A/Grca , Z<X)7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Juggle the Proof for Every Theorem an Exploration of the Mathematics Behind Juggling

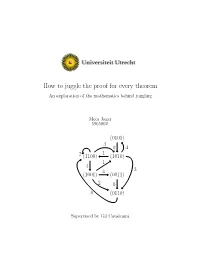

How to juggle the proof for every theorem An exploration of the mathematics behind juggling Mees Jager 5965802 (0101) 3 0 4 1 2 (1100) (1010) 1 4 4 3 (1001) (0011) 2 0 0 (0110) Supervised by Gil Cavalcanti Contents 1 Abstract 2 2 Preface 4 3 Preliminaries 5 3.1 Conventions and notation . .5 3.2 A mathematical description of juggling . .5 4 Practical problems with mathematical answers 9 4.1 When is a sequence jugglable? . .9 4.2 How many balls? . 13 5 Answers only generate more questions 21 5.1 Changing juggling sequences . 21 5.2 Constructing all sequences with the Permutation Test . 23 5.3 The converse to the average theorem . 25 6 Mathematical problems with mathematical answers 35 6.1 Scramblable and magic sequences . 35 6.2 Orbits . 39 6.3 How many patterns? . 43 6.3.1 Preliminaries and a strategy . 43 6.3.2 Computing N(b; p).................... 47 6.3.3 Filtering out redundancies . 52 7 State diagrams 54 7.1 What are they? . 54 7.2 Grounded or Excited? . 58 7.3 Transitions . 59 7.3.1 The superior approach . 59 7.3.2 There is a preference . 62 7.3.3 Finding transitions using the flattening algorithm . 64 7.3.4 Transitions of minimal length . 69 7.4 Counting states, arrows and patterns . 75 7.5 Prime patterns . 81 1 8 Sometimes we do not find the answers 86 8.1 The converse average theorem . 86 8.2 Magic sequence construction . 87 8.3 finding transitions with flattening algorithm . -

What's Happening at the IJA ?

THE INTERNATIONAL JUGGLERS’ ASSOCIATION October 2007 IJA e-newsletter editor: Don Lewis (email: [email protected]) Renew at http://www.juggle.org/renew What’s Happening at the IJA ? In This Issue: 2008 Lexington IJA Festival Help Wanted Have You Moved, or Gotten a New Email Address? Treasury Remember, the only way to ensure that you don't miss a World Juggling Day single issue of JUGGLE magazine is to give us your new Marketing the IJA address. The USPS will generally not forward JUGGLE Joggling Record magazine. Insurance To update your mailing address, email, or phone, please Regional Festivals send email to [email protected] or call TurboFest - Quebec City 415-596-3307 or write to: IJA, PO Box 7307, Austin, TX 78713-7307 USA. World Circus Year 2008 IJA Festival, Lexington, Kentucky The Hyatt is connected to the convention center. The convention center has a food court and shops and they are Lexington Notes by Richard Kennison open on a daily basis. There is a vibrant downtown area right Everyone, around the convention center. I just spent two days in Lexington, KY. I am very thrilled to tell The convention center contact person, the hotel contact person you that I think it is a wonderful site. I will not go into long and the theatre contact person are all professional and excited details here but: that we are coming. Bond Jacobs—the visitors bureau contact You can park your car (for free if you stay the the Hyatt) and person is an asset and will go the extra mile for us. -

