Adventurer'shand B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1955-1958

THE COMMONWEALTH TRANS-ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION 1955-1958 HOW THE CROSSING OF ANTARCTICA MOVED NEW ZEALAND TO RECOGNISE ITS ANTARCTIC HERITAGE AND TAKE AN EQUAL PLACE AMONG ANTARCTIC NATIONS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree PhD - Doctor of Philosophy (Antarctic Studies – History) University of Canterbury Gateway Antarctica Stephen Walter Hicks 2015 Statement of Authority & Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not been previously submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Elements of material covered in Chapter 4 and 5 have been published in: Electronic version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume00,(0), pp.1-12, (2011), Cambridge University Press, 2011. Print version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume 49, Issue 1, pp. 50-61, Cambridge University Press, 2013 Signature of Candidate ________________________________ Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................. -

Stevenson-Waldie, Laura. 2001

Stevenson-Waldie, Laura. 2001 “The Sensational Landscape: The History of Sensationalist Images of the Arctic, 1818-1910,” 2001. Supervisor: William Morrison UNBC Library call number: G630.G7 S74 2001 ABSTRACT This thesis is a study of the public perception of the Arctic through explorers’ journals and the modern press in America and Britain. The underlying question of this thesis is what exactly was the role of the press in forming public opinions about Arctic exploration in general? Did newspaper editors in America and Britain simply report what they found interesting based upon their own knowledge of Arctic explorers’ journals, or did these editors create that public interest in order to profit from increased sales? From a historical perspective, these reasons relate to the growth of an intellectual and social current that had been gaining strength on the Western World throughout the nineteenth century: the creation of the mythic hero. In essence, the mythical status of Arctic explorers developed in Britain, but was matured and honed in the American press, particularly in the competitive news industry in New York where the creation of the heroic Arctic explorer resulted largely from the vicious competitiveness of the contemporary press. Although the content of published Arctic exploration journals in the early nineteenth century did not change dramatically, the accuracy of those journals did. Exploration journals up until 1850 tended to focus heavily on the conventions of the sublime and picturesque to describe these new lands. However, these views were inaccurate, for these conventions forced the explorer to view the Arctic very much as they viewed the Swiss Alps or the English countryside. -

BOLD ENDEAVORS: BEHAVIORAL LESSONS from POLAR and SPACE EXPLORATION Jack W

BOLD ENDEAVORS: BEHAVIORAL LESSONS FROM POLAR AND SPACE EXPLORATION Jack W. Stuster Anacapa Sciences, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA ABSTRACT Material in this article was drawn from several chapters of the author’s book, Bold Endeavors: Lessons from Polar and Space Anecdotal comparisons frequently are made between Exploration. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. 1996). expeditions of the past and space missions of the future. the crew gradually became afflicted with a strange and persistent Spacecraft are far more complex than sailing ships, but melancholy. As the weeks blended one into another, the from a psychological perspective, the differences are few condition deepened into depression and then despair. between confinement in a small wooden ship locked in the Eventually, crew members lost almost all motivation and found polar ice cap and confinement in a small high-technology it difficult to concentrate or even to eat. One man weakened and ship hurtling through interplanetary space. This paper died of a heart ailment that Cook believed was caused, at least in discusses some of the behavioral lessons that can be part, by his terror of the darkness. Another crewman became learned from previous expeditions and applied to facilitate obsessed with the notion that others intended to kill him; when human adjustment and performance during future space he slept, he squeezed himself into a small recess in the ship so expeditions of long duration. that he could not easily be found. Yet another man succumbed to hysteria that rendered him temporarily deaf and unable to speak. Additional members of the crew were disturbed in other ways. -

