Regent's Canal Conservation Area Appraisal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Igniting Change and Building on the Spirit of Dalston As One of the Most Fashionable Postcodes in London. Stunning New A1, A3

Stunning new A1, A3 & A4 units to let 625sq.ft. - 8,000sq.ft. Igniting change and building on the spirit of Dalston as one of the most fashionable postcodes in london. Dalston is transforming and igniting change Widely regarded as one of the most fashionable postcodes in Britain, Dalston is an area identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London. It is located directly north of Shoreditch and Haggerston, with Hackney Central North located approximately 1 mile to the east. The area has benefited over recent years from the arrival a young and affluent residential population, which joins an already diverse local catchment. , 15Sq.ft of A1, A3000+ & A4 commercial units Located in the heart of Dalston and along the prime retail pitch of Kingsland High Street is this exciting mixed use development, comprising over 15,000 sq ft of C O retail and leisure space at ground floor level across two sites. N N E C T There are excellent public transport links with Dalston Kingsland and Dalston Junction Overground stations in close F A proximity together with numerous bus routes. S H O I N A B L E Dalston has benefitted from considerable investment Stoke Newington in recent years. Additional Brighton regeneration projects taking Road Hackney Downs place in the immediate Highbury vicinity include the newly Dalston Hackney Central Stoke Newington Road Newington Stoke completed Dalston Square Belgrade 2 residential scheme (Barratt Road Haggerston London fields Homes) which comprises over 550 new homes, a new Barrett’s Grove 8 Regents Canal community Library and W O R Hoxton 3 9 10 commercial and retail units. -

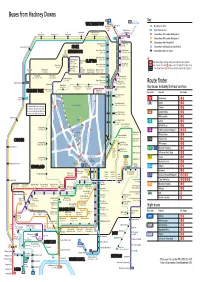

Buses from Hackney Downs

Buses from Hackney Downs 48 N38 N55 continues to Key WALTHAMSTOW Woodford Wells Walthamstow Hoe Street 30 Day buses in black Central Whipp’s Cross N38 Night buses in blue Stamford Hill Clapton Common Roundabout Manor House Amhurst Park Stamford Hill Broadway Portland Avenue r- Connections with London Underground 56 55 Leyton o Connections with London Overground Baker’s Arms Clapton Common Lea Bridge Road n Connections with National Rail Forburg Road Argall Way Seven Sisters Road STOKE d Connections with Docklands Light Railway Upper Clapton Road Lea Bridge Road f Connections with river boats Stoke NEWINGTON Jessam Avenue Lee Valley Riding Centre Newington Upper Clapton Road Lea Bridge Road Stoke Newington Cazenove Road Lee Valley Ice Centre Ú High Street Northwold CLAPTON Red discs show the bus stop you need for your chosen Garnham Street Road Lea Bridge Road Manor Road Upper Clapton Road r Stoke Newington Rossington Street Chatsworth Road bus service. The disc appears on the top of the bus stop Listria Park Stoke 1 2 3 High Street 4 5 6 in the street (see map of town centre in centre of diagram). Blackstock Manor Road Brooke Road Newington Northwold Road Northwold Road Road Lordship Road Common Geldstone Road Clapton Library Lordship Park Manor Road 276 Clapton Lea Bridge Road Queen Elizabeth Walk Heathland Road Stoke Newington Wattisfield Road Police Station Upper Clapton Road Brooke Road Lea Bridge Road Finsbury Park 106 Upper Clapton Road Route finder Manse Road Downs Road Rectory Road Rendlesham Road Kenninghall Road Lea Bridge Roundabout Day buses including 24-hour services Rectory Road Ottaway Street Muir Road 38 Downs Road Downs Road FINSBURY PARK Clapton Pond Bus route Towards Bus stops Lower Clapton Road E QU N Clapton Pond E Holloway A AMHUR EN ST AD 254 L Marble Arch T S Nag’s Head ERRACE O 30 L D R L O c p E W D N Lower Clapton Road Leyton 38 Z R EW EL O Hackney Downs I Millfields Road (488 only) L A The yellow tinted area includes every ` F K AM D C n T Victoria E bus stop up to about one-and-a-half A K H HU miles from Hackney Downs. -

