Enfield Archaeological Society Archive Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enfield Society News, 214, Summer 2019

N-o 214, Summer 2019 London Mayor voices concerns over Enfield’s proposals for the Green Belt in the new Local Plan John West ur lead article in the Spring Newsletter referred retention of the Green Belt is also to assist in urban to the Society’s views on the new Enfield Local regeneration by encouraging the recycling of derelict and Plan. The consultation period for the plan ended other urban land. The Mayor, in his draft new London in February and the Society submitted comments Plan has set out a strategy for London to meet its housing Orelating to the protection of the Green Belt, need within its boundaries without encroaching on the housing projections, the need for master planning large Green Belt”. sites and the need to develop a Pubs Protection Policy. Enfield’s Draft Local Plan suggested that Crews Hill was The Society worked closely with Enfield RoadWatch and a potential site for development. The Mayor’s the Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE) to observations note that, as well as the issue of the Green produce a document identifying all the potential Belt, limited public transport at Crews Hill with only 2 brownfield sites across the Borough. That document trains per hour and the limited bus service together with formed part of the Society’s submission. the distance from the nearest town centre at Enfield Town The Enfield Local plan has to be compatible with the mean that Crews Hill is not a sustainable location for Mayor’s London Plan. We were pleased to see that growth. -

Medieval Pottery from Romsey: an Overview

Proc. Hampshire Field Club Archaeol. Soc. 67 (pt. II), 2012, 323–346 (Hampshire Studies 2012) MEDIEVAL POTTERY FROM ROMSEY: AN OVERVIEW By BEN JERVIS ABSTRACT is evidence of both prehistoric and Roman occupation, but this paper will deal only with This paper summarises the medieval pottery recovered the medieval archaeology, from the mid-Saxon from excavations undertaken by Test Valley Archae- period to the 16th century. ological Trust in Romsey, Hampshire from the Several excavations took place between the 1970’s–1990’s. A brief synthesis of the archaeology of 1970’s–90’s in the precinct of Romsey Abbey Romsey is presented followed by a dated catalogue of (see Scott 1996). It has been suggested on the pottery types identified, including discussions of the basis of historical evidence and a series fabric, form and wider affinities. The paper concludes of excavated, early, graves that the late Saxon with discussions of the supply of pottery to Romsey in abbey was built on the site of an existing eccle- the medieval period and also considers ceramic use siastical establishment, possibly a minster in the town. church (Collier 1990, 45; Scott 1996, 7). The foundation of the nunnery itself can be dated to the 10th century (Scott 1996, 158), but it INTRODUCTION was evacuated in AD 1001, due to the threat of Danish attack, being re-founded later in The small town of Romsey has been the focus the 11th century. The abbey expanded during of much archaeological excavation over the last the Norman period, with the building of the 30–40 years, but very little has been published choir and nave (Scott 1996, 7). -

Bulletin N U M B E R 3 2 0 May/June 1998

Registered Charity No: 272098 ISSN 0585-9980 SURREY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY CASTLE ARCH, GUILDFORD GU1 3SX Tel/Fax: 01483 532454 E-mail: [email protected] Bulletin N u m b e r 3 2 0 May/June 1998 BRONZE AGE HUT FOUND AT LALEHAM Post-built round house, looking north-west through its entrance. Preliminary work on the finds suggest a date in the late 2nd millennium BC. Ranging Rods marl<ed in 0.20m divisions, but ttie director, Graham t-iayman, provides a human scale whilst demonstrating his understanding of contemporary folk-dancing. Excavations at Home Farm, Laleham in 1997 Graham Hayman In May and June of last year the Surrey County Archaeological Unit undertook excavations at Home Farm, Laleham, for Greenham Construction Materials Ltd, as part of an archaeological scheme of work approved to comply with the conditions of a Planning Permission for the extraction of gravel. Home Farm Quarry Is being worked In phases over several years, with each phase area being restored to Its agricultural purposes once quarrying Is completed. Work in 1997 was in the Phase 6 area and proceeded as a result of discoveries made during an evaluation by trenching in March 1997. Five areas A to E were excavated. Areas A to C in the south revealed occasional small pits and post-holes, two large water-holes, various ditches, and at least two cremation burials. Most features were sparsely distributed, however, with no significant concentrations; and produced only a few pot sherds and/or pieces of struck flint. Such a paucity of finds made it difficult to date some features, but a provisional assessment is that most were of Bronze Age date, some may be Neolithic, and at least one ditch was probably Roman. -