The Coriolis Force and the Rattleback

The Coriolis Force and the Rattleback Frederick David Tombe, Belfast, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom, [email protected] 17th December 2010 Abstract. The rattleback (Celtic Stone) is the most mysterious phenomenon in classical mechanics. It reverses its angular momentum by inducing a Coriolis pressure from the dense background sea of rotating electron-positron dipoles which is the medium for the propagation of light. [1] Magnets and Rattlebacks I. Magnets and rattlebacks share in common the fact that they involve a mutual alignment of the spin moments of their constituent atoms and molecules. They differ however in that rattlebacks involve a rotation on the large scale in order to bring this alignment about. In magnetic materials, the induced spin alignment results in a linear force, whereas in rattlebacks, the induced spin alignment results in a reversal torque which opposes the initial rotation. Another important difference is that rattlebacks are generally made of materials which are not as dense as magnetic materials. [2] Gravity and Friction II. Gravity acts vertically downwards and so the reversal torque in a rattleback cannot be sourced in gravity. Sliding friction is involved in that it dissipates the entire motion, but sliding friction by its nature is not something that could cause a reversal torque. Static friction is necessary in order to enable the rocking stage of the rattleback’s cycle. Without static friction, a rattleback will not work. However, static friction by its nature is not something that could actually go as far as to cause a reversal torque. 1 Forging a Torque by Mathematical Manipulation III. -

Download (7MB)

Cairns, John William (1976) The strength of lapped joints in reinforced concrete columns. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/1472/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] THE STRENGTHOF LAPPEDJOINTS IN REINFORCEDCONCRETE COLUMNS by J. Cairns, B. Sc. A THESIS PRESENTEDFOR THE DEGREEOF DOCTOROF PHILOSOPHY Y4 THE UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW by JOHN CAIRNS, B. Sc. October, 1976 3 !ý I CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEIvIENTS 1 SUMMARY 2 NOTATION 4 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 7 Chapter 2 REVIEW OF LITERATURE 2.1 Bond s General 10 2.2 Anchorage Tests 12" 2.3 Tension Lapped Joints 17 2.4 Compression Lapped Joints 21 2.5 End Bearing 26 2.6 Current Codes of Practice 29 Chapter 3 THEORETICALSTUDY OF THE STRENGTHOF LAPPED JOINTS 3.1 Review of Theoretical Work on Bond Strength 32 3.2 Theoretical Studies of Ultimate Bond Strength 33 3.3 Theoretical Approach 42 3.4 End Bearing 48 3.5 Bond of Single Bars Surrounded by a Spiral 51 3.6 Lapped Joints 53 3.7 Variation of Steel Stress Through a Lapped Joint 59 3.8 Design of Experiments 65 Chapter 4 DESCRIPTION OF EXPERIMENTALWORK 4.1 General Description of Test Specimens 68 4.2 Materials 72 4.3 Fabrication of Test Specimens 78 4.4 Test Procedure 79 4.5 Instrumentation 80 4.6 Push-in Test Specimens 82 CONTENTScontd. -

Siteswap-Notes-Extended-Ltr 2014.Pages

Understanding Two-handed Siteswap http://kingstonjugglers.club/r/siteswap.pdf Greg Phillips, [email protected] Overview Alternating throws Siteswap is a set of notations for describing a key feature Many juggling patterns are based on alternating right- of juggling patterns: the order in which objects are hand and lef-hand throws. We describe these using thrown and re-thrown. For an object to be re-thrown asynchronous siteswap notation. later rather than earlier, it needs to be out of the hand longer. In regular toss juggling, more time out of the A1 The right and lef hands throw on alternate beats. hand means a higher throw. Any pattern with different throw heights is at least partly described by siteswap. Rules C2 and A1 together require that odd-numbered Siteswap can be used for any number of “hands”. In this throws end up in the opposite hand, while even guide we’ll consider only two-handed siteswap; numbers stay in the same hand. Here are a few however, everything here extends to siteswap with asynchronous siteswap examples: three, four or more hands with just minor tweaks. 3 a three-object cascade Core rules (for all patterns) 522 also a three-object cascade C1 Imagine a metronome ticking at some constant rate. 42 two juggled in one hand, a held object in the other Each tick is called a “beat.” 40 two juggled in one hand, the other hand empty C2 Indicate each thrown object by a number that tells 330 a three-object cascade with a hole (two objects) us how many beats later that object must be back in 71 a four-object asynchronous shower a hand and ready to re-throw. -

