Full Text in Pdf Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Epibiotic Associates of Oceanic-Stage Loggerhead Turtles from the Southeastern North Atlantic

Acknowledgements We thank the biology students of the occasional leatherback nests in Brazil. Marine Turtle Federal University of Paraíba (Pablo Riul, Robson G. dos Newsletter 96:13-16. Santos, André S. dos Santos, Ana C. G. P. Falcão, Stenphenson Abrantes, MS Elaine Elloy), the marathon MARCOVALDI, M. Â. & G. G. MARCOVALDI. 1999. Marine runner José A. Nóbrega, and the journalist Germana turtles of Brazil: the history and structure of Projeto Bronzeado for the volunteer field work; the Fauna department TAMAR-IBAMA. Biological Conservation 91:35-41. of IBAMA/PB and Jeremy and Diana Jeffers for kindly MARCOVALDI, M.Â., C.F. VIEITAS & M.H. GODFREY. 1999. providing photos, and also Alice Grossman for providing Nesting and conservation management of hawksbill turtles the TAMAR protocols. The manuscript benefited from the (Eretmochelys imbricata) in northern Bahia, Brazil. comments of two referees. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 3:301-307. BARATA, P.C.R. & F.F.C. FABIANO. 2002. Evidence for SAMPAIO, C.L.S. 1999. Dermochelys coriacea (Leatherback leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) nesting in sea turtle), accidental capture. Herpetological Review Arraial do Cabo, state of Rio de Janeiro, and a review of 30:38-39. Epibiotic Associates of Oceanic-Stage Loggerhead Turtles from the Southeastern North Atlantic Michael G. Frick1, Arnold Ross2, Kristina L. Williams1, Alan B. Bolten3, Karen A. Bjorndal3 & Helen R. Martins4 1 Caretta Research Project, P.O. Box 9841, Savannah, Georgia 31412 USA. (E-mail: [email protected]) 2 Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Marine Biology Research Division, La Jolla, California 92093-0202, USA, (E-mail: [email protected]) 3 Archie Carr Center for Sea Turtle Research and Department of Zoology, University of Florida, P.O. -

Pelagic Sargassum Community Change Over a 40-Year Period: Temporal and Spatial Variability

Mar Biol (2014) 161:2735–2751 DOI 10.1007/s00227-014-2539-y ORIGINAL PAPER Pelagic Sargassum community change over a 40-year period: temporal and spatial variability C. L. Huffard · S. von Thun · A. D. Sherman · K. Sealey · K. L. Smith Jr. Received: 20 May 2014 / Accepted: 3 September 2014 / Published online: 14 September 2014 © The Author(s) 2014. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Pelagic forms of the brown algae (Phaeo- ranging across the Sargasso Sea, Gulf Stream, and south phyceae) Sargassum spp. and their conspicuous rafts are of the subtropical convergence zone. Recent samples also defining characteristics of the Sargasso Sea in the western recorded low coverage by sessile epibionts, both calcifying North Atlantic. Given rising temperatures and acidity in forms and hydroids. The diversity and species composi- the surface ocean, we hypothesized that macrofauna asso- tion of macrofauna communities associated with Sargas- ciated with Sargassum in the Sargasso Sea have changed sum might be inherently unstable. While several biological with respect to species composition, diversity, evenness, and oceanographic factors might have contributed to these and sessile epibiota coverage since studies were con- observations, including a decline in pH, increase in sum- ducted 40 years ago. Sargassum communities were sam- mer temperatures, and changes in the abundance and distri- pled along a transect through the Sargasso Sea in 2011 and bution of Sargassum seaweed in the area, it is not currently 2012 and compared to samples collected in the Sargasso possible to attribute direct causal links. Sea, Gulf Stream, and south of the subtropical conver- gence zone from 1966 to 1975. -