Shacklewell Green Conservation Area Appraisal

1 SHACKLEWELL GREEN CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL October 2017 2 This Appraisal has been prepared by Matt Payne, Senior Conservation & Design Officer (contact: [email protected]), for the London Borough of Hackney (LBH). The document was written in 2017, which is the 50 th anniversary of the introduction of Conservation Areas in the Civic Amenities Act 1967. All images are copyright of Hackney Archives or LBH, unless otherwise stated Maps produced under licence: London Borough of Hackney. Shacklewell Green Conservation Area Appraisal October 2017 3 CONTENTS 1 Introduction 1.1 Statement of Significance 1.2 What is a Conservation Area? 1.3 The format of the Conservation Area Appraisal 1.4 The benefits of Conservation Area Appraisal 1.5 Acknowledgments 2 Planning Context 2.1 National Policies 2.2 Local Policies 3 Assessment of Special Interest Location and Setting 3.1 Location and Context 3.2 The Surrounding Area and Setting 3.3 Plan Form and Streetscape 3.4 Geology and Topography Historic Development 3.5 Archaeological Significance 3.6 Origins, Historic Development and Mapping Architectural Quality and Built Form 3.7 The Buildings of the Conservation Area Positive Contributors 3.8 Listed Buildings 3.9 Locally Listed Buildings 3.10 Buildings of Townscape Merit Neutral & Negative Contributors 3.11 Neutral Contributors 3.12 Negative Contributors Open Space, Parks and Gardens, and Trees 3.13 Landscape and Trees 3.14 Views and Focal Points Activities and Uses 3.15 Activities and Uses 4 Identifying the Boundary 3.16 Map of the Proposed -

2,398 Sq Ft (223 M ) Arch 329 Stean Street Haggerston London E8

Arch 329 Stean Street Haggerston London E8 4ED . TO LET - Arch with a secure yard 2,398 sq ft (223 m2) B1 /B2/B8 Opportunity *or alternative uses STPP* Location Terms The subject property is located in prominent position to the A new full repairing and insuring lease is available for a term north east of the city and can be accessed from Stean Street and by agreement, at a rent of £60,000 per annum, plus VAT. Acton Mews. The A10 is a short distance to the west of the Subject to Contract. property and provides a direct route to the M25. The area is well served by public transport with a number of bus routes Description passing close to the premises, most notably from the A10 The property comprises of an unlined arch which can be Kingsland Road. Haggerston station (London Overground) is accessed from Stean Street or Acton Mews. The access on each located within 4 minutes walk of the property and provides elevation is via a manual sliding shutter door with a width of direct access into the city. 4.5m and height of 3.42m. Internally, the arch is in a Floor Areas (approx) GIA reasonable condition and benefits from:- Floor Areas GIA (approx): 2 Arch 329 Sq ft (m ) Strip Lighting Arch 2,398 223 3 Phase electricity Yard 1,059 98 Male/Female WC’s Total 3,457 321 Alarm System & CCTV 2 Gas fired blow heaters (unconnected) Legal Costs Rates We understand from the London Borough of Hackney that the Parking available on either side of the arch. -

