Mapping Trans-National Alt-Right

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Classification Decision for the Great

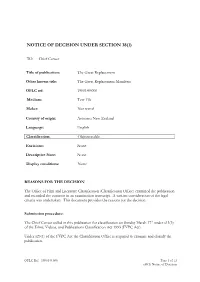

NOTICE OF DECISION UNDER SECTION 38(1) TO: Chief Censor Title of publication: The Great Replacement Other known title: The Great Replacement Manifesto OFLC ref: 1900149.000 Medium: Text File Maker: Not stated Country of origin: Aotearoa New Zealand Language: English Classification: Objectionable. Excisions: None Descriptive Note: None Display conditions: None REASONS FOR THE DECISION The Office of Film and Literature Classification (Classification Office) examined the publication and recorded the contents in an examination transcript. A written consideration of the legal criteria was undertaken. This document provides the reasons for the decision. Submission procedure: The Chief Censor called in this publication for classification on Sunday March 17th under s13(3) of the Films, Videos, and Publications Classification Act 1993 (FVPC Act). Under s23(1) of the FVPC Act the Classification Office is required to examine and classify the publication. OFLC Ref: 1900149.000 Page 1 of 13 s38(1) Notice of Decision Under s23(2) of the FVPC Act the Classification Office must determine whether the publication is to be classified as unrestricted, objectionable, or objectionable except in particular circumstances. Section 23(3) permits the Classification Office to restrict a publication that would otherwise be classified as objectionable so that it can be made available to particular persons or classes of persons for educational, professional, scientific, literary, artistic, or technical purposes. Synopsis of written submission(s): No submissions were required or sought in relation to the classification of the text. Submissions are not required in cases where the Chief Censor has exercised his authority to call in a publication for examination under section 13(3) of the FVPC Act. -

Chapter 4 the Right-Wing Media Enablers of Anti-Islam Propaganda

Chapter 4 The right-wing media enablers of anti-Islam propaganda Spreading anti-Muslim hate in America depends on a well-developed right-wing media echo chamber to amplify a few marginal voices. The think tank misinforma- tion experts and grassroots and religious-right organizations profiled in this report boast a symbiotic relationship with a loosely aligned, ideologically-akin group of right-wing blogs, magazines, radio stations, newspapers, and television news shows to spread their anti-Islam messages and myths. The media outlets, in turn, give members of this network the exposure needed to amplify their message, reach larger audiences, drive fundraising numbers, and grow their membership base. Some well-established conservative media outlets are a key part of this echo cham- ber, mixing coverage of alarmist threats posed by the mere existence of Muslims in America with other news stories. Chief among the media partners are the Fox News empire,1 the influential conservative magazine National Review and its website,2 a host of right-wing radio hosts, The Washington Times newspaper and website,3 and the Christian Broadcasting Network and website.4 They tout Frank Gaffney, David Yerushalmi, Daniel Pipes, Robert Spencer, Steven Emerson, and others as experts, and invite supposedly moderate Muslim and Arabs to endorse bigoted views. In so doing, these media organizations amplify harm- ful, anti-Muslim views to wide audiences. (See box on page 86) In this chapter we profile some of the right-wing media enablers, beginning with the websites, then hate radio, then the television outlets. The websites A network of right-wing websites and blogs are frequently the primary movers of anti-Muslim messages and myths. -

The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right Josh Vandiver Ball State University Various source media, Political Extremism and Radicalism in the Twentieth Century EMPOWER™ RESEARCH The radical political movement known as the Alt-Right Revolution, and Evolian Traditionalism – for an is, without question, a twenty-first century American audience. phenomenon.1 As the hipster-esque ‘alt’ prefix 3. A refined and intensified gender politics, a suggests, the movement aspires to offer a youthful form of ‘ultra-masculinism.’ alternative to conservatism or the Establishment Right, a clean break and a fresh start for the new century and .2 the Millennial and ‘Z’ generations While the first has long been a feature of American political life (albeit a highly marginal one), and the second has been paralleled elsewhere on the Unlike earlier radical right movements, the Alt-Right transnational right, together the three make for an operates natively within the political medium of late unusual fusion. modernity – cyberspace – because it emerged within that medium and has been continuously shaped by its ongoing development. This operational innovation will Seminal Alt-Right figures, such as Andrew Anglin,4 continue to have far-reaching and unpredictable Richard Spencer,5 and Greg Johnson,6 have been active effects, but researchers should take care to precisely for less than a decade. While none has continuously delineate the Alt-Right’s broader uniqueness. designated the movement as ‘Alt-Right’ (including Investigating the Alt-Right’s incipient ideology – the Spencer, who coined the term), each has consistently ferment of political discourses, images, and ideas with returned to it as demarcating the ideological territory which it seeks to define itself – one finds numerous they share. -

