Heroes, Mates and Family

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Football and Contracts 101

REGULARS SPORT AND THE LAW 'Williams, c’est pour toi’: Football and Contracts 101 Sport is often depicted as a substitute for war. Judging Here was a Polynesian Kiwi, making it good in Australian by headlines in Australia, sporting battles eclipse rugby league, before setting himself up on the French real battles. As July turned into August this year, Mediterranean to pursue both wealth and a dream of international attention focused on the Russian-Georgian playing rugby for the All Blacks. Williams’ tale epitomises war. But here, a dispute involving Sonny Bill Williams, the internationalisation of even club football. a young rugby league star, generated more fascination. The second reason the Williams dispute became That the dispute was played out in the courts, and not a celebrated case was its litigation. The otherwise on field, reminds us how central commercial law has REFERENCES impotent Bulldogs, backed by the N R L or National become not just to the professional sports industry, but 1. Roy Masters, ‘NRL Seeks Image Tax Rugby League (a consortium of News Ltd and the A RL the very spectacle and diversion that sport has become. Breaks for all Players’, Sydney Morning- sporting body) determined to enlist the law. Herald (Sydney), 30 July 2008, 40. Williams is a Polynesian N ew Zealander, with an Williams’ standard form employment contract 2. Lumley v Wagner ( 1852) 42 ER 687. unusual footballing talent by virtue of his athleticism, contained several negative covenants. One required 3. ‘Williams, this is for you’. strength and marketable persona. (Although, given the him to play in only rugby league games sanctioned by 4. -

Boxing, Governance and Western Law

An Outlaw Practice: Boxing, Governance and Western Law Ian J*M. Warren A Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Human Movement, Performance and Recreation Victoria University 2005 FTS THESIS 344.099 WAR 30001008090740 Warren, Ian J. M An outlaw practice : boxing, governance and western law Abstract This investigation examines the uses of Western law to regulate and at times outlaw the sport of boxing. Drawing on a primary sample of two hundred and one reported judicial decisions canvassing the breadth of recognised legal categories, and an allied range fight lore supporting, opposing or critically reviewing the sport's development since the beginning of the nineteenth century, discernible evolutionary trends in Western law, language and modern sport are identified. Emphasis is placed on prominent intersections between public and private legal rules, their enforcement, paternalism and various evolutionary developments in fight culture in recorded English, New Zealand, United States, Australian and Canadian sources. Fower, governance and regulation are explored alongside pertinent ethical, literary and medical debates spanning two hundred years of Western boxing history. & Acknowledgements and Declaration This has been a very solitary endeavour. Thanks are extended to: The School of HMFR and the PGRU @ VU for complete support throughout; Tanuny Gurvits for her sharing final submission angst: best of sporting luck; Feter Mewett, Bob Petersen, Dr Danielle Tyson & Dr Steve Tudor; -

Fair Go’ Principle Which Suggests That Everyone Is Entitled to Fairness by Way of Shared Opportunity – Such As with Education, Health, Social Security, and So On

Australian society has long been imbued with a ‘fair go’ principle which suggests that everyone is entitled to fairness by way of shared opportunity – such as with education, health, social security, and so on. For advocates, this mantra underpins a society that, while unequal, is not characterized by vast differences in wealth and living standards (Herscovitch, 2013). To critics, though, the ‘fair go’ notion is either idealistic or completely unrealistic, as well as a distraction from entrenched differences of opportunity and power in Australian society (Lawrence, 2017). For Indigenous Australians, the notion of a ‘fair go’ in a society in which generations of Aboriginal peoples have suffered manifestly is particularly fraught (Tatz, 2017).1 Even the semantics of a ‘fair go’ can be construed as discriminatory by way of ‘race’:2 for example, ‘fairness’ has long focused on opportunities for fair skinned (i.e. White) Australians (Fotinopoulos, 2017). Revelations that in many parts of Australia during the early to mid-late twentieth century, Aboriginal children were forcibly removed from families and placed in foster care – under the guise of welfare – prompted a report into what became known as the Stolen Generations (Murphy, 2011). In 2008, the Federal Government issued a national apology and committed to a reconciliation process. This includes ‘closing the gap’ initiatives featuring twin efforts: to help all Australians come to terms with a harrowing history of racial discrimination and conflict, and to catalyze improvements to the lives of Aboriginal peoples (Gunstone, 2017; Kowal, 2015). In this article we are interested in the question of a ‘fair go’ for Indigenous peoples, particularly the role of Aboriginal voices in seeking to (re)shape symbols of identity, representation, and nationality. -

