UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Regional Project/Programme

REGIONAL PROJECT/PROGRAMME PROPOSAL PART I: PROJECT/PROGRAMME INFORMATION Climate change adaptation in vulnerable coastal cities and ecosystems of the Uruguay River. Countries: Argentina Republic and Oriental Republic of Uruguay Thematic Focal Area1: Disaster risk reduction and early warning systems Type of Implementing Entity: Regional Implementing Entity (RIE) Implementing Entity: CAF – Corporación Andina de Fomento (Latin American Development Bank) Executing Entities: Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development of Argentina and Ministry of Housing, Land Planning and Environment of Uruguay. Amount of Financing 13.999.996 USD (in U.S Dollars Equivalent) Requested: 1 Project / Programme Background and Context: 1.1. Problem to be addressed – regional perspective 1. The Project’s implementation is focused on the lower Uruguay river´s littoral area, specifically in the vulnerable coastal cities and ecosystems in both Argentinean and Uruguayan territories. The lower Uruguay river´s littoral plays a main role being a structuring element for territorial balance since most cities and port-cities are located in it, with borther bridges between the two countries (Fray Bentos – Gualeguaychú; Paysandú – Colón; and Salto – Concordia). The basin of the Uruguay river occupies part of Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil, with a total area of approximately 339.000 Km2 and an average flow rate of 4.500 m3 s-1. It´s origin is located in Serra do Mar (Brazil), and runs for 1.800 Km until it reaches Río de la Plata. A 32% of its course flows through Brazilian territory, 38% forms the Brazil-Argentina boundary and a 30% forms the Argentina-Uruguay boundary. 2. The Project’s area topography is characterized by a homogeneous landform without high elevations, creating meandric waterways, making it highly vulnerable to floods as one of its main hydro-climatic threats, which has been exacerbated by the effects of climate change (CC). -

Argentina and Uruguay - the Martin Garcia Channel

ARGENTINA AND URUGUAY - THE MARTIN GARCIA CHANNEL Case Study (Transportation) Project Summary: The Rio de la Plata estuary is nestled between Uruguay, Argentina, and the Atlantic Ocean. It serves as the waterway access to Buenos Aires, as well as for the Uruguay and Paraná Rivers, the Paraná Interior, and the upstream Argentine grain ports of Rosario and Santa Fé. Within the Rio de la Plata estuary, the average depth is between one and six meters, except in the two channels: the artificial Mitre Channel, parallel to the Argentine coast and the natural Martin Garcia Channel, parallel to the Uruguayan coast. The Martin Garcia Channel is 106 kilometers long, beginning near the city of Colonia del Sacramento, Uruguay, and ending at the Uruguay River, near Nueva Palmira, Uruguay. Both channels have been sporadically dredged to various depths ever since the Martin Garcia Channel was first opened in 1892. Dredging of the waterways throughout the river basin has been an integral part of the MERCOSUR’s plan, the trade agreement between Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay signed in 1991. The objective was to make the transportation of goods more efficient and thereby improve the economy of the region. Increased shipping in the region and the need for a more efficient way to move bulk goods, requiring larger vessels, added strain to the existing channels. The Martin Garcia Channel, while more direct and a little deeper than the Mitre Channel, was not deep enough to handle the larger vessels that many shipping companies had begun to utilize, nor wide enough to accommodate multiple vessels concurrently. -

Río Negro – Uruguay)”

