Birth of a Tree Farmer – Doug Stinson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOOKOUT NETWORK (ISSN 2154-4417), Is Published Quarterly by the Forest Fire Lookout Association, Inc., Keith Argow, Publisher, 374 Maple Nielsen

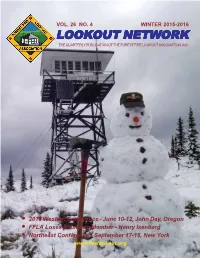

VOL. 26 NO. 4 WINTER 2015-2016 LLOOKOOKOUTOUT NETWNETWORKORK THE QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE FOREST FIRE LOOKOUT ASSOCIATION, INC. · 2016 Western Conference - June 10-12, John Day, Oregon · FFLA Loses Founding Member - Henry Isenberg · Northeast Conference - September 17-18, New York www.firelookout.org ON THE LOOKOUT From the National Chairman Keith A. Argow Vienna, Virginia Winter 2015-2016 FIRE TOWERS IN THE HEART OF DIXIE On Saturday, January 16 we convened the 26th annual member of the Alabama Forestry Commission who had meeting of the Forest Fire Lookout Association at the Talladega purchased and moved a fire tower to his woodlands; the project Ranger Station, on the Talladega National Forest in Talladega, leader of the Smith Mountain fire tower restoration; the publisher Alabama (guess that is somewhere near Talladega!). Our host, of a travel magazine that promoted the restoration; a retired District Ranger Gloria Nielsen, and Alabama National Forests district forester with the Alabama Forestry Commission; a U.S. Assistant Archaeologist Marcus Ridley presented a fine Forest Service District Ranger (our host), and a zone program including a review of the multi-year Horn Mountain archaeologist for the Forest Service. Add just two more Lookout restoration. A request by the radio communications members and we will have the makings of a potentially very people to construct a new effective chapter in Alabama. communications tower next to The rest of afternoon was spent with an inspection of the the lookout occasioned a continuing Horn Mountain Lookout restoration project, plus visits review on its impact on the 100-foot Horn Mountain Fire Tower, an historic landmark visible for many miles. -

A History of the Arôhitecture Of

United States Department of Agriculture A History of the I Forest Service Engineering Staff EM-731 0-8 Arôhitecture of the July 1999 USDA Forest Service a EM-731 0-8 C United States Department of Agriculture A History of the Forest Service EngIneering Staff EM-731 0-8 Architecture of the July 1999 USDA Forest Service by John A. Grosvenor, Architect Pacific Southwest Region Dedication and Acknowledgements This book is dedicated to all of those architects andbuilding designers who have provided the leadership and design expertise tothe USDA Forest Service building program from the inception of theagencyto Harry Kevich, my mentor and friend whoguided my career in the Forest Service, and especially to W. Ellis Groben, who provided the onlyprofessional architec- tural leadership from Washington. DC. I salute thearchaeologists, histori- ans, and historic preservation teamswho are active in preserving the architectural heritage of this unique organization. A special tribute goes to my wife, Caro, whohas supported all of my activi- ties these past 38 years in our marriage and in my careerwith the Forest Service. In the time it has taken me to compile this document, scoresof people throughout the Forest Service have provided information,photos, and drawings; told their stories; assisted In editing my writingattempts; and expressed support for this enormous effort. Active andretired architects from all the Forest Service Regions as well as severalof the research sta- tions have provided specific informationregarding their history. These individuals are too numerous to mention by namehere, but can be found throughout the document. I do want to mention the personwho is most responsible for my undertaking this task: Linda Lux,the Regional Historian in Region 5, who urged me to put somethingdown in writing before I retired. -

Fire Lookouts Eldorado National Forest

United States Department of Agriculture Fire Lookouts Eldorado National Forest Background Fire suppression became a national priority around 1910, when the country was stricken by what has been considered the largest wildfire in US history. The Big Blowup fire as it was called, burned over 3,000,000 acres (12,000 km) in Washington, Idaho, and Montana. After the Big Blowup, Fire Lookout towers were built across the country in hopes of preventing another “Blowup”. At this time Plummer Lookout. Can lookouts were primarily found in tall trees with rickety ladders and you see the 2 people? platforms or on high peaks with canvas tents for shelters. This job was not for the faint of heart. This did little to offer long‐term support for the much needed “Fire Watcher”, so by 1911 permanent cabins and cupolas were constructed on Mountain Ridges, Peaks, and tops. In California, between 1933 and 1942, Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) crews reportedly built 250 fire lookout towers. These crews also helped build access roads for the construction of these towers. Fire lookouts were at peak use from the 1930s through the 1950s. During World War II fire lookouts were assigned additional duties as Enemy Aircraft Spotters protecting the countries coastal lines and beaches. By the 1960s the Fire Lookouts were being used less frequently due to the rise in technology. Many lookouts were closed, or turned in to recreational facilities. Big Hill On the Eldorado ... Maintained and staffed 7 days a week The Eldorado Naonal Forest originally had 9 lookouts at the during fire season the Big Hill Lookout is beginning of the century. -