99-00 May No. 4

THE ANTARCTICAN SOCIETY 7338 Wayfarer Drive Fairfax Station, Virginia 22039 HONORARY PRESIDENT — MRS. PAUL A. SIPLE Vol. 99-00 May No. 4 Presidents: Dr. Carl R. Eklund, 1959-61 Dr. Paul A. Siple, 1961-62 Mr. Gordon D. Cartwright, 1962-63 BRASH ICE RADM David M. Tyree (Ret.), 1963-64 Mr. George R. Toney, 1964-65 Mr. Morton J. Rubin, 1965-66 Dr. Albert R Crary, 1966-68 As you can readily see, this newsletter is NOT announcing a speaker Dr. Henry M. Dater, 1968-70 program, as we have not lined anyone up, nor have any of you stepped Mr. George A. Doumani, 1970-71 Dr. William J. L. Sladen, 1971-73 forward announcing your availability. So we are just moving out with a Mr. Peter F. Bermel, 1973-75 Dr. Kenneth J. Bertrand, 1975-77 newsletter based on some facts, some fiction, some fabrications. It will be Mrs. Paul A. Siple, 1977-78 Dr. Paul C. Dalrymple, 1978-80 up to you to ascertain which ones are which. Good luck! Dr. Meredith F. Burrill, 1980-82 Dr. Mort D. Turner, 1982-84 Dr. Edward P. Todd, 1984-86 Two more Byrd men have been struck down -- Al Lindsey, the last of the Mr. Robert H. T. Dodson, 1986-88 Dr. Robert H. Rutford, 1988-90 Byrd scientists to die, and Steve Corey, Supply Officer, both of the 1933-35 Mr. Guy G. Guthridge, 1990-92 Byrd Antarctic Expedition. Al was a handsome man, and he and his wife, Dr. Polly A. Penhale, 1992-94 Mr. Tony K. Meunier, 1994-96 Elizabeth, were a stunning couple. -

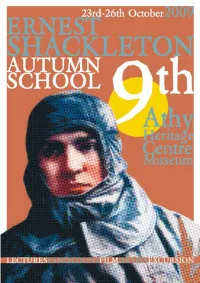

Sir Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Shackleton Born close to the village of Kilkea, FRIDAY 23rd October between Castledermot and Athy, in the south of County Kildare in 1874, Ernest Shackleton Official Opening & is renowned for his courage, his commitment to the welfare of his comrades and his Book Launch immense contribution to exploration and 7.30pm in Athy Heritage Centre - geographical discovery. The Shackleton family Museum first came to south Kildare in the early years of the eighteenth century. Ernest’s Quaker In association with the Erskine Press the forefather, Abraham Shackleton, established a multi-denominational school in the village school will host the launch of Regina Daly’s of Ballitore. This school was to educate such book notable figures as Napper Tandy, Edmund ‘The Shackleton Letters: Behind the Scenes of Burke, Cardinal Paul Cullen and Shackleton’s the Nimrod Expedition’. great aunt, the Quaker writer, Mary Leadbeater. Apart from their involvement in education, the extended family was also deeply involved in Shackleton the business and farming life of south Kildare. Having gone to sea as a teenager, Memorial Lecture Shackleton joined Captain Scott’s Discovery expedition (1901 – 1904) and, in time, was by Caroline Casey to lead three of his own expeditions to the Antarctic. His Endurance expedition (1914 – 8.15pm in Athy Heritage Centre - Museum 1916) has become known as one of the great epics of human survival. He died in 1922, at The founder and CEO of Kanchi (formerly South Georgia, on his fourth expedition to the known as The Aisling Foundation) Caroline is Antarctic, and – on his wife’s instructions – was buried there. -

INAUGURAL SEASON 2020-2021 Antarctica | Greenland & Iceland

EXPEDITION CRUISES INAUGURAL SEASON 2020-2021 Antarctica | Svalbard | Greenland & Iceland | Norway & Russia | Northwest Passage | North, Central & South America | Europe new Alaska & Canada Content 2020-21 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– We take you far beyond the ordinary 6-7 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Our Expedition Fleet 8-9 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– The future is green 10-11 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Antarctica 12-15 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Greenland & Iceland 16-19 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Russia 19 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Svalbard 20-23 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Norway 24-25 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Northwest Passage 26-27 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Alaska & Canada 28-29 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– North & Central America 30 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– South America 31 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Europe 32 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Extend your stay 32-33 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Terms and conditions 34-37 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– 2 “Ever since Hurtigruten started sailing polar waters back in 1893, we have been on a constant look out for new worlds to explore.” © HURTIGRUTEN Hurtigruten is an exploration company in the truest sense of the word; our mission is to bring adventurers to remote natural beauty around the world. Our experience in the feld is unparalleled, and we draw on our unique -

Scurvy? Is a Certain There Amount of Medical Sure, for Know That Sheds Light on These Questions