Democracy and Dissent: Strauss, Arendt, and Voegelin in America

Denver Law Review Volume 89 Issue 3 Special Issue - Constitutionalism and Article 6 Revolutions December 2020 Democracy and Dissent: Strauss, Arendt, and Voegelin in America Stephen M. Feldman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/dlr Recommended Citation Stephen M. Feldman, Democracy and Dissent: Strauss, Arendt, and Voegelin in America, 89 Denv. U. L. Rev. 671 (2012). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. DEMOCRACY AND DISSENT: STRAUSS, ARENDT, AND VOEGELIN IN AMERICA STEPHEN M. FELDMANt During the 1930s, American democratic government underwent a paradigmatic transformation.' From the framing through the 1920s, the United States operated as a republican democracy. Citizens and elected officials were supposed to be virtuous: in the political realm, they were to pursue the common good or public welfare rather than their own "par- tial or private interests."2 Intellectually, republican democracy had premodern roots stretching back to antiquity. 3 As such, republican demo- cratic theorists often conceptualized the common good in objectivist terms, as if there existed a distinct good that could be clearly ascer- tained.4 Equally important, for at least a century, republican democracy seemed to fit the agrarian, rural, and relatively homogenous American society. Thomas Jefferson, for one, insisted that the agrarian economy and widespread rural land ownership promoted a virtuous commitment to the common good.5 And given that, in the nation's early decades, an overwhelming number of Americans were Protestants who traced their ancestry to Western or Northern Europe, the people seemed sufficiently homogeneous to join together in the pursuit of the common good.6 Of course, some Americans did not fit the mold. -

How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics

GETTY CORUM IMAGES/SAMUEL How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics By Simon Clark July 2020 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics By Simon Clark July 2020 Contents 1 Introduction and summary 4 Tracing the origins of white supremacist ideas 13 How did this start, and how can it end? 16 Conclusion 17 About the author and acknowledgments 18 Endnotes Introduction and summary The United States is living through a moment of profound and positive change in attitudes toward race, with a large majority of citizens1 coming to grips with the deeply embedded historical legacy of racist structures and ideas. The recent protests and public reaction to George Floyd’s murder are a testament to many individu- als’ deep commitment to renewing the founding ideals of the republic. But there is another, more dangerous, side to this debate—one that seeks to rehabilitate toxic political notions of racial superiority, stokes fear of immigrants and minorities to inflame grievances for political ends, and attempts to build a notion of an embat- tled white majority which has to defend its power by any means necessary. These notions, once the preserve of fringe white nationalist groups, have increasingly infiltrated the mainstream of American political and cultural discussion, with poi- sonous results. For a starting point, one must look no further than President Donald Trump’s senior adviser for policy and chief speechwriter, Stephen Miller. In December 2019, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Hatewatch published a cache of more than 900 emails2 Miller wrote to his contacts at Breitbart News before the 2016 presidential election. -

Democratic Vanguardism

Democratic Vanguardism Modernity, Intervention, and the making of the Bush Doctrine Michael Harland A Thesis Submitted in Fulfillment of The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Department of History University of Canterbury 2013 For Francine Contents Acknowledgements 1 Abstract 3 Introduction 4 1. America at the Vanguard: Democracy Promotion and the Bush Doctrine 16 2. Assessing History’s End: Thymos and the Post-Historic Life 37 3. The Exceptional Nation: Power, Principle and American Foreign Policy 55 4. The “Crisis” of Liberal Modernity: Neoconservatism, Relativism and Republican Virtue 84 5. An “Intoxicating Moment:” The Rise of Democratic Globalism 123 6. The Perfect Storm: September 11 and the coming of the Bush Doctrine 159 Conclusion 199 Bibliography 221 1 Acknowledgements Over the three years I spent researching and writing this thesis, I have received valuable advice and support from a number of individuals and organisations. My supervisors, Peter Field and Jeremy Moses, were exemplary. As my senior supervisor, Peter provided a model of a consummate historian – lively, probing, and passionate about the past. His detailed reading of my work helped to hone the thesis significantly. Peter also allowed me to use his office while he was on sabbatical in 2009. With a library of over six hundred books, the space proved of great use to an aspiring scholar. Jeremy Moses, meanwhile, served as the co-supervisor for this thesis. His research on the connections between liberal internationalist theory and armed intervention provided much stimulus for this study. Our discussions on the present trajectory of American foreign policy reminded me of the continuing pertinence of my dissertation topic. -