1933–1941, a New Deal for Forest Service Research in California

The Search for Forest Facts: A History of the Pacific Southwest Forest and Range Experiment Station, 1926–2000 Chapter 4: 1933–1941, A New Deal for Forest Service Research in California By the time President Franklin Delano Roosevelt won his landslide election in 1932, forest research in the United States had grown considerably from the early work of botanical explorers such as Andre Michaux and his classic Flora Boreali- Americana (Michaux 1803), which first revealed the Nation’s wealth and diversity of forest resources in 1803. Exploitation and rapid destruction of forest resources had led to the establishment of a federal Division of Forestry in 1876, and as the number of scientists professionally trained to manage and administer forest land grew in America, it became apparent that our knowledge of forestry was not entirely adequate. So, within 3 years after the reorganization of the Bureau of Forestry into the Forest Service in 1905, a series of experiment stations was estab- lished throughout the country. In 1915, a need for a continuing policy in forest research was recognized by the formation of the Branch of Research (BR) in the Forest Service—an action that paved the way for unified, nationwide attacks on the obvious and the obscure problems of American forestry. This idea developed into A National Program of Forest Research (Clapp 1926) that finally culminated in the McSweeney-McNary Forest Research Act (McSweeney-McNary Act) of 1928, which authorized a series of regional forest experiment stations and the undertaking of research in each of the major fields of forestry. Then on March 4, 1933, President Roosevelt was inaugurated, and during the “first hundred days” of Roosevelt’s administration, Congress passed his New Deal plan, putting the country on a better economic footing during a desperate time in the Nation’s history. -

Umatilla NF Recruitment Info Brochure.Indd

Seasonal Positions Available The Umatilla National Forest is seeking motivated individuals to fill natural resource and firefighting United States Department of Agriculture positions. These are federal positions that require hard work and dedication. A passion for the outdoors is required. RECRUITMENT INFORMATION Start Your Career Many career Forest Service employees started out as We will being accepting seasonal employees, this is how they “got their foot in applications from the door”. November 14 to Many firefighting jobs look for wildland fire experience November 20! and training. Each seasonal employee will have an opportunity to attend an on-the-job firefighter training. Setup your profile now on This training, called “Guard School”, is a one week school USAjobs.gov! covering the basics of wildland fire suppression, fire behavior, human factors, and the incident command system (S-130, S-190, S-110, I-100, L-180). Upon completion of “Guard School” the employee will be qualified to fight wildland fire as a Fire Fighter Type 2. Applying through USAJOBS Contact Informati on All applications must be submitted through usajobs.gov. htt ps://www.fs.usda.gov/main As with any online job site, the application process /umati lla/about-forest/jobs requires information about you that may not be readily www.facebook.com/Umati llaNF/ available. We recommend gathering information, creating a profile, and giving yourself ample time to Umati lla Nati onal Forest complete the application process. Applications must be Supervisor’s Offi ce 72510 Coyote Road submitted by the time indicated on the closing date. We Pendleton, OR 97801 are unable to accept late applications. -

LOOKOUT NETWORK (ISSN 2154-4417), Is Published Quarterly by the ($6.85 + S/H)

VOL. 22 NO. 2 SUMMER 2011 LLOOKOOKOUTOUT NETWNETWORKORK THE QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE FOREST FIRE LOOKOUT ASSOCIATION, INC. · Western Conference - Mt Hood, Oregon September 16-18 · Boucher Hill Coming to Life Soon · Historic Maine Lookout Lost www.firelookout.org ON THE LOOKOUT From the National Chairman Keith A. Argow Vienna, Virginia Summer 2011 WEAR YOUR FIRE LOOKOUT BADGE PROUDLY! IT EXPRESSES BOTH YOUR COMMITMENT AND THE on duty is an employee. Yet of the 12 active lookouts in OPPORTUNITY FOR OTHERS TO SERVE Southern California, only one is staffed by a paid lookout. Our communal efforts and hard work to protect fire YOUR CHANCE TO HAND OUT A FFLA BROCHURE! lookouts comes from a love of these vintage structures as well When folks see these badges with the distinctive FFLA as our enjoyment of the beautiful views they afford. We also logo, they are likely to ask about our association. Voila! Here appreciate the trees and forests they were built to protect. Most is the opportunity to present them with the FFLA brochure! Let of us have spent time as a volunteer or paid fire lookout them know how they can become involved in either observer. Those who haven't had this opportunity likely harbor maintenance or staffing as a volunteer. A select few will even the dream that they may one day wear this badge of honor. If adopt a favorite lookout as the Lookout Steward by making not, at the very least they know they have helped keep these application through their state director, with the approval of the symbols of forestry up on the skyline for future generations of agency confirmed by the national chair. -