The Oceanic Crabs of the Genera Planes and Pachygrapsus

PROCEEDINGS OF THE UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM issued IflfNvA-QJsl|} by ^e SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION U. S. NATIONAL MUSEUM Vol. 101 Washington: 1951 No. 3272 THE OCEANIC CRABS OF THE GENERA PLANES AND PACHYGRAPSUS By FENNEB A. CHACE, Jr. ON September 17, 1492, at latitude approximately 28° N. and longitude 37° W., Columbus and his crew, during their first voyage to the New World, "saw much more weed appearing, like herbs from rivers, in which they found a live crab, which the Admiral kept. He says that these crabs are certain signs of land . "(Markham, 1893, p. 25). This is possibly the first recorded reference to oceanic crabs. Whether it refers to Planes or to the larger swimming crab, Portunus (Portunus) sayi (Gibbes), which is seldom found this far to the east, may be open to question, but the smaller and commoner Planes is frequently called Columbus's crab after this item in the discov erer's diary. Although these crabs must have been a source of wonder to mariners on the high seas in the past as they are today, the first adequate description of them did not appear until more than two centuries after Columbus's voyage when Sloane (1725, p. 270, pi. 245, fig. 1) recorded specimens from seaweed north of Jamaica. A short time later Linnaeus (1747, p. 137, pi. 1, figs. 1, a-b) described a similar form, which he had received from a Gflteborg druggist and which was reputed to have come from Canton. This specimen, which Linnaeus named Cancer cantonensis, may he the first record of the Pacific Planes cyaneus. -

![Genus Panopeus H. Milne Edwards, 1834 Key to Species [Based on Rathbun, 1930, and Williams, 1983] 1](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3402/genus-panopeus-h-milne-edwards-1834-key-to-species-based-on-rathbun-1930-and-williams-1983-1-1233402.webp)

Genus Panopeus H. Milne Edwards, 1834 Key to Species [Based on Rathbun, 1930, and Williams, 1983] 1

610 Family Xanthidae Genus Panopeus H. Milne Edwards, 1834 Key to species [Based on Rathbun, 1930, and Williams, 1983] 1. Dark color of immovable finger continued more or less on palm, especially in males. 2 Dark color of immovable finger not continued on palm 7 2. (1) Outer edge of fourth lateral tooth longitudinal or nearly so. P. americanus Outer edge of fourth lateral tooth arcuate 3 3. (2) Edge of front thick, beveled, and with transverse groove P. bermudensis Edge of front if thick not transversely grooved 4 4. (3) Major chela with cusps of teeth on immovable finger not reaching above imaginary straight line drawn between tip and angle at juncture of finger with anterior margin of palm (= length immovable finger) 5 Major chela with cusps of teeth near midlength of immovable finger reaching above imaginary straight line drawn between tip and angle at juncture of finger with anterior margin of palm (= length immovable finger) 6 5. (4) Coalesced anterolateral teeth 1-2 separated by shallow rounded notch, 2 broader than but not so prominent as 1; 4 curved forward as much as 3; 5 much smaller than 4, acute and hooked forward; palm with distance between crest at base of movable finger and tip of cusp lateral to base of dactylus 0.7 or less length of immovable finger P. herbstii Coalesced anterolateral teeth 1-2 separated by deep rounded notch, adjacent slopes of 1 and 2 about equal, 2 nearly as prominent as 1; 4 not curved forward as much as 3; 5 much smaller than 4, usually projecting straight anterolaterally, sometimes slightly hooked; distance between crest of palm and tip of cusp lateral to base of movable finger 0.8 or more length of immovable finger P. -

Molecular Phylogeny of the Western Atlantic Species of the Genus Portunus (Crustacea, Brachyura, Portunidae)

Blackwell Publishing LtdOxford, UKZOJZoological Journal of the Linnean Society0024-4082The Lin- nean Society of London, 2007? 2007 1501 211220 Original Article PHYLOGENY OF PORTUNUS FROM ATLANTICF. L. MANTELATTO ET AL. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2007, 150, 211–220. With 3 figures Molecular phylogeny of the western Atlantic species of the genus Portunus (Crustacea, Brachyura, Portunidae) FERNANDO L. MANTELATTO1*, RAFAEL ROBLES2 and DARRYL L. FELDER2 1Laboratory of Bioecology and Crustacean Systematics, Department of Biology, FFCLRP, University of São Paulo (USP), Ave. Bandeirantes, 3900, CEP 14040-901, Ribeirão Preto, SP (Brazil) 2Department of Biology, Laboratory for Crustacean Research, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, LA 70504-2451, USA Received March 2004; accepted for publication November 2006 The genus Portunus encompasses a comparatively large number of species distributed worldwide in temperate to tropical waters. Although much has been reported about the biology of selected species, taxonomic identification of several species is problematic on the basis of strictly adult morphology. Relationships among species of the genus are also poorly understood, and systematic review of the group is long overdue. Prior to the present study, there had been no comprehensive attempt to resolve taxonomic questions or determine evolutionary relationships within this genus on the basis of molecular genetics. Phylogenetic relationships among 14 putative species of Portunus from the Gulf of Mexico and other waters of the western Atlantic were examined using 16S sequences of the rRNA gene. The result- ant molecularly based phylogeny disagrees in several respects with current morphologically based classification of Portunus from this geographical region. Of the 14 species generally recognized, only 12 appear to be valid. -

