Early Marriage in Taiwan: Evidence from Panel Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Origins of Cultural Norms: the Case of Animal Husbandry and Bastardy

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 10969 Economic Origins of Cultural Norms: The Case of Animal Husbandry and Bastardy Christoph Eder Martin Halla AUGUST 2017 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 10969 Economic Origins of Cultural Norms: The Case of Animal Husbandry and Bastardy Christoph Eder University of Innsbruck Martin Halla University of Innsbruck, CD-Lab Aging, Health and the Labor Market, IZA and GÖG AUGUST 2017 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 10969 AUGUST 2017 ABSTRACT Economic Origins of Cultural Norms: The Case of Animal Husbandry and Bastardy* This paper explores the historical origins of the cultural norm regarding illegitimacy (formerly known as bastardy). -

Shotgun Wedding by Tiffany Zehnal

Shotgun Wedding by Tiffany Zehnal Writer's First Draft May 22, 2006 FADE IN: EXT. A SMALL TEXAS TOWN - EARLY MORNING The kind of town where people get by and then die. The morning sun has no choice but to come up over the horizon. A SQUIRREL... scurries across a telephone line... down a pole... over a "DON'T MESS WITH TEXASS" sticker... into an apartment complex parking lot... EXT. SHERWOOD FOREST APARTMENT COMPLEX ...and under a BLACK EXTENDED CAB PICK-UP TRUCK that faces out of its parking spot. It's filthy. As evident by the dirt graffiti: "F'ing Wash Me!" The driver's side mirror hangs by a metal thread. On the windshield, ONE DEAD GOLDFISH, eyes wide open... ...and in the back window, an EMPTY GUN RACK. INT. BATHROOM A box of AMMUNITION. A pair of female hands with a perfect FRENCH MANICURE loads bullets into a SHOTGUN. One by one. The only jewelry, a THIN, SILVER BAND on the middle finger of her left hand. INT. BEDROOM A clock radio -- the numbers flip from 5:59 to 6:00. COUNTRY MUSIC fills the room as a hand reaches over and HITS the snooze button. A millisecond of silence. An OFF-SCREEN SHOTGUN IS COCKED. The mound in the middle of the bed lifts his eye mask. This is WYATT, 34, handsome in a ruggedly casual never-washes-his- jeans way. He has a SMALL MOLE on his neck which, if you squint, looks like Texas. Wyatt’s all about maintaining the status quo. If he used words like status quo. -

Download Marriages, Families, and Relationships Making Choices

MARRIAGES, FAMILIES, AND RELATIONSHIPS MAKING CHOICES IN A DIVERSE SOCIETY 13TH EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Mary Ann Lamanna | --- | --- | --- | 9781337109666 | --- | --- Families: Forms of Family Diversity While income averaging might still benefit a married couple with a stay-at-home spouse, such averaging would cause a married couple with roughly equal personal incomes to pay more total tax than they would as two single persons. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, pp. The European Convention and Relationships Making Choices in a Diverse Society 13th edition the Legal Status of Children Born out of Wedlock protects the rights of children born to unmarried parents. These "unclear families" do not fit the mould of the monogamous nuclear family. Polygynyor men having multiple wives at once, is one of the most common marital arrangements represented in the Hebrew Bible; [] another is that of concubinage pilegesh which was often arranged by a man and a woman who generally enjoyed the Families rights as a full legal wife other means of concubinage can be seen in Judges where mass marriage by abduction was practiced as a form of punishment on transgressors. Archived from the original on 9 November Narrative updates incorporate the latest scholarship. Family Life in the Age of Shakespeare. Man, New Series. The matrilineal Mosuo of China practice what they call "walking marriage". A civil unionalso referred to as a civil partnershipis a legally recognized form of partnership similar to marriage. Royal Anthropological Institute. This edition features Families new question-driven narrative, Families chapters devoted to the lives of ordinary people that make the past real and relevant, and the best and latest scholarship throughout. -