“Determinación de los niveles de concentración de elementos traza en las aguas subterráneas de los alrededores de la ciudad de Young (Río Negro – Uruguay)” DETERMINACIÓN DE LOS NIVELES DE CONCENTRACIÓN DE ELEMENTOS TRAZA EN LAS AGUAS SUBTERRÁNEAS DE LOS ALREDEDORES DE LA CIUDAD DE YOUNG (RÍO NEGRO – URUGUAY) NATALIA CABRERA LABORDE TUTORA: DRA. ELENA PEEL CO-TUTORA: LIC. XIMENA LACUÉS TRABAJO FINAL LICENCIATURA EN GEOLOGÍA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS – UDELAR 2020 Natalia Cabrera Laborde 1 “Determinación de los niveles de concentración de elementos traza en las aguas subterráneas de los alrededores de la ciudad de Young (Río Negro – Uruguay)” Agradecimientos A mi tutora Dra. Elena Peel y co-tutora Lic. Ximena Lacués por el apoyo, la paciencia, por los consejos brindados y por ayudarme a materializar las ideas de modo de darle forma a este trabajo y hacer posible que saliera adelante. A A. Manganelli y R. Carrión que de manera desinteresada escucharon mis dudas, me aconsejaron y mostraron mis errores para así modificarlos. A Esteban Abelenda, Valentina Ribero y Hugo Bonjour, mi grupo de estudio, con los que vivimos días de locura, nervios, estrés, cansancio pero también días muy divertidos e inolvidables. A las instituciones estatales (OSE, DINAGUA, DINAMIGE) por proporcionarme los datos de sus pozos y, a los ciudadanos, empresas e industrias de Young que muy amablemente accedieron a permitirme sacar muestras y a realizar medidas de sus perforaciones. Información necesaria para la realización de este trabajo. Y por último y no por ello menos importante, a mi familia, a mi esposo Juan Pablo, a Fede, a Agus que viene en camino, y a mis amigas/os que de una u otra forma estuvieron ahí, aguantando plantones, ayudando y alentándome para finalizar esta tesis. -

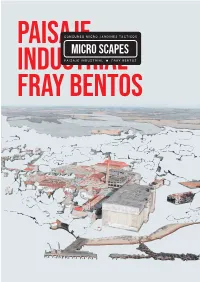

Bando Fray Bentos 220120

PAISAJECONCURSO MICRO JARDINES TACTICOS micro scapes INDUSTRIALPAISAJE INDUSTRIAL FRAY BENTOS FRAY BENTOS 02 Micro Jardines Tácticos es un concurso internacional de arquitectura, arte, diseño, y paisaje promovido por el Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo y la Intendencia Departamental de Rio Negro en el contexto del Paisaje Industrial Fray Bentos, declarado Los siguientes párrafos son basados en la segunda parte del ensayo mencionado antes y Patrimonio de la Humanidad en 2015. El objetivo en los objetivos del Plan Estratégico Fray del concurso Micro Jardines Tácticos es Bentos, aprobado en 2019: http://planestrategicofraybentos.com/ La ciudad de Fray Bentos se encuentra actualmente en un proceso de transformación dinamizar un espacio abierto dentro del núcleo derivado de dos hitos fundamentales en su historia reciente. Por un lado, la declaración del Exfrigorífico Anglo y su entorno como Patrimonio de la Humanidad de la UNESCO fabril del Exfrigorífico Anglo, potenciando su bajo el rubro Paisaje Industrial en 2015. Por otro, la re-funcionalización de esta misma área industrial como Polo Tecnológico Educativo a través de la instalación de diversos organismos de educación superior e investigación de ámbito nacional. Ambas valor histórico, cultural y turístico. La premisa circunstancias representan un nuevo escenario para la ciudad, con nuevas problemáticas y demandas de servicio asociadas, que previsiblemente se verán que funda esta iniciativa es el deseo de acompañadas de un incremento en el número de residentes y visitantes. complementar el proceso de recuperación y En 2017, la Intendencia de Río Negro (IRN), con el apoyo del Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo han gestionado la elaboración de un “Plan Estratégico y de Gestión de la valorización del Paisaje Industrial Fray Bentos ciudad de Fray Bentos – Exfrigorífico Anglo Patrimonio de la Humanidad”. -