Introduction

NOTES Introduction 1. Robert Kagan to George Packer. Cited in Packer’s The Assassin’s Gate: America In Iraq (Faber and Faber, London, 2006): 38. 2. Stefan Halper and Jonathan Clarke, America Alone: The Neoconservatives and the Global Order (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004): 9. 3. Critiques of the war on terror and its origins include Gary Dorrien, Imperial Designs: Neoconservatism and the New Pax Americana (Routledge, New York and London, 2004); Francis Fukuyama, After the Neocons: America At the Crossroads (Profile Books, London, 2006); Ira Chernus, Monsters to Destroy: The Neoconservative War on Terror and Sin (Paradigm Publishers, Boulder, CO and London, 2006); and Jacob Heilbrunn, They Knew They Were Right: The Rise of the Neocons (Doubleday, New York, 2008). 4. A report of the PNAC, Rebuilding America’s Defenses: Strategy, Forces and Resources for a New Century, September 2000: 76. URL: http:// www.newamericancentury.org/RebuildingAmericasDefenses.pdf (15 January 2009). 5. On the first generation on Cold War neoconservatives, which has been covered far more extensively than the second, see Gary Dorrien, The Neoconservative Mind: Politics, Culture and the War of Ideology (Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 1993); Peter Steinfels, The Neoconservatives: The Men Who Are Changing America’s Politics (Simon and Schuster, New York, 1979); Murray Friedman, The Neoconservative Revolution: Jewish Intellectuals and the Shaping of Public Policy (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2005); Murray Friedman ed. Commentary in American Life (Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 2005); Mark Gerson, The Neoconservative Vision: From the Cold War to the Culture Wars (Madison Books, Lanham MD; New York; Oxford, 1997); and Maria Ryan, “Neoconservative Intellectuals and the Limitations of Governing: The Reagan Administration and the Demise of the Cold War,” Comparative American Studies, Vol. -

Australia Muslim Advocacy Network

1. The Australian Muslim Advocacy Network (AMAN) welcomes the opportunity to input to the UN Special Rapporteur on the Freedom of Religion or Belief as he prepares this report on the Impact of Islamophobia/anti-Muslim hatred and discrimination on the right to freedom of thought, conscience religion or belief. 2. We also welcome the opportunity to participate in your Asia-Pacific Consultation and hear from the experiences of a variety of other Muslims organisations. 3. AMAN is a national body that works through law, policy, research and media, to secure the physical and psychological welfare of Australian Muslims. 4. Our objective to create conditions for the safe exercise of our faith and preservation of faith- based identity, both of which are under persistent pressure from vilification, discrimination and disinformation. 5. We are engaged in policy development across hate crime & vilification laws, online safety, disinformation and democracy. Through using a combination of media, law, research, and direct engagement with decision making parties such as government and digital platforms, we are in a constant process of generating and testing constructive proposals. We also test existing civil and criminal laws to push back against the mainstreaming of hate, and examine whether those laws are fit for purpose. Most recently, we are finalising significant research into how anti-Muslim dehumanising discourse operates on Facebook and Twitter, and the assessment framework that could be used to competently and consistently assess hate actors. A. Definitions What is your working definition of anti-Muslim hatred and/or Islamophobia? What are the advantages and potential pitfalls of such definitions? 6. -

Hate by Infected

Infected by Hate: Far-Right Attempts to Leverage Anti-Vaccine Sentiment Dr. Liram Koblentz-Stenzler, Alexander Pack March 2021 Synopsis The purpose of this article is to alert and educate on a new phenomenon that first appeared worldwide in November 2020, as countries started developing COVID-19 vaccination plans. Far-fight extremists, white supremacists in particular, identified pre-existing concerns in the general public regarding the potential vaccines’ effectiveness, safety, and purpose. In an effort to leverage these concerns, the far-right actors have engaged in a targeted campaign to introduce and amplify disinformation about the potential COVID-19 vaccines via online platforms. These campaigns have utilized five main themes. First, content increasing chaos and promoting accelerationism. Second, content to improve recruitment and radicalization. Third, content connecting COVID-19 or the proposed vaccines to pre-existing conspiracies in the movement. Fourth, content fostering anti-minority sentiment. Fifth, they have begun producing content advocating individual- initiative (lone wolf) attacks against COVID-19 manufacturers. Authorities must be cognizant of this phenomenon and think of ways to prevent it. Failure to recognize and appropriately respond may result in increased recruitment and mobilization within the far-right movement. Similarly, failure to curtail this type of rhetoric will likely increase the public’s hesitancy to go and be vaccinated, increasing the difficulty of eradicating COVID-19. Additionally, far-right extremists are likely to continue suggesting that COVID-19 vaccines are part of a larger conspiracy in order to persuade potential supporters to engage in individual-initiative (lone wolf) attacks. As a result, COVID-19 vaccine manufacturers and distribution venues are likely to be potential targets. -

“Democratic Self-Government Or Mass Migration? Choose!” by John Fonte, Ph.D., Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute, Washington, DC, USA

