C13 V.I Title.P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'aula D'idioma Com a Mitjà D'integració I D'enriquiment

L’AULA D’IDIOMA COM A MITJÀ D’INTEGRACIÓ I D’ENRIQUIMENT MULTICULCULTURAL José Luis Bartolomé Sánchez Curs 2004-2005 Centre de treball: IES Montsacopa (Olot, Garrotxa) Especialitat: Llengua anglesa Supervisió: Neus Serra (Servei Inspecció Delegació Territorial d’Educació de Girona) Llicència d’estudis retribuïda concedida pel Departament d’Educació de la Generalitat, Resolució del 16 de juliol de 2004 (DOGC núm. 4182 de 26.7. 2004) “The White Man Drew a Small Circle” The white man drew a small circle in the sand and told the red man, 'This is what the Indian knows,' and drawing a big circle around the small one, 'This is what the white man knows.' The Indian took the stick and swept an immense ring around both circles: 'This is where the white man and the red man know nothing.' Carl Sandburg « L'home blanc va dibuixar un cercle petit » L'home blanc va dibuixar un cerce petit a la sorra i va dir al pell roja: "Això és els que coneixeu els indis" i tot seguit va dibuixar un cercle gran al voltant del petit: "Això és el que coneixem els homes blancs." L'indi va agafar el pal i va escombrar un enorme cercle al voltant dels altres dos: "Això és on ni l'home blanc ni el pell roja no coneixen gens". 2 3 4 5 Índex Pàgina Introducció 7 Greencards for Cultural Integration 11 Readers 113 - Around the world in ten Tintin books 118 - Australia 129 - America 139 - Far and Middle East 155 - Africa 177 - Far East. China & India 217 Pop Songs 249 Movies 357 Conclusions 428 Bibliografia 433 6 INTRODUCCIÓ 7 L'experiència personal dels darrers anys com a docent d'institut en un municipi amb un augment espectacular de l'arribada de famílies i alumnes d'altres països m'ha fet veure que l'entrebanc principal de contacte amb aquestes persones -l'idioma- resulta de vegades paradoxal. -

Is It Time to Bring Back Adjournments? the United States’ Largest Chess Specialty Retailer