Developing Identity As a Light-Skinned Aboriginal Person with Little Or No

Developing identity as a light-skinned Aboriginal person with little or no community and/or kinship ties. Bindi Bennett Bachelor Social Work Faculty of Health Sciences Australian Catholic University A thesis submitted to the ACU in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy 2015 1 Originality statement This thesis contains no material published elsewhere (except as detailed below) or extracted in whole or part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No parts of this thesis have been submitted towards the award of any other degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgment in the main text of the thesis. All research procedures reported in the thesis received the approval of the relevant Ethics Committees. This thesis was edited by Bruderlin MacLean Publishing Services. Chapter 2 was published during candidature as Chapter 1 of the following book Our voices : Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social work / edited by Bindi Bennett, Sue Green, Stephanie Gilbert, Dawn Bessarab.South Yarra, Vic. : Palgrave Macmillan 2013. Some material from chapter 8 was published during candidature as the following article Bennett, B.2014. How do light skinned Aboriginal Australians experience racism? Implications for Social Work. Alternative. V10 (2). 2 Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................... -

Indigenous Australian Art Photography: an Intercultural Approach

57 Pater, Walter, 1948. Walter Pater, Selected Works, ed. Richard Aldington. London: William Heinemann. Ruskin, John, [1853] 1904. The Stones of Venice, Volume II. London: George Allen. Smith, Geoffrey and Smith, Damian, 2003. Sidney Nolan: Desert and Drought. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria. _________________________________________________________________ Indigenous Australian Art Photography: an Intercultural Approach. Elisabeth Gigler, University of Klagenfurt Aboriginal art has become a big business over the last decades. This demand for Indigenous art, however, has mostly been reduced to paintings. Art photography produced by Indigenous Australian artists is hardly an issue within this context and mostly not associated with the term “Aboriginal art” in mainstream society and on the mainstream art markets. This is also, why most people, when I told them about my PhD project and the title of it, “An Intercultural Perspective on Indigenous Australian Art Photography”—they connected my topic immediately with photographs taken by Europeans of Indigenous people somewhere in the outback in Australia. Or, another common idea was that it is about art projects in which Indigenous Australian people are given cameras by Europeans in order to take photos themselves. So, in short, what people mostly connected to the term “Indigenous Australian photography” was not the view about an independent contemporary art movement and individual art projects as they are common all over the world in a variety of ways, but they mostly connected it to forms of colonization, European activities, European art. This brief example shows that for some reason, many people still connect the term ‘Indigenous’ with a view about people living in an indefinite, fossiled past (Langton, 1993:81), which is still a common stereotype about Indigenous Australian people, and in fact a very problematic one. -

The Role of the Medical Profession in Boxing

CONTROVERSY 513 The not-so-sweet science defeat of Max Schmelling in 1938 J Med Ethics: first published as 10.1136/jme.2003.003541 on 5 October 2004. Downloaded from ....................................................................................... united Americans of all races and stifled Hitler’s claim of Aryan super- iority. If a consequentialist position is The not-so-sweet science: the role of the adopted, based on a diachronic evalua- tion of boxing, then boxing should be medical profession in boxing permitted. It is tempting, for those unfamiliar D K Sokol with the sport, to interpret too literally the gruesome pre-fight threats of box- ................................................................................... ers. The animosity is rarely genuine; it is an essential component of the market- The medical profession’s role should be limited to advice and ing plan, as well as an exercise in information psychological intimidation. Dr Herrera’s assertion that fighters ‘‘can he medical establishment’s desire to other high risk sports, claiming that a even predict the killing before the fight, interfere with the autonomous boxer can kill his opponent without for the press’’ is irrelevant. The meta- Twishes of boxers seems at odds with breaking any rules whereas this is not phors of boxing are indeed more belli- the principle of respect for autonomy the case in other sports. This last cose than in other sports, but critics prevalent in contemporary biomedical statement is surely false. A hard hitting should interpret the metaphors as lin- practice. I argue that the role of the rugby tackle can propel a player back- guistic flourishes, not as literal expres- medical profession in boxing should be wards causing him to suffer fatal spinal sions of intent. -