“Democratic Self-Government or Mass Migration? Choose!” By John Fonte, Ph.D., Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute, Washington, DC, USA. If Migration is the biggest Challenge of our Time---the key Issue is Who will decide this challenge? There are three possibilities: Supranational institutions (let’s call this Davos); the migrants themselves arriving without the consent of the people in the nations that are affected--or the demos, the citizens of democratic nation-states? Whether migration is decided by Davos, by the migrants or by the Demos will determine the direction of the West in the 21st century. The Challenge of Migration is at the heart of the most important question in politics going back to Plato and Aristotle. Who Governs? Supranational institutions or democratic nation- states? Transnational elites—unaccountable--to any democratic people or the citizens of a nation? The President of the United States, Donald Trump, has described the coming conflict as one between patriotism and globalism. Today, sovereign self-government is challenged within the democratic world and within the West by the ideological and material forces of Transnational or Global Progressivism. The Party of Davos-Global Governance-Transnational Progressivism is supported by an interlocking network of transnational elites including international lawyers, judges, bureaucrats, and activists housed at institutions like the United Nations, the European Commission, the European Court of Human Rights, leading global corporations, NGOs, and within the governments of many Western nation-states. These groups have a symbiotic relationship. John Bolton has referred to some of their practitioners as the “High-Minded.” This network promotes two complimentary ideologies: supranationalism abroad and multiculturalism at home. -

Open Dissertation Draft Revised Final.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School ICT AND STEM EDUCATION AT THE COLONIAL BORDER: A POSTCOLONIAL COMPUTING PERSPECTIVE OF INDIGENOUS CULTURAL INTEGRATION INTO ICT AND STEM OUTREACH IN BRITISH COLUMBIA A Dissertation in Information Sciences and Technology by Richard Canevez © 2020 Richard Canevez Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2020 ii The dissertation of Richard Canevez was reviewed and approved by the following: Carleen Maitland Associate Professor of Information Sciences and Technology Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Daniel Susser Assistant Professor of Information Sciences and Technology and Philosophy Lynette (Kvasny) Yarger Associate Professor of Information Sciences and Technology Craig Campbell Assistant Teaching Professor of Education (Lifelong Learning and Adult Education) Mary Beth Rosson Professor of Information Sciences and Technology Director of Graduate Programs iii ABSTRACT Information and communication technologies (ICTs) have achieved a global reach, particularly in social groups within the ‘Global North,’ such as those within the province of British Columbia (BC), Canada. It has produced the need for a computing workforce, and increasingly, diversity is becoming an integral aspect of that workforce. Today, educational outreach programs with ICT components that are extending education to Indigenous communities in BC are charting a new direction in crossing the cultural barrier in education by tailoring their curricula to distinct Indigenous cultures, commonly within broader science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) initiatives. These efforts require examination, as they integrate Indigenous cultural material and guidance into what has been a largely Euro-Western-centric domain of education. Postcolonial computing theory provides a lens through which this integration can be investigated, connecting technological development and education disciplines within the parallel goals of cross-cultural, cross-colonial humanitarian development. -

Decolonizing Education with Anishinaabe Arcs: Generative STEM As a Path to Indigenous Futurity

Education Tech Research Dev (2020) 68:1569–1593 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-019-09728-6 CULTURAL AND REGIONAL PERSPECTIVES Decolonizing education with Anishinaabe arcs: generative STEM as a path to indigenous futurity Ron Eglash1 · Michael Lachney2 · William Babbitt3 · Audrey Bennett4 · Martin Reinhardt5 · James Davis3 Published online: 19 December 2019 © Association for Educational Communications and Technology 2019 Abstract This paper introduces a generative framework in which translations of Indigenous knowl- edge systems can expand student agency in science, technology, engineering, and math- ematics (STEM). Students move from computer simulations to physical renderings, to repurposing STEM innovation and discovery in the service of Indigenous community development. We begin with the math and computing ideas in traditional Anishinaabe arcs; describe their translation into software and physical rendering techniques, and fnally their workshop implementation with a mix of Native and non-Native students. Quantitative and qualitative analyses of pre-survey and post-survey data indicate increases in students’ understanding of Indigenous knowledge, their creative ability to utilize it in moving from algorithmic to physical designs, and their visions for new hybrid forms of Indigenous futu- rity. We use these fndings to argue that culture-based education needs to shift from a vin- dicationist mode of admiring ancient achievements, to one that highlights students’ agency in a generative relationship with cultural knowledge. Keywords STEM education · Native American · Indigenous knowledge · Educational technology · Design agency Introduction While culturally responsive education has been a promising trend, it is also a tricky path to navigate. Take, for example, ethnomathematics, which endeavors to “translate” between Indigenous math concepts and their Western equivalents.