Essential Tremor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

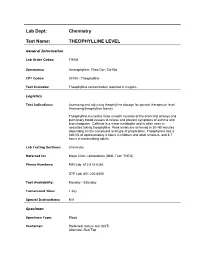

Theophylline Level

Lab Dept: Chemistry Test Name: THEOPHYLLINE LEVEL General Information Lab Order Codes: THEM Synonyms: Aminophylline, Theo-Dur, Slo-Bid CPT Codes: 80198 - Theophylline Test Includes: Theophylline concentration reported in mcg/mL. Logistics Test indications: Assessing and adjusting theophylline dosage for optimal therapeutic level. Assessing theophylline toxicity Theophylline is used to relax smooth muscles of the bronchial airways and pulmonary blood vessels to relieve and prevent symptoms of asthma and bronchospasm. Caffeine is a minor metabolite and is often seen in neonates taking theophylline. Peak levels are achieved in 30–90 minutes depending on the compound and type of preparation. Theophylline has a half-life of approximately 4 hours in children and adult smokers, and 8.7 hours in nonsmoking adults. Lab Testing Sections: Chemistry Referred to: Mayo Clinic Laboratories (MML Test: THEO) Phone Numbers: MIN Lab: 612-813-6280 STP Lab: 651-220-6550 Test Availability: Monday - Saturday Turnaround Time: 1 day Special Instructions: N/A Specimen Specimen Type: Blood Container: Preferred: Serum Gel (SST) Alternate: Red Top Draw Volume: 1.5 mL blood Processed Volume: 0.5 mL (Minimum: 0.25 mL) serum Collection: Routine blood collection Special Processing: Lab Staff: Centrifuge specimen within 2 hours of collection. Store and ship at refrigerated temperature. Patient Preparation: None Sample Rejection: Mislabeled or unlabeled specimen; gross hemolysis Interpretive Reference Range: Therapeutic: Bronchodilation: 8.0-20.0 mcg/mL Neonatal apnea (< or =4 weeks old): 6.0-13.0 mcg/mL Interpretation: Response to theophylline is directly proportional to the serum level. Patients usually receive the best response when the serum level is above 8.0 mcg/mL, with minimal toxicity experienced as long as the level is less than or equal to 20.0 mcg/mL Critical Values: >20.0 mcg/mL Limitations: Coadministration of cimetidine and erythromycin will significantly inhibit theophylline clearance, requiring dosagereduction. -

Study of Adulterants and Diluents in Some Seized Captagon-Type Stimulants

MedDocs Publishers ISSN: 2638-1370 Annals of Clinical Nutrition Open Access | Mini Review Study of Adulterants and Diluents in Some Seized Captagon-Type Stimulants Ali Zaid A Alshehri1,2*; Mohammed saeed Al Qahtani1,3; Mohammed Aedh Al Qahtani1,4; Abdulhadi M Faeq1,5; Jawad Aljohani1,6; Ammar AL-Farga7 1Department of Medical Laboratory Technology, College of Applied Medical Sciences, University of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia 2Poison Control and Medical Forensic Chemistry Center, Ministry of Health, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia 3Khammis Mushayte Maternity & Children Hospital, Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia 4Ahad Rufidah General, Hospital, Aseer, Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia 5Comprehensive Specialized Clinics of Security Forces in Jeddah, Ministry of Interior, Saudi Arabia 6Compliance Department, Yanbu Health Sector, Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia 7Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, University of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia *Corresponding Author(s): Ali Zaid A Alshehri Department of Medical Laboratory Technology, College of Applied Medical Sciences, University of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia Email: [email protected] Received: Apr 27, 2020 Accepted: Jun 05, 2020 Published Online: Jun 10, 2020 Journal: Annals of Clinical Nutrition Publisher: MedDocs Publishers LLC Online edition: http://meddocsonline.org/ Copyright: © Alshehri AZA (2020). This Article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Introduction ATS are synthetic compounds belonging to the class of stimu- and heroin users combined [3,4]. Fenethylline, 7-(2-amethyl lants that excite the Central Nervous System (CNS) to produce phenyl-amino ethyl)-theophylline, is a theophylline derivative of adrenaline-like effects such as amphetamine, methamphet- amphetamine. It is a psychoactive drug which is similar to am- amine, fenethylline, methylphenidate and dextroamphetamine phetamine in many ways [5]. -