4 October 2018

Looking for past editions of Eye on Q? Find these on TEQ's corporate website. 4 October 2018 Aussies flock to Queensland The latest National Visitor Survey data shows Australians spent more money in Queensland over the past 12 months than ever before. The increase in spending of more than 10 per cent generated a record $17 billion in overnight visitor expenditure for Queensland for the first time. The state also welcomed a record 22.5 million domestic visitors - nearly five per cent growth. The figures for the year ending June 2018 were released yesterday and showed every region across the state experienced growth in visitor expenditure. Queensland's swathe of bumper major events were a significant contributing factor - from the Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games held in four event cities, to Manny Pacquiao v Jeff Horn (Battle of Brisbane), the Marvel: Creating the Cinematic Universe exhibition and 70 destination events - all of which drove visitation and expenditure across the state. See the latest domestic visitor statistics Cruise sector growth The latest cruise industry data reveals that cruise ship days to Queensland increased by 11 per cent over the past year, with 860,000 passengers and crew spending $501 million. The growth was supported by emerging regions like Gladstone, Thursday Island, Townsville, Fraser Island and Mooloolaba providing cruise lines with more opportunities to visit the state's unique destinations. Looking ahead, cruise lines will ramp up a record number of visits to 11 Queensland ports over the next seven months, including Carnival Australia who plan 247 calls alone - a 30 per cent increase on the last cruise season. -

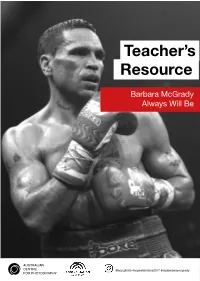

Teacher's Resource

Teacher’s Resource Barbara McGrady Always Will Be @acp.photo #acpexhibitions2017 #acpbarbaramcgrady Contents Page Teacher’s Resource 2 About the Australian Centre for Photography 3 About Reconciliation Australia 4 About the Resource 5 About the Exhibition 6 About the Photographer 7 Exercise 1: Redfern and Self-Determination 9 Exercise 2: Media & Sport 11 Exercise 3: Portraits & Community 13 Glossary 14 Resources & Links 15 Curriculum Table The Australian Centre for Photography acknowledges and pays respect to the past, present and future Traditional Custodians and Elders of Country featured in this exhibition and across the nation. We celebrate the continuation of cultural, spiritual and educational practices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This education kit has been developed in partnership with Reconciliation Australia to accompany the Australian Centre for Photography’s 2017 exhibition Barbara McGrady: Always Will Be, guest curated by Sandy Edwards. Images Cover Image: Barbara McGrady, Anthony Mundine V Joshua Clotty, WBA middle weight title fight, Entertainment Centre, April 2014 Pages 2, 4-5: Installation images from Barbara McGrady:Always Will Be. Courtesy and © Michael Waite / ACP 2017. Pages 6: Barbara McGrady, Closing Communitues rally, 2015 Pages 7: Barbara McGrady, Gary Foley Free Gaza Boomalli exhibition, 2012 Pages 8: Barbara McGrady, Anthony ‘Choc’ Mundine vs Joshua Clotty, WBA middle weight title fight, Newcastle Entertainment Centre, 2012 Pages 9: Barbara McGrady, Jonathon Thurston Indigenous All Stars, 2015 Pages 10: Barbara McGrady, Jessica Mauboy, Premiere The Sapphires film, State Theatre, Sydney, 2013 Pages 11: Barbara McGrady, Sister Girls stylin up, Mardi Gras, 2013 The Australian Centre for Photography About the Schools Program The Australian Centre for Photography is a not for profit arts organisation dedicated to photography and new media. -

Journals of the Senate

2345 2002-03 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA JOURNALS OF THE SENATE No. 97 THURSDAY, 11 SEPTEMBER 2003 Contents 1 Meeting of Senate ................................................................................................ 2347 2 Notices.................................................................................................................. 2347 3 Order of Business—Rearrangement.................................................................... 2347 4 Postponements...................................................................................................... 2347 5 Senators’ Interests—Standing Committee—Proposed Variation....................... 2347 6 Days of Meeting—Legislation Committees—Estimates Hearings— Variation......................................................................................................... 2348 7 Foreign Affairs—Papua New Guinea ................................................................. 2348 8 Science and Technology—Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty ............... 2348 9 World Suicide Prevention Day ............................................................................ 2349 10 Health—Tobacco ................................................................................................. 2349 11 Indigenous Australians—Anthony Mundine ...................................................... 2350 12 Environment—Barrow Island—Proposed Gas Development............................ 2350 13 Indigenous Australians—Political Representation............................................. -

Platformed Racism: the Adam Goodes War Dance and Booing Controversy on Twitter, Youtube, and Facebook