Marriage Annulment - the Need for Legislation

University of Miami Law Review Volume 24 Number 1 Article 7 10-1-1969 Marriage Annulment - The Need for Legislation Beverly A. Rowan Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr Recommended Citation Beverly A. Rowan, Marriage Annulment - The Need for Legislation, 24 U. Miami L. Rev. 112 (1969) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol24/iss1/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARRIAGE ANNULMENT-THE NEED FOR LEGISLATION BEVERLY A. ROWAN* I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................... 112 II. JUSTIFICATION FOR THE ACTION .......................................... 114 III. THE FLORIDA POSITION .................................................. 114 IV. THE VOID-VOIDABLE DISTINCTION .......................................... 116 V . GROUNDS ................................................................ 118 A . Incest ............................................................... 118 B . Bigamy ............................................................. 119 C . Im potency .......................................................... 120 D. M ental Incompetency ................................................ 121 E. Intoxication or Influence of Drugs ................................... -

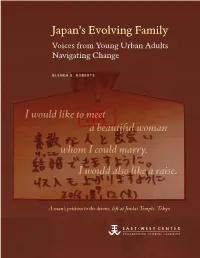

Japan's Evolving Family

Japan’s Evolving Family: Voices from Young Urban Adults Navigating Change Navigating Adults Urban Young from Voices Family: Evolving Japan’s Japan’s Evolving Family Voices from Young Urban Adults Navigating Change GLENDA S. ROBERTS I would like to meet a beautiful woman whom I could marry. I would also like a raise. A man’s petition to the divine, left at Jindai Temple, Tokyo Roberts East-West Center East-West Japan’s Evolving Family: Voices from Young Urban Adults Navigating Change GLENDA S. ROBERTS The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the Pacific through cooperative study, research, and dialogue. Established by the US Congress in 1960, the Center serves as a resource for information and analysis on critical issues of common concern, bringing people together to exchange views, build expertise, and develop policy options. The Center’s 21-acre Honolulu campus, adjacent to the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, is located midway between Asia and the US mainland and features research, residential, and international conference facilities. The Center’s Washington, DC, office focuses on preparing the United States for an era of growing Asia Pacific prominence. EastWestCenter.org Print copies are available from Amazon.com. Single copies of most titles can be downloaded from the East-West Center website, at EastWestCenter.org. For information, please contact: Publications Office East-West Center 1601 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96848-1601 Tel: 808.944.7145 Fax: 808.944.7376 [email protected] EastWestCenter.org/Publications ISBN 978-0-86638-274-8 (print) and 978-0-86638-275-5 (electronic) © 2016 East-West Center Japan’s Evolving Family: Voices from Young Urban Adults Navigating Change Glenda S. -

Ending Child Marriage in a Generation What Research Is Needed?

Ending Child Marriage in a Generation What Research is Needed? BY MARGARET E. GREENE, PHD Ending Child Marriage in a Generation What Research is Needed? BY MARGARET E. GREENE, PHD January 2014 Contact the author at [email protected] or at www.greeneworks.org Cover: A pregnant 15-year-old with her older husband, who is a migrant worker in Mumbai, India, meet with The Veerni Project. They were wed when she was ten in his village near Jodhpur. ©2006 Rose Reis, Courtesy of Photoshare The Problem of Child Marriage for Girls and for Development Two interrelated reasons form the central rationales for working to end the practice of child marriage: upholding the rights of girls, and achieving health and development goals. Girls’ rights, health and development are undermined by the impact of early marriage, pregnancy and childbearing on their mortality and morbidity, the early termination of their schooling, and the ripples of girls’ poor health and limited human capital on their future productivity and the lives of their children, families and their nations. In the absence of valid consent – which ‘children’ by definition are not able to give – child mar- riage may be understood as a coerced act that violates the human rights of 14.2 million girls who marry as children each year.3 Once girls are married, their status infringes upon a range of their rights. Most child brides are burdened with responsibilities as wives and mothers with little support, resources, or life experience to meet these challenges. Compared to their unmarried peers or to older women, girls who marry before the age of 18 are likely to have lower educational attainment, greater chances of experiencing unwanted pregnancies, and are at greater risk of sexual and reproductive health morbidities and maternal mortali- ty.4 They go into marriage at a disadvantage with regard to their husbands, who tend to be older and to have more experience of school, work and often, previous relationships. -