Reviews Insights Into Pathophysiology from Medication-Induced Tremor

Freely available online Reviews Insights into Pathophysiology from Medication-induced Tremor 1* 1 1 1 John C. Morgan , Julie A. Kurek , Jennie L. Davis & Kapil D. Sethi 1 Movement Disorders Program Parkinson’s Foundation Center of Excellence, Department of Neurology, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, GA, USA Abstract Background: Medication-induced tremor (MIT) is common in clinical practice and there are many medications/drugs that can cause or exacerbate tremors. MIT typically occurs by enhancement of physiological tremor (EPT), but not all drugs cause tremor in this way. In this manuscript, we review how some common examples of MIT have informed us about the pathophysiology of tremor. Methods: We performed a PubMed literature search for published articles dealing with MIT and attempted to identify articles that especially dealt with the medication’s mechanism of inducing tremor. Results: There is a paucity of literature that deals with the mechanisms of MIT, with most manuscripts only describing the frequency and clinical settings where MIT is observed. That being said, MIT emanates from multiple mechanisms depending on the drug and it often takes an individualized approach to manage MIT in a given patient. Discussion: MIT has provided some insight into the mechanisms of tremors we see in clinical practice. The exact mechanism of MIT is unknown for most medications that cause tremor, but it is assumed that in most cases physiological tremor is influenced by these medications. Some medications (epinephrine) that cause EPT likely lead to tremor by peripheral mechanisms in the muscle (b-adrenergic agonists), but others may influence the central component (amitriptyline). -

Adenosine Strongly Potentiates Pressor Responses to Nicotine in Rats (Caffeine/Blood Pressure/Sympathetic Nervous System) REID W

Proc. Nadl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 81, pp. 5599-5603, September 1984 Neurobiology Adenosine strongly potentiates pressor responses to nicotine in rats (caffeine/blood pressure/sympathetic nervous system) REID W. VON BORSTEL, ANDREW A. RENSHAW, AND RICHARD J. WURTMAN Laboratory of Neuroendocrine Regulation, Department of Nutrition and Food Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139 Communicated by Walle J. H. Nauta, May 14, 1984 ABSTRACT Intravenous infusion of subhypotensive doses epinephrine output during nerve stimulation is decreased (6). of adenosine strongly potentiates the pressor response of anes- Adenosine can be produced ubiquitously and is present in thetized rats to nicotine. A dose of nicotine (40 jpg/kg, i.v.), plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (7, 8); the nucleoside can which, given alone, elicits a peak increase in diastolic pressure therefore potentially act at a number of different loci, both of -15 mm Hg, increases pressure by -70 mm Hg when arte- central and peripheral, within the complex neural circuitry rial plasma adenosine levels have been increased to 2 puM from involved in the regulation of a single physiological function, a basal concentration of =1 puM. The pressor response to ciga- such as maintenance of blood pressure or heart rate. Neither rette smoke applied to the lungs is also strongly potentiated normal plasma adenosine levels nor the relative and absolute during infusion of adenosine. Slightly higher adenosine con- sensitivities of neural and cellular processes to adenosine centrations (-4 jaM) attenuate pressor responses to electrical have been well characterized in intact animals. The studies stimulation of preganglionic sympathetic nerves, or to injec- described below explore the effects of controlled measured tions of the a-adrenergic agonist phenylephrine, but continue alterations in arterial plasma adenosine concentrations on to potentiate pressor responses to nicotine. -

Narco-Terrorism Today: the Role of Fenethylline and Tramadol

Narco-terrorism today: the role of fenethylline and tramadol Introduction The relationship between psychoactive substances and violent crimes such as war acts and terrorism dates long back in history. Viking warriors famously fought in a trance-like state, probably as a result of taking agaric "magic" mushrooms and bog myrtle (McCarthy, 2016). More recently, under the German Nazis’ Third Reich, methamphetamine gained an extreme popularity, despite an official “drug-free” propaganda. Under the trademark Pervitin, it could be sold without prescription until 1939, and it was not regulated by the Reich Opium Law of 1941. Pervitin was commonly used in recreational and working settings, and, of course, the stimulant was shipped to German soldiers when the troops invaded France, allowing them to march sleepless for 36 to 50 hours (Ohler, 2016). On the other side, Benzedrine, a racemic mixture of amphetamine initially developed as a bronchodilator, was the stimulant of choice of the Allied forces during World War II (McCarthy, 2016). Vietnam War (1955-1975) is considered to be the first “pharmacological war” of modern history, so called due to an unprecedented high level of consumption of psychoactive substances by military personnel (Kamienski, 2016). In 1971, a report by the House Select Committee on Crime revealed that from 1966 to 1969, the US armed forces had used 225 million tablets of stimulants, mostly Dexedrine (dextroamphetamine), an amphetamine derivative that is nearly twice as strong as the Benzedrine used in the Second World War (Kamienski, 2016). The use of illicit drugs such as stimulants or painkillers by terrorists or insurgents while undertaking their terrorist activities has been hypothesized but still needs further documentation. -