Shrimps, Lobsters, and Crabs of the Atlantic Coast of the Eastern United States, Maine to Florida

SHRIMPS, LOBSTERS, AND CRABS OF THE ATLANTIC COAST OF THE EASTERN UNITED STATES, MAINE TO FLORIDA AUSTIN B.WILLIAMS SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS Washington, D.C. 1984 © 1984 Smithsonian Institution. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Williams, Austin B. Shrimps, lobsters, and crabs of the Atlantic coast of the Eastern United States, Maine to Florida. Rev. ed. of: Marine decapod crustaceans of the Carolinas. 1965. Bibliography: p. Includes index. Supt. of Docs, no.: SI 18:2:SL8 1. Decapoda (Crustacea)—Atlantic Coast (U.S.) 2. Crustacea—Atlantic Coast (U.S.) I. Title. QL444.M33W54 1984 595.3'840974 83-600095 ISBN 0-87474-960-3 Editor: Donald C. Fisher Contents Introduction 1 History 1 Classification 2 Zoogeographic Considerations 3 Species Accounts 5 Materials Studied 8 Measurements 8 Glossary 8 Systematic and Ecological Discussion 12 Order Decapoda , 12 Key to Suborders, Infraorders, Sections, Superfamilies and Families 13 Suborder Dendrobranchiata 17 Infraorder Penaeidea 17 Superfamily Penaeoidea 17 Family Solenoceridae 17 Genus Mesopenaeiis 18 Solenocera 19 Family Penaeidae 22 Genus Penaeus 22 Metapenaeopsis 36 Parapenaeus 37 Trachypenaeus 38 Xiphopenaeus 41 Family Sicyoniidae 42 Genus Sicyonia 43 Superfamily Sergestoidea 50 Family Sergestidae 50 Genus Acetes 50 Family Luciferidae 52 Genus Lucifer 52 Suborder Pleocyemata 54 Infraorder Stenopodidea 54 Family Stenopodidae 54 Genus Stenopus 54 Infraorder Caridea 57 Superfamily Pasiphaeoidea 57 Family Pasiphaeidae 57 Genus -

Invertebrate ID Guide

11/13/13 1 This book is a compilation of identification resources for invertebrates found in stomach samples. By no means is it a complete list of all possible prey types. It is simply what has been found in past ChesMMAP and NEAMAP diet studies. A copy of this document is stored in both the ChesMMAP and NEAMAP lab network drives in a folder called ID Guides, along with other useful identification keys, articles, documents, and photos. If you want to see a larger version of any of the images in this document you can simply open the file and zoom in on the picture, or you can open the original file for the photo by navigating to the appropriate subfolder within the Fisheries Gut Lab folder. Other useful links for identification: Isopods http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-33/htm/doc.html http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-48/htm/doc.html Polychaetes http://web.vims.edu/bio/benthic/polychaete.html http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-34/htm/doc.html Cephalopods http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-44/htm/doc.html Amphipods http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-67/htm/doc.html Molluscs http://www.oceanica.cofc.edu/shellguide/ http://www.jaxshells.org/slife4.htm Bivalves http://www.jaxshells.org/atlanticb.htm Gastropods http://www.jaxshells.org/atlantic.htm Crustaceans http://www.jaxshells.org/slifex26.htm Echinoderms http://www.jaxshells.org/eich26.htm 2 PROTOZOA (FORAMINIFERA) ................................................................................................................................ 4 PORIFERA (SPONGES) ............................................................................................................................................... 4 CNIDARIA (JELLYFISHES, HYDROIDS, SEA ANEMONES) ............................................................................... 4 CTENOPHORA (COMB JELLIES)............................................................................................................................ -

