Decomposing Capitalism Socialists in Power, Iceland 1956-1958

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

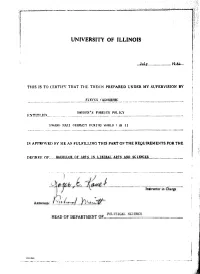

University of Illinois

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS ...M* ... .................... THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY STEVEN I'AXON’BERC SWEDEN'S FOREIGN POLICY ENTITLED. TOWARD NAZI GERMANY DURING WORLD VAR II IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF..... .......................................................................................... ............................. O 1 - J M SWEDEN'S FOREIGN POLICY TOWARD NAZI GERMANY DURING WORLD WAR II BY STEVEN SAXONBERG THESIS for the DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS IN LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES College of Liberal Arts and Sciences University of Illinois Urbane, Illinois i 1984 INTRODUCTION Sweden's foreign policy toward Nazi Germany during World War Two makes for an Interesting case study because the country faced so many dllemas. The coun try's foreign policy makers tad to answer questions such as: Can Sweden afford to be neutral at a time when a ruthless dictator threatened all of Europe and who. If successful In his war, would undoubtably attack Sweden sooner or later? What price should Sweden be willing to pay to stay out of the war In the face of German demands which Infringe upon a "strict neutrality"? Is 1t morally justifiable to make concessions to Germany which contribute to Its war drive, such as Its occupation of Norway, In order to avoid German reprisals? This paper will examine the manner In which Swedish forelgh policy makers dealt with the above questions. In addition, the goals behind Sweden's neutral ity polity will be examined, as well as theories of how Sweden avoided the war. They provide the framework 1n which the foreign policy makers tad to work. -

Danish Cold War Historiography

SURVEY ARTICLE Danish Cold War Historiography ✣ Rasmus Mariager This article reviews the scholarly debate that has developed since the 1970s on Denmark and the Cold War. Over the past three decades, Danish Cold War historiography has reached a volume and standard that merits international attention. Until the 1970s, almost no archive-based research had been con- ducted on Denmark and the Cold War. Beginning in the late 1970s, however, historians and political scientists began to assess Danish Cold War history. By the time an encyclopedia on Denmark and the Cold War was published in 2011, it included some 400 entries written by 70 researchers, the majority of them established scholars.1 The expanding body of literature has shown that Danish Cold War pol- icy possessed characteristics that were generally applicable, particularly with regard to alliance policy. As a small frontline state that shared naval borders with East Germany and Poland, Denmark found itself in a difficult situation in relation to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) as well as the Soviet Union. With regard to NATO, Danish policymakers balanced policies of integration and screening. The Danish government had to assure the Soviet Union of Denmark’s and NATO’s peaceful intentions even as Denmark and NATO concurrently rearmed. The balancing act was not easily managed. A review of Danish Cold War historiography also has relevance for con- temporary developments within Danish politics and research. Over the past quarter century, Danish Cold War history has been remarkably politicized.2 The end of the Cold War has seen the successive publication of reports and white books on Danish Cold War history commissioned by the Dan- ish government. -

Uppbrott Från Stalinismen – Till En Socialism Med Mänskligt Ansikte Tidens Förlag 1973