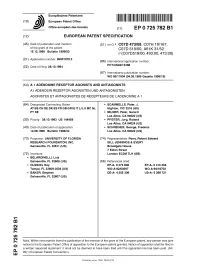

A 1 Adenosine Receptor Agonists and Antiagonists

Europaisches Patentamt (19) European Patent Office Office europeenpeen des brevets EP 0 725 782 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) intci.6: C07D 473/08, C07H 19/167, of the grant of the patent: C07D 519/00, A61K 31/52 15.12.1999 Bulletin 1999/50 // (C07D51 9/00, 493:00, 473:00) (21) Application number: 95901070.3 (86) International application number: PCT/US94/12388 (22) Date of filing: 28.10.1994 (87) International publication number: WO 95/11904 (04.05.1995 Gazette 1995/19) (54) A 1 ADENOSINE RECEPTOR AGONISTS AND ANTAGONISTS A1 ADENOSIN REZEPTOR AGONISTEN UND ANTAGONISTEN AGONISTES ET ANTAGONISTES DE RECEPTEURS DE L'ADENOSINE A 1 (84) Designated Contracting States: • SCAMMELLS, Peter, J. AT BE CH DE DK ES FR GB GR IE IT LI LU MC NL Highton, VIC 3216 (AU) PT SE • MILNER, Peter, Gerard Los Altos, CA 94022 (US) (30) Priority: 28.10.1993 US 144459 • PFISTER, Jurg, Roland Los Altos, CA 94024 (US) (43) Date of publication of application: • SCHREINER, George, Frederic 14.08.1996 Bulletin 1996/33 Los Altos, CA 94022 (US) (73) Proprietor: UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA (74) Representative: Perry, Robert Edward RESEARCH FOUNDATION, INC. GILL JENNINGS & EVERY Gainesville, FL 32611 (US) Broadgate House 7 Eldon Street (72) Inventors: London EC2M 7LH (GB) • BELARDINELLI, Luiz Gainesville, FL 32605 (US) (56) References cited: • OLSSON, Ray EP-A- 0 374 808 EP-A- 0 415 456 Tampa, FL 33609-3504 (US) WO-A-92/00297 WO-A-94/16702 • BAKER, Stephen DE-A- 4 205 306 US-A- 5 288 721 Gainesville, FL 32607 (US) DO CM 00 Is- lO CM Is- Note: Within nine months from the publication of the mention of the grant of the European patent, any person may give notice the Patent Office of the Notice of shall be filed in o to European opposition to European patent granted. -

Methylxanthines and Neurodegenerative Diseases: an Update

nutrients Review Methylxanthines and Neurodegenerative Diseases: An Update Daniel Janitschke 1,† , Anna A. Lauer 1,†, Cornel M. Bachmann 1, Heike S. Grimm 1, Tobias Hartmann 1,2 and Marcus O. W. Grimm 1,2,* 1 Experimental Neurology, Saarland University, 66421 Homburg/Saar, Germany; [email protected] (D.J.); [email protected] (A.A.L.); [email protected] (C.M.B.); [email protected] (H.S.G.); [email protected] (T.H.) 2 Deutsches Institut für DemenzPrävention (DIDP), Saarland University, 66421 Homburg/Saar, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: Methylxanthines (MTX) are purine derived xanthine derivatives. Whereas naturally occurring methylxanthines like caffeine, theophylline or theobromine are widely consumed in food, several synthetic but also non-synthetic methylxanthines are used as pharmaceuticals, in particular in treating airway constrictions. Besides the well-established bronchoprotective effects, methylxanthines are also known to have anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative properties, mediate changes in lipid homeostasis and have neuroprotective effects. Known molecular mechanisms include adenosine receptor antagonism, phosphodiesterase inhibition, effects on the cholinergic system, wnt signaling, histone deacetylase activation and gene regulation. By affecting several pathways associated with neurodegenerative diseases via different pleiotropic mechanisms and due to its moderate side effects, intake of methylxanthines have been suggested to be an interesting approach in dealing with neurodegeneration. Especially in the past years, the impact of methylxanthines in neurodegenerative diseases has been extensively studied and several new aspects have been elucidated. In this review Citation: Janitschke, D.; Lauer, A.A.; Bachmann, C.M.; Grimm, H.S.; we summarize the findings of methylxanthines linked to Alzheimer´s disease, Parkinson’s disease Hartmann, T.; Grimm, M.O.W. -

