The British Transatlantic Slave Trade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents Graphic—Description of a Slave Ship

1 Contents Graphic—Description of a Slave Ship .......................................................................................................... 2 One of the Oldest Institutions and a Permanent Stain on Human History .............................................................. 3 Hostages to America .............................................................................................................................. 4 Human Bondage in Colonial America .......................................................................................................... 5 American Revolution and Pre-Civil War Period Slavery ................................................................................... 6 Cultural Structure of Institutionalized Slavery................................................................................................ 8 Economics of Slavery and Distribution of the Enslaved in America ..................................................................... 10 “Slavery is the Great Test [] of Our Age and Nation” ....................................................................................... 11 Resistors ............................................................................................................................................ 12 Abolitionism ....................................................................................................................................... 14 Defenders of an Inhumane Institution ........................................................................................................ -

Texts Checklist, the Making of African American Identity

National Humanities Center Resource Toolbox The Making of African American Identity: Vol. I, 1500-1865 A collection of primary resources—historical documents, literary texts, and works of art—thematically organized with notes and discussion questions I. FREEDOM pages ____ 1 Senegal & Guinea 12 –Narrative of Ayuba Suleiman Diallo (Job ben Solomon) of Bondu, 1734, excerpts –Narrative of Abdul Rahman Ibrahima (“the Prince”), of Futa Jalon, 1828 ____ 2 Mali 4 –Narrative of Boyrereau Brinch (Jeffrey Brace) of Bow-woo, Niger River valley, 1810, excerpts ____ 3 Ghana 6 –Narrative of Broteer Furro (Venture Smith) of Dukandarra, 1798, excerpts ____ 4 Benin 11 –Narrative of Mahommah Gardo Baquaqua of Zoogoo, 1854, excerpts ____ 5 Nigeria 18 –Narrative of Olaudah Equiano of Essaka, Eboe, 1789, excerpts –Travel narrative of Robert Campbell to his “motherland,” 1859-1860, excerpts ____ 6 Capture 13 –Capture in west Africa: selections from the 18th-20th-century narratives of former slaves –Slave mutinies, early 1700s, account by slaveship captain William Snelgrave FREEDOM: Total Pages 64 II. ENSLAVEMENT pages ____ 1 An Enslaved Person’s Life 36 –Photographs of enslaved African Americans, 1847-1863 –Jacob Stroyer, narrative, 1885, excerpts –Narratives (WPA) of Jenny Proctor, W. L. Bost, and Mary Reynolds, 1936-1938 ____ 2 Sale 15 –New Orleans slave market, description in Solomon Northup narrative, 1853 –Slave auctions, descriptions in 19th-century narratives of former slaves, 1840s –On being sold: selections from the 20th-century WPA narratives of former slaves, 1936-1938 ____ 3 Plantation 29 –Green Hill plantation, Virginia: photographs, 1960s –McGee plantation, Mississippi: description, ca. 1844, in narrative of Louis Hughes, 1897 –Williams plantation, Louisiana: description, ca. -

Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution

Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Collection of Essays Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Collection of Essays Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission Kentucky Heritage Council © Essays compiled by Alicestyne Turley, Director Underground Railroad Research Institute University of Louisville, Department of Pan African Studies for the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission, Frankfort, KY February 2010 Series Sponsors: Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Kentucky Historical Society Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission Kentucky Heritage Council Underground Railroad Research Institute Kentucky State Parks Centre College Georgetown College Lincoln Memorial University University of Louisville Department of Pan African Studies Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission The Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission (KALBC) was established by executive order in 2004 to organize and coordinate the state's commemorative activities in celebration of the 200th anniversary of the birth of President Abraham Lincoln. Its mission is to ensure that Lincoln's Kentucky story is an essential part of the national celebration, emphasizing Kentucky's contribution to his thoughts and ideals. The Commission also serves as coordinator of statewide efforts to convey Lincoln's Kentucky story and his legacy of freedom, democracy, and equal opportunity for all. Kentucky African American Heritage Commission [Enabling legislation KRS. 171.800] It is the mission of the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission to identify and promote awareness of significant African American history and influence upon the history and culture of Kentucky and to support and encourage the preservation of Kentucky African American heritage and historic sites. -