A Shotgun Wedding Customer Taster

A Sh tgun Wedding A Murder Mystery by Andrew Hull Customer Taster, Extracted from the main pack A Sh tgun Wedding A Murder Mystery Copyright 2013 by Andrew Hull This afternoon, millionaire businessman John Davenport, married his fiancée, Juliet Lightfoot, following a whirlwind romance. The reception is shortly to take place at the Great Bantworthy Golf Club. Family, friends and colleagues have gathered to celebrate the happy occasion, but not everyone wishes John well… COPYRIGHT REGULATIONS This murder mystery is protected under the Copyright laws of the British Commonwealth of Nations and all countries of the Universal Copyright Conventions. All rights, including Stage, Motion Picture, Video, Radio, Television, Public Reading, and Translations into Foreign Languages, are strictly reserved. No part of this publication may lawfully be transmitted, stored in a retrieval system, or reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, manuscript, typescript, recording, including video, or otherwise, without prior consent of Lazy Bee Scripts. A licence, obtainable only from Lazy Bee Scripts, must be acquired for every public or private performance of a script published by Lazy Bee Scripts and the appropriate royalty paid. If extra performances are arranged after a licence has already been issued, it is essential that Lazy Bee Scripts are informed immediately and the appropriate royalty paid, whereupon an amended licence will be issued. The availability of this script does not imply that it is automatically available for private or public performance, and Lazy Bee Scripts reserve the right to refuse to issue a licence to perform, for whatever reason. Therefore a licence should always be obtained before any rehearsals start. -

Is the Male Marriage Premium Due to Selection? the Effect of Shotgun Weddings on the Return to Marriage

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Ginther, Donna; Zavodny, Madeline Working Paper Is the male marriage premium due to selection? The effect of shotgun weddings on the return to marriage Working Paper, No. 97-5a Provided in Cooperation with: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Suggested Citation: Ginther, Donna; Zavodny, Madeline (1998) : Is the male marriage premium due to selection? The effect of shotgun weddings on the return to marriage, Working Paper, No. 97-5a, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Atlanta, GA This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/100753 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die -

Gentle Romances, 2014

ISBN 978-0-8444-9569-9 Gentle 2014 Romances National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped Washington 2014 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Library of Congress. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. Gentle romances, 2014. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 978-0-8444-9569-9 1. Blind--Books and reading--Bibliography--Catalogs. 2. Talking books-- Bibliography--Catalogs. 3. Braille books--Bibliography--Catalogs. 4. Love stories-- Bibliography--Catalogs. 5. Library of Congress. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped--Catalogs. I. Title. Z5347.L533 2014 [HV1721] 016.823’08508--dc23 2014037860 Contents Introduction .......................................... iii pense, or paranormal events may be present, Audio ..................................................... 1 but the focus is on the relationship. Dull, Braille .................................................... 41 everyday problems tend to be glossed over Index ...................................................... 53 and, although danger may be imminent, the Audio by author .................................. 53 environment is safe for the main characters. Audio by title ...................................... 61 Much of modern fiction—romances in- Braille by author ................................. 71 cluded—contains strong language and Braille by title ..................................... 73 descriptions of sex and violence. But not Order Forms ........................................ -

Crown Him Week 3 “Shotgun Wedding” November 22, 2020 Frank Burns Mdiv Remnant Church of Sarasota

