Introduction to the Handbook of American Indian Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROTO-SIOUAN PHONOLOGY and GRAMMAR Robert L. Rankin, Richard T

PROTO-SIOUAN PHONOLOGY AND GRAMMAR Robert L. Rankin, Richard T. Carter and A. Wesley Jones Univ. of Kansas, Univ. of Nebraska and Univ. of Mary The intellectual work on the Comparative Siouan Dictionary is relatively complete we and now have a picture of Proto-Siouan phonology and grammar. 1 The following is our Proto-Siouan pho neme inventory with a number of explanatory comments: labial dental palatal velar glottal STOPS Preaspirates: hp ht hk Postaspirates: ph th kh Glottals: p? t? k? ? Plain: p t k FRICATIVES voiceless: s g x h glottal: s? g? x? RESONANTS sonorant: w r y obstruent: W R VOWELS oral vowels: i u e 0 a nasal vowels: i- II ACCENT: 1'1 (high vs, non-high) & (possibly IAI falling) VOWEL LENGTH: I-I (+long) PREASPIRATED VOICELESS STOPS. We treat these as units be cause they incorporate a laryngeal feature that has attached it self to the stop, and because speakers today treat the reflexes of the series as single units for purposes of syllabification and segmentability. However, in pre-Proto-Siouan it is possible that there was no preaspirated series. The preaspirates pretty clearly arose as regular allophonic variants of plain voiceless stops preceding an accented vowel. This was pointed out by Dick Carter for Ofo in 1984. Even so, we have a number of lexical sets where it appears to be necessary to reconstruct plain voiceless stops in this environment also. Therefore, by the Proto-Siouan period the distinction between plain and preaspirated stops had appar- ently been phonemicized as shown by the following cognate sets: -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College Bible

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE BIBLE TRANSLATION AND LANGUAGE RENEWAL: A COLLABORATIVE APPROACH A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN APPLIED LINGUISTIC ANTHROPOLOGY By JOSH CAUDILL Norman, Oklahoma 2016 BIBLE TRANSLATION AND LANGUAGE RENEWAL: A COLLABORATIVE APPROACH A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY BY ___________________________________ Dr. Sean O’Neill, Chair ___________________________________ Dr. Racquel Sapien ___________________________________ Dr. Gus Palmer © Copyright by JOSH CAUDILL 2016 All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents Abstract vii Introduction 1 1. Identity and Agency 5 1.1. Identity and Essentialism 5 1.2. Language Ideology and Academic Authority 16 1.3. Religious Pluralism, or Not 23 2. Collaborative Research & Bible Translation 29 2.1. What are We Really Doing Here? 29 2.2. Benefits to the Linguist 32 2.3. Benefits to the Anthropologist 37 2.4. Benefits to the Speech Community Member 42 2.5. Benefits to the Theologian 45 3. Translation Philosophy 50 3.1. Translation: History and Philosophy 50 3.2. Translation and Beyond 55 3.3. Bible Translation, in Particular 58 4. Hebrew Poetry & Poetic Translation 63 5. Pawnee Texts and Translation 84 iv 5.1. Approaching Translation 84 5.2. Psalm 93 86 5.3. Generic Comparisons 91 5.4. The Limitations of This Project, and Moving Forward 95 Closing Remarks 96 Bibliography 100 v Tables & Figures Figure 3a: NLT Translation Spectrum 59 Table 4a: Psalm 119 77 Figure 5a: “A Woman Welcomes the Warriors” 89 vi Abstract Many indigenous languages face attrition globally as the languages of the West continue to grow in influence. -

Native American Languages, Indigenous Languages of the Native Peoples of North, Middle, and South America

Native American Languages, indigenous languages of the native peoples of North, Middle, and South America. The precise number of languages originally spoken cannot be known, since many disappeared before they were documented. In North America, around 300 distinct, mutually unintelligible languages were spoken when Europeans arrived. Of those, 187 survive today, but few will continue far into the 21st century, since children are no longer learning the vast majority of these. In Middle America (Mexico and Central America) about 300 languages have been identified, of which about 140 are still spoken. South American languages have been the least studied. Around 1500 languages are known to have been spoken, but only about 350 are still in use. These, too are disappearing rapidly. Classification A major task facing scholars of Native American languages is their classification into language families. (A language family consists of all languages that have evolved from a single ancestral language, as English, German, French, Russian, Greek, Armenian, Hindi, and others have all evolved from Proto-Indo-European.) Because of the vast number of languages spoken in the Americas, and the gaps in our information about many of them, the task of classifying these languages is a challenging one. In 1891, Major John Wesley Powell proposed that the languages of North America constituted 58 independent families, mainly on the basis of superficial vocabulary resemblances. At the same time Daniel Brinton posited 80 families for South America. These two schemes form the basis of subsequent classifications. In 1929 Edward Sapir tentatively proposed grouping these families into superstocks, 6 in North America and 15 in Middle America. -