PLATFORMED RACISM: THE ADAM GOODES WAR DANCE AND BOOING CONTROVERSY ON TWITTER, YOUTUBE, AND FACEBOOK Ariadna Matamoros-Fernández BA Autonomous University of Barcelona MA University of Amsterdam Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Digital Media Research Centre Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology 2018 Keywords Platformed racism Race Racism Whiteness Critical Race Theory Colour-blindness Digital platforms Twitter Facebook YouTube Social media Technocultures Memetic culture Media practices Visual media Multiplatform issue mapping Platform governance i ii Abstract This research interrogates the material politics of social media platforms, and their role in online racism. Platforms have altered how people search, find, and share information, and how social interactions take place online. This new era of user practices, micro-communication cultures, and an increasing algorithmic shaping of sociability, opens up new research endeavours to understand communication as a cultural practice. While platforms are reluctant to acknowledge that they work as media companies, and present themselves as being ‘neutral’, they intervene in public discourse through their design, policies, and corporate decisions. This intervention is increasingly under public scrutiny at a time when racist and sexist speech is thriving online. The entanglement between user practices and platforms in the reinforcement of racism is the focus of my research. Specifically, I argue that this entanglement -

“The Legendary Fight of the Ages” “Sugar” Shane Mosley Vs Anthony Mundine Late October 2013 Sydney, Australia

“THE LEGENDARY FIGHT OF THE AGES” “SUGAR” SHANE MOSLEY VS ANTHONY MUNDINE LATE OCTOBER 2013 SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA The wait is finally over as a mega fight heads for Australia. In Late October 2013 “The Legendary Fight of the Ages” takes place in Sydney, Australia. Two of the world’s most legendary fighters from two different continents face off in what should be one of the most blockbuster fights of our time. From the United States is “Sugar” Shane Mosley who is one greatest boxers of all time taking on the Australia Legend, Anthony Mundine. This match up shapes up to be one of the best fights in the history of boxing. Fans across the world will be treated to a battle which is truly a test of what champions are all about. It goes without saying that Shane Mosely in his career has fought all the greatest boxers in his weight class in the last two decades. Compiling a record of 47-8-1 with 39 KO’s. In 2000 Mosely was the elected by the World Boxing Hall of Fame Fighter of the Year. He has held World Titles from Lightweight, Welterweight and Light-Middleweight. He won his first title in 1997 as a Lightweight and just last year fought for World Title at Jr. Middleweight. In his career he has fought the likes of Saul Alverez, Manny Pacquiao, Floyd Mayweather Jr. Miguel Cotto, Fernando Vargas and of course, Oscar De La Hoya. Hailing from Down Under is Anthony “The Man” Mundine who is undoubtabtly one of the greatest Australia’s boxers of all time. -

Australian Media Representations of Sport and Terrorism

‘Here be Dragons, Here be Savages, Here be bad Plumbing’: Australian Media Representations of Sport and Terrorism Professor Kristine Toohey, Department of Tourism, Leisure, Hotel and Sport Management Griffith University Australia Phone: 61 7 5552 9205 Fax: 61 2 5552 8507 Email: [email protected] Associate Professor Tracy Taylor, Graduate School of Business, University of Technology, Sydney Phone: 61 2 95143664 Fax: 61 2 95143557 Email: [email protected] Word length: 8408 1 Abstract As ‘Propaganda Theorists’ argue, an examination of key discourses can enhance our understanding of how economic, political and social debate is shaped by mainstream media reporting. In this article we present content and discourse analysis of Australian media reporting on the nexus of sport and terrorism. Examining newspaper reports over a five-year period, from 1996-2001, which included the 11 September 2001 terrorist tragedy in the United States (9/11), provides useful insights into how public discourse might be influenced with regard to sport and terrorism interrelationships. The results of the media analysis suggest that hegemonic tropes are created around sport and terrorism. The distilled message is one of good and evil, with homilies of sport employed in metaphors for western society and its values. The reactions and responses of sport administrators and athletes to terrorist acts and the threat of terrorism to sport are used to exemplify these ideals, providing newspaper readers a context within which to localize meaning and relevance. Keywords: terrorism, sport, media 2 Introduction In this paper we investigate both quantitative variances and qualitative nuances in Australian newspaper articles covering the topic of ‘sport’ and ‘terrorism’, pre and post the terrorist attacks in the United States on 11 September 2001 (known colloquially as 9/11).