Understanding Siteswap Juggling Patterns a Guide for the Perplexed by Greg Phillips, [email protected]

Understanding Siteswap Juggling Patterns A guide for the perplexed by Greg Phillips, [email protected] Core rules (for all patterns) Synchronous siteswap (simultaneous throws) C1 We imagine a metronome ticking at some constant rate. Some juggling patterns involve both hands throwing at the Each tick is called a “beat.” same time. We describe these using synchronous siteswap. C2 We indicate each thrown object by a number that tells us how many beats later that object must be back in a hand S1 The right and left hands throw at the same time (which and ready to re-throw. counts as two throws) on every second beat. We group C3 We indicate a sequence of throws by a string of numbers the simultaneous throws in parentheses and separate the (plus punctuation and the letter x). We imagine these hands with commas. strings repeat indefinitely, making 531 equivalent to S2 We indicate throws that cross from hand to hand with an …531531531… So are 315 and 153 — can you see x (for ‘xing’). why? C4 The sum of all throw numbers in a siteswap string divided Rules C2 and S1 taken together demand that there be only by the number of throws in the string gives the number of even numbers in valid synchronous siteswaps. Can you see objects in the pattern. This must always be a whole why? The x notation of rule S2 is required to distinguish number. 531 is a three-ball pattern, since (5+3+1)/3 patterns like (4,4) (synchronous fountain) from (4x,4x) equals three; however, 532 cannot be juggled since (synchronous crossing). -

IJA Enewsletter Editor Don Lewis (Email: [email protected]) Renew at Http

THE INTERNATIONAL JUGGLERS! ASSOCIATION August 2011 IJA eNewsletter editor Don Lewis (email: [email protected]) Renew at http:www.juggle.org/renew IJA eNewsletter IJA Stage Championships Results, July 21 - 22, 2011 Individuals Contents: 1st: Tony Pezzo 2011 Championships Results 2nd: Kitamura Shintarou IJA Busking Competition 3rd: Tomohiro Kobayashi Joggling Correction Video Download Help Teams Club Tricks Handouts 1st: Showy Motion - Stefan Brancel and Ben Hestness Magazine Process 2nd: Smirk - Reid Belstock and Warren Hammond Will Murray in Afghanistan 3rd: The Jugheads - Rory Bade, Michael Barreto, Alex Behr, Daniel Burke, Sean YEP Report Carney, Tom Gaasedelen, Joe Gould, Danny Gratzer, Conor Hussey, Reid Johnson, Griffin Kelley, Jonny Langholz, Jack Levy, Chris Lovdal, Mara Moettus, Chris Olson, Montreal Circus Festival Evan Peter, Scott Schultz, Joey Spicola, and Brenden Ying Stagecraft Corner Regional Festivals Juniors Best Catches IJA Games Winners 1st: David Ferman 2nd: Jack Denger FLIC Auditions 3rd: Patrick Fraser Busking Competition 1st: Cate Flaherty 2nd: Kevin Axtell 3rd: Gypsy Geoff See all the results online at: http://www.juggle.org/history/champs/champs2011.php Juggling Festivals: Davidson, NC S.Gloucestershire, UK Kansas City, MO Portland, OR Philadelphia, PA Asheville, NC St. Louis, MO Baden, PA Waidhofen, Austria North Goa, India Bali, Indonesia photo: Martin Frost WWW.JUGGLE.ORG Page 1 THE INTERNATIONAL JUGGLERS! ASSOCIATION August 2011 IJA Busking Competition, Most of us know there are a lot of great buskers amongst IJA members, but most of us don!t get to see their street acts in the wild. Stage shows and street shows are totally different dynamics, and different again from the zaniness that occurs on the Renegade stage. -

What's Happening at the IJA ?