Download Download

The Southern Algonquians and Their Neighbours DAVID H. PENTLAND University of Manitoba INTRODUCTION At least fifty named Indian groups are known to have lived in the area south of the Mason-Dixon line and north of the Creek and the other Muskogean tribes. The exact number and the specific names vary from one source to another, but all agree that there were many different tribes in Maryland, Virginia and the Carolinas during the colonial period. Most also agree that these fifty or more tribes all spoke languages that can be assigned to just three language families: Algonquian, Iroquoian, and Siouan. In the case of a few favoured groups there is little room for debate. It is certain that the Powhatan spoke an Algonquian language, that the Tuscarora and Cherokee are Iroquoians, and that the Catawba speak a Siouan language. In other cases the linguistic material cannot be positively linked to one particular political group. There are several vocabularies of an Algonquian language that are labelled Nanticoke, but Ives Goddard (1978:73) has pointed out that Murray collected his "Nanticoke" vocabulary at the Choptank village on the Eastern Shore, and Heckeweld- er's vocabularies were collected from refugees living in Ontario. Should the language be called Nanticoke, Choptank, or something else? And if it is Nanticoke, did the Choptank speak the same language, a different dialect, a different Algonquian language, or some completely unrelated language? The basic problem, of course, is the lack of reliable linguistic data from most of this region. But there are additional complications. It is known that some Indians were bilingual or multilingual (cf. -

2011 Pawnee Business Council Election- Candidate Bio’S

Pawnee Business Council President George E. Howell cutting the ribbon to the Skedee Bridge, along with (L to R) Dale Carter, Pawnee County Commissioner District 3/Chairman, J.T. Adams, Pawnee County Commissioner District 2, David Wilkins, Pawnee County Commissioner District 1, and Marshall Gover, Pawnee Business Council. PAGE 9 • 2011 Pawnee Business Council Election- Candidate Bio’s ......Starting on Page 4 • Millikin university Students Spend Spring Break at Pawnee nation ......Page 10 Page 2 Chaticks si Chaticks Special Election Edition -April 2011- Message From President George Howell Pawnee Dear Pawnee Tribal Members: First, on behalf of my family, I thank all those kind people who offered us prayers, gentle Business thoughts, condolences, contributions, food sharing, and keeping vigil upon the recent passing of my younger sister, Barbara Howell Chevarillo on February 17, 2011. The support shown our CounCil family was consoling. My family thanks you and appreciates your kindness. The Pawnee Nation has been busy on many fronts. On 3-15-2011, for example, a joint venture Members between the Pawnee Nation Transportation Department and Pawnee County Commissioners, culminated in the dedication of a completed bridge. This bridge replaces a very old and narrow structure was once known as, “the bridge where the goat was hung.” The new one is just short of President: the length of a football field. Along with Pawnee Nation members who live in this vicinity of the George E. Howell county, this access for safer passage also benefits other Pawnee County residents. This year, we again welcomed a group of Social Work students from Millikin University from Vice President: Decatur, Illinois. -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

The Prairie-Bird by Charles Augustus Murray Edited with an Introduction and Notes

Southern Illinois University Edwardsville SPARK Theses, Dissertations, and Culminating Projects Graduate School 1967 The prairie-bird by Charles Augustus Murray edited with an introduction and notes Donald Dean Miner Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Follow this and additional works at: https://spark.siue.edu/etd Recommended Citation Miner, Donald Dean, "The prairie-bird by Charles Augustus Murray edited with an introduction and notes" (1967). Theses, Dissertations, and Culminating Projects. 39. https://spark.siue.edu/etd/39 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at SPARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Culminating Projects by an authorized administrator of SPARK. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY Department of English THE PRAIRIE-BIRD by CHARLES AUGUSTUS MURRAY Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Donald Dean Miner A thesis presented to the Graduate Board of Southern Illinois University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts August, 1967 Edwardsville, Illinois TABLE OF CONTENTS Page EDITOR'S PREPACE ill EDITOR'S INTRODUCTION: CHARLES AUGUSTUS MURRAY AND THE WESTERN FRONTIER iv THE PRAIRIE-BIRD ........ complete text supplied in microfilm NOTES TO TEXT 1 SOURCES CONSULTED 36 ii PREFACE In January, 1844, Charles Augustus Murray's The Prairie-Bird was published in three volumes in London by R. Bentley. In 1845 It was reissued, this time as a single volume. The present edition is based on the 1845 printing. There has been no attempt to correct the numer ous typographical errors of that edition. -