Solomon Northup and 12 Years a Slave

Solomon Northup and 12 Years a Slave How to analyze slave narratives. Who Was Solomon Northup? 1808: Born in Minerva, NewYork Son of former slave, Mintus Northup; Northup's mother is unknown. 1829: Married Anne Hampton, a free black woman. They had three children. Solomon was a farmer, a rafter on the Lake Champlain Canal, and a popular local fiddler. What Happened to Solomon Northup? Met two circus performers who said they needed a fiddler for engagements inWashington, D.C. Traveled south with the two men. Didn't tell his wife where he was going (she was out of town); he expected to be back by the time his family returned. Poisoned by the two men during an evening of social drinking inWashington, D.C. Became ill; he was taken to his room where the two men robbed him and took his free papers; he vaguely remembered the transfer from the hotel but passed out. What Happened…? • Awoke in chains in a "slave pen" in Washington, D.C., owned by infamous slave dealer, James Birch. (Note: A slave pen were where (Note:a slave pen was where slaves were warehoused before being transported to market) • Transported by sea with other slaves to the New Orleans slave market. • Sold first toWilliam Prince Ford, a cotton plantation owner. • Ford treated Northup with respect due to Northup's many skills, business acumen and initiative. • After six months Ford, needing money, sold Northup to Edwin Epps. Life on the Plantation Edwin Epps was Northup’s master for eight of his 12 years a slave. -

Trauma of Slavery: a Critical Study of the Roots by Alex Haley

Journal of Literature, Languages and Linguistics www.iiste.org ISSN 2422-8435 An International Peer-reviewed Journal DOI: 10.7176/JLLL Vol.57, 2019 Trauma of Slavery: A Critical Study of the Roots by Alex Haley Faiza Javed Dar M.Phil. (English Literature), Department of English Government College Woman University, Faisalabad. Pakistan Abstract Roots by Alex Haley is a critical analysis of the traumas of slavery experienced by the Africans. As an Afro- American writer, he gives voice to the issues like racism, subjugation, identity crises of the Blacks, but most of all the institution of slavery. Slavery has been an important phenomenon throughout history. Africa has been intimately connected with this history through Americans. Slavery in America began when the African slaves were brought to the North American colony of Jamestown, Virginia, in 1619, to aid in the production of such lucrative crops like tobacco and cotton. After the research of twelve years, Haley describes the experiences of Kunta Kinte before and after his enslavement, who is the great-great-grandfather of the writer. Roots is not just a saga of one Afro-American family, it is the symbolic saga of a people. The dehumanization process of slavery assaults the mind, body, and soul of African slaves. The purpose of this paper is to highlight and investigate the slow momentum of social reform for Blacks in the U.S.A. This will be qualitative research and critical race analysis will be applied as a tool to analyze the text under discussion. By using the theory of Derrick Bell the researcher will try to explore racism and black identity in this work. -

Triangular Trade and the Middle Passage

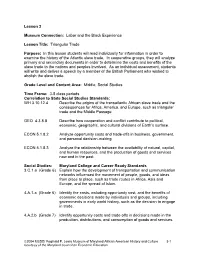

Lesson 3 Museum Connection: Labor and the Black Experience Lesson Title: Triangular Trade Purpose: In this lesson students will read individually for information in order to examine the history of the Atlantic slave trade. In cooperative groups, they will analyze primary and secondary documents in order to determine the costs and benefits of the slave trade to the nations and peoples involved. As an individual assessment, students will write and deliver a speech by a member of the British Parliament who wished to abolish the slave trade. Grade Level and Content Area: Middle, Social Studies Time Frame: 3-5 class periods Correlation to State Social Studies Standards: WH 3.10.12.4 Describe the origins of the transatlantic African slave trade and the consequences for Africa, America, and Europe, such as triangular trade and the Middle Passage. GEO 4.3.8.8 Describe how cooperation and conflict contribute to political, economic, geographic, and cultural divisions of Earth’s surface. ECON 5.1.8.2 Analyze opportunity costs and trade-offs in business, government, and personal decision-making. ECON 5.1.8.3 Analyze the relationship between the availability of natural, capital, and human resources, and the production of goods and services now and in the past. Social Studies: Maryland College and Career Ready Standards 3.C.1.a (Grade 6) Explain how the development of transportation and communication networks influenced the movement of people, goods, and ideas from place to place, such as trade routes in Africa, Asia and Europe, and the spread of Islam. 4.A.1.a (Grade 6) Identify the costs, including opportunity cost, and the benefits of economic decisions made by individuals and groups, including governments in early world history, such as the decision to engage in trade. -

