London's Lost Rivers: the Hackney Brook and Other North West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Igniting Change and Building on the Spirit of Dalston As One of the Most Fashionable Postcodes in London. Stunning New A1, A3

Stunning new A1, A3 & A4 units to let 625sq.ft. - 8,000sq.ft. Igniting change and building on the spirit of Dalston as one of the most fashionable postcodes in london. Dalston is transforming and igniting change Widely regarded as one of the most fashionable postcodes in Britain, Dalston is an area identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London. It is located directly north of Shoreditch and Haggerston, with Hackney Central North located approximately 1 mile to the east. The area has benefited over recent years from the arrival a young and affluent residential population, which joins an already diverse local catchment. , 15Sq.ft of A1, A3000+ & A4 commercial units Located in the heart of Dalston and along the prime retail pitch of Kingsland High Street is this exciting mixed use development, comprising over 15,000 sq ft of C O retail and leisure space at ground floor level across two sites. N N E C T There are excellent public transport links with Dalston Kingsland and Dalston Junction Overground stations in close F A proximity together with numerous bus routes. S H O I N A B L E Dalston has benefitted from considerable investment Stoke Newington in recent years. Additional Brighton regeneration projects taking Road Hackney Downs place in the immediate Highbury vicinity include the newly Dalston Hackney Central Stoke Newington Road Newington Stoke completed Dalston Square Belgrade 2 residential scheme (Barratt Road Haggerston London fields Homes) which comprises over 550 new homes, a new Barrett’s Grove 8 Regents Canal community Library and W O R Hoxton 3 9 10 commercial and retail units. -

HACKNEY SOCIAL RADIO – the Story So Far June 2020 – April 2021

HACKNEY SOCIAL RADIO – The Story So Far June 2020 – April 2021 SUMMARY OF ACHIEVEMENTS During the height of the first COVID-19 lockdown, from June to September 2020, we successfully produced 15 episodes for the first series of Hackney Social Radio – a community radio show created by older people, for older people, specifically aimed at the digitally isolated in the London Borough of Hackney. As the country went into the second lockdown, we re-launched for Series 2 with the intention of supporting our community of makers and listeners for as long as we could. We were fortunate to receive funding from the Henry Smith charity and CAF and will have created 35 episodes for our second series, which ends on 14th July 2021. To date we have produced 41 weekly 59-minute radio show, which broadcast every Wednesday at 11am. Programmes are transmitted through Resonance 104.4FM, played out on their online radio player, and available for ongoing playback through Mixcloud. We enabled 178 local people to participate in the production of the show in the first series and so far, 181 people in the second series – these included the production team, feature makers, feature contributors, editors, and interviewees – local artists and creatives, community activists, volunteers, service users and experts such as representatives from Local Government, GPs, faith leaders, advisors, and community champions. Our contributors have represented the diverse communities of Hackney with features and interviews covering for example Windrush events, Chinese New Year, Jewish and Muslim Festivals. We have covered a wide range of art forms from theatre to photography and music with our 78-year-old DJ playing requests from our listeners. -

Hackney Archives - History Articles in Hackney Today by Subject

Hackney Archives - History Articles in Hackney Today by Subject These articles are published every fortnight in Hackney Today newspaper. They are usually on p.25. They can be downloaded from the Hackney Council website at http://www.hackney.gov.uk/w-hackneytoday.htm. Articles prior to no.158 are not available online. Issue Publication Subject Topic no. date 207 11.05.09 125-130 Shoreditch High Street Architecture: Business 303 25.03.13 4% Industrial Dwellings Company Social Care: Jewish Housing 357 22.06.15 50 years of Hackney Archives Research 183 12.05.08 85 Broadway in Postcards Research Methods 146 06.11.06 Abney Park Cemetery Open Spaces 312 12.08.13 Abney Park Cemetery Registers Local History: Records 236 19.07.10 Abney Park chapel Architecture: Ecclesiastical 349 23.02.15 Activating the Archive Local Activism: Publications 212 20.07.09 Air Flight in Hackney Leisure: Air 158 07.05.07 Alfred Braddock, Photographer Business: Photography 347 26.01.15 Allen's Estate, Bethune Road Architecture: Domestic 288 13.08.12 Amateur sport in Hackney Leisure: Sport 227 08.03.10 Anna Letitia Barbauld, 1743-1825 Literature: Poet 216 21.09.09 Anna Sewell, 1820-1878 Literature: Novelist 294 05.11.12 Anti-Racism March Anti-Racism 366 02.11.15 Anti-University of East London Radicalism: 1960s 265 03.10.11 Asylum for Deaf and Dumb Females, 1851 Social Care 252 21.03.11 Ayah's Home: 1857-1940s Social Care: Immigrants 208 25.05.09 Barber's Barn 1: John Okey, 1650s Commonwealth and Restoration 209 08.06.09 Barber's Barn 2: 16th to early 19th Century Architecture: -