Space in Languages in Mexico and Central America Carolyn O'meara

Space in languages in Mexico and Central America Carolyn O’Meara, Gabriela Pérez Báez, Alyson Eggleston, Jürgen Bohnemeyer 1. Introduction This chapter presents an overview of the properties of spatial representations in languages of the region. The analyses presented here are based on data from 47 languages belonging to ten Deleted: on literature covering language families in addition to literature on language isolates. Overall, these languages are located primarily in Mexico, covering the Mesoamerican Sprachbundi, but also extending north to include languages such as the isolate Seri and several Uto-Aztecan languages, and south to include Sumu-Mayangna, a Misumalpan language of Nicaragua. Table 1 provides a list of the Deleted: The literature consulted includes a mix of languages analyzed for this chapter. descriptive grammars as well as studies dedicated to spatial language and cognition and, when possible and relevant, primary data collected by the authors. Table 1 provides a Table 1. Languages examined in this chapter1 Family / Stock Relevant sub-branches Language Mayan Yucatecan Yucatecan- Yucatec Lacandon Mopan-Itzá Mopan Greater Cholan Yokot’an (Chontal de Tabasco) Tseltalan Tseltalan Tseltal Zinacantán Tsotsil Q’anjob’alan- Q’anjob’alan Q’anjob’al Chujean Jacaltec Otomanguean Otopame- Otomí Eastern Highland Otomí Chinantecan Ixtenco Otomí San Ildefonso Tultepec Otomí Tilapa Otomí Chinantec Palantla Chinantec 1 In most cases, we have reproduced the language name as used in the studies that we cite. However, we diverge from this practice in a few cases. One such case would be one in which we know firsthand what the preferred language name is among members of the language community. -

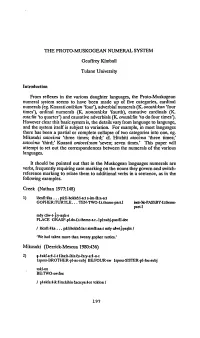

THE PROTO-MUSKOGEAN NUMERAL SYSTEM Geoffrey

THE PROTO-MUSKOGEAN NUMERAL SYSTEM Geoffrey Kimball Tulane University Introduction From reflexes in the various daughter languages, the Proto-Muskogean numeral system seems to have been made up of five categories, cardinal numerals ( eg. Koasati ostll:kan 'four'), adverbial numerals (K. onostll:kan 'four times'), ordinal numerals (K. stonosta:ka 'fourth), causative cardinals (K. osta:lin 'to quarter') and causative adverbials (K. onosta:lin 'to do four times'). However clear this basic system is, the details vary from language to language, and the system itself is subject to variation. For example, in most languages there has been a partial or complete collapse of two categories into one, eg. Mikasuki satoci:na 'three times; third;' cf. Hitchiti atoci:na 'three times;' satoci:na 'third;' Koasati ontocci:nan 'seven; seven times.' This paper will attempt to set out the correspondences between the numerals of the various languages. It should be pointed out that in the Muskogean languages numerals are verbs, frequently requiring case marking on the nouns they govern and switch- reference marking to relate them to additional verbs in a sentence, as in the following examples. Creek (Nathan 1977:148) 1) l6cafHka ••• pA:li-hokkM-a:t s-im-fa:n-a:t GOPHER:11JRTLE ... TEN-'IWO-f.t.theme-part.I iistr-3i>-PASS:BY-Wheme- partl mcy clw-t-j:y-al)k-s PLACE G RASP-pl.do-f.t.theme-s.r.-1 pl:subj-pastll-dec I 16cali:+ka ••• pA:lihokkO:la:t simf4:na:t mfy cJwtj:yal)ks I 'We had taken more than twenty gopher turtles.' Mikasuki (Derrick-Mescua 1980:436) 2) -