1 Scene on Radio Made in America (Seeing White, Part 3) Transcript

Scene on Radio Made in America (Seeing White, Part 3) Transcript http://www.sceneonradio.org/episode-33-made-in-america-seeing-white-part-3/ [Gone with the Wind clip] Mammy: Oh naw, Miss Scarlett, come on, be good and eat just a little. Scarlett: No! I’m going to have a good time today. John Biewen: We Americans are notorious for not knowing or caring about history. It’s a generalization, forgive me, history buffs. But it’s a fair one, isn’t it? On the whole, Americans care a whole lot more about tomorrow. Forget yesterday. Yesterday was so long ago, for one thing. Get over it. [Roots clip] Kizzy, reading: For God giveth to a man who is good in his sight wisdom… [door opens] Master: Is that you reading, Kizzy? White woman, laughing: Uncle William, it was only a trick! John Biewen: That said, most of us do have a general picture in our minds of American slavery. Our schools teach it. And the Antebellum South has made recurring appearances in massively popular novels, movies, and TV series. [Roots clip] Father: But don’t split up the family, Master. You ain’t never been that kind of man. Please, Master! Master: Mr. Tom Moore owns Kizzy now. Mr. Odell will take her away today. [Kizzy crying] Mother: Oh God, my baby… 1 John Biewen: Some portrayals of American chattel slavery have been more unvarnished than others. [12 Years a Slave clip] Platt: But I’ve no understanding of the written text… Mistress Epps: Don’t trouble yourself with it. -

A Summary of Key Events in the Abolition of Slavery Worldwide by C.R

Black Freedom Days Fact Sheet - A Summary of Key Events in the Abolition of Slavery Worldwide by C.R. Gibbs, Historian of the African Diaspora January 1, 1804 Haiti celebrates independence. This country is the first modern nation to be led by a person of African descent. Haiti is the world’s only example of a successful slave revolt leading to the establishment of an internationally recognized nation or republic. Celebrations of Haiti’s existence and achievements take place throughout the Black Diaspora. September 15, 1829 Mexico abolishes slavery. March 25, 1807 The British Parliament passes the 1807 Abolition of Slave Trade Act to outlaw such trade throughout the British Empire. The Act prohibited British ships from being involved in the slave trade and marked the start of the end of the transatlantic traffic of human beings. A year later, the Royal Navy’s West African Squadron is established to suppress transatlantic slave trading. Over the next 60 years, the squadron’s anti-slavery operations along the West Coast of Africa and into East Africa and the Caribbean enforced the ban. William Wilberforce, the British Parliamentary leader of the anti-slavery movement, with key allies Thomas Clarkson, Olaudah Equiano and others, led the successful effort to convince the Parliament to pass the Act. The measure set in motion an international crusade that ultimately resulted in the outlawing of slavery worldwide. August 1, 1834 The 1833 Slavery Abolition Act takes effect to abolish slavery throughout the British Empire. At this time, the Empire spanned several continents and encompassed parts of the Caribbean, Africa, Canada, India, China, Australia, and South America as far as the tip of Argentina. -

An Error and an Evil: the Strange History of Implied Commerce Powers

American University Law Review Volume 68 Issue 3 Article 4 2019 An Error and an Evil: The Strange History of Implied Commerce Powers David S. Schwartz University of Wisconsin - Madison, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr Part of the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Schwartz, David S. (2019) "An Error and an Evil: The Strange History of Implied Commerce Powers," American University Law Review: Vol. 68 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr/vol68/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Error and an Evil: The Strange History of Implied Commerce Powers This article is available in American University Law Review: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr/vol68/ iss3/4 AN ERROR AND AN EVIL: THE STRANGE HISTORY OF IMPLIED COMMERCE POWERS DAVID S. SCHWARTZ* An underspecified doctrine of implied “reserved powers of the states” has been deployed through U.S. constitutional history to prevent the full application of McCulloch v. Maryland’s concept of implied powers to the enumerated powers—in particular, the Commerce Clause. The primary rationales for these implied limitations on implied federal powers stem from two eighteenth and nineteenth century elements of American constitutionalism. -