Sven Landin Uppbrott från stalinismen – till en socialism med mänskligt ansikte Tidens förlag 1973 1962 råkade det svenska kommunistpartiet (SKP, senare VPK) ut för ett svidande valnederlag (3,5% av rösterna), vilket skärpte den olust och kritik som funnits i partiet sedan början av 1950-talet. Detta ledde till ideologiska och politiska motsättningar och en intensiv debatt, särskilt inför SKP:s 20:e partikongress. Flera grupperingar formerades och tog till orda, bland annat en gammelkommunistisk riktning (med bl a gamle ordföranden Hilding Hagberg), en mer nyvästerinriktad tendens (blivande ordföranden C H Hermansson), maoister (Nils Holm- berg), titoister (Sven Landin) m fl mer svårplacerade riktningar. Om detta, se samlingen Debatt i svenska kommunistpartiet (SKP) 1962-63, som presenterar de olika grupperingar- na/debattörerna tillsammans med ett representativt urval debattinlägg, samt ger ytterligare tips med artiklar och böcker om kommunistpartiets utveckling under dessa år (de flesta av dem finns på marxistarkivet). Flera av de riktningar/tendenser som gav sig till känna under debatten skulle senare bryta med eller lämna partiet. En del av dem gick 1968 (året för Sovjets invasion av Tjeckoslovakien) över till socialdemokratin, bland dem Anton Strand och Sven Landin, författare av denna uppgörelse med SKP/VPK (som kom ut 1973, dvs flera år efter han lämnat partiet). Anton Strand skrev också en bok: Röd Front – En debattbok om de svenska kommunisternas program och praktiska politik. Den kom dock ut redan 1967, då författaren fortfarande var medlem i kommunistpartiet. Strands bok har därför också en annan karaktär än Landins: medan Röd front är en ”debattbok”, är Uppbrott… ett slags brytningsdokument, en mer övergripande ideologisk-politisk uppgörelse med SKP/VPK. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/113675 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-10-04 and may be subject to change. SWEDISH NEUTRALITY AND THE COLD WAR, 1945 -1949. Gerard Aalders SWEDISHNEUTRALITYANDTHE COLD WAR, 1945-194 9. Gerard Aalders Amsterdam 1989 SWEDISH NEUTRALITY AND THE COLD WAR, 1945-194 9. Een politicologisch-historische studie Een wetenschappelijke proeve op het gebied van de Beleidswetenschappen. Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Katholieke Universiteit van Nijmegen, volgens besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op maandag 2 October 1989 des namiddags te 1.30 uur door Gerhardus Hendrik Aalders geboren op 14 maart 1946 te Hellendoom. Promotor Prof. Dr. Göran Therborn Universiteit van Gotenburg, Zweden SWEDISH NEUTRALITY AND THE COLD WAR, 1945 -1949. Acknowledgements Introduction 1 a. Neutrality and Swedish neutrality 2 b. Neutrality and World War 11 7 с The Cold War 11 d. The period 1945-1949 13 e. Problems to be discussed 15 1. The United Nations Membership 17 1.1 The League of Nations Debate 17 1.2 The UN debate 19 2. Between East and West. The credit- and tradeagreement with Russia 25 2.1 History and background 25 2.2 The terms of the Ryssavtalet 28 2.3 Swedish political and press debates on the Ryssavtalet 29 2.4 The industry and Ryssavtalet 34 2.5 The American protest note 40 2.6 The failure of the credit 43 3. -

Nordic Narratives of the Second World War : National Historiographies Revisited

Nordic Narratives of the Second World War : National Historiographies Revisited Stenius, Henrik; Österberg, Mirja; Östling, Johan 2011 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Stenius, H., Österberg, M., & Östling, J. (Eds.) (2011). Nordic Narratives of the Second World War : National Historiographies Revisited. Nordic Academic Press. Total number of authors: 3 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 nordic narratives of the second world war Nordic Narratives of the Second World War National Historiographies Revisited Henrik Stenius, Mirja Österberg & Johan Östling (eds.) nordic academic press Nordic Academic Press P.O. Box 1206 SE-221 05 Lund, Sweden [email protected] www.nordicacademicpress.com © Nordic Academic Press and the authors 2011 Typesetting: Frederic Täckström www.sbmolle.com Cover: Jacob Wiberg Cover image: Scene from the Danish movie Flammen & Citronen, 2008. -

Övervakningen Av ”SKP-Komplexet”

Förord Säkerhetstjänstkommissionen tillkom vid en tidpunkt då olika for- skare, framför allt historiker och statsvetare, inlett arbeten med projekt som låg nära kommissionens uppdrag. Flera av dessa pro- jekt hade påbörjats inom ramen för det forskningsprogram om svensk militär underrättelse- och säkerhetstjänst som Humanistisk- samhällsvetenskapliga forskningsrådet på regeringens uppdrag ut- lyst i februari 1998. Genom att anställa några av forskarna som ex- perter kunde kommissionen tillgodogöra sig deras kunskaper och kompetens och ge dem möjlighet att arbeta med fri tillgång till det relevanta källmaterialet. Resultatet av deras arbete publiceras som bilagor till kommissionens betänkande. Rapporterna har föredra- gits för och diskuterats i kommissionen. Författarna svarar dock själva för sakinnehållet. Det är med andra ord respektive författares analyser, tolkningar och slutsatser som presenteras i rapporterna. Vidare publiceras som bilagor till kommissionens betänkande ett antal rapporter som författats inom kommissionens sekretariat och av enskilda kommissionsledamöter. Gunnar Brodin Ordförande i Säkerhetstjänstkommissionen SOU 2002:93 Övervakningen av ”SKP-komplexet” Innehåll 1 Introduktion.................................................................5 2 SKP - utveckling, hotbild och övervakning före 1945 .......9 2.1 SKP – sektion av Kommunistiska Internationalen ..................9 2.2 Hotbilden före 1945.................................................................11 2.2.1 Mellankrigstiden............................................................11 -

Rikets Säkerhet Och Den Personliga Integriteten. De Svenska Säkerhets- Tjänsternas Författningsskyddande Verksamhet Sedan År 1945