April/May 2012 Issue

Pawnee nation and Pawnee nation College employees recognized article on Page 12 Pawnee nation of oklahoma P.l. 102-477 Program Honored article on Page 4 April/May 2012 Page 2 Chaticks si Chaticks - APRIL/MAY 2012 Message from the President Pawnee Business CounCil NOWA! Members President: Greetings to all members of Marshall Gover the great Pawnee Nation. As we come up to this time Vice President: of year many people think of Charles “Buddy” Lone Chief Easter and associate it with Secretary: bunny rabbits, eggs and bas- Linda Jestes kets, but the true meaning of Easter is the resurrection of our Treasurer: Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. Roy Taylor The Pawnee People have always been spiritual people, Council Seat 1: believing and praying to Atius Richard Tilden Tirawahut. When the mission- Council Seat 2: aries came, the Pawnees were Karla Knife Chief not surprised that they brought with them their teachings of Council Seat 3: Jesus Christ. To the Pawnees Jimmy Fields it was very reasonable that the Father would have a Son. With Council Seat 4: that I want to wish everyone a Carol L Nuttle joyous holiday as we celebrate the true meaning of Easter. Chaticks si Chaticks Mother’s Day is also coming up. This is a time to celebrate, thank and pay tribute to all mothers. Our mothers are very special to us. So far this year we Pawnee Nation have enjoyed different functions celebrating mothers with a Peyote meeting Communications Manager and a handgame for a mother turning 90 years of age. Mothers have shown Toni Hill their pride and honored their young ones in the arena and in handgames. -

Walter Echo-Hawk

www.pawneenation.org JUNE 2020 YOUR 2020 VOTE COUNTS POSITIONS FOR May 29 - Deadline for Absentee Ballots PAWNEE BUSINESS COUNCIL June 4 - Candidate Forum 2 pm June 20 - Election Day !GO VOTE!June President 21 - Election Results Vice President June 22-24 Protest Deadline Treasurer July 2 - Issue Certification of Election July 6 - Inauguration Council Seat #1 2020 Special Election of the Pawnee Business Council Official Candidate List On May 14, 2020 the Pawnee Nation Election Commission met to review all candidate applications and background checks. There were zero (0) challenges filed. The following candidates have been deemed eligible and will be placed on the official 2020 Special Election of the Pawnee Business Council ballot for voting on June 20, 2020 at the Pawnee Nation Multi- Purpose Building. President Vice-President 2020 Special Election of the Pawnee Business Council Walter R. Echo-Hawk W. Bruce Pratt James E. Whiteshirt Official Candidate List Treasurer Member Seat #1 On May 14, 2020 the Pawnee Nation Election Commission met to review all candidate Tonette Ponkilla Pamela J. Cook applications and background checks. There were zero (0) challenges filed. The following Ralph Nordwall Cynthia Butler candidates have been deemed eligible and will be placed on the official 2020 Special Election of Carol Chapman the Pawnee Business Council ballot for voting on June 20, 2020 at the Pawnee Nation Multi- Purpose Building. Election Day is on June 20, 2020 Pawnee Nation Multi-Purpose Building President Vice-President 808 Morris Rd-Pawnee, Oklahoma 74058 For any questions please contact the Pawnee Nation Election Commission at Walter R. -

Siouan Tribes of the Ohio Valley

Siouan Tribes of the Ohio Valley: “Where did all those Indians come from?” Robert L. Rankin Professor Emeritus of Linguistics The University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS 66044 The fake General Custer quotation actually poses an interesting general question: How can we know the locations and movements of Native Peoples in pre- and proto-historic times? There are several kinds of evidence: 1. Evidence from the oral traditions of the people themselves. 2. Evidence from archaeology, relating primarily to material culture. 3. Evidence from molecular genetics. 4. Evidence from linguistics. The concept of FAMILY OF LANGUAGES • Two or more languages that evolved from a single language in the past. 1. Latin evolved into the modern Romance languages: French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Romanian, etc. 2. Ancient Germanic (unwritten) evolved into modern English, German, Dutch, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Icelandic, etc. Illustration of a language family with words from Germanic • English: HOUND HOUSE FOOT GREEN TWO SNOW EAR • Dutch: hond huis voet groen twee sneeuw oor • German: Hund Haus Fuss Grün Zwei Schnee Ohr • Danish: hund hus fod grøn to sne øre • Swedish: hund hus fot grön tvo snö öra • Norweg.: hund hus fot grønn to snø øre • Gothic: hus snaiws auso • Here, the clear correspondences among these very basic concepts and accompanying grammar signal a single common origin for all of these different languages, namely the original language of the Germanic tribes. Similar data for the Siouan language family. • DOG or • HORSE HOUSE FOOT TWO THREE FOUR