Alphabetical Listing of ATC Drugs & Codes

Alphabetical Listing of ATC drugs & codes. Introduction This file is an alphabetical listing of ATC codes as supplied to us in November 1999. It is supplied free as a service to those who care about good medicine use by mSupply support. To get an overview of the ATC system, use the “ATC categories.pdf” document also alvailable from www.msupply.org.nz Thanks to the WHO collaborating centre for Drug Statistics & Methodology, Norway, for supplying the raw data. I have intentionally supplied these files as PDFs so that they are not quite so easily manipulated and redistributed. I am told there is no copyright on the files, but it still seems polite to ask before using other people’s work, so please contact <[email protected]> for permission before asking us for text files. mSupply support also distributes mSupply software for inventory control, which has an inbuilt system for reporting on medicine usage using the ATC system You can download a full working version from www.msupply.org.nz Craig Drown, mSupply Support <[email protected]> April 2000 A (2-benzhydryloxyethyl)diethyl-methylammonium iodide A03AB16 0.3 g O 2-(4-chlorphenoxy)-ethanol D01AE06 4-dimethylaminophenol V03AB27 Abciximab B01AC13 25 mg P Absorbable gelatin sponge B02BC01 Acadesine C01EB13 Acamprosate V03AA03 2 g O Acarbose A10BF01 0.3 g O Acebutolol C07AB04 0.4 g O,P Acebutolol and thiazides C07BB04 Aceclidine S01EB08 Aceclidine, combinations S01EB58 Aceclofenac M01AB16 0.2 g O Acefylline piperazine R03DA09 Acemetacin M01AB11 Acenocoumarol B01AA07 5 mg O Acepromazine N05AA04 -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,821,928 B2 Hemmingsen Et Al

US008821928B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,821,928 B2 Hemmingsen et al. (45) Date of Patent: Sep. 2, 2014 (54) CONTROLLED RELEASE 5,869,097 A 2/1999 Wong et al. PHARMACEUTICAL COMPOSITIONS FOR 6,103,261 A 8, 2000 Chasin et al. 2003.01.18641 A1 6/2003 Maloney et al. PROLONGED EFFECT 2003/O133976 A1* 7/2003 Pather et al. .................. 424/466 2004/O151772 A1 8/2004 Andersen et al. (75) Inventors: Pernille Hoyrup Hemmingsen, 2005.0053655 A1 3/2005 Yang et al. Bagsvaerd (DK); Anders Vagno 2005/O158382 A1* 7/2005 Cruz et al. .................... 424/468 2006, O1939 12 A1 8, 2006 KetSela et al. Pedersen, Virum (DK); Daniel 2007/OOO3617 A1 1/2007 Fischer et al. Bar-Shalom, Kokkedal (DK) 2007,0004797 A1 1/2007 Weyers et al. (73) Assignee: Egalet Ltd., London (GB) 2007. O190142 A1 8, 2007 Breitenbach et al. (Continued) (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this patent is extended or adjusted under 35 FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS U.S.C. 154(b) by 1052 days. DE 202006O14131 1, 2007 EP O435,726 8, 1991 (21) Appl. No.: 12/602.953 (Continued) (22) PCT Filed: Jun. 4, 2008 OTHER PUBLICATIONS (86). PCT No.: PCT/EP2008/056910 Krogel etal (Pharmaceutical Research, vol. 15, 1998, pp. 474-481).* Notification of Transmittal of the International Search Report and the S371 (c)(1), Written Opinion of the International Searching Authority issued Jul. (2), (4) Date: Jun. 7, 2010 8, 2008 in International Application No. PCT/DK2008/000016. International Preliminary Reporton Patentability issued Jul. -