Hackney Archives - History Articles in Hackney Today by Subject

Hackney Archives - History Articles in Hackney Today by Subject These articles are published every fortnight in Hackney Today newspaper. They are usually on p.25. They can be downloaded from the Hackney Council website at http://www.hackney.gov.uk/w-hackneytoday.htm. Articles prior to no.158 are not available online. Issue Publication Subject Topic no. date 207 11.05.09 125-130 Shoreditch High Street Architecture: Business 303 25.03.13 4% Industrial Dwellings Company Social Care: Jewish Housing 357 22.06.15 50 years of Hackney Archives Research 183 12.05.08 85 Broadway in Postcards Research Methods 146 06.11.06 Abney Park Cemetery Open Spaces 312 12.08.13 Abney Park Cemetery Registers Local History: Records 236 19.07.10 Abney Park chapel Architecture: Ecclesiastical 349 23.02.15 Activating the Archive Local Activism: Publications 212 20.07.09 Air Flight in Hackney Leisure: Air 158 07.05.07 Alfred Braddock, Photographer Business: Photography 347 26.01.15 Allen's Estate, Bethune Road Architecture: Domestic 288 13.08.12 Amateur sport in Hackney Leisure: Sport 227 08.03.10 Anna Letitia Barbauld, 1743-1825 Literature: Poet 216 21.09.09 Anna Sewell, 1820-1878 Literature: Novelist 294 05.11.12 Anti-Racism March Anti-Racism 366 02.11.15 Anti-University of East London Radicalism: 1960s 265 03.10.11 Asylum for Deaf and Dumb Females, 1851 Social Care 252 21.03.11 Ayah's Home: 1857-1940s Social Care: Immigrants 208 25.05.09 Barber's Barn 1: John Okey, 1650s Commonwealth and Restoration 209 08.06.09 Barber's Barn 2: 16th to early 19th Century Architecture: -

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD ACC/2423 Reference Description Dates LEE CONSERVANCY BOARD ENGINEER'S OFFICE Engineers' reports and letter books LEE CONSERVANCY BOARD: ENGINEER'S REPORTS ACC/2423/001 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1881 Jan-1883 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/002 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1884 Jan-1886 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/003 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1887 Jan-1889 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/004 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1890 Jan-1893 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/005 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1894 Jan-1896 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/006 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1897 Jan-1899 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/007 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1903 Jan-1903 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/008 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1904 Jan-1904 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/009 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1905 Jan-1905 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/010 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1906 Jan-1906 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD ACC/2423 Reference Description Dates ACC/2423/011 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1908 Jan-1908 Lea navigation/ stort navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/012 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1912 Jan-1912 Lea navigation/ stort navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/013 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1913 Jan-1913 Lea navigation/ stort navigation -

Hackney to Bloomsbury: Mapping the London Left

Hackney to Bloomsbury: Mapping the London Left BORIS LIMITED WAREHOUSE ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS ESSEX UNITARIAN CHURCH THE ECONOMIST FABIAN SOCIETY Chapter 1: The Other Boris. The People of the Community of Hackney wish to propose vast amendments to the appeal for redevelopment of the Boris Limited Warehouse standing at 87-95 Hertford Road, N1 5AG. What is slated by the developer, Serdnol Properties SA, is quoted as “1,858 square meters of commercial space and nine new build terraced houses”, offering a sea of sameness to the area. Hackney is often described as an up-and-coming neighborhood. Rather, it is in a constant state of flux, and the building in question deserves to be a practical part of its current transition. As the facade stands, a boarded up boundary, somewhat dilapidated with rotting wood and rusted sign, one could imagine a city of squatters, as in the old New York tenements or East London slums, or more historically accurate, the tenants of the adjacent workhouse or personnel of this warehouse. This building has watched with its countenance the transformation of Hackney and the story of the politics of labour through central London which laid the foundation for its construction as an integral part not only of London’s history but of the lineage of western socialism. Boris Limited is not an icon, no great architect conceived its structure, no famous author resided there, and no great political movement hatched from an embryo within its walls. But what it stands for, the historic web which emanates from it and what its face has subsequently witnessed is the narrative of the development of socialism and modernity in the post-Eurocentric city. -