Hermit Crabs - Paguridae and Diogenidae

Identification Guide to Marine Invertebrates of Texas by Brenda Bowling Texas Parks and Wildlife Department April 12, 2019 Version 4 Page 1 Marine Crabs of Texas Mole crab Yellow box crab Giant hermit Surf hermit Lepidopa benedicti Calappa sulcata Petrochirus diogenes Isocheles wurdemanni Family Albuneidae Family Calappidae Family Diogenidae Family Diogenidae Blue-spot hermit Thinstripe hermit Blue land crab Flecked box crab Paguristes hummi Clibanarius vittatus Cardisoma guanhumi Hepatus pudibundus Family Diogenidae Family Diogenidae Family Gecarcinidae Family Hepatidae Calico box crab Puerto Rican sand crab False arrow crab Pink purse crab Hepatus epheliticus Emerita portoricensis Metoporhaphis calcarata Persephona crinita Family Hepatidae Family Hippidae Family Inachidae Family Leucosiidae Mottled purse crab Stone crab Red-jointed fiddler crab Atlantic ghost crab Persephona mediterranea Menippe adina Uca minax Ocypode quadrata Family Leucosiidae Family Menippidae Family Ocypodidae Family Ocypodidae Mudflat fiddler crab Spined fiddler crab Longwrist hermit Flatclaw hermit Uca rapax Uca spinicarpa Pagurus longicarpus Pagurus pollicaris Family Ocypodidae Family Ocypodidae Family Paguridae Family Paguridae Dimpled hermit Brown banded hermit Flatback mud crab Estuarine mud crab Pagurus impressus Pagurus annulipes Eurypanopeus depressus Rithropanopeus harrisii Family Paguridae Family Paguridae Family Panopeidae Family Panopeidae Page 2 Smooth mud crab Gulf grassflat crab Oystershell mud crab Saltmarsh mud crab Hexapanopeus angustifrons Dyspanopeus -

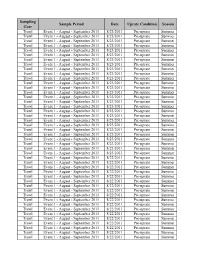

St. Lucie, Units 1 and 2

Sampling Sample Period Date Uprate Condition Season Gear Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event -

Anomura and Brachyura

Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 1771 December 1990 A GUIDE TO DECAPOD CRUSTACEA FROM THE CANADIAN ATLANTIC: ANOMURA AND BRACHYURA Gerhard W. Pohle' Biological Sciences Branch Department of Fisheries and Oceans Biological Station St. Andrews, New Brunswick EOG 2XO Canada ,Atlantic Reference Centre, Huntsman Marine Science Centre St. Andrews, New Brunswick EOG 2XO Canada This is the two hundred and eleventh Technical Report from the Biological Station, St. Andrews, N. B. ii . © Minister of Supply and Services Canada 1990 Cat. No. Fs 97-611771 ISSN 0706-6457 Correct citation for this publication: Pohle, G. W. _1990. A guide to decapod Crustacea from the Canadian Atlantic: Anorrora and Brachyura. Can. Tech. Rep. Fish. Aquat. SCi. 1771: iv + 30 p. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract ..............................................................." iv Introduction 1 How to use this guide " 2 General morphological description 3 How to distinguish anomuran and brachyuran decapods 5 How to distinguish the families of anornuran crabs 6 Family Paguridae Pagurus acadianus Benedict, 1901 ........................................ .. 7 Pagurus arcuatus Squires, 1964 .......................................... .. 8 Pagurus longicarpus Say, 1817 9 Pagurus politus (Smith, 1882) 10 Pagurus pubescens (Kmyer, 1838) 11 Family Parapaguridae P.arapagurus pilosimanus Smith, 1879 12 Family Lithodidae Lithodes maja (Linnaeus, 1758) 13 Neolithodes grimaldii (Milne-Edwards and Bouvier, 1894) 14 Neolithodes agassizii (Smith 1882) 14 How to distinguish the families of brachyuran crabs 15 Family Majidae Chionoecetes opilio (Fabricius, 1780) 17 Hyas araneus (Linnaeus, 1758) 18 Hyas coarctatus Leach, 1815 18 Libinia emarginata Leach, 1815 19 Family Cancridae Cancer borealis Stimpson, 1859 20 Cancer irroratus Say, 1817 20 Family Geryonidae Chaceon quinquedens (Smith, 1879) 21 Family Portunidae Ovalipes ocellatus (Herbst,- 1799) 22 Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896 ................................... -