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2013; 43:175–81 Paper http://dx.doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2013.217 © 2013 Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh The role of scurvy in Scott’s return from the South Pole AR Butler Honorary Professor of Medical Science, Medical School, University of St Andrews, Scotland, UK ABSTRACT Scurvy, caused by lack of vitamin C, was a major problem for polar Correspondence to AR Butler, explorers. It may have contributed to the general ill-health of the members of Purdie Building, University of St Andrews, Scott’s polar party in 1912 but their deaths are more likely to have been caused by St Andrews KY16 9ST, a combination of frostbite, malnutrition and hypothermia. Some have argued that Scotland, UK Oates’s war wound in particular suffered dehiscence caused by a lack of vitamin C, but there is little evidence to support this. At the time, many doctors in Britain tel. +44 (0)1334 474720 overlooked the results of the experiments by Axel Holst and Theodor Frølich e-mail [email protected] which showed the effects of nutritional deficiencies and continued to accept the view, championed by Sir Almroth Wright, that polar scurvy was due to ptomaine poisoning from tainted pemmican. Because of this, any advice given to Scott during his preparations would probably not have helped him minimise the effect of scurvy on the members of his party. KEYWORDS Polar exploration, scurvy, Robert Falcon Scott, Lawrence Oates DECLaratIONS OF INTERESTS No conflicts of interest declared. INTRODUCTION The year 2012 marked the centenary of Robert -

The Reception and Commemoration of William Speirs Bruce Are, I Suggest, Part

The University of Edinburgh School of Geosciences Institute of Geography A SCOT OF THE ANTARCTIC: THE RECEPTION AND COMMEMORATION OF WILLIAM SPEIRS BRUCE M.Sc. by Research in Geography Innes M. Keighren 12 September 2003 Declaration of originality I hereby declare that this dissertation has been composed by me and is based on my own work. 12 September 2003 ii Abstract 2002–2004 marks the centenary of the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition. Led by the Scots naturalist and oceanographer William Speirs Bruce (1867–1921), the Expedition, a two-year exploration of the Weddell Sea, was an exercise in scientific accumulation, rather than territorial acquisition. Distinct in its focus from that of other expeditions undertaken during the ‘Heroic Age’ of polar exploration, the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition, and Bruce in particular, were subject to a distinct press interpretation. From an examination of contemporary newspaper reports, this thesis traces the popular reception of Bruce—revealing how geographies of reporting and of reading engendered locally particular understandings of him. Inspired, too, by recent work in the history of science outlining the constitutive significance of place, this study considers the influence of certain important spaces—venues of collection, analysis, and display—on the conception, communication, and reception of Bruce’s polar knowledge. Finally, from the perspective afforded by the centenary of his Scottish National Antarctic Expedition, this paper illustrates how space and place have conspired, also, to direct Bruce’s ‘commemorative trajectory’—to define the ways in which, and by whom, Bruce has been remembered since his death. iii Acknowledgements For their advice, assistance, and encouragement during the research and writing of this thesis I should like to thank Michael Bolik (University of Dundee); Margaret Deacon (Southampton Oceanography Centre); Graham Durant (Hunterian Museum); Narve Fulsås (University of Tromsø); Stanley K. -

Matthew Henson at the Top of the World Biography by Jim Haskins

Before Reading Matthew Henson at the Top of the World Biography by Jim Haskins VIDEO TRAILER KEYWORD: HML6-808 Why attempt the IMPOSSIBLE? Sailing across the ocean. Taking a walk on the moon. Once, these things were thought to be impossible. Then someone had the RI 3 Analyze in detail how a courage to try what had never been done. In the following selection, key individual, event, or idea is introduced, illustrated, you will see how a young explorer’s determination helped him go and elaborated in a text. RI 4 Determine the meaning of where nobody had gone before. words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative meanings. L 4b Use affixes as WEB IT What do you want to accomplish in your lifetime? Write clues to the meaning of a word. down one of your biggest ambitions in the center of a word web like the one shown. Then brainstorm different things you could do to make that achievement possible. take astronomy classes study all I can about outer space read books Become an about space Astronaut visit NASA 808 808-809_NA_L06PE-u07s01-brWrld.indd 808 12/31/10 5:13:40 PM Meet the Author text analysis: biography A biography is the true account of a person’s life, written Jim Haskins by another person. No two writers are the same, so every 1941–2005 biography is unique—even if many are about the same Bringing History to Light person. Still, all biographies share a few characteristics. Jim Haskins attended a segregated school in his Alabama hometown. -