Oral History Interview with June Ash and Gordon Ash, November 1, 2016

Archives and Special Collections Mansfield Library, University of Montana Missoula MT 59812-9936 Email: [email protected] Telephone: (406) 243-2053 The transcript with its associated audio recording was provided to Archives and Special Collections by the Northwest Montana Lookout Association. Oral History Number: 453-003 Interviewee: June Ash and Gordon Ash Interviewer: Beth Hodder Date of Interview: November 1, 2016 Project: Northwest Montana Lookout Association Oral History Project I'm Beth Hodder (BH). I'm here with June Ash (JA) and her son, Gordon Ash (GA). June and her husband, Rod, were lookouts, and I am here to interview June to ask stories about what you and Rod did while up there and anything else that seems to be relevant to the time. The interview’s being conducted by the Northwest Montana Forest Fire Lookout Association, of which I am a part. BH: June, where were you a lookout? JA: We were on Big Swede in Libby, Montana. We worked for the Kootenai National Forest. We both were college students from the University of California at Berkley. Rod was doing research for his masters, and he wanted to do a little book reading and research. We thought, well, how could we maximize and make a little money at the same time? So, we applied with the Forest Service for the lookout job in the year1952. We left Berkley and drove north and arrived in Libby, Montana for the summer, and worked on Big Swede. It was a pretty exciting experience for us, because Big Swede was a very popular lookout. -

National Park Service Fire Management Careers

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior National Interagency Fire Center Idaho National Park Service Fire Management Careers Looking for a job and/or a career which combines love of the land, science and technology skills, leadership and people skills? Then you may be the right person for a job or career in Fire Management in the National Park Service. There are many different specializations in the Smokejumper: Specialized, experienced NPS Fire Management Program, some of which firefighter who works as a team with other require special skills and training, and all of smokejumpers, parachuting into remote areas for which require enthusiasm and dedica tion. This initial attack on wildland fires. is a competitive arena which places physical and mental demands on employees. Helitack Crewmember: Serves as initial attack firefighter and support for helicopter opera tions Employees are hired for temporary and per on large fires. manent jobs, year round depending upon the area of the country. As an employee’s compe Fire Use Module Member: Serves as a crew tencies and skills develop, their opportunities to member working on prescribed fire, fuels advance in fire management increases. reduction projects, and fires that are managed for resource benefits. Positions Available Firefighter: Serves as a crewmember on a Dispatcher: Serves as central coordinator for handcrew, using a variety of specialized tools, relaying information regarding a fire as well as equipment, and techniques on wildland and pre ordering personnel and equipment. scribed fires. Job announcements for firefighter Fire Lookout: Serves as locator for fires in remote positions may be titled as Forestry Technician or locations and informs emergency response Range Technician. -

FY21 Authorized and Funded LRF Deferred Maintenance Projects

FY21 Authorized and Funded LRF Deferred Maintenance Projects Forest or Region State Cong. District Asset Type Project Description Grassland Project Name This project proposes improvements along the Westfork Bike Trail, including the addition of West Fork San Gabriel Accessible Recreation Site, ABA/ADA compliant fishing platforms, minor road maintenance (designated as National Scenic R05 Angeles CA CA-27 Fishing Opportunities Trail, Road Bikeway), striping of picnic area/overflow parking, and signs. An existing agreement with the National Forest Foundation will provide a match. Other partners have submitted grant proposals. This project will complete unfunded items, including the replacement of picnic tables, fencing Recreation Site, R05 Cleveland Renovate Laguna Campground CA CA-50 entrance gates, signage, and infrastructure. The campground renovation project is substantially Trail funded by external agreement. The project is within USDA designated Laguna Recreation Area, This project will enhance equestrian access by improving of traffic flow/control and improving ADA parking to complete campground renovation project including restroom restoration and Recreation Site, decommissioning of old camp spurs, partially funded by external agreements. The Pacific Crest R05 Cleveland Renovate Boulder Oaks Campground CA CA-51 Trail Trail runs through this campground and is a key location for hikers to camp. It is the only equestrian campground located on section A of Pacific Crest Trail. This project is key for threatened and endangered species habitat and cultural site management. This project will repave the access road, conduct site improvements, replace barriers, replace fire Recreation Site, R05 Cleveland Renovate El Cariso Campground CA CA-42 rings and tables, and replace trash receptacles. -