GOLD, SILVER, AND BRONZE AT THE WORLD CADETS February 2020 | USChess.org Is It Time To Bring Back Adjournments? The United States’ Largest Chess Specialty Retailer 888.51.CHESS (512.4377) www.USCFSales.com Keep It Simple 1.d4 Beyond Material ^ŽůŝĚĂŶĚ^ƚƌĂŝŐŚƞŽƌǁĂƌĚŚĞƐƐKƉĞŶŝŶŐZĞƉĞƌƚŽŝƌĞĨŽƌtŚŝƚĞ /ŐŶŽƌĞƚŚĞ&ĂĐĞsĂůƵĞŽĨzŽƵƌWŝĞĐĞƐĂŶĚŝƐĐŽǀĞƌƚŚĞ Christof Sielecki 432 pages - $29.95 /ŵƉŽƌƚĂŶĐĞŽĨdŝŵĞ͕^ƉĂĐĞĂŶĚWƐLJĐŚŽůŽŐLJŝŶŚĞƐƐ ^ŝĞůĞĐŬŝ͛ƐƌĞƉĞƌƚŽŝƌĞǁŝƚŚϭ͘ĚϰŵĂLJďĞĞǀĞŶĞĂƐŝĞƌƚŽ Davorin Kuljasevic 336 pages - $24.95 ŵĂƐƚĞƌƚŚĂŶŚŝƐϭ͘ĞϰƌĞĐŽŵŵĞŶĚĂƟŽŶƐ͕ďĞĐĂƵƐĞŝƚŝƐƐƵĐŚĂ &ŽƌŐĞƚĂďŽƵƚĐŽƵŶƟŶŐƚŚĞƐƚĂƟĐǀĂůƵĞŽĨLJŽƵƌƉŝĞĐĞƐ͕ůĞĂƌŶ ĐŽŚĞƌĞŶƚƐLJƐƚĞŵ͗ƚŚĞŵĂŝŶĐŽŶĐĞƉƚŝƐĨŽƌtŚŝƚĞƚŽƉůĂLJϭ͘Ěϰ͕ ƚŚĞǀŝƚĂůƐŬŝůůŽĨƚĂŬŝŶŐĐĂůĐƵůĂƚĞĚƌŝƐŬƐ͘ Ϯ͘EĨϯ͕ϯ͘Őϯ͕ϰ͘ŐϮ͕ϱ͘ϬͲϬĂŶĚŝŶŵŽƐƚĐĂƐĞƐϲ͘Đϰ͘ ͞ĞƐĞƌǀĞƐĂǁŝĚĞĂƵĚŝĞŶĐĞ͘KŶĞŽĨƚŚĞďĞƐƚŬƐ/ŚĂǀĞ ͞Ɛ/ƚŚŝŶŬƚŚĂƚ/ƐŚŽƵůĚŬĞĞƉŵLJĂĚǀŝĐĞ͚ƐŝŵƉůĞ͕͛/ǁŽƵůĚƐĂLJ ƌĞĂĚƚŚŝƐLJĞĂƌ͘͟ Et͊ ͚ũƵƐƚŐĞƚŝƚ͛͊͟ʹ'D'ůĞŶŶ&ůĞĂƌ /D:ŽŚŶŽŶĂůĚƐŽŶ New In Chess 2019#8 <ĂƵĨŵĂŶ͛ƐEĞǁZĞƉĞƌƚŽŝƌĞĨŽƌůĂĐŬĂŶĚtŚŝƚĞ ZĞĂĚďLJĐůƵďƉůĂLJĞƌƐŝŶϭϭϲĐŽƵŶƚƌŝĞƐϭϬϲƉĂŐĞƐͲ$14.99 ŽŵƉůĞƚĞ͕^ŽƵŶĚĂŶĚhƐĞƌͲĨƌŝĞŶĚůLJŚĞƐƐKƉĞŶŝŶŐZĞƉĞƌƚŽŝƌĞ DĂŐŶŝĮĐĞŶƚƐƚƵī͕ĨƵůůLJĂĐĐĞƐƐŝďůĞĨŽƌĂŵĂƚĞƵƌƐ͊DĂŐŶƵƐ Larry Kaufman 464 pages - $32.95 ĂƌůƐĞŶ͛ƐƚƌĂŝŶĞƌƌĞǀĞĂůƐŚŽǁůƉŚĂĞƌŽƌĞǀŽůƵƟŽŶŝnjĞĚƚŚĞ ůƵĐŝĚůLJĞdžƉůĂŝŶĞĚ͕ƌĞĂĚLJͲƚŽͲŐŽĂŶĚĞĂƐLJͲƚŽͲĚŝŐĞƐƚ ƉůĂLJŽĨŚŝƐďŽƐƐ͘ĂƌĞͲĚĞǀŝůĂŶŝŝůƵďŽǀĂŶŶŽƚĂƚĞƐŚŝƐǁŝŶ ƌĞƉĞƌƚŽŝƌĞǁŝƚŚƐŽƵŶĚ͕ƉƌĂĐƟĐĂůůŝŶĞƐƚŚĂƚĚŽŶŽƚŐŽŽƵƚŽĨ ŽĨƚŚĞLJĞĂƌ͘tĞƐůĞLJ^Ž͗ŚŽǁ/ďĞĂƚƚŚĞtŽƌůĚŚĂŵƉŝŽŶĂƚ ĚĂƚĞƌĂƉŝĚůLJ͘^ƵŝƚĂďůĞĨŽƌŵĂƐƚĞƌƐǁŚŝůĞƉĞƌĨĞĐƚůLJĂĐĐĞƐƐŝďůĞ &ŝƐĐŚĞƌZĂŶĚŽŵ͘:ƵĚŝƚWŽůŐĂƌ͛ƐĞdžĐůƵƐŝǀĞĐŽůƵŵŶ͘dŚĞůŝƚnj ĨŽƌĂŵĂƚĞƵƌƐ͘zŽƵĂůǁĂLJƐŐĞƚƚǁŽŽƉƟŽŶƐĂŶĚĚŽŶ͛ƚŚĂǀĞ tŚŝƐƉĞƌĞƌDĂdžŝŵůƵŐLJ͗ƉƌĂĐƟĐĂůĞŶĚŐĂŵĞŝŵƉƌŽǀĞŵĞŶƚ͘ -