Cumulative Impact Study Uruguay Pulp Mills

Cumulative Impact Study Uruguay Pulp Mills September 2006 Prepared by: In association with: CUMULATIVE IMPACT STUDY – URUGUAY PULP MILLS Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREAMBLE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ES.i 1.0 INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................1.1 1.1 Locations and Setting...........................................................................................1.2 1.2 Overview of the Projects ......................................................................................1.3 1.3 Economic Development.......................................................................................1.4 1.4 Regulatory Context..............................................................................................1.5 1.5 Opposition to the Pulp Mills..................................................................................1.6 1.6 The Cumulative Impact Assessment....................................................................1.7 1.7 Project Team........................................................................................................1.9 1.8 Cross Reference to the Hatfield Report ...............................................................1.9 2.0 PROJECT DESCRIPTIONS ................................................................................2.1 2.1 Wood Supply........................................................................................................2.2 2.2 Project Features...................................................................................................2.6 -

Extended Abstract

Cuadernos de Turismo, nº 45, (2020); pp. 561-565 Universidad de Murcia ISSN: 1139-7861 eISSN: 1989-4635 EXTENDED ABSTRACT TOURISM FROM ARGENTINA IN URUGUAY: A QUANTITATIVE BEHAVIORAL ANALYSIS Eva Martín Roda Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia. UNED [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9333-4832 Silvana Sassano Luiz Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia. UNED [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4030-3922 1. INTRODUCTION This article is a quantitative study about the importance and characteristics of the tou- rists coming from Argentina to Uruguay. Uruguay is one of the most important destinations for the Argentinians to spend their holidays. These flows of tourist have significant effects on the Uruguayan territory, economy and society. The coast of “El Rio de la Plata” is the more dynamic economic and demographic space, in both countries. The capital cities of these countries are both in the shore of “El Río de la Plata”, and there are a lot of common economics activities, encouraging the relationships between them. When studying the number of tourists arriving from any place of the world to Uru- guay, the largest group came from Argentine, according to data offered by the Ministry of Tourism of Uruguay. This is the reason why the objective of this article is to study the characteristics and behaviour of tourists arriving from Argentina to Uruguay. To carry out this study was used the information extracted out of the random surveys conducted by the Statistics Institute of Uruguay to abroad visitors entered the country. (INE 2018) 2. -

The Argentina-Uruguay Border Space: a Geographical Description

The Argentina-Uruguay Border Space: A Geographical Description El espacio fronterizo argentino-uruguayo: Una descripción geográf ica Alejandro Benedetti Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científ icas y Técnicas / Universidad de Buenos Aires [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper is part of a more extensive research project being carried out at the Institute of Geography of the University of Buenos Aires, whose purposes are 1) to describe and analyze the South American border spaces and 2) to understand what role they play in national territory-building. A geographical description of the Argentina-Uruguay border space will be presented, using a model that considers six components: territorial dif ferentiation, fron- tierization, subnational territory, supranational territory, border places, and mobility. The conclusions will show the main spatial continuities and discontinuities identif ied there. Keywords: 1. border space, 2. delimitation; 3. frontierization, 4. Argentina, 5. Uruguay. RESUMEN Este trabajo forma parte de una investigación más amplia que se está desarrollando en el Instituto de Geografía de la Universidad de Buenos Aires, la cual tiene como propósitos: 1) describir y analizar los espacios fronterizos interestatales sudamericanos, y 2) comprender su función en la construcción de los territorios nacionales. Aquí se presentará una descrip- ción geográf ica del espacio fronterizo argentino-uruguayo, siguiendo un modelo de análisis que considera seis componentes: diferenciación territorial, fronterización, territorios subna- cionales, territorios supranacionales, lugares de frontera y movilidades. En las conclusiones se expondrán las principales continuidades y discontinuidades espaciales allí identif icadas. Palabras clave: 1. espacio fronterizo, 2. delimitación, 3. fronterización, 4. Argentina, 5. Uruguay. Date of receipt: April 23, 2014. -