London Fields Studios 139-141 Mare Street London E8

London Fields Studios FIELDS LONDON 139-141 Mare Street London E8 3RH STUDIOS Location FIELDS LONDON London Fields Studios is located in the This pocket of Hackney has long heart of East London’s trendy London been home to a large community of Fields district, on the corner of Mare media companies, designers, artists Street and Warburton Road. and fashionistas. In recent years, Fashionable Broadway Market is popular popularity in the area has increased amongst those seeking food, drink, which has resulted in numerous mixed clothing and crafts from its array of use developments and an influx of independent cafés, bars, restaurants, newcomers. STUDIOS shops and weekend street market. Local occupiers and amenities include; Between London Fields Studios and WeWork, Netil House, Netil Market, Sugru, Broadway Market lies London Fields which London Fields Brewery, The Martello provides a popular open space and Hall pub, Wringer and Mangle Bar & heated Lido for all to enjoy, BBQ’s and Restaurant, Franco Manca, Cat & Mutton cricket can also be appreciated in the and The Corner coffee shop. summer months. Central London is easily accessible with Liverpool Street station providing the gateway. Liverpool Street station can be accessed within less than 15 minutes from London Fields Studios via London Fields station. London Fields FIELDS LONDON ST HIGH HACKNEY DOWNS HOMER TON 0.2 miles – 4 minutes DALSTON KINGSLAND London Overground HACKNEY CENTRAL HOMERTON BAL LS POND R D DALSTON LANE Cambridge Heath DALSTON JUNCTION G 0.5 miles – 10 minutes A SC -

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD ACC/2423 Reference Description Dates LEE CONSERVANCY BOARD ENGINEER'S OFFICE Engineers' reports and letter books LEE CONSERVANCY BOARD: ENGINEER'S REPORTS ACC/2423/001 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1881 Jan-1883 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/002 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1884 Jan-1886 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/003 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1887 Jan-1889 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/004 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1890 Jan-1893 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/005 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1894 Jan-1896 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/006 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1897 Jan-1899 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/007 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1903 Jan-1903 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/008 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1904 Jan-1904 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/009 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1905 Jan-1905 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/010 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1906 Jan-1906 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD ACC/2423 Reference Description Dates ACC/2423/011 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1908 Jan-1908 Lea navigation/ stort navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/012 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1912 Jan-1912 Lea navigation/ stort navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/013 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1913 Jan-1913 Lea navigation/ stort navigation -

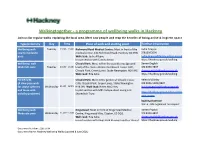

Hackney Wellbeing Walks

Walkingtogether - a programme of wellbeing walks in Hackney Join us for regular walks exploring the local area. Meet new people and reap the benefits of being active & in green space Type/intensity Day Time Place of walk and starting point Further information Wellbeing walk Tuesday 13.00 - 13.40 Richmond Road Medical Centre: Meet in front of the Sadie Alleyne Low to moderate medical centre, 136 Richmond Road, Hackney E8 3HN. 07815993599 pace Walk lead: Sadie Alleyne [email protected] In partnership with Family Action https://hackney.gov.uk/walking Wellbeing walk Clissold Park: Meet within the outside area (ground Darren English Moderate pace Tuesday 13.00 - 14.00 level) of the main entrance to Clissold House Café, 020 8356 4897 Clissold Park, Green Lanes, Stoke Newington, N16 9HJ. [email protected] Walk lead: Rita Saha https://hackney.gov.uk/walking Fit 4 Health Clissold Park: Meet in the garden of Clissold House Helen McGinley (A slow pace walk Cafe, Clissold Park, Green Lanes, Stoke Newington, 020 8356 5285/4897 for stroke sufferers Wednesday 11.30 - 12.15 N16 9HJ. Walk lead: Helen McGinley [email protected] and those with In partnership with MRS Independent Living and https://hackney.gov.uk/after-stroke- mobility problems) Shoreditch Trust. programme Booking essential Dial -a -ride organised on request Wellbeing walk Kingsmead: Meet in front of Kingsmead Medical Darren English Moderate pace Wednesday 11.00 – 12.00 Centre, Kingsmead Way, Clapton, E9 5QG. 020 8356 4897 Walk lead: Rita Saha. [email protected] -