Kramnik in Action Lithuania on Top Huge Success On-Line

Daily News of Torino Olympiad May 24 /2006. Kramnik in action Lithuania on top his time we shall start with match was something like a civil war since ladie’s competition whe- seven out of eight players were Russians! A re some dramatical chan- second victory was scored by Bareev against ges occured in yesterday’s Lutz, Morozevich couldn’t escape from per- round. In match number petual check against Jussupow, but Ruble- one China won convincingly against France vsky against Graf unexpectedly lost an en- (2,5:0,5),T but this was not enough to take the dgame which looked rather eaqual, at least lead because in match number two the Bal- at fi rst sight. tic derby fi nished with a maximal victory of Aft er such a modest result the leader was Lithuanian team who took the lead wit still a joined by two teams who managed to cash perfect score! Russia won with the same re- 3,5 points: China and Uzbekistan winners sult against Poland and joined China. Both against Slovakia and Australia, and by actual teams have 8,5 points. Half a point behind champions of Ukraina victorious against them are Ukraine (3:0 against Mongolia) SCG (Serbia&Montengro) with 3:1.All these and Romania (2,5:0,5 against Italy «A»). teams have 10,5 points. Half a point behind Th ree more teams came closer to the top them are Netherlands, 3:1 victory against with 7,5 points: USA, Bulgaria and Israel af- Turkey and Greece, 2,5:1,5 against Poland. -

Fide Lieflet 1-5 Working

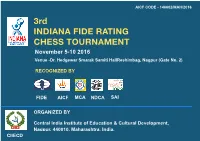

AICF CODE - 146602/MAH/2016 3rd INDIANA FIDE RATING CHESS TOURNAMENT November 5-10 2016 Venue -Dr. Hedgewar Smarak Samiti HallReshimbag, Nagpur (Gate No. 2) RECOGNIZED BY FIDE AICF MCA NDCA SAI ORGANIZED BY " Central India Institute of Education & Cultural Development, Nagpur, 440010, Maharashtra, India. CIIECD CASH PRIZES TO TOP 20 PLAYERS 1st Prize 2nd Prize 3rd Prize 4th Prize 5th Prize 6th Prize 7th Prize 8th Prize 9th Prize 10th Prize Rs. 51000/- Rs. 31000/- Rs. 21000/- Rs. 16000/- Rs. 15000/- Rs. 13000/- Rs. 12500/- Rs. 12000/- Rs.11500/- Rs. 10000/- 11th Prize 12th Prize 13th Prize 14th Prize 15th Prize 16th Prize 17th Prize 18th Prize 19th Prize 20th Prize Rs. 7500/- Rs. 7000/- Rs. 6500/- Rs. 6000/- Rs. 5500/- Rs. 5000/- Rs. 4500/- Rs. 4000/- Rs. 3500/- Rs. 3000/- " CASH PRZES FOR RATING 1601 - 1800 CASH PRZES FOR RATING 1401 - 1600 1st Prize 2nd Prize 3rd Prize 1st Prize 2nd Prize 3rd Prize Rs. 4000/- Rs. 3000/- Rs. 2500/- Rs. 4000/- Rs. 3000/- Rs. 2500/- PRZES FOR RATING 1201 - 1400 PRZES FOR RATING 1001 - 1200 1st Prize 2nd Prize 3rd Prize 1st Prize 2nd Prize 3rd Prize Rs. 4000/- Rs. 3000/- Rs. 2500/- Rs. 4000/- Rs. 3000/- Rs. 2500/- " BEST VETERAN BEST UNRATED BEST FEMALE 1st Prize 2nd Prize 1st Prize 2nd Prize 1st Prize 2nd Prize Rs. 3000/- Rs. 2500/- Rs. 3000/- Rs. 2500/- Rs. 3000/- Rs. 2500/- " A. SPECIAL PRIZES 1. Designer Trophies for top Five players in each category viz. U-13, U-11, U9, U-7 ( Players are eligible for trophy and prizes for the age group from which he/she belongs) 2. -