THE INTERNATIONAL JUGGLERS’ ASSOCIATION January 2008 IJA eNewsletter editor: Don Lewis (email: [email protected]) Renew at http://www.juggle.org/renew What’s Happening at the IJA ? Happy New Year from the IJA Board In This Issue: Championship Rules Regional Festivals Host a Festival Video Party Green Club Tips Atlanta Groundhog Day Archive News Never Too Old... Austin JuggleFest XV Forum Changes World Juggling Day RIT Rochester Finance News IJA Insurance JAQ Montreal Video Projects Feedback & Opinion IJA Festval 2008 - Lexington Kentucky The 61st Annual IJA Juggling Festival will be held July 14-20, 2008, in Lexington, Kentucky, in the large, well-lit, climate-controlled juggling space of the Lexington Convention Center (with free wireless Internet). Specially invited guests include: * Performers from Ecole de Cirque de Quebec (Quebec Circus School) * Niels Duinker * Casey Boehmer * More to come... * * Youth Group Discount: Event Packages are available through June 1 for only $79 each to groups of 10 or more youths attending with a chaperone and registered together. For details, contact festival director Richard Kennison at [email protected]. Early Bird: Register by April 1 and pay only $159 for an Adult Event Package or $89 for a Youth-Senior Event Package. (Youth-Senior packages are for ages 11-17 and 65+.) Advanced: Register April 2 through June 15 and pay $189/Adult or $109/Youth-Senior. Last Minute: Register after June 15 and pay $229/Adult or $139/Youth-Senior. Full fest information (including online registration, hotel info, a room/ride-sharing forum and more) is available at: http://www.juggle.org/festival WWW.JUGGLE.ORG Page 1 THE INTERNATIONAL JUGGLERS’ ASSOCIATION January 2008 Throw a Juggling Video Party! by Steve Rahn Missing in Action? For those of you who have received your DVD of the IJA We have had reports of padded DVD mailers damaged in the 2007 Festival and have a group of juggling friends or mail and arriving without their contents. -

Rattlebacks for the Rest of Us Simon Jonesa) Department of Mechanical Engineering, Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, Terre Haute, Indiana 47803 Hugh E

Rattlebacks for the rest of us Simon Jonesa) Department of Mechanical Engineering, Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, Terre Haute, Indiana 47803 Hugh E. M. Hunt Engineering Dynamics and Vibration, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB21PZ, United Kingdom (Received 21 November 2018; accepted 18 June 2019) Rattlebacks are semi-ellipsoidal tops that have a preferred direction of spin (i.e., a spin-bias). If spun in one direction, the rattleback will exhibit seemingly stable rotary motion. If spun in the other direction, the rattleback will being to wobble and subsequently reverse its spin direction. This behavior is often counter-intuitive for physics and engineering students when they first encounter a rattleback, because it appears to oppose the laws of conservation of momenta, thus this simple toy can be a motivator for further study. This paper develops an accurate dynamic model of a rattleback, in a manner accessible to undergraduate physics and engineering students, using concepts from introductory dynamics, calculus, and numerical methods classes. Starting with a simpler, 2D planar rocking semi-ellipse example, we discuss all necessary steps in detail, including computing the mass moment of inertia tensor, choice of reference frame, conservation of momenta equations, application of kinematic constraints, and accounting for slip via a Coulomb friction model. Basic numerical techniques like numerical derivatives and time-stepping algorithms are employed to predict the temporal response of the system. We also present a simple and intuitive explanation for the mechanism causing the spin-bias of the rattleback. It requires no equations and only a basic understanding of particle dynamics, and thus can be used to explain the intriguing rattleback behavior to students at any level of expertise. -