Prescription Medications, Drugs, Herbs & Chemicals Associated With

Prescription Medications, Drugs, Herbs & Chemicals Associated with Tinnitus American Tinnitus Association Prescription Medications, Drugs, Herbs & Chemicals Associated with Tinnitus All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form, or by any means, without the prior written permission of the American Tinnitus Association. ©2013 American Tinnitus Association Prescription Medications, Drugs, Herbs & Chemicals Associated with Tinnitus American Tinnitus Association This document is to be utilized as a conversation tool with your health care provider and is by no means a “complete” listing. Anyone reading this list of ototoxic drugs is strongly advised NOT to discontinue taking any prescribed medication without first contacting the prescribing physician. Just because a drug is listed does not mean that you will automatically get tinnitus, or exacerbate exisiting tinnitus, if you take it. A few will, but many will not. Whether or not you eperience tinnitus after taking one of the listed drugs or herbals, or after being exposed to one of the listed chemicals, depends on many factors ‐ such as your own body chemistry, your sensitivity to drugs, the dose you take, or the length of time you take the drug. It is important to note that there may be drugs NOT listed here that could still cause tinnitus. Although this list is one of the most complete listings of drugs associated with tinnitus, no list of this kind can ever be totally complete – therefore use it as a guide and resource, but do not take it as the final word. The drug brand name is italicized and is followed by the generic drug name in bold. -

Product Information Sheet

PURINES/PYRIMIDINES LIGAND-SET™ ProductInformation Product Number L2538 Storage Temperature -20°C Product Description The P2Y family is made up of 11 subtypes, P2Y1-11. The Purines/Pyrimidines LIGAND-SET™ is a set of 64 Each receptor binds to a single heterotrimeric G small organic ligands to the Adenosine and Purinergic protein, although the P2Y11 can couple to both Gq/11 and receptors. These ligands are arrayed in a standard 96- Gs. P2Y receptors do not form heteromultimeric well plate, format; each well has a capacity of 1 ml. assemblies with other P2Y subtypes, but many tissues show coexpression of subtypes (e.g., P2Y1 and P2Y2 This set can be used for screening new drug targets, for subpopulations in endothelial cells). The P2Y receptors guiding secondary screens of larger, more diverse show 25-55% homology at the amino acid level. libraries and for standardizing and validating new screening assays. Components/Reagents The Purines/Pyrimidines LIGAND-SET™ contains 2 mg Adenosine receptors are known to consist of four of each ligand per well. Stock solutions can be readily subtypes, A1, A2A, A2B and A3. The majority of the prepared by adding 1 ml of DMSO to each well. The known agonists are derivatives of adenosine. They are set also comes with a diskette containing a structural of interest as potential anti-arrhythmic, cerebro- database, or SD file and a Microsoft Excel file protective and cardioprotective agents via the A1 containing the catalog number, name, rack position and receptor and as hypotensive and antipsychotic agents pharmacological characteristics of each ligand. The via the A2A receptor. -

Minutes of PRAC Meeting of 05-08 March 2018

12 April 2018 EMA/288259/2018 Inspections, Human Medicines Pharmacovigilance and Committees Division Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) Minutes of the meeting on 05-08 March 2018 Chair: June Raine – Vice-Chair: Almath Spooner Health and safety information In accordance with the Agency’s health and safety policy, delegates were briefed on health, safety and emergency information and procedures prior to the start of the meeting. Disclaimers Some of the information contained in the minutes is considered commercially confidential or sensitive and therefore not disclosed. With regard to intended therapeutic indications or procedure scope listed against products, it must be noted that these may not reflect the full wording proposed by applicants and may also change during the course of the review. Additional details on some of these procedures will be published in the PRAC meeting highlights once the procedures are finalised. Of note, the minutes are a working document primarily designed for PRAC members and the work the Committee undertakes. Note on access to documents Some documents mentioned in the minutes cannot be released at present following a request for access to documents within the framework of Regulation (EC) No 1049/2001 as they are subject to on-going procedures for which a final decision has not yet been adopted. They will become public when adopted or considered public according to the principles stated in the Agency policy on access to documents (EMA/127362/2006, Rev. 1). 30 Churchill Place ● Canary Wharf ● London E14 5EU ● United Kingdom Telephone +44 (0)20 3660 6000 Facsimile +44 (0)20 3660 5520 Send a question via our website www.ema.europa.eu/contact An agency of the European Union © European Medicines Agency, 2018.