Aicfconsitutionbyelawsamende

- 1 - THE CONSTITUTION AND BYE LAWS OF ALL INDIA CHESS FEDERATION (Regd. No.125 of 1958) (Regulated by the Tamilnadu Societies Registration Act 1975) *** Amended as on 25th June, 2017 ================================================ 1. The Name of the Society : All India Chess Federation shortly called as “AICF”. The word Federation shall not be used in their name by any State Association or Unit. 2. The Address of the Registered Society: Hall No.70 Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium Periamet, Chennai 600 003. 3. The formation of the Society: All India Chess Federation was formed on 12th December 1958 and registered as a Society under Societies Registration act 1860 bearing Regn. No.125 of 1958 with the Registrar of Assurances, Madras - Chingleput. As per Section 53 of Act 27 of 1975, the Society is now regulated by the Tamilnadu Societies Registration Act 1975. 4. The Society is within the Jurisdiction of Registrar of Society: The Society is now functioning under the jurisdiction of the Registrar of societies Chennai Central”. The Jurisdiction shall be as decided by Registration Department, Government of Tamilnadu” from time to time. 5. The business hours of the Society : Between 10.30 A.M. to 5.30 P.M. on all Working days except Sundays and Government holidays. 6. The objects of the Society: The objects of All India Chess Federation shall be – (a) To promote the game of Chess to inculcate a sense of discipline amongst the players, to increase their proficiency, to foster brotherhood among the players and to promote a chess culture. - 2 - (b) To maintain general control over the chess activities in India in accordance with this Constitution and the Rules and Regulations of the International Chess Federation (FIDE) in force from time to time. -

Wrestling Is Part of the Martial Arts

TOMSK POLYTECHNIС UNIVERSITY M.V. Netesova E.A. Leksina SPORT FOR PROFESSIONALS STUDENT’S BOOK Recommended for publishing by the Editorial Board of the Tomsk Polytechnic University Tomsk Polytechnic University Publishing House 2010 Федеральное агентство по образованию Государственное образовательное учреждение высшего профессионального образования «НАЦИОНАЛЬНЫЙ ИССЛЕДОВАТЕЛЬСКИЙ ТОМСКИЙ ПОЛИТЕХНИЧЕСКИЙ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ» М.В. Нетесова Е.A. Лексина СПОРТ ДЛЯ ПРОФЕССИОНАЛОВ Рекомендовано в качестве учебного пособия Редакционно-издательским советом Томского политехнического университета Издательство Томского политехнического университета 2010 2 УДК 802.0(075.8) ББК Ш143.21-923 Н571 Нетесова М.В. Н571 Спорт для профессионалов: учебное пособие / М.В. Нетесова, Е.A. Лексина - Томск: Изд-во Томского политехнического университета, 2010. - 84 с. Учебное пособие предназначено для студентов факультета физической культуры Томского Политехнического Университета и ВУЗов России. Учебное пособие состоит из профессионально-ориентированных текстов по теме спорт и физическая культура. Ко всем учебным текстам авторами разработаны упражнения, которые предполагают индивидуальную, парную и групповую работу. Текстовый материал пособия позволит студентам получить профессионально-ориентированную информацию на английском языке и пополнить словарь профессиональных терминов по своей специальности. Тексты являются аутентичными и отобраны из современных англоязычных источников (в том числе Интернет сайтов). УДК 802.0(075.8) ББК Ш143.21-923 Рецензенты Кандидат педагогических наук, доцент, зав. каф. теории и методики преподавания иностранных языков ТГПУ О. Н. Игна Кандидат философских наук каф. английской филологии факультета иностранных языков ТГУ И. А. Черепанова © ГОУ ВПО «Национально исследовательский Томский политехнический университет», 2010 © Нетесова М.В., Лексина Е.А., 2010 © Оформление. Издательство Томского политехнического университета, 2010 3 TO THE STUDENTS This book is for you if you are studying sport or if you work in the sport industry. -