Crown Him Week 3 “Shotgun Wedding” November 22, 2020 Frank Burns MDiv Remnant Church of Sarasota Shotgun Wedding I really love weddings. PHOTO 1 It never really dawned on me when I became a pastor that I would be invited to participate in them. They really are wonderful moments if they are centered on Christ. I only perform weddings between two believers who I know are fully committed to Christ. I love that God came up with the idea of the Covenant of Marriage and used that image to describe our salvation. There is something holy about two people, a man and woman, locking eyes and declaring their love for each other and then together their love for Jesus. They tell each other, I could have chosen anyone, but I choose you because God has chosen us. It is really a beautiful thing. Unless.... Well in Texas we have these things called Shotgun Weddings. PHOTO 2 They are not about free will, they are about survival. Usually the Father of the Bride is the one packing heat and the Groom to be is the one feeling it and sweating. The marriage vows are not really beautiful at all because everyone knows that boy had no choice. The audience knows it, the Father of the Bride knows it, the Groom knows it....and most sadly...the Bride knows it. Declaration of Love made under duress, without free will, is not love at all. Throughout scripture, Jesus is illustrated for us as a Bridegroom coming for His Bride. This is no accident or coincidence. -

Bringing Back the Shotgun Wedding

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (Sociology) Penn Sociology 1988 Bringing Back the Shotgun Wedding Frank F. Furstenberg University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/sociology_papers Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons Recommended Citation Furstenberg, Frank. 1988. "Bringing Back the Shotgun Wedding." The Public Interest 90 121-127. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/sociology_papers/12 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bringing Back the Shotgun Wedding Disciplines Family, Life Course, and Society | Sociology This journal article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/sociology_papers/12 CONTR 0 VERS Y BringingBack the Shotgun Wedding FRANK F. FURSTENBERG, JR. ACKthoughtIN THthatE lateteenage1950s,parenthoodat the peakwasoaf problemthe baby inboothim,s eounnotry.one To be sure, lots of adoleseents had babies--even more than do today-- but almost all were married before or shortly after the pregnancy oe- eurred. As some family sociologists observed at the time, pregnancy was often part of the eourtship proeess, propelling many young eou- ples into marriage at an aeeelerated paee. Women risked their reputa- tions when they eonsented to have sex. If they were unlueky enough to get pregnant, their boyfriends were expeeted to do the honorable thing--whieh they usually did, whether willingly or reluetantly. As many as half of all teenage brides in the late 1950s were preg- nant when they took their wedding vows. Sinee nearly half of all women were married by twenty, almost one woman in four started her family as a pregnant teenager. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Radboud Repository PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/62933 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2017-12-06 and may be subject to change. Do Opposites Attract Divorce? Dimensions of Mixed Marriage and the Risk of Divorce in the Netherlands Do Opposites Attract Divorce? Dimensions of Mixed Marriage and the Risk of Divorce in the Netherlands Trekken tegenpolen echtscheiding aan? Dimensies van gemengd huwen en de kans op echtscheiding in Nederland Een wetenschappelijke proeve op het gebied van de Sociale Wetenschappen Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen, volgens besluit van het College van Decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 31 januari 2002 des namiddags om 3.30 uur precies door Jacobus Petrus Gerardus Janssen geboren op 22 augustus 1972 te Zeist Promotores: Prof. Dr. W.C. Ultee Prof. Dr. M. Kalmijn - Katholieke Universiteit Brabant (Tilburg University) Co-promotor: Dr. P.M. de Graaf Manuscriptcommissie: Prof. Dr. N.D. de Graaf Prof. Dr. M. Wagner - Universität zu Köln, Cologne, Germany Prof. Dr. J. Dronkers - European University Institute, San Domenico di Fiesole, Firenze, Italy © J.P.G. Janssen 2001 ISBN: 90 5170 576 X The research reported in this book was supported by the Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NWO), Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research, project number 510-05-0603.