After the Burn Assessing and Managing Your Forestland After a Wildfi Re Station Bulletin No

After the Burn Assessing and Managing Your Forestland After a Wildfi re Station Bulletin No. 76 August, 2006 By Yvonne C. Barkley Idaho Forest, Wildlife and Range Experiment Station Moscow, Idaho Director Steven B. Daley Laursen Acknowledgements After the Burn was written by Yvonne C. Barkley, Associate Extension Forester, University of Idaho Extension. Special thanks to the following people for their professional review of this publication: Steve Cook, Associate Professor - Forest Entomology, University of Idaho, Moscow, ID Deb Dumroese, Research Soil Scientist: Project Leader, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Moscow, ID Gregg DeNitto, Forest Health Protection: Group Leader, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Missoula, MT Dennis Ferguson, Research Scientist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Moscow, ID Mary Fritz, Private Forestry Specialist, Idaho Department of Lands, Orofi no, ID Frank Gariglio, State Forester, Natural Resource Conservation Service, Lewiston, ID Nick Gerhardt, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Nez Perce National Forest, Grangeville, ID Terrie Jain, Silviculturist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Moscow, ID Tim Kennedy, Private Forestry Specialist, Idaho Department of Lands, Boise, ID Brian Kummet, Fee Lands Forester, Nez Perce Tribal Forestry, Lapwai, ID Ron Mahoney, Professor and Extension Forester, University of Idaho, Moscow, ID Marci Nielsen-Gerhardt, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Nez Perce National Forest, Grangeville, ID Jeff Olson, Associate Director, Publications, University Communications & Marketing, University of Idaho, Mosocw, ID Kerry Overton, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Boise, ID David Powell, Silviculturist, U.S. -

A Study of Historic Fire Towers and Lookout Life in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park Laura Beth Ingle Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2011 Every Day Is Fire Day: A Study of Historic Fire Towers and Lookout Life in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park Laura Beth Ingle Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ingle, Laura Beth, "Every Day Is Fire Day: A Study of Historic Fire Towers and Lookout Life in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park" (2011). All Theses. 1130. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1130 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVERY DAY IS FIRE DAY: A STUDY OF HISTORIC FIRE TOWERS AND LOOKOUT LIFE IN THE GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Schools of Clemson University and the College of Charleston In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Historic Preservation by Laura Beth Ingle May 2011 Accepted by: Ashley Robbins Wilson, Committee Chair Barry Stiefel, Ph.D. James Liphus Ward ABSTRACT When the Great Smoky Mountains National Park (GRSM) was established in 1931, complete fire suppression was the fire management philosophy and goal in all national parks and forests across the country. Debris and undergrowth was cleared, fire breaks and manways were created, and thousands of fire towers were constructed. The young men of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) provided much of the manpower to complete these tasks, and the group’s signature rustic style left its mark on structures throughout the park. -

Green Mountain Fire Lookout Relocation

NOTICE OF AVAILABILITY ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT (EA #OR-010-2004-05) AND FINDING OF NO SIGNIFICANT IMPACT (FONSI) FOR GREEN MOUNTAIN LOOKOUT The Bureau of Land Management, Lakeview District, has analyzed a proposal and several alternatives to replace the existing fire lookout facility located on Green Mountain in northern Lake County, Oregon. An EA and FONSI have been prepared to document the potential impacts of the proposed action. Copies of the documents are available for review by writing to the Lakeview District Office, 1301 South G Street, Lakeview, Oregon 97630, or by calling Bob Crumrine or Paul Whitman at (541) 947-2177. The documents are also available on the BLM‟s website at http://www.blm.gov/or/districts/lakeview/plans/index.php. Those wishing to provide comments on the proposal must do so, in writing, by May 14, 2009. FINDING OF NO SIGNIFICANT IMPACT Green Mountain Lookout EA# OR-OIO-2004-05 The Bureau of Land Management, Lakeview District, has analyzed a proposal and several alternatives to replace the existing fire lookout facility located on Green Mountain in north Lake County, Oregon. The new lookout would include water and shower systems, security systems, heating, bathroom, structure improvements, fire-finders, and interior furnishings. The alternatives vary in the amount ofnew access road or road realignment work that would be required. The proposed project is in conformance with applicable land use plans and policies. There are no flood plains, wetlands, riparian areas, water quality, fish or aquatic habitat, threatened, endangered, special status or sensitive species, prime or unique farmlands, wild and scenic rivers, areas ofcritical environmental concern, research natural areas, designated wilderness, wilderness study areas, or other lands with wilderness characteristics, or wild horses in the project area.