Viswanathan Anand Addresses Online Session for SAI Officials from Germany , Says the Apex Sports Body Can Contribute Greatly in Promoting Chess in India

Viswanathan Anand addresses online session for SAI officials from Germany , says the apex sports body can contribute greatly in promoting chess in India New Delhi, April 22: Indian sports legend Viswanathan Anand who is a former multiple-time world champion, former World Number 1 and a Rajiv Gandhi Khel Ratna Awardee, today addressed the newly-appointed Assistant Directors of the Sports Authority of India in a special online session from Germany. Speaking at the session he shared his experience of nearly four decades of playing chess, how the game has changed over the years with advanced technology and also how the Sports Authority of India can help in building up budding chess players in the country. Addressing the newly-appointed administrators, Anand said Sports Authority of India can make a big difference towards promoting chess as a sport in India. “SAI already has facilities and infrastructure for training. It would be of great help to budding chess players if SAI could give them access to special Chess Computers in these facilities since most players don't have access to these.” Anand, who has been in Germany since the Corona pandemic broke our and lockdown was announced in various countries, including India, has said that he goes for long walks during this lean period. However, he is also known to take up physical fitness sessions all year round. Speaking about the importance of fitness in a sport like Chess which is perceived as a sport of the mind, Anand urged young chess players to go to SAI centres and keep their physical fitness at par with their mental fitness, “Fitness is not a problem when you are young, but it becomes a factor when you start getting older. -

GM Fabiano Caruana

;GDD=?=;@=KK>AF9D>GMJ2ML%JAG?J9F<=N9DD=QKF9HKO=:KL=JK>AF9D>GMJKLJ=9C June 2018 | USChess.org GM Fabiano Caruana America’s World Championship Candidate Winning in the Chess Opening Super Chess Kids NEW! 700 Ways to Ambush Your Opponent Win Like the World’s Young Champions! Nikolay Kalinichenko JLJ+".AEHJ;OK GJJ+".AEGL;OK *-/#)%2./*''0*)*/-+.)/-$&.; )4++-*#$)#..$(+-*3()/*-6*2)"./-.: '$)$#)&*'46.5+'$)./#$.)+').#$) $)./-20*)'(/-$')*/-*(*'"(.*)$)/ NEW! /#*+)$)")#*4+'6*2'#3)$(+-*3; (./-.92/.'/-*("(.+'6$)-)/2)-AGJ $/#/#$.+-.)/$)/#$.4''A*-")$7**&9 #(+$*).#$+.-*2)/#4*-';$/#(*-/#)GFF/./.; 3)/2-*2.'2+'6-.4$''4$)(*-"(.9)(*- ?4*)-2'#..$)./-20*)**&93-6(2#-*(A -+$'68 *-4$-)"*+'6-.; ()*-''+'6-.2+/* '*HFFF;@BIM Dirk Schuh Play 1...d6 Against Everything My System & Chess Praxis A Compact and Ready-to-use Black Repertoire for Club Players ! Erik Zude & Jörg Hickl HNN+".AEHJ;OK Aron Nimzowitsch KML+".BEHO;95 3'*+6*2-+*.$0*)4$/#./-*)"./)-(*3.) )'2.=#'*&>)=)/# $./*-6*/# #.. ./-/ 03*2)/-+'6;2) $&'5+'$)'' 3*'20*)>; /6+$'#-/-$.0.)"$3+-0'5(+'.; ?#$./-).'0*)!)''6''*4. )"'$.#A.+&$)"2$). ?-62.2'*-'2+'6-.).2'+'6-.'**&$)"*- /*,2$)//#(.'3.4$/#/#-'$(7*4$/.#;@ 4''A5+'$))*(+'/*+)$)"-+-/*$-;@ Jeremy Silman, author of ‘How to Reassess Your Chess’ Uwe Bekemann, German Correspondence Chess NEW! Strategic Chess Exercises The Art of the Tarrasch Defence NEW! Find the Right Way to Outplay Your Opponent Strategies, Techniques and Surprising Ideas Emmanuel Bricard HHJ+".AEHJ;OK Alexey Bezgodov IHF+".AEHM;OK $)''6)5-$..**&/#/$.)*/*2//0.; -2''6 ?"*'($)*-.*2-C<D-$''$)/'64-$1);@ -