A Century Ago : the Nansen Drift Fridtjof Nansen Wanted to Reach the Pole by Having His Boat Caught in the Ice and Letting Her Drift

www.taraexpeditions.org A century ago : the Nansen drift Fridtjof Nansen wanted to reach the pole by having his boat caught in the ice and letting her drift. He will miss his objective by some 800 km but will bring back all his crew despite three very harsh wintering. In 1895, a Norwegian succeeded in com- pleting the fi rst Arctic drift on the Fram, the boat that is Tara’s ancestor. Prolonged for three long polar winters, the mission, however, was not able to reach the pole. Fridtjof Nansen was 32 years old when he Her rounded shapes should prevent the ice from March 1895, Nansen decides to leave the boat had begun on the journey. During the summer, started on his Arctic drift. His aim was to get crushing her, but it is especially her sturdiness and go with a companion to the North Pole the pack ice becomes more and more impracti- as close to the North pole as possible. It is after that enables her to resist to the pack ice grip : the by sledge. Th e two men are equipped with cable but at the end of August, they accost on having discovered in the south west of Green- hull is more than 80 centimetres thick. light kayaks and take 630 kg of equipment with land on the Franz-Joseph archipelago. Th ey re- land the remains of a vessel crushed by the ice, With a crew of 13 men, Nansen leaves Oslo them. After 23 days on the go, they give up on solve to spend their third Arctic winter. -

Inventory Acc.12696 William Laird Mckinlay

Acc.12696 December 2006 Inventory Acc.12696 William Laird McKinlay National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland Correspondence and papers of William Laird McKinlay, Glasgow. Background William McKinlay (1888-1983) was for most of his working life a teacher and headmaster in the west of Scotland; however the bulk of the papers in this collection relate to the Canadian National Arctic Expedition, 1913-18, and the part played in it by him and the expedition leader, Vilhjalmur Stefansson. McKinlay’s account of his experiences, especially those of being shipwrecked and marooned on Wrangel Island, off the coast of Siberia, were published by him in Karluk (London, 1976). For a rather more detailed list of nos.1-27, and nos.43-67 (listed as nos.28-52), see NRA(S) survey no.2546. Further items relating to McKinlay were presented in 2006: see Acc.12713. Other items, including a manuscript account of the expedition and the later activities of Stefansson – much broader in scope than Karluk – have been deposited in the National Archives of Canada, in Ottawa. A small quantity of additional documents relating to these matters can be found in NRA(S) survey no.2222, papers in the possession of Dr P D Anderson. Extent: 1.56 metres Deposited in 1983 by Mrs A.A. Baillie-Scott, the daughter of William McKinlay, and placed as Dep.357; presented by the executor of Mrs Baillie-Scott’s estate, November 2006. -

Fridtjof Nansen, One of Norway's Most Famous Sons

Paraplegia 25 (1987) 27-31 © 1987 International Medical Society of Paraplegia FridtjofNansen: Neuro-anatomical Discoveries, Arctic Explorations, and Humanitarian Deeds Abrahatn Ohry, M.D.t and Karin Ohry-Kossoy, M.A. t Neurological Rehabilitation Department, Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer, Israel 'Man wants to know, and when he ceases to do so, he is no longer a man' F. Nansen The IMSOP Meeting took place in Oslo on the 125th anniversary of Nansen's birth. Apart from his Arctic explorations, his political and humanitarian activities, he first pointed out that the posterior root fibres divide on entering the spinal cord into ascending and descending branches. This article is dedicated to the memory of a great Norwegian. The 1986 IMSOP Meeting in Oslo took place at the time of the 125th anniver sary of the birth of Fridtjof Nansen, one of Norway's most famous sons. He was an extremely gifted man with lofty ideals who left an enduring mark in all the fields in which he was active. Our own particular interest in him, however, con centrates on his neuro-anatomical discoveries (Christensen, 1961; Vogt, 1961). Nansen was born in Norway in 1861. His family was of distinguished Danish origin. The orientations of his adult life were already clearly apparent during his childhood: at school he excelled in the sciences and in drawing, but also spent much time outdoors, skiing and exploring nature. In 1880 Nansen became a zoology student at the University of Christiania in Oslo, which enabled him to combine his interest in science with his love for outdoor life.