Free Zones: Exports of Goods

Sectorial report FREE ZONES: EXPORTS OF GOODS June 2020 Free Trade Zones play an important role in attracting investment, generating skilled employment and diversifying the country's exports. This report focuses on the importance of free zones in Uruguay's exports of goods, either by using them as logistics centers (they are intermediate destinations for exports of grains or certain pharmaceutical products) or also as industrial processing locations (cellulose and beverage concentrate). In 2019, Uruguay's total exports of goods were around US$ 9.1 billion. Of this total, approximately 31% was sent abroad from one of Uruguay's Free Trade Zones. On the other hand, sales of goods from Uruguay to the Free Trade Zones explained 17% of total exports in 2019, totaling US$ 1.3 billion. These mainly correspond to wood for Fray Bentos Free Zone and Punta Pereira Free Zone for cellulose production, and grain for Nueva Palmira Free Zone. The large investments that have been made in the Free Trade Zones - favored by the current regulatory framework - have been the driving force behind their development. Based on data from the Free Zone Area of the Ministry of Economy and Finance, the total accumulated investment exceeded US$ 7.1 billion between 2005 and 2018. In the last year, the total investment in Free Trade Zones was US$ 380 million. The Free Trade Zones also play an important role in the generation of highly skilled employment. They employ 15,337 people (not including non-dependents), according to MEF data. The total number of companies operating in Free Trade Zones is around 1,125. -

SNAP Estero Farrapos Lineas OT Microrregión

MINISTERIO ORGANISMO GOBIERNO AUTÓNOMO DE MEDIO AMBIENTE DE ESPAÑA PARQUES Y MEDIO RURAL Y MARINO NACIONALES CONSULTORÍA PARA EL PROYECTO DE REHABILITACIÓN DEL GALPÓN DE PIEDRA DE SAN JAVIER Y SU ÁREA DE INFLUENCIA Introducción y guía conceptual El trabajo de consultoría contratado requiere para este aspecto de la tarea la presentación de dos diferentes niveles de propuestas , una, de lineamientos de ordenamiento territorial abarcando la escala de la microrregión donde se ubica el Área Natural Protegida y la otra, comprendiendo sólo la calificación patrimonial a la escala del pueblo San Javier y su entorno inmediato. Conviene precisar al inicio, que la propuesta se apoya, en igual medida, en la clara explicitación de un modo de abordaje metodológico , al que se suma, la propia experiencia previa en la microrregión en actuaciones de ordenamiento territorial y patrimonio, que se referirán. En ese sentido, en primer término, bajo la forma de una síntesis conceptual breve , se presentan los principales criterios que explicitan el modo en que se desarrollará y las categorías de análisis que la componen. • La interpretación de la construcción histórica del territorio • El análisis morfológico como criterio de ordenación • Los recursos patrimoniales como base de desarrollo local • Las escalas de observación El Bajo Río Uruguay: Salto – Nueva Palmira / ambas márgenes La Micro Región: Paysandú + Colón Fray Bentos + Gualeguaychú Young Mercedes Hitos naturales y culturales El Pueblo San Javier La Villa Nuevo Berlín El Área Natural Protegida Estero -

Fray Bentos, 16 De Julio De 2007

JUNTA DEPARTAMENTAL DE RÍO NEGRO ACTA 116 PRESIDE LA SEÑORA EDILA IRMA LUST Presidenta Sesión ordinaria de fecha 24 de mayo de 2019 ACTA 116 En la ciudad de Fray Bentos, el día 24 de mayo del año 2019, siendo la hora 20:00, celebra reunión ordinaria la Junta Departamental de Río Negro. TEXTO DE LA CITACIÓN: «La Junta Departamental de Río Negro se reúne el día viernes 24 de mayo de 2019, a la hora 20:00, en sesión ordinaria, a efectos de considerar lo siguiente: 1. Aprobación de Actas 114 y 115 de fechas 26/4/19 y 10/5/19 respectivamente. 2. Media Hora Previa. 3. Asuntos Entrados. ORDEN DEL DÍA 1. Señor Edil Washington Laco. Solicitud de ayuda al Ejecutivo Departamental para realizar mejoras edilicias en local perteneciente a Cruz Roja San Javier. (Carp. 1, Exp. 4297). 2. Informe de la Comisión de Legislación. Elaboración de Ordenanza que esté en consonancia y coincidencia con la Ley 17515 de regulación del ejercicio del trabajo sexual. (Repartido 605). 3. Informe de la Comisión de Legislación. Modificación artículo 18° de Ordenanza de Servicio de Remises. (Repartido 606). 4. Informe de la Comisión de Legislación. Inquietudes del señor Antonio Russo relacionadas con el tema “chapa remise”. (Repartido 607). 5. Informe de la Comisión de Legislación. Propuesta de modificación de Ordenanza de Transporte Turístico. (Repartido 608). 6. Informe de la Comisión de Legislación (en mayoría). Propuesta de modificación del artículo 3° de la Ordenanza de Taxis. (Repartido 609). 7. Informe de la Comisión de Legislación (en mayoría). Propuesta de modificación del artículo 2° de la Ordenanza de Servicio de Remises. -