Reprinted from Leatherneck, August, 1987

The Ugly Angel Memorial Foundation History Newsletter Vol. 2, No.1, Spring 2002 April 15, 1962: HMR(L)-362 Deploys to Soc Trang, RVN There’s a little game I play with myself sometimes. It goes like this; when you were in Vietnam, did it ever occur to you that “such and such” would ever happen in 2002. Well, it never, ever occurred to me, until a year or so ago, that I would ever be writing anything regarding the 40th anniversary of anything, never mind the anniversary of our own squadron being the first USMC tactical unit to deploy to Vietnam. But here it is, brothers. Forty years ago Archie and his Angels lifted off the deck of the USS Princeton and for all practical purposes began the USMC/Vietnam Helicopter experience. The Marine Corps was deeply involved in that conflict for another 11 years, as each of us well know. For most of us, the defining event of our lives occurred during those years. For some, it presented an opportunity to improve our lives and do things we had never imagined. For others, it ruined the life that we had dreamed of, and for some, it simply ended our lives. We all handle our involvement in different ways and that no doubt is how we will react to this important anniversary. The History Project presents this special issue to offer some focus to our thoughts. Within these pages are 3 articles written by 3 of the original “Archie’s Angels.” One is by Archie himself written shortly after his return for the U.S. -

(Multiplex) Juggling Sequences

Enumerating (multiplex) juggling sequences Steve Butler∗ Ron Grahamy Abstract We consider the problem of enumerating periodic σ-juggling sequences of length n for multiplex juggling, where σ is the initial state (or landing schedule) of the balls. We first show that this problem is equivalent to choosing 1's in a specified matrix to guarantee certain column and row sums, and then using this matrix, derive a recursion. This work is a generalization of earlier work of Fan Chung and Ron Graham. 1 Introduction Starting about 20 years ago, there has been increasing activity by discrete mathe- maticians and (mathematically inclined) jugglers in developing and exploring ways of representing various possible juggling patterns numerically (e.g., see [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 12, 14]). Perhaps the most prominent of these is the idea of a juggling sequence (or \siteswap", as it is often referred to in the juggling literature). The idea behind this approach is the following. For a given sequence T = (t1; t2; : : : ; tn) of nonnega- tive integers, we associate a (possible) periodic juggling pattern in which at time i, a ball is thrown so that it comes down at time i + ti. This is to be true for each i; 1 ≤ i ≤ n. Because we assume this is to be repeated indefinitely with period n, then in general, for each i and each k ≥ 0, a ball thrown at time i + kn will come down at time i + ti + kn. The usual assumption made for a sequence T to be a valid juggling sequence is that at no time do two balls come down at the same time. -

An Interactive Design System of Free-Formed Bamboo-Copters

Pacific Graphics 2016 Volume 35 (2016), Number 7 E. Grinspun, B. Bickel, and Y. Dobashi (Guest Editors) An Interactive Design System of Free-Formed Bamboo-Copters Morihiro Nakamura, Yuki Koyama, Daisuke Sakamoto and Takeo Igarashi The University of Tokyo Figure 1: Using our interactive design system, users can design free-formed, even asymmetric, bamboo-copters that can be easily fabricated and can successfully fly. Abstract We present an interactive design system for designing free-formed bamboo-copters, where novices can easily design free- formed, even asymmetric bamboo-copters that successfully fly. The designed bamboo-copters can be fabricated using digital fabrication equipment, such as a laser cutter. Our system provides two useful functions for facilitating this design activity. First, it visualizes a simulated flight trajectory of the current bamboo-copter design, which is updated in real time during the user’s editing. Second, it provides an optimization function that automatically tweaks the current bamboo-copter design such that the spin quality—how stably it spins—and the flight quality—how high and long it flies—are enhanced. To enable these functions, we present non-trivial extensions over existing techniques for designing free-formed model airplanes [UKSI14], including a wing discretization method tailored to free-formed bamboo-copters and an optimization scheme for achieving stable bamboo- copters considering both spin and flight qualities. Categories and Subject Descriptors (according to ACM CCS): I.3.6 [Computer Graphics]: Methodology and Techniques— Interaction techniques. I.3.8 [Computer Graphics]: Applications—. I.3.5 [Computer Graphics]: Computational Geometry and Object Modeling—Physically based modeling. 1.