BLACK LONDON Life Before Emancipation

BLACK LONDON Life before Emancipation ^^^^k iff'/J9^l BHv^MMiai>'^ii,k'' 5-- d^fli BP* ^B Br mL ^^ " ^B H N^ ^1 J '' j^' • 1 • GRETCHEN HOLBROOK GERZINA BLACK LONDON Other books by the author Carrington: A Life BLACK LONDON Life before Emancipation Gretchen Gerzina dartmouth college library Hanover Dartmouth College Library https://www.dartmouth.edu/~library/digital/publishing/ © 1995 Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina All rights reserved First published in the United States in 1995 by Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey First published in Great Britain in 1995 by John Murray (Publishers) Ltd. The Library of Congress cataloged the paperback edition as: Gerzina, Gretchen. Black London: life before emancipation / Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index ISBN 0-8135-2259-5 (alk. paper) 1. Blacks—England—London—History—18th century. 2. Africans— England—London—History—18th century. 3. London (England)— History—18th century. I. title. DA676.9.B55G47 1995 305.896´0421´09033—dc20 95-33060 CIP To Pat Kaufman and John Stathatos Contents Illustrations ix Acknowledgements xi 1. Paupers and Princes: Repainting the Picture of Eighteenth-Century England 1 2. High Life below Stairs 29 3. What about Women? 68 4. Sharp and Mansfield: Slavery in the Courts 90 5. The Black Poor 133 6. The End of English Slavery 165 Notes 205 Bibliography 227 Index Illustrations (between pages 116 and 111) 1. 'Heyday! is this my daughter Anne'. S.H. Grimm, del. Pub lished 14 June 1771 in Drolleries, p. 6. Courtesy of the Print Collection, Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. 2. -

Pre-VFT, Domestic Slave Trade

A GUIDE TO YOUR VIRTUAL FIELD TRIP MUSEUM RESEARCH CENTER PUBLISHER ABOUT US The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center, and publisher dedicated to preserving the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. JENNY SCHWARTZBERG KENDRIC PERKINS RACHEL GAUDRY CURATOR OF EDUCATION EDUCATION SPECIALIST EDUCATION COORDINATOR Meet the educators! We will be your guides during the virtual field trip. YOUR FIELD TRIP JENNY WILL SHARE: • A tour of the virtual exhibition Purchased Lives: New Orleans and the Domestic Slave Trade • Highlights from the Works Progress Administration’s Slave Narrative Collection KENDRIC WILL SHARE: • A virtual walking tour exploring sites from the domestic slave trade in New Orleans • Stories of resistance from people who were enslaved • Information on the industries that fueled the domestic slave trade in America DURING THE FIELD TRIP, YOU CAN USE THE Q&A BOX TO ASK QUESTIONS AND MAKE COMMENTS. WE’D LOVE TO HEAR FROM YOU! ??? ??? SCROLL TO LEARN ABOUT THE KEY TERMINOLOGY THAT WILL BE USED IN OUR PRESENTATIONS. TRANSATLANTIC SLAVE TRADE 1619-1807 The transatlantic slave trade began in North America in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1619 with the arrival of the first slave ship bearing African captives. For nearly 200 years, this trade would continue. European nations would send manufactured goods to Africa and exchange these items for enslaved Africans. They would then send these people to the Americas to be sold. On the return voyages back to Europe, ships were filled with raw materials from the Americas. The transatlantic slave trade was outlawed by the US Congress on March 2, 1807. -

Roots- Teacher

RESEARCHING STUDENT RESEARCH GUIDE Roots is a historically accurate dramatization of the lives of enslaved people in the United States. It explores many themes related to American culture and society, freedom, and African heritage. Four of these big ideas, each aligned with one of the four Roots episodes, are listed in this activity guide. Use the episode summaries and resources to research one of these topics and compare different sources of information. As you gather facts, you’ll begin to develop your own perspectives about the subject. Build an argument about how you think the topic should be viewed and support it with evidence from your research. After your research, you’ll share your findings in a timeline, a paper, or a presentation. FACT-FINDING TOOLS Use the tools below to organize the information you uncover as well as your thoughts about the topic as you research. Tool 1—Glossary As you explore resources, build a glossary of terms whose definitions you are unclear about. To create your glossary, write down the term, then write your own definition using context clues before looking up the dictionary definition and incorporating it in your own sentence to confirm that you understand the word’s correct usage. Tool 2—Timeline On a separate sheet of paper, create a timeline of important facts related to your topic. This will help you create a historic record and make connections with current events. For each fact included on your timeline, identify the source and include a brief note about how the author presents the information. For example, consider each document’s titles, labels, tone, and headings.