Foodbank in Demand As Pandemic Continues

ENFIELD DISPATCH No. 27 THE BOROUGH’S FREE COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER DEC 2020 FEATURES A homelessness charity is seeking both volunteers and donations P . 5 NEWS Two new schools and hundreds of homes get go-ahead for hospital site P . 6 ARTS & CULTURE Enfield secondary school teacher turns filmmaker to highlight knife crime P . 12 SPORT How Enfield Town FC are managing through lockdown P . 15 ENFIELD CHASE Restoration Project was officially launched last month with the first of many volunteering days being held near Botany Bay. The project, a partnership between environmental charity Thames 21 and Enfield Council, aims to plant 100,000 trees on green belt land in the borough over the next two years – the largest single tree-planting project in London. A M E E Become a Mmember of Enfield M Dispatch and get O the paper delivered to B your door each month E Foodbank in demand C – find out more R E on Page 16 as pandemic continues B The Dispatch is free but, as a Enfield North Foodbank prepares for Christmas surge not-for-profit, we need your support to stay that way. To BY JAMES CRACKNELL we have seen people come together tial peak in spring demand was Citizens Advice, a local GP or make a one-off donation to as a community,” said Kerry. “It is three times higher. social worker. Of those people our publisher Social Spider CIC, scan this QR code with your he manager of the bor- wonderful to see people stepping “I think we are likely to see referred to North Enfield Food- PayPal app: ough’s biggest foodbank in to volunteer – we have had hun- another big increase [in demand] bank this year, most have been has thanked residents dreds of people helping us. -

Buses from Enfield Retail Park

��ses f�o� Enfield Retail �ark 217 317 from stops C, D, E, Q from stops C, D, E, M, N, P, Q 121 towards Enfield Island Village Waltham Cross Bus Station from stops M, N, Q, R, S Ordnance Road Turkey Street Hertford Road 121 Albany Leisure Centre Eastfields Road Hertford Road 191 Bell Lane Bullsmoor Lane Brimsdown 217 317 Hertford Road Avenue Great Cambridge Road Ingersoll Road Manor Court ENFIELD Turkey Street Great Cambridge Road HIGHWAY Hertford Road Durants School Great Cambridge Road 121 191 313 Enfield Crematorium towards Potters Bar / 191 Potters Bar Dame Alice Owen’s School Sch Great Cambridge Road Hoe Lane Hertford Road Oatlands Road from stops H, J, K, L, T from stops H, J, K, L, T Myddelton Avenue Great Cambridge Road Lancaster Road Forty Hill Carterhatch Lane 307 Baker Street Carterhatch 191 191 from stops M, N, Q, R, S Chase Farm Kenilworth Crescent Lane Hospital Brimsdown Great Cambridge Road Hertford Road Cambridge Gardens Carterhatch Lane Hunters Way 191 Harefield Close Green Street D R 307 H T D I A Enfield 317 M L Hertford Road O S L Enfield I Retail R Green Street 313 from stops F, G, H, J, K, L Y E E D �la�ing �ields M �a�� A K V L I Enfield Town F L R 121 Chase Side A Little Park Gardens D CROWN H 307 C 231 �o�t����� RO Enfield �eis��e D AD from Cent�e Enfield College The Ridgeway Town S stops B K M ET E M T A Y A �ains�����s 121 J, K, L E G I H D R S D O R I A B A O Oakwood D D 307 F �ings�ead R L O DEA O O RS LEY C ���ool B S R C Alexandra Road T C O UT �ala �ingo R H O N M E H AD BU R Durants Road Enfield Slades Enfield Enfield -

Further Draft Recommendations for New Electoral Arrangements in the West Area of Enfield Council

Further draft recommendations for new electoral arrangements in the west area of Enfield Council Electoral review October 2019 Translations and other formats: To get this report in another language or in a large-print or Braille version, please contact the Local Government Boundary Commission for England at: Tel: 0330 500 1525 Email: [email protected] Licencing: The mapping in this report is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. Licence Number: GD 100049926 2019 A note on our mapping: The maps shown in this report are for illustrative purposes only. Whilst best efforts have been made by our staff to ensure that the maps included in this report are representative of the boundaries described by the text, there may be slight variations between these maps and the large PDF map that accompanies this report, or the digital mapping supplied on our consultation portal. This is due to the way in which the final mapped products are produced. The reader should therefore refer to either the large PDF supplied with this report or the digital mapping for the true likeness of the boundaries intended. The boundaries as shown on either the large PDF map or the digital mapping should always appear identical. Contents Analysis and further draft recommendations in the west of Enfield 1 North and central Enfield 2 Southgate and Cockfosters 11 Have your say 21 Equalities 25 Appendix A 27 Further draft recommendations for the west area of Enfield. -

Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd

T H A M E S V A L L E Y ARCHAEOLOGICAL S E R V I C E S 14–16 Milkingpen Lane, Old Basing, Basingstoke, Hampshire An Archaeological Watching Brief by Jennifer Lowe and Sean Wallis Site Code: MLB06/65 (SU 6675 5302) 14-16 Milkingpen Lane, Old Basing, Basingstoke, Hampshire An Archaeological Watching Brief For Dr Weaver & Partners by Jennifer Lowe and Sean Wallis Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd Site Code MLB 06/65 December 2006 Summary Site name: 14-16 Milkingpen Lane, Old Basing, Basingstoke, Hampshire Grid reference: SU6675 5302 Site activity: Watching Brief Date and duration of project: 19th July – 21st August 2006 Project manager: Steve Ford Site supervisor: Jennifer Lowe and Sean Wallis Site code: MLB06/65 Area of site: 2688 sq m Summary of results: The watching brief revealed a moderate quantity of archaeological features including ditches, gullies, several pits and a square structure. The majority of features encountered suggested activity on the site during the 13th century with later activity, mid 16th-17th century, in the form of a ditch. Three sherds of residual Romano-British pottery were also recovered during the course of the works. Monuments identified: Medieval pits, ditches, square structure. Post-medieval ditch. Location and reference of archive: The archive is presently held at Thames Valley Archaeological Services, Reading and will be deposited Hampshire Museum Service in due course. This report may be copied for bona fide research or planning purposes without the explicit permission of the copyright holder Report edited/checked by: Steve Ford 21.12.06 Steve Preston 21.12.06 i Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd, 47–49 De Beauvoir Road, Reading RG1 5NR Tel. -

2012 Greenway Report

MUNICIPAL YEAR 2011/2012 REPORT NO. ACTION TO BE TAKEN UNDER Agenda – Part: 1 KD Num: NA DELEGATED AUTHORITY Subject: Enfield Greenways - Proposed Path through PORTFOLIO DECISION OF: Hilly Fields Park Cabinet Member for Environment REPORT OF: Wards: Chase Director - Environment Contact officer and telephone number: Jonathan Goodson 020 8379 3474 Email: [email protected] 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 This report presents proposals to provide new or upgraded paths in Hilly Fields Park to create an east-west route through the parkland. This would be a shared facility for pedestrians, cyclists and wheelchair users. The drawing in Appendix A shows the route proposed during the consultation exercise. 1.2 The Forty Hall section forms part of a wider route between Hadley Wood and Enfield Island Village. The drawing in Appendix B shows the full route as currently proposed. The section between the A10 and Enfield Island Village is largely complete. 1.3 Minor highway improvements to aid crossing movements of Clay Hill near the Rose & Crown public house are also proposed. 1.4 The cost of implementing this facility is estimated to be £200,000. This is being met by the Corridors, Neighbourhoods and Supporting Measures 2012/13 budget. 2. RECOMMENDATIONS To approve the implementation of the amended route shown in Appendix F for construction in summer 2012. This differs from the former proposals as follows: Route north of the brook to follow the existing path past the football pitch rather than following the path shown through the woodland. All new and widened paths to be constructed in hoggin or similar self-binding gravel surfacing. -

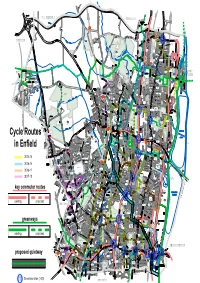

Cycle Routes in Enfield

9'.9;0*#6(+'.& $41:$1740' CREWS HILL Holmesdale Tunnel Open Space Crews Hill Whitewebbs Museum Golf Course of Transport Capel Manor Institute of Lea Valley Lea Valley Horticulture and Field Studies *'465/'4' Sports Centre High School 20 FREEZYWATER Painters Lane Whitewebbs Park Open Space Aylands Capel Manor Primary School Open Space Honilands Primary School Bulls Cross Field Whitewebbs Park Golf Course Keys Meadow School Warwick Fields Open Space Myddelton House and Gardens Elsinge St John's Jubilee C of E Primary School Freezywaters St Georges Park Aylands C of E Primary School TURKEY School ENFIELD STREET LOCK St Ignatius College RC School Forty Hall The Dell Epping Forest 0%4 ENFIELD LOCK Hadley Wood Chesterfield Soham Road Forty Hill Primary School Recreation Ground '22+0) Open Space C of E Primary School 1 Forty Hall Museum (14'56 Prince of Wales Primary School HADLEY Hadley Wood Hilly Fields Gough Park WOOD Primary School Park Hoe Lane Albany Leisure Centre Wocesters Open Space Albany Park Primary School Prince of Oasis Academy North Enfield Hadley Wales Field Recreation Ground Ansells Eastfields Lavender Green Primary School St Michaels Primary School C of E Hadley Wood Primary School Durants Golf Course School Enfield County Lower School Trent Park Country Park GORDON HILL HADLEY WOOD Russet House School St George's Platts Road Field Open Space Chase Community School St Michaels Carterhatch Green Infant and Junior School Trent Park Covert Way Mansion Queen Elizabeth David Lloyd Stadium Centre ENFIELD Field St George's C of E Primary School St James HIGHWAY St Andrew's C of E Primary School L.B. -