Coral Cap Species of Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary

CORAL CAP SPECIES OF FLOWER GARDEN BANKS NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY Classification Common name Scientific Name Bacteria Schizothrix calcicola CORAL CAP SPECIES OF FLOWER GARDEN BANKS NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY Classification Common name Scientific Name Algae Brown Algae Dictyopteris justii Forded Sea Tumbleweeds Dictyota bartayresii Dictyota cervicornis Dictyota dichotoma Dictyota friabilis (pfaffii) Dictyota humifusa Dictyota menstrualis Dictyota pulchella Ectocarpus elachistaeformis Leathery Lobeweeds, Encrusting Lobophora variegata Fan-leaf Alga Peacock's Tail Padina jamaicensis Padina profunda Padina sanctae-crucis Rosenvingea intricata Gulf Weed, Sargassum Weed Sargassum fluitans White-vein Sargassum Sargassum hystrix Sargasso Weed Sargassum natans Spatoglossum schroederi Sphacelaria tribuloides Sphacelaria Rigidula Leafy Flat-blade Alga Stypopodium zonale Green Algae Papyrus Print Alga Anadyomene stellata Boodelopsis pusilla Bryopsis plumosa Bryopsis pennata Caulerpa microphysa Caulerpa peltata Green Grape Alga Caulerpa racemosa v. macrophysa Cladophora cf. repens Cladophoropsis membranacea Codium decorticatum Dead Man’s Fingers Codium isthmocladum Codium taylori Hair Algae Derbesia cf. marina Entocladia viridis Large Leaf Watercress Alga Halimeda discoidea Halimeda gracilis Green Net Alga Microdictyon boergesenii Spindleweed, Fuzzy Tip Alga Neomeris annulata Struvea sp. CORAL CAP SPECIES OF FLOWER GARDEN BANKS NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY Classification Common name Scientific Name Udotea flabellum Ulva lactuca Ulvella lens Elongated -

Decapoda (Crustacea) of the Gulf of Mexico, with Comments on the Amphionidacea

•59 Decapoda (Crustacea) of the Gulf of Mexico, with Comments on the Amphionidacea Darryl L. Felder, Fernando Álvarez, Joseph W. Goy, and Rafael Lemaitre The decapod crustaceans are primarily marine in terms of abundance and diversity, although they include a variety of well- known freshwater and even some semiterrestrial forms. Some species move between marine and freshwater environments, and large populations thrive in oligohaline estuaries of the Gulf of Mexico (GMx). Yet the group also ranges in abundance onto continental shelves, slopes, and even the deepest basin floors in this and other ocean envi- ronments. Especially diverse are the decapod crustacean assemblages of tropical shallow waters, including those of seagrass beds, shell or rubble substrates, and hard sub- strates such as coral reefs. They may live burrowed within varied substrates, wander over the surfaces, or live in some Decapoda. After Faxon 1895. special association with diverse bottom features and host biota. Yet others specialize in exploiting the water column ment in the closely related order Euphausiacea, treated in a itself. Commonly known as the shrimps, hermit crabs, separate chapter of this volume, in which the overall body mole crabs, porcelain crabs, squat lobsters, mud shrimps, plan is otherwise also very shrimplike and all 8 pairs of lobsters, crayfish, and true crabs, this group encompasses thoracic legs are pretty much alike in general shape. It also a number of familiar large or commercially important differs from a peculiar arrangement in the monospecific species, though these are markedly outnumbered by small order Amphionidacea, in which an expanded, semimem- cryptic forms. branous carapace extends to totally enclose the compara- The name “deca- poda” (= 10 legs) originates from the tively small thoracic legs, but one of several features sepa- usually conspicuously differentiated posteriormost 5 pairs rating this group from decapods (Williamson 1973).