101 DALSTON LANE a Boutique of Nine Newly Built Apartments HACKNEY, E8 101 DLSTN

101 DALSTON LANE A boutique of nine newly built apartments HACKNEY, E8 101 DLSTN 101 DLSTN is a boutique collection of just 9 newly built apartments, perfectly located within the heart of London’s trendy East End. The spaces have been designed to create a selection of well- appointed homes with high quality finishes and functional living in mind. Located on the corner of Cecilia Road & Dalston Lane the apartments are extremely well connected, allowing you to discover the best that East London has to offer. This purpose built development boasts a collection of 1, 2 and 3 bed apartments all benefitting from their own private outside space. Each apartment has been meticulously planned with no detail spared, benefitting from clean contemporary aesthetics in a handsome brick external. The development is perfectly located for a work/life balance with great transport links and an endless choice of fantastic restaurants, bars, shops and green spaces to visit on your weekends. Located just a short walk from Dalston Junction, Dalston Kingsland & Hackney Downs stations there are also fantastic bus and cycle routes to reach Shoreditch and further afield. The beautiful green spaces of London Fields and Hackney Downs are all within walking distance from the development as well as weekend attractions such as Broadway Market, Columbia Road Market and Victoria Park. • 10 year building warranty • 250 year leases • Registered with Help to Buy • Boutique development • Private outside space • Underfloor heating APARTMENT SPECIFICATIONS KITCHEN COMMON AREAS -

The Navigation of the River Lee (1190 – 1790)

Edmonton Hundred Historical Society Occasional Paper New Series No. 36 by J.G.L.Burnby and M.Parker. Published 1978 Added to the site by kind permission of Mr Michael Parker THE NAVIGATION OF THE RIVER LEE (1190 – 1790) PREFACE As the men of the river frequently pointed out the Lee is one of the "great rivers of the realm", and it is only fitting that its history should be traced; indeed it is surprising that the task has not been carried out far earlier than this. Regretfully the story of its busiest period in the days of post-canalisation has had to be left to another, later Occasional Paper. The spelling of the name of the river has varied over the centuries. In 1190 it was referred to as "the water of Lin", in the fourteenth century as "La Leye", the cartographer Saxton seems to have been the first to introduce "Lea" to map-makers in 1576, in the eighteenth century it was not infrequently called the "Ware River" but the commonest spelling would seem to be "Lee" and it is to this which we have decided to adhere. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We would like to thank the London Borough of Haringey Libraries panel for their financial assistance in the publication of this paper. Our gratitude also goes to the Marquess of Salisbury for granting permission to reproduce the maps held in the Hatfield House Collection. A number of people have most generously helped us in the production of this paper. Mrs.H.Baker has with her usual expertise drawn the map of the lower reaches of the river, and Mr.Neil Clements is responsible for the charming reproductions of the prints of the Powder Mill at Waltham Abbey and the river at Ware. -

FREE of TIE LEASE for SALE Hackney / London Fields, E8

agg.uk.com | 020 7836 7826 FREE OF TIE LEASE FOR SALE Hackney / London Fields , E 8 PRINCE ARTHUR, 95 FOREST ROAD, HACKNEY, LONDON, E8 3BH • Attractive pub on the corner of Forest Road and Elrington Road in Hackney • Situated within close proximity of London Fields and Dalston • Successful business with proven accounts showing turnover of circa £610,000 • 20 year free of tie lease for the ground floor and basement expiring November 2037 • Passing rent £50,000 per annum • Well-presented trading area within popular residential locality LEASE FOR SALE – free of all ties OFFERS IN EXCESS OF £150,000 SUBJECT TO CONTRACT – sole selling agents LONL390 8 Exchange Court, Covent Garden, London WC2R 0JU • Tel: 020 7836 7826 • www.agg.uk.com A.R. Alder BSc (Hons) FRICS • J.B. Grimes BSc(Hons) MRICS • D. Gooderham MRICS R.A. Negus BSc MRICS • M. L. Penfold BSc(Hons) MRICS Notice AG&G for themselves and for the vendor of this property, whose agents they are given notice that 1. These particulars do not form any part of the offer or contract. 2 They are intended to give a fair description of the property. but neither AG&G nor the vendor accept responsibility for any error they may contain, however caused. Any intending purchaser must therefore satisfy himself by inspection or otherwise as to their correctness. 3 neither AG&G, nor any of their employees, has any authority to make or give any further representation or warranty in relation to this property. Unless otherwise stated, all prices and rents are quoted exclusive of Value Added Tax (VAT). -