Rights to Light Consultation

Law Commission Consultation Paper No 210 RIGHTS TO LIGHT A Consultation Paper ii THE LAW COMMISSION – HOW WE CONSULT About the Law Commission: The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Law Commissioners are: The Rt Hon Lord Justice Lloyd Jones, Chairman, Professor Elizabeth Cooke, David Hertzell, Professor David Ormerod and Frances Patterson QC. The Chief Executive is Elaine Lorimer. Topic of this consultation: This Consultation Paper examines the law as it relates to rights to light. Rights to light are a type of easement which entitle a benefited owner to receive light to his or her windows over a neighbour’s land. We discuss the current law and set out a number of provisional proposals and questions on which we would appreciate consultees’ views. Geographical scope: This Consultation Paper applies to the law of England and Wales. Impact assessment: In Chapter 1 of this Consultation Paper we ask consultees to provide evidence in respect of a number of issues relating to rights to light, such as the costs of engaging in rights to light disputes. Any evidence that we receive will assist us in the production of an impact assessment and will inform our final recommendations for reform. Availability of materials: The consultation paper is available on our website at http://lawcommission.justice.gov.uk/consultations/rights-to-light.htm. Duration of the consultation: We invite responses from 18 February 2013 to 16 May 2013. Comments may be sent: By email to [email protected] OR By post to Nicholas Macklam, Law Commission, Steel House, 11 Tothill Street, London SW1H 9LJ Tel: 020 3334 0200 / Fax: 020 3334 0201 If you send your comments by post, it would be helpful if, whenever possible, you could also send them electronically (for example, on CD or by email to the above address, in any commonly used format). -

London Assembly Investigation Into Waterway Moorings

c/- Ridgeways Wharf, Brent Way, Brentford, TW8 8ES Chairman: Nigel Moore Matt Bailey Project Officer London Assembly City Hall The Queen’s Walk London, SE1 2AA Re: LONDON ASSEMBLY INVESTIGATION INTO WATERWAY MOORINGS WHO WE ARE 1. The Brentford Waterside Forum has been in operation for over 25 years, involving itself in all matters of waterside importance in the area, conducting dialogue with both developers and Hounslow Council. 2. Organisations represented on the Forum include: The Butts Society; Inland Waterways Association; The Hollows Association; MSO Marine; Brentford Dock Residents Association; Brentford Community Council; Brentford Marine Services; Holland Gardens Residents Community; Weydock Ltd; Thames & Waterways Stakeholders Forum; Sailing Barge Research; The Island Residents Group; Ferry Quays Residents Association 3. The Forum's Core Values and Objectives are stated as follows: "The rediscovery of the Waterside in Brentford is putting intense pressure on the water front. There is growing competition for access to the river and canal sides; pressure is mounting to create new economic activities and provide residential development on the waters edge. These pressures jeopardise both existing businesses and the right of Brentford people to access the water, which is part of their heritage. Access to the waterside in Brentford is made possible by the changing economic and commercial use of the water. 4. The role of the Waterside Forum is: to provide informed comment on proposed developments or changes. Brentford Waterside Forum will work with and through agencies to achieve the following: — A strategic context for waterside decision making. — To protect access to the waterside, its infrastructure and the water itself for people to use for recreation, enjoyment and business, emphasising business that need a waterside location to be successful. -

Consultation on Traffic Calming Scheme at City Road Lock, Regent’S Canal Feedback Results March 2012 Contents