Catia Casternov Una Mirada a La Historia De San Javier

FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES TALLER DE CULTURA CATIA CASTERNOV UNA MIRADA A LA HISTORIA DE SAN JAVIER Gabriela Ugo CI: 2.905.976-1 Ximena Vargas CI: 3.570.213-6 Ana Zapater CI: 4.077.727-1 1 Fue en nuestra segunda visita a San Javier que conocimos a la protagonista de nuestra historia de vida. Era un sábado de mañana bien temprano, el pueblo dormía, no había nadie por las calles solo los pájaros rompían el silencio. Llegamos al único sitio que encontramos abierto el bar de Elsa, con ella charlamos sobre los motivos de nuestra visita, le manifestamos nuestro interés por conocer la historia de San Javier y de los primeros inmigrantes rusos que vinieron al Uruguay, enseguida surgió el nombre de Catia, “ella recibe a los que vienen de afuera y quieren saber sobre San Javier, es la biznieta de Basilio Lubkov fundador del pueblo”, afirmó. Consideramos la posibilidad de entrevistarnos con ella, ya que según lo que nos había comentado Elsa era una persona abierta, dispuesta al dialogo con foráneos como nosotras y con una historia que contar, al ser su familia y más concretamente su bisabuelo un personaje clave en la historia del pueblo. Localizarla no fue difícil, casi todos en San Javier la conocen y esa misma mañana nos encontramos con ella. Ana Catalina Casternov Michin -Catia- nació un 23 de diciembre de 1938 en el pueblo de San Javier, departamento de Río Negro. Es la menor de tres hermanas, sus padres son de origen ruso, ambos eran muy pequeños cuando emprendieron el viaje al Uruguay junto a 300 familias mas en el año 1913, conformando así la primer oleada migratoria de rusos al país. -

Periplo De Los Soles 06 Nights

Periplo de los Soles 06 Nights Day 1 - Colonia Arrive to Colonia del Sacramento port, where you will pick the previously chosen rented car. Check in at Real Colonia Hotel. Accommodation is for 2 nights with breakfast included. You will have the rest of the day at your leisure for resting or walking around. Day 2 - Colonia COLONIA DEL SACRAMENTO is located on the East bank of the Río de la Plata, (180km west of Montevideo, and only 50km from Buenos Aires by ferry). It is an irresistibly picturesque town enshrined as a UNESCO World Heritage site. Its Historic Quarter, an irregular colonial area of narrow cobbled stone streets, occupies a small peninsula jutting into the river. The riverfront provides a venue for spectacular sunsets. Founded in 1680 by Portugal, the colony was later disputed by the Spanish who had settled in Buenos Aires, at the opposite bank of the river. José de Garro conquered the colony in 1680, and returned to Portugal the following year. The Spanish conquered it again in March 1705 after a siege of five months, but gave it back in the Treaty of Utrecht. Another attack during the Spanish-Portuguese War, 1735-1737, failed. Between 1750 and 1777, it kept changing hands from crown to crown due to treaties, until it remained with the Spanish. It then transferred to Portuguese control again, being later incorporated into Brazil’s territory after 1816, when the entire territory of Uruguay was seized by Portugal and renamed the Cisplatina province. On January 10, 1809, before the independence of Uruguay, it was designated as a "Villa" (town) and has since been elevated to the category of "Ciudad" (city).