Regent's Canal Conservation Area Appraisal

1 REGENT’S CANAL CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Urban Design and Conservation Team Regeneration & Planning Division London Borough of Hackney 263 Mare Street London E8 1HT October 2007 Regent’s Canal Conservation Area Appraisal October 2007 2 All images are copyright of Hackney Archives/LB Hackney, unless otherwise stated London Borough Hackney, LA08638X (2006). Regent’s Canal Conservation Area Appraisal October 2007 3 CONTENTS 1 Introduction 1.1 What is a Conservation Area? 1.2 Location and Context of the Conservation Area 1.3 The format of the Conservation Area Appraisal 1.4 Acknowledgments 1.5 Conservation Area Advisory Committees 2 Planning Context 2.1 National Policy 2.2 Local Policies 3 Historic Development of the Area 3.1 Archaeological Significance 3.2 Origins and Historic development 3.3 Geology and Topography 4 The Conservation Area and its Surroundings 4.1 The Surroundings and Setting of the Conservation Area 4.2 General Description of the Conservation Area 4.3 Plan Form and Streetscape 4.4 Views, Focal Points and Focal Buildings 4.5 Landscape and Trees 4.6 Activities and Uses 5 The Buildings of the Conservation Area 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Listed buildings 5.3 Buildings of Local Significance 5.4 Buildings of Townscape Merit 6 “SWOT” Analysis 6.1 Strengths 6.2 Weaknesses 6.3 Opportunities 6.4 Threats 7 Conclusion Map of Regent’s Canal Conservation Area Regent’s Canal Conservation Area Appraisal October 2007 4 APPENDICES Appendix A Historic Maps of the Regent’s Canal Conservation Area Appendix B Schedule of Listed and Locally Listed Buildings and Buildings of Townscape Merit Appendix C Bibliography Appendix D List of illustrations Appendix E Further information Regent’s Canal Conservation Area Appraisal October 2007 5 1 INTRODUCTION The Regent’s Canal Conservation Area was designated by the London Borough of Hackney in 2007. -

Geology and London's Victorian Cemeteries

Geology and London’s Victorian Cemeteries Dr. David Cook Aldersbrook Geological Society 1 Contents Part 1: Introduction Page 3 Part 2: Victorian Cemeteries Page 5 Part 3: The Rocks Page 7 A quick guide to the geology of the stones used in cemeteries Part 4: The Cemeteries Page 12 Abney Park Brompton City of London East Finchley Hampstead Highgate Islington and St. Pancras Kensal Green Nunhead Tower Hamlets West Norwood Part 5: Appendix – Page 29 Notes on other cemeteries (Ladywell and Brockley, Plumstead and Charlton) Further Information (websites, publications, friends groups) Postscript 2 Geology and London’s Victorian Cemeteries Part 1: Introduction London is a huge modern city - with congested roads, crowded shopping areas and bleak industrial estates. However, it is also a city well-served by open spaces. There are numerous small parks which provide relief retreat from city life, while areas such as Richmond Park and Riverside, Hyde Park, Hampstead Heath, Epping Forest and Wimbledon Common are real recreational treasures. Although not so obviously popular, many of our cemeteries and churchyards provide a much overlooked such amenity. Many of those established in Victorian times were designed to be used as places of recreation by the public as well as places of burial. Many are still in use and remain beautiful and interesting places for quiet walks. Some, on ceasing active use for burials, have been developed as wildlife sanctuaries and community parks. As is the case with parklands, there are some especially splendid cemeteries in the capital which stand out from the rest. I would personally recommend the City of London, Islington and St. -

Hackney Biodiversity Action Plan 2012-17

Image © Rob Sambrooks Image © Rob Hackney Biodiversity Action Plan 2012-17 black 11 mm clearance all sides white 11 mm clearance PJ46645 all sides CMYK 11 mm clearance all sides Councillor Introduction Cllr Jonathan McShane, Cabinet Member for Health and Community Services Cllr Sophie Linden, Cabinet Member for Crime, Sustainability and Customer Services It gives us great pleasure to introduce the first Hackney Biodiversity Action Plan. This document sets out the guiding principles of how Hackney Council and our partners will work to protect and enhance the wildlife and natural environment of the Borough. The Action Plan has been developed by the Council in collaboration with the Hackney Biodiversity Partnership. Hackney’s open spaces and structures provide homes for a range of common and rare wildlife, including birds, bats and plants. The Biodiversity Action Plan is about more than protecting our wildlife. Biodiversity contributes to our health and wellbeing, provides places for us to enjoy and helps us to adapt to the threat of climate change. This Biodiversity Action Plan identifies the key issues for biodiversity and clearly sets out how we will work to improve our open spaces and built environment. Working in partnership we will raise awareness of the value of our biodiversity, ensure that our green and open spaces are resources that all of our residents can enjoy and promote the wider benefits that biodiversity can provide. Hackney’s environment helps to define the Borough. It is important that we continue to strive to protect and improve our biodiversity, responding to the needs and aspirations of Hackney and its residents in the years to come.