Consultation on Traffic Calming Scheme at City Road Lock, Regent’s Canal Feedback Results March 2012 Contents Introduction Question 1. How often do you use the Regent’s Canal? Question 2. When you do use the Regent’s Canal do you mostly... Question 3. How far from the Regent’s Canal do you live? Question 4. Which London borough do you live in? Question 5. Do you perceive the speed of cyclists to be an issue on the Regent’s Canal? Question 6. Do you think chicanes or speed bumps are necessary to slow cyclists on the towpath? Question 7. Do you think cyclists should have to dismount at Wharf Road bridge? Question 8. Would you support the idea of a community garden at the back of the towpath near City Road Lock? Question 9. Where have you seen the consultation plans? Question 10. Please give us your comments on the scheme we have proposed. Additional Comments Consultation on Traffic Calming Scheme at City Road Lock - Feedback Results - March 2012 Introduction This report records and analyses feedback captured from the recent consultation event held between xx and 23rd March 2012. Information boards with suggestions for change were displayed on site (north of City Road Basin) and at Islington Library. Local residents and interest groups were invited to respond to 10 questions and provide feedback. We have included a graphic analysis of these responses to highlight certain trends and were additional comments have been provided, these have been presented verbatim. Consultation on Traffic Calming Scheme at City Road Lock - Feedback Results - -

London Borough of Islington Archaeological Priority Areas Appraisal

London Borough of Islington Archaeological Priority Areas Appraisal July 2018 DOCUMENT CONTROL Author(s): Alison Bennett, Teresa O’Connor, Katie Lee-Smith Derivation: Origination Date: 2/8/18 Reviser(s): Alison Bennett Date of last revision: 31/8/18 Date Printed: Version: 2 Status: Summary of Changes: Circulation: Required Action: File Name/Location: Approval: (Signature) 2 Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 5 2 Explanation of Archaeological Priority Areas .................................................................. 5 3 Archaeological Priority Area Tiers .................................................................................. 7 4 The London Borough of Islington: Historical and Archaeological Interest ....................... 9 4.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 9 4.2 Prehistoric (500,000 BC to 42 AD) .......................................................................... 9 4.3 Roman (43 AD to 409 AD) .................................................................................... 10 4.4 Anglo-Saxon (410 AD to 1065 AD) ....................................................................... 10 4.5 Medieval (1066 AD to 1549 AD) ............................................................................ 11 4.6 Post medieval (1540 AD to 1900 AD).................................................................... 12 4.7 Modern -

Nos. 116 to 130)

ESSEX SOCIETY FOR ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORY (Founded as the Essex Archaeological Society in 1852) Digitisation Project ESSEX ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORY NEWS DECEMBER 1992 TO AUTUMN/ WINTER 1999 (Nos. 116 to 130) 2014 ESAH REF: N1116130 Essex Archaeology and History News 0 December 1992 THE ESSEX SOCIETY FOR ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTOI~Y NEWSLETTER NUMBER 116 DECEMBER 1992 CONTENTS FROM THE PRESIDENT ............................ ... ....I 1993 PROGRAMME ..•...... ....... .. ...............•.. .2 SIR WILLIAM ADDISON ... .................... .........•2 VlC GRAY ..... ...... ..... ..... ........ .. .. .. ...... .4 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF TilE ESSEX COAST ..............•.. .....•4 ESSEX ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL CONGRESS: LOCAL HISTORY SYMPOSIUM .. .................... ...•.... .5 TilE ARCHAEOLOGY OF ESSEX TO AD 1500 .........•.........•... .5 NEW BOOKS ON ESSEX at DECEMBER 1992 ... ... .. ... ......•6 BOOK REVlEWS ....•. ..... .................. .........•6 RECENT PUBLICATIONS FROM THURROCK .. ........ ........... 7 SPY IN THE SKY ............................. •......... 7 COLCHESTER ARCHAEOLOGICAL REPORT ..•. ............... ...8 LIBRARY REPORT .... ......... ... .... .. ........ .......8 ESSEX JOURNAL ....... ............... .. ..... ........8 WARRIOR BURIAL FOUND AT STANWAY ..........................9 ENTENTE CORDIALE .................... ...........•......10 WORK OF THE TliE COUNTY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SECTION . .. ..........11 Editor: Paul Gilman 36 Rydal Way, Black Notley, Braintree, Essex, CM7 8UG Telephone: Braintree 331452 (home) Chelmsford 437636(work)