Farmers Join Push to Rezone Prime Land

THE TWEED SHIRE Volume 1 #1 Thursday, August 28, 2008 Advertising and news enquiries: Phone: (02) 6672 2280 Fax: (02) 6672 4933 [email protected] [email protected] www.tweedecho.com.au LOCAL & INDEPENDENT Farmers join New kids on push to rezone the block prime land Ken Sapwell ture zoning hit a major hurdle when the land was recently given the State’s A strong push is again underway to highest possible classifi cation. turn rich farming land at Cudgen into Their change of heart comes as an urban landscape – and for the fi rst property investors and land specula- time the plateau’s red-soil farmers are tors continue to risk huge stakes in lending their weight. a rezoning gamble, including a $4.5 Several families who’ve farmed the million Coles joint venture deal for a Tweed’s salad bowl for generations are Lynne Beck family property, with an among 26 landholders signing a peti- extra $5 million if it can be used for a tion calling on the council and NSW supermarket and town houses. Planning Minister Frank Sartor to Warren Polglase, who is seeking rezone the land for urban purposes. to regain the mayoral robes, says as a Th e petition asks Mr Sartor to ar- former wheat and rice grower he well range a meeting to discuss an urgent understood the farmers’ situation. review of Cudgen’s State Signifi cance He says their request is a ‘fair ask status, citing changes since 2005 which and worthy of serious consideration’ Spring has sprung throughout the Tweed, and with it comes new births, not least the Tweed Shire Echo’s. -

India Chess Federation (AICF) Opposite Party Through Its Secretary Hall No.82, Jawahar Lal Nehru Stadium Chennai, Tamil Nadu