Till statsrådet och chefen för Justitiedepartementet Regeringen beslutade den 25 mars 1999 att tillkalla en kommission med uppgift att kartlägga och granska den författningsskyddande verksamhet som de svenska säkerhetstjänsterna bedrivit när det gäller hot som härrör ur inrikes förhållanden. Kommissionen be- står, enligt direktiv 1999:26 och tilläggsdirektiv 1999:59, av en ord- förande och fem ledamöter. Som ordförande i kommissionen förordnades fr.o.m. den 25 mars 1999 riksmarskalken Gunnar Brodin och som ledamöter fr.o.m. den 21 maj 1999 f.d. justitierådet Anders Knutsson, general- sekreteraren i Frivilligorganisationernas fond för mänskliga rättig- heter Anita Klum och journalisten Ewonne Winblad samt fr.o.m. den 1 augusti 1999 professor Alf W Johansson och professor Karl Molin. Som sakkunnig med uppgift att biträda vid granskningen av be- tänkandet från sekretessynpunkt förordnades fr.o.m. den 5 augusti 2002 justitierådet Göran Regner. Som experter har varit förordnade generalmajor Erik Rossander (den 6 december 1999 - den 30 april 2001), f.d. kanslichefen vid Försvarets underrättelsenämnd Sören Nilsson (den 1 januari 2000 - den 28 februari 2001), f.d. byråchefen vid säkerhetspolisen Olav Robertsson (den 1 januari 2000 - den 30 april 2001), fil.kand. Mag- nus Hjort (den 13 mars 2000 - den 28 februari 2001), professor Ulf Bjereld (den 1 september 2000 - den 28 februari 2001), docent Klaus Richard Böhme (den 1 september 2000 - den 28 februari 2001), fil.kand. Ulf Eliasson (den 1 september 2000 - den 28 febru- ari 2001), fil.dr Thomas Jonter (den 1 september 2000 - den 28 feb- ruari 2001), fil.dr Werner Schmidt (den 1 september 2000 - den 31 mars 2001), arkivrådet Evabritta Wallberg (den 1 september 2000 - den 28 februari 2001), professor Kent Zetterberg (den 1 september 2000 - den 30 november 2000) och fil.dr Jacob Gustavsson (den 1 - 30 november 2000). -

Socialistiska Partiet 1929-1937

Bernt Kennerström Mellan två internationaler Socialistiska Partiet 1929-37 Arkiv avhandlingsserie 2 Copyright Bernt Kennerström (1974) Kristianstad 1980 Avhandlingen digitaliserad med författarens tillstånd Boken finns fortfarande tillgänglig på förlaget (Arkiv) och kan köpas direkt därifrån Innehåll Inledning..................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Sprängningen av Sverges Kommunistiska Parti 1929 ........................................................... 3 Uppkomsten av en partiopposition: antikrigskampanjen....................................................... 4 Förhållandet till socialdemokratin.......................................................................................... 5 Partioppositionens konsolidering ........................................................................................... 6 Partistriden efter Kominterns kongress: riksdagsvalet och avrustningsfrågan ...................... 7 Den fackliga politiken ............................................................................................................ 8 LO-ledningens motoffensiv.................................................................................................. 10 Exekutivkommitténs ingripande i partistriden ..................................................................... 12 Partiets sprängning ............................................................................................................... 14 2. Partiorganisation -

How East Germany Operated in Scandinavian Countries 1958–1989

Bertil Häggman: How East Germany Operated in Scandinavia 95 How East Germany Operated in Scandinavian Countries 1958–1989 Intelligence, Party Contacts, Schooling and Active Measures1 Bertil Häggman In September 1999 the East German Staatssicherheitsdienst (Stasi) or Ministerium für Staatssicherheit (Ministry for State Security, MfS) featured prominently in the headlines as former Stasi agents in Great Britain were exposed. The MfS had been created in 1950 and was not disbanded until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. It was responsible for both domestic surveillance and for foreign espionage. At the height of its power it employed 85,000 full-time officers as well as several hundred thousand informers, who assembled records on five million citizens – one third of the entire population. The files of the Stasi, if put in line, would cover more than 100 miles. According to Mark Almond, lecturer in modern history at Oxford University, the Stasi assessed every student or researcher from the West who spent time in East Germany.2 ‘Somebody who worked in a university for instance, might after all teach somebody who went into politics, went into the army or was a scientist who could be valuable, not just to the East German Stasi, but for all the former communist bloc secret services,’ so Almond. But in the strategy perfected by Markus Wolf, who headed the Hauptver- waltung Aufklärung (HV A), the foreign espionage branch, foreigners recruited for the Stasi were steered toward jobs in the heart of western governments or in the European Union or NATO. -