The First 50 Years – Part 2

No: 191 December 2008 Society News The Bulletin of the Enfield Archaeological Society 2 Forthcoming Events: EAS 16 January: Southgate before World War 1 13 February: Algeria: Nomads, Merchants and Oil Barons 13 March: Roman Enfield 17 April: Excavations & Fieldwork of EAS 2008 & AGM 3 Other Societies 4 Society Matters 5 Meeting Reports 19 October: London Cemeteries 6 Book Review: Middlesex Tales of Mystery and Murder 7 Will Shelton: The Highwayman of Maidens Bridge 8 Lower Palaeolithic Handaxe from Grange Park, Enfield 9 Fieldwork Report: Elsynge Palace 2008 12 Pastfinders News Society News is published quarterly in March, June, September and December The Editor is Jeremy Grove Background research ’all dull. See p. 7 for an account of one of Forty ’more colourful characters. http://www.enfarchsoc.org Meetings are held at Jubilee Hall, 2 Parsonage Lane, Enfield (near Chase Side) at 8pm. Tea and coffee are served and the sales and information table is open from 7.30pm. Visitors, who are asked to pay a small entrance fee of £1.00, are very welcome. If you would like to attend the EAS lectures, but find travelling difficult, please contact the Secretary, David Wills (Tel: 020 8364 5698) and we will do our best to put you in touch with another member who can give you a lift. The full lecture programme for 2008, organised by evidence, and recently published a paper on the subject Tim Harper, is as follows. You should also find a in a monograph on Roman London published in honour programme card enclosed with this newsletter. -

Surrey-Hampshire Border Ware Ceramics in Seventeenth-Century

SURREY-HAMPSHIRE BORDER WARE CERAMICS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH NORTH AMERICA by © Catherine Margaret Hawkins A Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Archaeology Memorial University of Newfoundland April 2016 St. John’s Newfoundland and Labrador Abstract During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Surrey-Hampshire Border ware ceramics were among of the most popular and widely used ceramics in southern England. This ceramic, produced along the Surrey-Hampshire border, was also shipped to English colonies in North America throughout the seventeenth century. This thesis will explore the types of vessels uncovered on archaeological sites in Newfoundland, New England and the Chesapeake, and examine the similarities and differences in the forms available to various colonists during this time period. By comparing the collections of Border ware found at various sites it is possible to not only determine what vessel forms are present in Northeastern English North America, but to determine the similarities and differences in vessels based on temporal, geographic, social or economic factors. A comparative study of Border ware also provides information on the socio- economic status of the colonists and on trading networks between England and North America during the seventeenth century. i Acknowledgements Grateful thanks are due first and foremost to my supervisor, Dr. Barry Gaulton, for everything he has done for me over the years. My interest in historical archaeology originated through working with Barry and Dr. Jim Tuck at Ferryland several years ago and I cannot thank him enough for his continued support, enthusiasm, advice and encouragement throughout the course of this research project. -

MEDIEVAL POTTERY RESEARCH GROUP Newsletter 74 November 2012 ______

MEDIEVAL POTTERY RESEARCH GROUP newsletter 74 November 2012 _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Secretary’s Notes Council met in September at the British Museum had held some very constructive discussions about the future directions which the group’s activities may take. Two topics dominated the agenda, the first of these was training. Alice Forward has undertaken some research into the kinds of specialist and non-specialist training currently available and which might be offered by the group in the future. We welcome any comments from members regarding the kinds of training which you would find useful and any comments on this subject should be addressed to the president. The second issue relates to the maintaining of standards, particularly within reports produced from developer-led projects. Central to this is co-operation with our Prehistoric and Roman colleagues in the production of joint standards, which can be easily disseminated to local authority curators. A need for non-specialist training into these standards was identified and we will be pursuing this with our colleagues within the curatorial sector going forward. In November members of the group came together with colleagues from the Association for the History of Glass at a conference held in honour of the late Sarah Jennings. Unfortunately I was unable to attend, but I hear from colleagues that this day was a great success and, more importantly, a fitting tribute to Sarah. Thanks are extended to Julie Edwards and Sarah Paynter for their hard work in organising the conference, and in pushing forward with plans for a festschrift in Sarah’s memory. Additionally, Chris Jarrett is continuing to work on a similar publication in honour of Anna Slowikowski.