COMPETITION COMMISSION OF INDIA Case No. 79 of 2011 In Re: Hemant Sharma Informant No. 1 240, Bashiratganj Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh Devendra Bajpai Informant No. 2 5/588, Vikas Nagar Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh Gurpreet Pal Singh Informant No. 3 6E, Matasundari Place DDU Marg, New Delhi Karun Duggal Informant No. 4 30-A, Kewal Park Extension Opposite Metro Pillar 72, Azadpur Delhi And All India Chess Federation (AICF) Opposite Party Through its Secretary Hall No.82, Jawahar Lal Nehru Stadium Chennai, Tamil Nadu Case No. 79 of 2011 Page 1 of 45 CORAM Mr. Devender Kumar Sikri Chairperson Mr. Sudhir Mital Member Mr. Augustine Peter Member Mr. U. C. Nahta Member Mr. Justice G.P. Mittal Member Appearances during the final hearing held on 21st February, 2018 For the Informant : Ms. Shivani Lakhanpal, Advocate Informant-in-person For the Opposite Party : Mr. J. Sivanandaraaj, Advocate Ms. Shalini Kaul, Advocate Ms. Ridhima Sharma, Advocate Order under Section 27 of the Competition Act, 2002 A. Background 1. The present information has been filed under Section 19(1)(a) of the Competition Act, 2002 (the ‘Act’) by Mr. Hemant Sharma (‘Informant No.1’), Mr. Devendra Bajpai (‘Informant No.2’), Mr. Gurpreet Pal Singh (‘Informant No.3’) and Mr. Karun Duggal (‘Informant No.4’) (All collectively referred to as the ‘Informants’) against All India Chess Federation (the ‘OP’/‘AICF’), alleging, inter-alia, contravention of the provisions of Sections 3 and 4 of the Act. Case No. 79 of 2011 Page 2 of 45 2. The information was filed by the Informants pursuant to the directions of the Hon’ble Delhi High Court in Writ Petition (Civil) No.5770 of 2011, contesting certain conduct and practices of AICF. -

Current Affairs April 2016

CCUURRRREENNTT AAFFFFAAIIRRSS AAPPRRIILL 22001166 -- AAWWAARRDDSS http://www.tutorialspoint.com/current_affairs_april_2016/awards.htm Copyright © tutorialspoint.com News 1 - Jailed Egyptian author-journalist Ahmed Naji to receive the PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award Imprisoned Egyptian author and journalist, Ahmed Naji, is being awarded the PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award, presented by PEN America at Pen America's annual Literary Gala on 16 May 2016 at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Harry Potter creator, J.K. Rowling will be honoured with the 2016 PEN/Allen Foundation Literary Service Award for engendering a love of literature among children worldwide. Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha and LeeAnne Walters will accept the 2016 PEN/Toni and James C. Goodale Freedom of Expression Courage Award for their brave efforts to expose the water crisis in Flint, Michigan. Additionally, the gala will applaud its Publisher Honoree, Hachette Book Group CEO Michael Pietsch, for his leadership in the fight against censorship. News 2 - Ranveer Singh honoured as 'Maharashtrian of The Year' Actor Ranveer Singh will be honoured as ‘Maharashtrian of The Year’ for his role of Maratha warrior Peshwa Bajirao II in “Bajirao Mastani”. The award is given to those individuals who have positively influenced the Brand Maharashtra. The jury members to choose the awardee for this year included former Union Home Minister Sushil Kumar Shinde, Former Union Minister Praful Patel, eminent lawyer Ujjwal Nikam, social activist Medha Patkar, businessman Harsh Goenka, veteran journalist Ayaz Memon, filmmaker Madhur Bhandarkar and others. News 3 - PM Modi conferred Saudi Arabia’s highest civilian award Prime Minister Narendra Modi was conferred the King Abdulaziz Sash honor – the highest civilian honor of Saudi Arabia by King Salman bin Abdulaziz at the Royal Court, Riyadh. -

Texas Knights

TEXAS KNIGHTS The official publication of the Texas Chess Association Volume 56, Number 2 P.O. Box 151804, Ft. Worth, TX 76108 Nov.-Dec. 2014 Happy Holidays! Table of Contents From the Desk of the TCA President .................................................................................................................. 4 Spotlight On… WFM Emily Nguyen .................................................................................................................... 5 World Chess Championship 2014 ..................................................................................................................... 6 Leader List ....................................................................................................................................................... 16 18th Annual Texas Grade and Collegiate Championships ................................................................................. 18 Touch and Move! By WCM Claudia Muñoz ...................................................................................................... 24 Led by the Blind by Robert L. Myers ................................................................................................................ 26 Tactics Time! by Tim Brennan (answers on page 29) ................................................................................ 28 Upcoming Events............................................................................................................................................. 30 facebook.com/TexasChess texaschess.org