Den Farliga Fredsrörelsen – Säkerhetstjänsternas Övervakning

Förord Säkerhetstjänstkommissionen tillkom vid en tidpunkt då olika for- skare, framför allt historiker och statsvetare, inlett arbeten med projekt som låg nära kommissionens uppdrag. Flera av dessa pro- jekt hade påbörjats inom ramen för det forskningsprogram om svensk militär underrättelse- och säkerhetstjänst som Humanistisk- samhällsvetenskapliga forskningsrådet på regeringens uppdrag ut- lyst i februari 1998. Genom att anställa några av forskarna som ex- perter kunde kommissionen tillgodogöra sig deras kunskaper och kompetens och ge dem möjlighet att arbeta med fri tillgång till det relevanta källmaterialet. Resultatet av deras arbete publiceras som bilagor till kommissionens betänkande. Rapporterna har föredra- gits för och diskuterats i kommissionen. Författarna svarar dock själva för sakinnehållet. Det är med andra ord respektive författares analyser, tolkningar och slutsatser som presenteras i rapporterna. Vidare publiceras som bilagor till kommissionens betänkande ett antal rapporter som författats inom kommissionens sekretariat och av enskilda kommissionsledamöter. Gunnar Brodin Ordförande i Säkerhetstjänstkommissionen Innehåll 1 Inledning ......................................................................11 Bakgrund............................................................................................11 Forskningsuppgiften .........................................................................12 Källmaterialet.....................................................................................16 Disposition.........................................................................................18 -

Anti-Fascism in a Global Perspective

ANTI-FASCISM IN A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE Transnational Networks, Exile Communities, and Radical Internationalism Edited by Kasper Braskén, Nigel Copsey and David Featherstone First published 2021 ISBN: 978-1-138-35218-6 (hbk) ISBN: 978-1-138-35219-3 (pbk) ISBN: 978-0-429-05835-6 (ebk) Chapter 5 ‘Make Scandinavia a bulwark against fascism!’: Hitler’s seizure of power and the transnational anti-fascist movement in the Nordic countries Kasper Braskén (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) This OA chapter is funded by the Academy of Finland (project number 309624) 5 ‘MAKE SCANDINAVIA A BULWARK AGAINST FASCISM!’ Hitler’s seizure of power and the transnational anti-fascist movement in the Nordic countries Kasper Braskén On a global scale, Hitler’s seizure of power on 30 January 1933 provided urgent impetus for transnational anti-fascist conferences and rallies. One of the first Eur- opean, but almost completely overlooked major conferences was organised in Copenhagen in mid-April 1933 in the form of a Scandinavian Anti-Fascist Con- ference. This formed a transnational meeting point of European and especially Scandinavian workers and intellectuals that provided an important first response to developments in Germany. The chapter will use the Scandinavian conference as a prism to look back at anti-fascist activism in the Nordic countries during the preceding years, and to then follow its transformation after 1933. It will contribute to the global analysis of the transition period of communist-led anti-fascism from the sectarian class-against-class line to the inception of the popular front period in 1935. What were these largely overlooked, first anti-fascist articulations in Europe, and how were they connected to the rising transnational and global anti-fascist mobi- lisation coordinated in Paris and London? As we shall see, on the one hand Hitler’s seizure of power vitalised anti-fascism in Scandinavia but paradoxically, on the other, it further sharpened the communist critique of reformist social democracy and empowered social democratic anti-communism. -

Mmubn000001 080482082.Pdf

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/113675 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-10-06 and may be subject to change. SWEDISH NEUTRALITY AND THE COLD WAR, 1945 -1949. Gerard Aalders SWEDISHNEUTRALITYANDTHE COLD WAR, 1945-194 9. Gerard Aalders Amsterdam 1989 SWEDISH NEUTRALITY AND THE COLD WAR, 1945-194 9. Een politicologisch-historische studie Een wetenschappelijke proeve op het gebied van de Beleidswetenschappen. Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Katholieke Universiteit van Nijmegen, volgens besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op maandag 2 October 1989 des namiddags te 1.30 uur door Gerhardus Hendrik Aalders geboren op 14 maart 1946 te Hellendoom. Promotor Prof. Dr. Göran Therborn Universiteit van Gotenburg, Zweden SWEDISH NEUTRALITY AND THE COLD WAR, 1945 -1949. Acknowledgements Introduction 1 a. Neutrality and Swedish neutrality 2 b. Neutrality and World War 11 7 с The Cold War 11 d. The period 1945-1949 13 e. Problems to be discussed 15 1. The United Nations Membership 17 1.1 The League of Nations Debate 17 1.2 The UN debate 19 2. Between East and West. The credit- and tradeagreement with Russia 25 2.1 History and background 25 2.2 The terms of the Ryssavtalet 28 2.3 Swedish political and press debates on the Ryssavtalet 29 2.4 The industry and Ryssavtalet 34 2.5 The American protest note 40 2.6 The failure of the credit 43 3.