internationally renowned Malcolm Sargent and the London composer of the opera Peter Grimes. Symphony Orchestra, this was Yet the commission to compose this to introduce schoolchildren to now popular concert-hall work did the instruments of a symphony not follow the phenomenal success orchestra, to be distributed by the of that landmark opera, but had in Ministry of Education. -

Benjamin Britten At

13/26 Benjamin Britten at 100 BFI Southbank celebrates the centenary of one of Britain’s most innovative composers, with Peter Morley OBE, Dame Josephine Barstow, Tony Palmer, Phyllida Lloyd, John Bridcut and Paul Kildea all appearing onstage 2013 marks the centenary of the birth of Benjamin Britten, one of Britain’s greatest composers. Beginning in September and running into the first week of October, BFI Southbank will be holding a season to celebrate the ways in which Britten contributed to cinema and television, either through writing film scores or adapting operas, or as the subject of remarkable documentaries about his life and work. Benjamin Britten at 100 will include screenings of documentaries from the GPO Film Unit (for which Britten composed the music), plus a re- mastered screening of The Turn of the Screw (1959) introduced by director Peter Morley OBE. Further highlights will include special previews of new films by Tony Palmer and John Bridcut (Nocturne and Britten’s Endgame respectively) followed by director Q&As and a Season Introduction by Britten biographer Paul Kildea (which will include rarely screened home movie footage which has been digitised by the BFI National Archive). This season will give audiences a unique opportunity to augment their understanding of this remarkable composer, whose career was so inextricably linked to film and television. In 1935 aged only 21, Benjamin Britten was plucked from relative obscurity by (depending on which version of events you read) either John Grierson or Alberto Cavalcanti. Grierson was at that time the head of the GPO Film Unit, with Cavalcanti as his assistant, and required a young and talented composer to write scores for him. -

Benjamin Britten and Comtemporary Art Song Literature

Benjamin Britten and Contemporary Art Song Literature: A Discussion of A Birthday Hansel Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Collett, Jacqueline L. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 11/10/2021 08:43:21 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/626233 BENJAMIN BRITTEN AND COMTEMPORARY ART SONG LITERATURE: A DISCUSSION OF A BIRTHDAY HANSEL by Jacqueline L. Collett A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In The Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1986 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA SCHOOL OF MUSIC I hereby recommend that this document prepared under my direction by Jacqueline L. Collett entitled Benjamin Britten and Contemporary Art Song Literature: A Discussion of A Birthday Hansel be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. (/,,,,, 4,a//6 Signature cif Major Professor Acceptance for the School of Music: ctor, Graduate Studies in Music TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS iv CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION AND BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH 1 2. BRITTEN'S CONTRIBUTION TO CONTEMPORARY ART SONG 10 3. A DISCUSSION OF A BIRTHDAY HANSEL 15 4. CONCLUSION 23 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 24 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figures Page 1. Britten: "Birthday Song ", measures 1 -6 18 2.